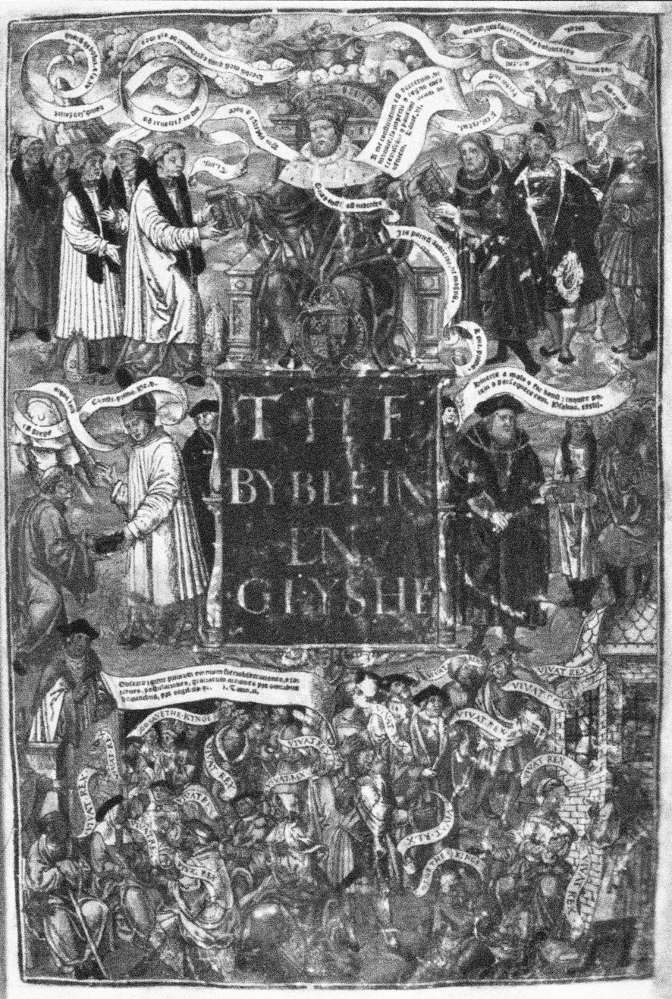

Henry VIII has spent nearly five centuries hiding behind the skirts of his many wives. He is one of the most notorious Kings of England, once hailed the greatest Prince in Christendom, he was revered, then reviled, and now we seek to rehabilitate him.

Henry VIII has spent nearly five centuries hiding behind the skirts of his many wives. He is one of the most notorious Kings of England, once hailed the greatest Prince in Christendom, he was revered, then reviled, and now we seek to rehabilitate him.

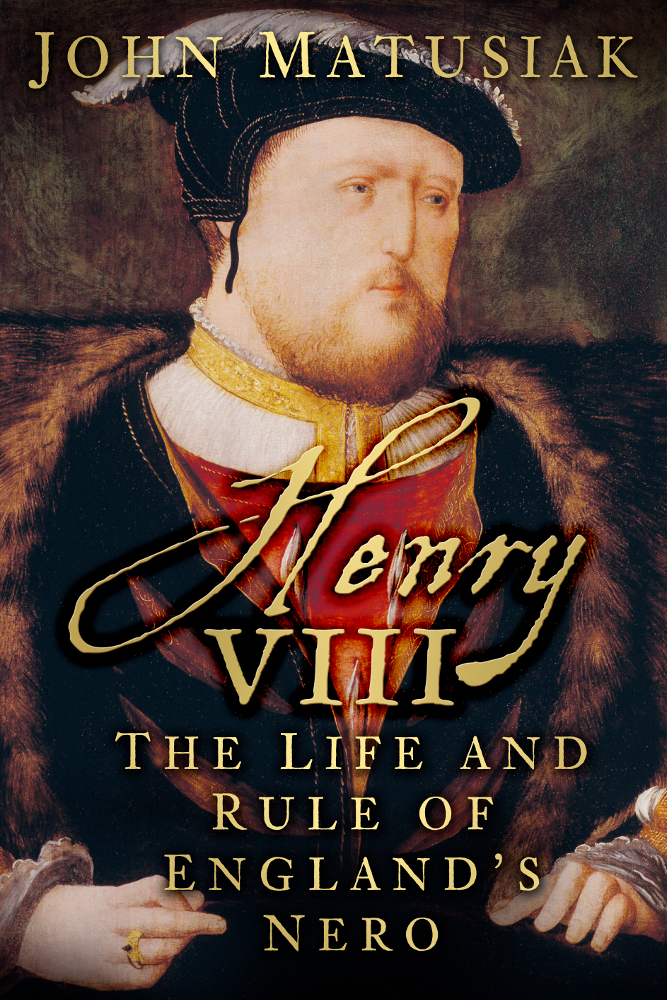

The controversial and challenging Henry VIII The Life and Rule of England’s Nero shatters the myth of the virtuous Prince whose all-consuming quest for an heir tore his kingdom asunder, it paints a vivid picture of the egomaniacal tyrant who condemned himself to failure.

Historian John Matusiak joined us to discuss why Henry VIII was a bad man, and a bad ruler.

This is a fresh look at Henry VIII. Rather than focus on his wives and members of the privy chamber you give us a detailed look at his reign through his politics, and the impact on the common people as well as the nobles. This gives us a realistic picture of the political climate at the time, and the unrest he caused with some of his earlier taxes to fund his wars. He was not in fact always “Bluff King Hal” to his people, was he?

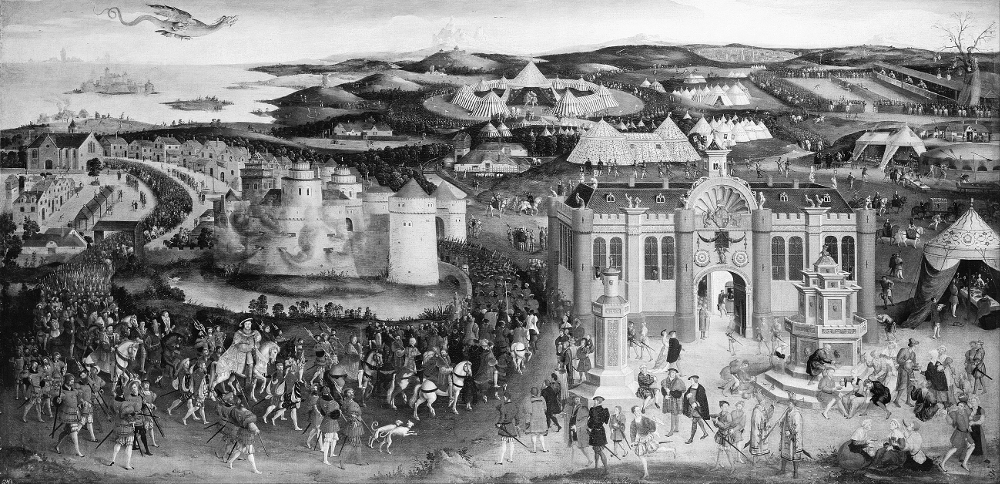

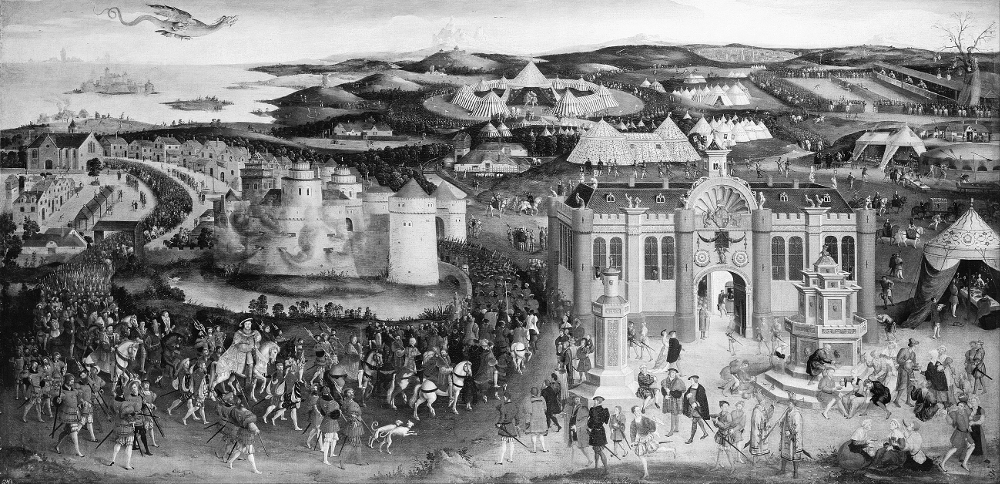

There’s little doubt that Henry VIII, like many exhibitionists, was capable of a certain high-spirited, perhaps even manic, affability, which might pass for ‘charm’ to the sufficiently undiscerning. To say that he enjoyed the limelight is, of course, an understatement and, in his more benevolent moods, he exhibited a certain winning informality that distinguished him markedly from his father. Whether at tournaments or at court revels, in the company of his minions or under the gaze of the common people, he could be guaranteed to perform. Indeed, it was this hearty, back-slapping effervescence – suitably ‘spun’ and exploited by the likes of Thomas Wolsey – that gave rise to what was, arguably, one of the first personality cults of its kind.

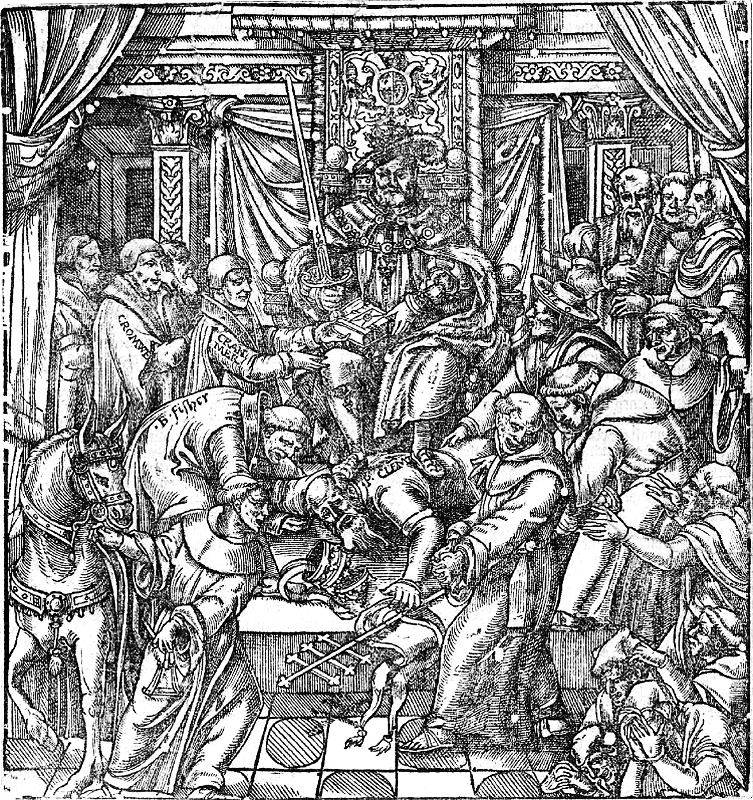

But beneath the colour and panache there was a darker side – darker even than the excesses that are commonly acknowledged these days. Most of us are aware of the fate of Thomas More and John Fisher, but fewer, I suspect, know the full details of the imprisonment and slaughter of the London Carthusians who resisted the imposition of the royal supremacy. During their confinement in a stinking dungeon at Newgate Jail over seventeen days, Humphrey Middlemore, William Exmew and Sebastian Newdigate were chained to posts, loaded with lead, prevented from sitting and ‘never loosed for any natural necessity’ before being hung, drawn and quartered at Tyburn. Their prior, John Houghton, had suffered a similar execution earlier in the month, after which one of his arms was nailed to the door of the London Charterhouse as a gory reminder to the monks inside of what they, too, could expect.

I could extend the list of victims to some considerable length, in fact, but perhaps the somewhat less drastic example of John Wyot, a humble carpenter from Essex, may suffice to prove the point. Not only was Wyot set in a pillory for bad-mouthing the king, but one of his ears was nailed to a board behind his head as punishment for his ‘lewd words’. This, however, was not the limit of his punishment, for he was left in this position with a dunce’s hat upon his head until he demonstrated his remorse and gained his freedom by severing the attached ear.

‘Bluff King Hal’? Does this answer the question?

You observed Henry VII’s neglect to secure a dynastic marriage for his second son, unlike his other three children who were all set to occupy a throne in one way or another. Do you think Henry VIII may have felt the impact of being the “spare heir” and less important than his older brother, and even his sisters at that point?

It’s hard, if not impossible, to read a child’s mind, particularly at a distance of five centuries, of course, but it’s difficult not to draw some obvious conclusions on this one – especially when we take into account what we know about Henry’s personality, both as a child and as an adult. His competitive streak and driving need for self-affirmation are extensively documented, and although there is no mention in the sources of any outright jealousy towards his older brother in particular, one should never assume that absence of evidence is evidence of absence.

The really significant issue, however, may well be that Henry was the ‘spare heir’ not only politically, but emotionally, too. There is much to suggest that Henry VII doted on Prince Arthur, while finding his younger son an infuriating liability. The Spanish ambassador, Gomez de Fuensalidia, tells us, for instance, how Prince Henry’s defiance could drive his father into pathological rages, which left him in a trancelike state, ‘his eyes closed, neither sleeping nor waking’. On one such occasion, it seems, the king fought so violently with his son ‘as if to kill him’. In spite of recent suggestions that young Henry enjoyed a particularly close bond with his mother, there is also evidence that she, too, may have favoured Arthur, just, indeed, as Henry’s elder sister, Margaret, seems to have done.

Despite his conceit, Henry seemed to constantly seek approval from those he considered his betters or perhaps equals, such as his quest for a title from the Pope and his hero-worship of Philip of Castile, and his envy of Francis I. Do you think this feeling of being the “unimportant child” may have had an effect on his confidence as an adult?

This, strictly speaking, is again very much one for the psychologists. But it is a fascinating question, nevertheless, and begs an answer. For what it’s worth, my guess is that Henry did indeed suffer from a heavily suppressed sense of inadequacy and that this would certainly not have been helped by his childhood experiences. The problem, however, was that he remained a child emotionally, arguably until the day he died. It was Sir Geoffrey Elton who may well have captured the essence of the man by describing him as ‘a bit of a baby’. My own feeling is that he probably had something of a ‘love-hate’ relationship with himself – the second aspect of that dichotomy only surfacing in his most private and bleaker moments, of which there certainly a few. Like many an apparently masterful egotist, Henry was laden with anxieties, doubts and insecurities – none of which could be faced head-on, let alone admitted. Beneath many a bad man lies a sad man, one feels, and Henry was ‘sad’ in the broader meaning of the term, too – an individual who, in spite of his desperate need for adulation, never quite ‘had what it takes’, either as a warrior, a lover or, for that matter, a ruler.

Henry has gained a reputation of being malleable, easily influenced and controlled by others, perhaps because there was always a convenient scapegoat to blame when things went awry, but is this really the case?

Henry was frequently naïve, painfully so, but stupid he was not, and given the inherent dangers involved in attempting to make him do what he did not want, it’s unlikely that he was controlled or manipulated in quite the way that some historians have suggested. The broad direction of policy was almost always I think determined by the king – even when it came to the breach with Rome, for instance. As such, he enjoyed what J. J. Scarisbrick termed a ‘commanding partnership’ with his ministers, though the detail for executing his wishes was theirs – not least of all, because Henry’s powers of concentration and application were decidedly limited for much of the time. The best his advisers could achieve was what might be termed a species of ‘deferential manipulation’ or, in other words, persuading him to adapt his approach within the strict parameters that he had already laid down in stone. Wolsey, for instance, seems to have been particularly adept at this; Cromwell, ultimately, less so, which explains his particularly sudden fall from grace. Wolsey met his fate, because he could not deliver; Cromwell, because he genuinely seems to have been moving ahead of the king in ways that Henry was not prepared to tolerate.

Henry took any criticism, not to mention rebellion, from the populace to heart, dealing out savage and abhorrent punishments, even to women. Why did he take any disapproval from the “rude commons” so personally?

Fear, primarily – with perhaps a dash of paternalistic contempt thrown in. He was undoubtedly all too keenly aware of the threat posed by the ‘many-headed monster’ of rebellion. His father, after all, had left him in no doubt of this by his response to the Cornish rebellion in 1497 – something of which the young prince had direct experience when taking shelter from the advancing insurgents with his mother in the Tower of London. And the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536 clearly confirmed just how fragile the forces at his disposal for imposing law and order actually were – something harrowingly reinforced by events in Germany at the time of the Peasants’ War. It was an axiom of contemporary government – and certainly not one invented by Henry – that royal authority must never be compromised.

When it came to more general criticism, however, Henry had little choice in some instances than to suffer in comparative silence. The opposition to Anne Boleyn – particularly as it manifested itself at her coronation – is a very good case in point. There were times, likewise, when he would have to cope with criticism, merely by passing the buck and then bowing to the public opinion. His excruciating surrender over the Amicable Grant is a classic demonstration of this. ‘Well’, he declared after his realm had teetered on the brink of meltdown, ‘some have informed me that my realm was never so rich and that men would pay at the first request, but now I find all the contrary.’ ‘I will no more of this trouble’, he then continued, as if dealing with little more than a playground squabble: ‘Let letters be sent to all shires that the matter be no more spoken of. I will pardon all . . .’

Henry publicly lamented the deaths of Wolsey and Cromwell, conveniently blaming his other advisors for their downfall. Do you think Henry ever saw his impulsive, terrible decisions as a flaw in himself or was his self-deception too far gone?

There is no recorded hint of genuine guilt or prolonged soul-searching that I have come across. On the contrary, Henry’s response was typified by self-pity and irritation that the replacements he selected were either not up to scratch or had forced him into action that he had never wanted in the first place. Indeed, whenever he lamented the deaths of Wolsey and Cromwell, he did so with a view to demeaning their successors. He was, of course, always capable of a rather cloying sentimentality, which passed as quickly as it descended and should not be allowed to fool us. Cromwell, especially, was always intrinsically an object of contempt for Henry, it seems. It was widely rumoured at court, for instance, that ‘the king beknaveth him twice a week, and sometimes knocks him well about the pate’. Likewise, in May 1538 Henry described him to the French ambassador as ‘a good household manager, but not fit to meddle in the affairs of kings’. Above all, there remained a grubbiness about Cromwell that was not confined to his social origins, for Henry suffered at times from delusions of morality and at such times his right-hand man seemed less than appetising.

You pointed out that Anne of Cleves was so quick to accept Henry’s request for an annulment that he was more than a little hurt by this, rather than relieved, and his anguish when he learned of the betrayal of Catherine Howard was quite shocking. Do you think that his delusions were beginning to crack at this point and he could no longer envision himself as the handsome, chivalrous knight he once believed himself to be?

With the onset of chronically declining health in his mid-forties, it’s hard to believe that some semblance of cold reality did not begin to dawn upon the king. It had been clear from the time of Jane Seymour’s death onwards that time was ‘coming fast on’ for him, and it was no small irony that the burgeoning population growth of the sixteenth century meant that at least half his subjects were now under the age of eighteen. The court, in particular, teemed with youngsters, and the celebration of youth, vitality, tourneying, hunting, glorious warfare and, for that matter, vigorous impregnation will have been particularly hard to bear for any sickly has-been. Certainly, his eventual marriage to Catherine Parr suggested a re-ordering of his priorities and tacit acceptance of the inevitable. And yet even in old age, Henry still harboured curious delusions about military glory. By 1540, he was described as possessing ‘a body and a half, very abdominous and unwieldy with fat’. Likewise, the tilt armour manufactured for him at Greenwich in the same year measured fifty-seven inches across the chest. But none of this would prevent him dragging his ailing bulk over to France in a specially constructed litter in quest of ‘knightly virtue’ and ‘glory’.

You chose not to pinpoint a particular time or event when Henry “changed”, rather we saw a gradual increase in Henry’s totalitarianism. In the last decade of his reign his cruelty intensified, even his later wives did not escape his odious threats. Do you think that as age crept up on Henry his behaviour was somewhat of an outlet for him, when he was no longer physically the man he wished to be?

One of the most prevalent – and, I think, pernicious – modern-day myths about Henry VIII is that he was actually two distinct men: the ‘virtuous prince’ of youth and the ‘model tyrant’ of later years. Age, and the disillusionment which invariably accompanies it in the case of a man like Henry, may well have sharpened some of the more unwholesome features of his personality, but time alone did not create the ‘monster’ within him. The egotism, excitability, wilfulness and volatility were all present from an early age, as was the capacity for ruthlessness. As Prince of Wales, for instance, Henry seems to have been a distinct cause of unease to his father who almost certainly developed certain ominous inklings about his personality. Nor should we forget his treatment of Edmund Pole and Empson and Dudley at the very outset of his reign. Even Thomas More, for that matter, betrayed certain forebodings. When More was glorifying at full tilt at the time of the coronation, for instance, he readily acknowledged of Henry that ‘if my head could win him a castle in France … it should not fail to go’.

You observe that in the botched handling of Henry’s will he was refusing to acknowledge the inevitable, his serious decline in health and his looming death. Do you think he regretted leaving the Succession, as it was, to a minor with no council firmly in place, always a serious risk in those times?

The failure to secure the succession effectively may well be single biggest indictment of Henry’s day-to-day incompetence as a ruler and inadequacy as a man. His will’s provisions could not have been more casually considered or generally ill-conceived – and all this in connection with that ‘most precious jewel of a son’ that he had sought so passionately and at such a cost to others. The will, of course, was not even signed, and as a result of Henry’s shameful insouciance, the nine-year-old Edward VI would be cast adrift amid the surging sectarian and faction-ridden currents of mid-Tudor politics without any adequate blueprint for addressing the intricacies consequent upon minority government. Why was this? Fear and a stubborn refusal to face facts seem to be the answer. Even during his final days, Henry had, it seems, been ‘loth to hear any mention of his death’. Indeed, at the very time that he called for his will to be drafted, only a month before he finally gave up the ghost, he seems to have been conceiving and indeed prioritising a hare-brained attack upon Scotland in which he himself was to participate. The fact that that the will eventually contained references both to the king’s begetting further children and to the eventuality of his dying overseas says everything, I fear. A man incapable of imagining his own demise is, I suspect, unlikely to be capable of weighing his actions.

Henry is becoming somewhat of a tragic figure these days, with people desperate to find an answer for his behaviour. Only last year there was a campaign for him to be exhumed so they could prove he had a Kell positive blood type, and I have read endless theories on various rare diseases or his supposed brain damage. Why do you think people won’t accept that Henry was entirely responsible for his own actions?

Cynically, one might say that new theories sell books, and one can’t help feeling that a dash of cynicism here may well contain much more than a dash of truth. Certainly, this stuff is regrettably prevalent these days. You mention blood disorders, but riding accidents have also emerged, I understand, as a convenient way of effectively whitewashing the starker facts. There is, of course, this apparent contrast between the youthful and older ‘Henries’, but the contrast is, as I’ve already suggested, an optical illusion – largely caused, I might add, by the extent to which the virtues of the prince and young king were exaggerated by contemporaries and then universally assumed by subsequent generations of historians. In short, knocks on the head and dodgy corpuscles leave me largely unmoved.

You are releasing another book next year on Thomas Wolsey. Can you tell us a little bit about it?

I have long been nothing short of amazed that a satisfactory popular biography of such an important figure has not been forthcoming. In fairness, it’s a daunting task to make all aspects of the man’s achievements and failures accessible to general readers – especially with the complexities of international diplomacy and canon law involved – but I’m very excited by what I’ve produced, and the book should actually be ready for dispatch to my publisher in about three days, at which point I’ll be more than ready to toast the good cardinal with a celebratory pint of Guinness! All being well, publication is likely to be brought forward to March 2014.

Without, I hope, sounding too pretentious, the book is, arguably, the first comprehensive attempt in over thirty years to explore the many contrasting layers of the much-maligned minister`s life and career. I started the biography with no conscious assumptions, and sought to look instead at the ‘real’ person in the cold light of his actions. What emerges, I think, is a man of contradictions and extremes whose meteoric rise was marked by an equally inexorable descent into desperation, as he attempted in vain to satisfy the tempestuous master whose ambition ultimately broke him. Far from being one more familiar portrait of an overweight and overweening spider or another cautionary tale of pride preceding a fall, it’s the story – in a nutshell – of how consummate talent, noble intentions and an eagle eye for the main chance can contrive with the vagaries of power politics to raise an individual to unheard of heights before finally consuming him.

Thanks so much for your time John. Is there anything you would like to add?

It would require another book! Perhaps I should merely take this opportunity to thank both you and your readers for so generously allowing me to hold forth. It’s been a pleasure.

With thanks to The History Press.

Buy Henry VIII: The Life and Rule of England’s Nero, Published by The History Press.

Buy Henry VIII: The Life and Rule of England’s Nero, Published by The History Press.

John Matusiak was born in the East End of London in 1955 and studied at the universities of London and Sussex before embarking upon a teaching career that would span more than thirty years. For a third of that time, Matusiak was Head of the History Department at Colchester Royal Grammar School, which itself had been founded by Henry VIII in 1539. A Tudor specialist, John Matusiak’s historical essays have been widely published and praised; he is a regular contributor to The Historical Review. Other works include a biography of Henry V (published by Routeledge, October 2012). Now retired, John Matusiak lives in Colchester, Essex.

John Matusiak at The History Press