Please note that the historical figure King Richard III will be referred to as ‘Richard III’, and Shakespeare’s character Gloucester/King Richard as ‘Richard’ throughout these articles.

“We (as an audience) inevitably approach the play in a suspicious frame of mind, suspicious of the exaggeration of Richard’s evil, and sceptical as to that moral pattern which the characters in the play, and many of its critics, ascribe to the events it depicts, and so, by extension, to historical process in itself. In this sense a sceptical response to the play as history is more than a cranky adherence to fact as such, or a worry about Tudor propaganda; it may be the recognition of an internal incoherence, and the play itself may draw our attention to this.” Edward Burns1

In this series we have thus far discussed ‘Tudor propaganda’, disability, and Richard’s bond with the audience in The Tragedy of Richard III. In my research I have focused on empathy in the Tragedy, both in the text, looking at Richard as a ‘stranger’, and the empathy Richard elicits from the audience. The text reveals not just empathy, but even an attempt at psychological understanding. But the Tragedy also has strong historical foundations that are often overlooked. The Henriad, the tetralogy which begins with the first part of Henry VI and concludes with the Tragedy, follows the struggle for power between the houses of York and Lancaster. The Tragedy is not only about the historical King Richard III, but the entire court. But when Colly Cibber, in 1699, decided to adapt the Tragedy, he edited it heavily, borrowing a little from Henry VI Part III, and reducing the whole play to only 800 lines, compared to 3718 in the folio text. As a result, several historical figures were lost, like Edward, Margaret, Clarence, and Hastings, and the historical complexity, and thus, the entire narrative, compromised.

This has had a lasting effect. In the 18th century, Cibber’s adaptation would feature the first Romantic era Richard, played by David Garrick. Garrick’s tragic villain would influence performances right up until the 20th century. In the 18th century the culture of ‘sensibility’ was on the rise, a belief in a heightened consciousness of self and others, and heightened emotional responses, which led to audiences sympathising with Richard as they may never have done before. Even though Shakespeare’s text was restored in the 19th century, it was still heavily edited as a star vehicle for Richard, as it is performed now. Laurence Olivier’s seminal, understated, but exceedingly dark performances in the 20th century cast a long shadow, and, in what I would suggest was almost an attempt to outdo, or at least move away from that performance, the later part of the century saw Richard’s disability magnified, with Antony Sher’s memorable performance on crutches leaving a lasting impression. By the 21st century, Richard’s villainy has been ramped up to psychopath; the current obsession with serial killers, violence, gore and harming women informing our views of Shakespeare’s disabled king. Without the true historical context, that is all Richard is, a psychopath. We see Richard rampaging through London on a murder spree, but we don’t know why. In the last article in our Who Was Shakespeare’s King Richard III series I will discuss historical context, and ‘lost’ scenes, and how these reflect the original authorial intent in the Tragedy.

Why is historical context so important in the Tragedy?

Because Shakespeare exaggerated Richard III’s disability, and because of the popular ‘Tudor propaganda’ idea, it is generally thought Shakespeare had no interest in historical accuracy. Shakespeare, in fact, did follow the historical sources available to him closely, only making a few deliberate choices outside of the chronicle histories. The historical events of the Henriad make up the full narrative of the cycle of plays. The loss of historical context in Colly Cibber’s adaptation of the Tragedy led a Romantic audience to focus on Richard and his disability, believing his ‘deformity [instigated] his cruel ambition’.2 They felt empathy for Richard because they thought he could not help himself. This early psychological reading of the play, however, lapsed in the 20th century. Even though Cibber’s adaptation had fallen out of fashion by the latter half of the 19th century, and Shakespeare’s text was restored, the Tragedy’s full four hours were rarely performed. Even Laurence Olivier maintained elements of Cibber’s version, which had incorporated some of Richard’s speeches from Henry VI III. Audiences are now rarely shown the full text of the Tragedy. Even the 2016 Hollow Crown season of Henry VI and Richard III, which wove the plays together successfully, cut the Richard III episode to only two hours.

To understand authorial intent in the Tragedy, it’s important to recognise that Shakespeare was actively interested in using the historical sources available to him. Over the course of my research, I have found that a lack of knowledge of the historical events leads to rather different interpretations of the text. I have come across the suggestion that medieval society had the same sort of ideologies as early modern, particularly towards disability; anachronistic application of philosophical influences; historical events, such as Richard III’s claim his brother was illegitimate, and that Richard III resembled his father the Duke of York, are brushed off as ‘absurd’ and ‘invented’ as part of the Tragedy text; and the alleged Tudor ‘obsession’ with Richard’s body shape, rather than their physiognomical focus on his features. Empirical historical evidence provides the true historical context of the Tragedy. Yet, the main issue remains that audiences rarely see the full story. I will now discuss how the severe editing of the play has changed the concept of evil in the Tragedy.

Nemesis Action

R.G. Moulton’s nineteenth century study Shakespeare as a Dramatic Artist was one of the first significant structural analyses of the Tragedy.3 Moulton proposed a ‘Nemesis Action’, which, in the simplest terms, sees those who glory in the death of an adversary fall victim to the next. Various frameworks have been applied to Nemesis Action before, many focusing on Margaret of Anjou as a prophetess; another often deleted scene is 1.3 in which Margaret appears and curses most of the major characters. Providential readings, that the Tragedy’s events are all an ‘Act of God’, were also very popular in the 19th century. But Nemesis Action can be read in a historical framework, if one takes a historian’s approach to it, by paying attention to where Shakespeare adheres to, and diverts from, historical record. This give us an insight into some of the Tragedy’s commentary, for example, the English court had become corrupted by greed during the Wars of the Roses.

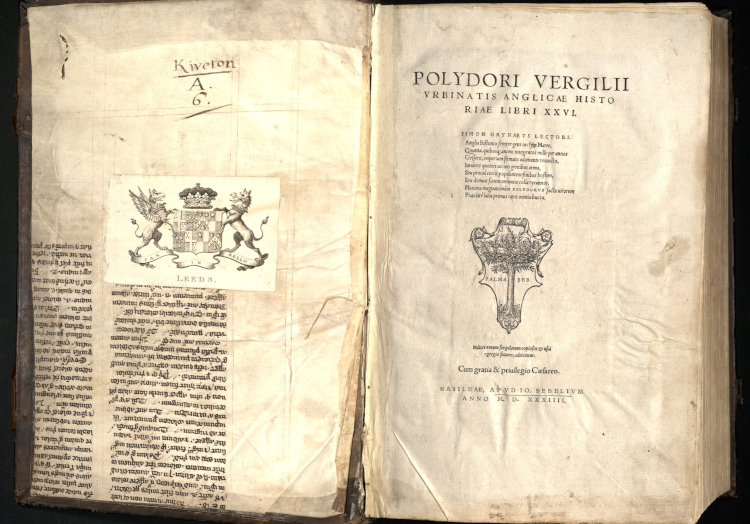

In the Henriad, Richard’s villainous character is ‘created’ in The Third Part of Henry VI, after he murders Henry VI. But prior to that, Richard’s brother, Edmund Earl of Rutland, is murdered by the Lancastrians. Richard’s father, the Duke of York, is then humiliated before his death by Margaret of Anjou, who has dipped a kerchief in the blood of the slain Rutland, and wipes the Duke’s brow with it. Rutland was actually seventeen years of age when he died in battle with his father the Duke of York. The error stating that he was twelve years-old was made by Edward Hall. Hall’s account of Clifford crying ‘thy father slew mine, and so will I do the and all thy kin’4 is uncorroborated, a contemporary letter merely notes the Duke and his son were routed and slain.5 However, Hall’s account may have given Shakespeare the idea to link to the death of Rutland to the deaths of Edward of Lancaster, and later, Richard’s nephews in the Tragedy. In the tetralogy, Rutland is the first innocent slain and Shakespeare takes a completely fictional approach to his death. The first of Richard’s ‘crimes’ in Henry VI III is the killing of Prince Edward of Lancaster, son of Henry VI. Most contemporary accounts say that Prince Edward was killed in the field.6 Most Tudor sources from Vergil onwards claim Edward was killed by George Duke of Clarence, Richard III, Dorset, and Hastings.7 Shakespeare changed this and implicated the three brothers Edward IV, Clarence and Richard. Clearly he was establishing a link between Rutland’s death and Prince Edwards’ death, York revenge on Lancaster, a son for a son. Later, the descent into the destruction of the court begins with the death of two more innocents, Richard’s nephews.

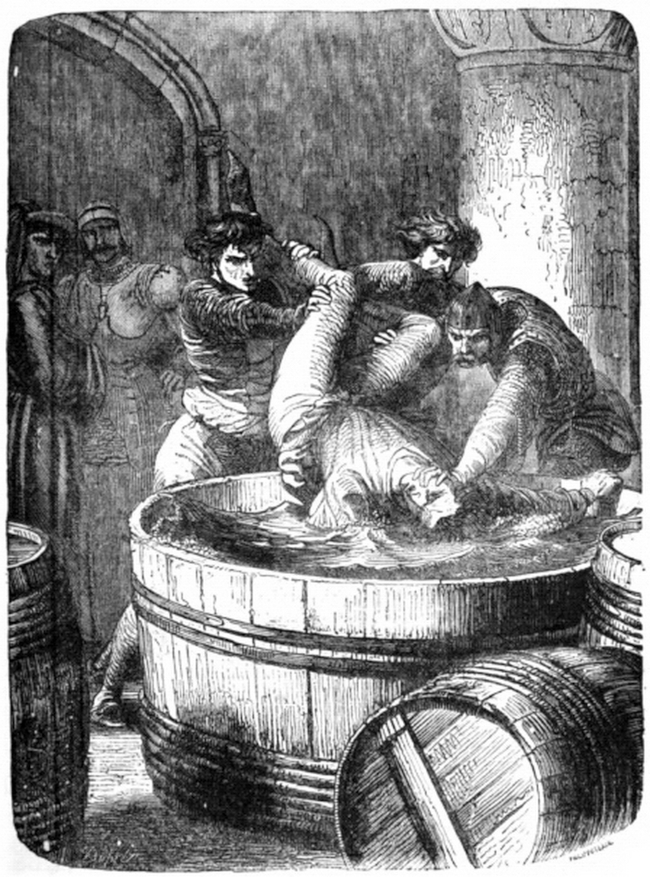

The first victim of Nemesis is the Duke of Clarence, and he is the catalyst for the whole chain of events, an oath-breaker to both Lancaster and York. While Richard orchestrates Clarence’s death by making sure King Edward’s execution orders are not rescinded in time, it was Edward who had imprisoned Clarence in the first place. Thus, after Clarence’s execution, Edward falls victim to Nemesis, dying and leaving the realm in chaos. The Queen and her ‘kindred’, Rivers, Grey and Vaughn are the next victims, for assenting to Clarence’s death. Clarence’s children, Edward and Margaret, appear once in a scene that is always cut from performance. It is a traditional scene of lament, in which Clarence’s children follow Queen Elizabeth, who has just lost her husband. They cry about their own loss, telling Elizabeth “Good aunt, you wept not for our father’s death; How can we aid you with our kindred tears?”. 8 A lot of the choral and lament scenes were cut from the Tragedy because they are a pre-Elizabethan tradition. The fact that we never see this scene means we lose the connection between the Queen’s failure to advocate for mercy for Clarence, and her own tragedies that follow.

Hastings is, of course, the one who exalts in the deaths of Rivers, Grey and Vaughan, and he meets his own death shortly after, the victim of his own pride. Curiously, Shakespeare has Hastings stop to talk to an officer of the court, and boast of his enemies’ deaths, to someone who is beneath him in rank. This questions Hastings’ behaviour as a noble. Buckingham, who had laughed at Hastings’ false sense of security as he goes to the Tower to his death, is next. Shakespeare presents Buckingham as an untrustworthy creature, fully complicit in Richard’s crimes up until his baulking at killing Richard’s nephews. Buckingham even tells Richard that ‘we will plant some other in the throne’,9 indicating that he might betray him. Interestingly, there are contemporary rumours from France accusing Buckingham of killing Richard III’s nephews.10 Hastings and Buckingham are often seen as innocent victims of the historical Richard III, an uncritical opinion based on the idea of a ‘tyrannical’ Richard III, but that sympathy often extends to performance. Even Thomas More was puzzled by Buckingham, commenting on Buckingham turning against Richard ‘he so lightly turned from him and so highly conspired against him, that a man would marvel whereof the change grew.’11 Although Hastings has only a small role, like the queen’s kin, Buckingham has an extensive and complex role in the Tragedy, and the extent of his machinations never being performed in full reduce him to just another of Richard’s ‘victims’.

The murder of Richard’s nephews falls outside of Nemesis Action. They are innocent victims that represent a final obstacle in a terrible ambition. There’s no denying Shakespeare depicted Richard as responsible for their deaths. But, when considering authorial intent, it is important to remember that it was not only Richard who was responsible. In Henry VI, Richard carries out his own murders. Significantly, in the Tragedy, the reason he has others carry out executions and murders is because all of England is implicated in these deaths. This is where Richard’s alleged ‘deformity’ is important. Richard’s shape mirrors a ‘deformed’ body politic, a court so corrupt, so avaricious, that they have created a monster. Richard, of course, is the monster. But all of England is held responsible, from the nobility to the apathetic citizens. As Sir James Tyrrel laments after the murder of Edward IV’s children:

‘The tyrannous and bloody deed is done:

The most arch act of piteous massacre

That ever yet this land was guilty of.’12

True evil in the Tragedy flows not from Richard, but from the history that Richard shares with his peers.

Citizens and Scriveners

Two neglected scenes that are particularly important to the narrative are Act 2, Scene 3, featuring three citizens of London, and Act 3, Scene 6, featuring the Scrivener. They describe London’s social climate at the time of Richard’s takeover in a short space. Unfortunately, they are almost always left out of modern performance. In Act 2, Scene 3, three citizens are discussing the king’s death. The First Citizen announces that 12 year-old Edward will rule after his father’s death, to which the pessimistic Third Citizen opines ‘Woe to that land that’s governed by a child’,13 sparking a debate over Henry VI’s minority reign. The Third Citizen reminds the audience that the two factions, the king’s noblemen and the queen’s kin, are in competition for the young King’s allegiance, that Richard is dangerous, the queen’s brothers and sons ‘haught and proud’, and that England would only prosper if the factions were reigned in, ‘were they to be ruled, and not to rule’.14 While the First Citizen remains doggedly optimistic, the Second Citizen remains somewhere in the middle admitting that the people are worried about the succession.15 The Third Citizen claims the people have an instinct for danger, having seen it before, referring to Henry VI.16 If the audience is unfamiliar with the history of Henry VI’s reign, here they are given a powerful suggestion of the dangers of a minority rule in which noble factions are left to feud unchecked. To a modern audience used to elected governments, Richard’s choice to take the crown from a twelve year-old boy may seem less shocking, even responsible. Transferring thrones to men of age, was, in fact, a common practice in Anglo-Saxon England.

The Scrivener appears in a very brief scene, only fourteen lines make up Act 3 Scene 6, which makes it even more unfortunate that it is often left out. The Scrivener appears on stage alone, showing the audience Hastings’ indictment, which he has written to be announced publicly.

This is the indictment of the good Lord Hastings,

Which in a set hand fairly is engrossed,

That it may be today read o’er in Paul’s.

And mark how well the sequel hangs together:

Eleven hours I have spent to write it over,

For yesternight by Catesby was it sent me;

The precedent was full as long a-doing,

And yet within these five hours Hastings lived,

Untainted, unexamined, free, at liberty.

Here’s a good world the while. Who is so gross

That cannot see this palpable device?

Yet who so bold but says he sees it not?

Bad is the world, and all will come to naught

When such ill dealing must be seen in thought.17

He reveals that he received instructions to write the indictment almost a full day before Hastings was accused of any wrongdoing, and that Hastings was unaccaused and at liberty while the scrivener was writing out the indictment. Who is so stupid, he asks, that can’t see through this deceit, ‘Yet who so bold but says he sees it not?’ He concludes by lamenting evil deeds can only ‘be seen in thought’, and never spoken of. The Scrivener’s scene is generally read as a warning to the audience about the corruption in Richard’s government, in which he describes Hasting’s indictment as pre-fabricated. Yet, Richard has already boasted about his plots, and Hastings’ execution should not be shocking to the audience. I suggest that the Scrivener’s scene is warning the audience of the deceitfulness of the written word, especially the official word of the government. The Tragedy tells us that the government line is untrustworthy, and that the chronicles are flawed. The Scrivener is otherwise irrelevant to the plot, he serves no other purpose than to comment on the ease with which a historical testimony can be falsified.

Did Shakespeare exaggerate Richard III’s crimes?

This question is not overly complicated, Shakespeare did exaggerate some of Richard III’s ‘crimes’. This does not demonstrate, however, any evidence of ‘Tudor propaganda’. All of the crimes Richard carries out in the Tragedy come from historical record, whether the events were thought of as facts, or recorded as rumours. Probably the most exaggerated of Richard’s crimes is his complicity in his brother’s death, George, Duke of Clarence. Shakespeare’s sources, both Vergil and Holinshed mention the ‘prophecy of G’ that Shakespeare utilised. Vergil wrote that ‘A report was even then spread amongst the common people, that the king was afeard, by reason of a soothsayers prophecy[…]after king Edward, should reign someone the first letter of whose name should be G.’18 Holinshed implicated the queen, Elizabeth Wydeville, in this, saying ‘the king and queen were sore troubled’ over it and ‘began to conceive a grievous grudge against this duke, and could not be in quiet till they had brought him to his end’.19 Thomas More places the blame with the queen with a healthy dose of misogyny, claiming ‘as women commonly not of malice but of nature hate them whom their husbands love’.20It is important to note that in the Tragedy, Clarence is imprisoned by Edward, in the first scene, over the alleged prophecy, and Richard has had nothing to do with this. ‘Plots have I laid, inductions dangerous/By drunken prophecies, libels, and dreams’ 21 can be read either way, it is not certain Richard invented the rumour himself. Richard meets Clarence, who is on his way to the Tower, and Richard tells his brother his imprisonment is clearly the fault of the queen. Shakespeare is critical of ‘false, fleeting perjured Clarence’ because of his treachery; historically Clarence rebelled against his brother to join his father-in-law the Earl of Warwick and the Lancastrian faction, before turning on his father-in-law to reconcile with Edward. Yet, Shakespeare also places the blame for his execution with the queen and her kindred, for not advocating for mercy for Clarence. Richard is merely taking advantage of the already-complicated situation. Shakespeare knew of Clarence’s history of treason, and had access to the information about Clarence’s complicity the judicial murder the queen’s father and brother, all recorded in historical chronicles. Shakespeare chose Clarence’s execution, or murder, as it is depicted in the Tragedy, as his catalyst for Nemesis. In the Tragedy, blame for Clarence’s death is shared between the king and queen. Shakespeare was likely influenced by Holinshed’s depiction of the queen, but also Vergil’s criticism of Edward IV’s actions. It is Edward who falls victim to Nemesis next, before the queen’s kindred. The severity of Edward IV ordering his brother’s execution is often glossed over, partly because of our stereotypical views of medieval life as barbaric. But the fratricide clearly felt disturbing to Shakespeare a century onwards.

Of Richard’s other ‘crimes’, Hastings and Buckingham are not presented as innocent victims of Richard, but rather as deserving of their executions. Nor does Shakespeare make much of the deaths of Rivers, Grey and Vaughn, they are dispatched within 23 lines, with Rivers blaming Margaret’s curses. This is more of a choric scene, in which Rivers begs God to have mercy on his sister and her children, reflecting the evils to come, rather than a lament reflecting on their death. The death of Elizabeth’s sons, as we have discussed, is portrayed as a shared responsibility and not solely attributed to Richard.

Perhaps one of Richard’s most famous crimes in the play, second only to the murder of his nephews, is the alleged murder of his wife. The influence the Tragedy has had on the idea of the historical Richard III and Anne Neville’s marriage is complex. This is a significant example of where fiction and history are completely blurred. There is nothing left of the historical Anne Neville, not a scrap of handwriting, only a handful of accounts written about her, even her grave remains lost inside Westminster, her only memorial a plaque organised by the Richard III Society in the 20th century. Because the scene between Anne and Richard in the Tragedy has become somewhat iconic, and because for so long people believed that Richard really was ‘deformed’ and a tyrant, it seems that many believe the Tragedy’s version of events, that Richard ‘tricked’ Anne into marrying him. Of course, it didn’t happen that way historically, and it doesn’t even happen that way in the play. The ‘wooing scene’, as it is known, has no connection to the narrative, which has led some critics to believe it was inserted at a later date, perhaps even as a replacement for the long ‘wooing scene’ where Richard pesters Elizabeth Wydeville for her daughter’s hand.22 And in both scenes, neither woman is fooled by Richard’s antics. Richard, in fact, underestimates them. In the second scene of the Tragedy, Anne’s fury towards Richard softens as he ‘wins’ her, and in performance it is often as a result of Richard’s flattery. But the text reveals that Anne is in control for the entire scene, and isn’t fooled by him for a moment.

Misogyny colours the view of Anne in the Tragedy. Many seem to think that Richard has ‘conquered’ Anne because of her vanity. Richard aims to flatter as he confesses to killing her husband Edward and his father Henry VI because ‘thy heavenly face that set me on’.23 Anne’s religious vanity, perhaps, has been appealed to, seeing Richard as a sinner she can reform. But the significance of the scene is that she has forced Richard to confess to those sins. Once he has done so, and offered his sword up for Anne to slay him with, she declares she will not be his executioner.24 Anne knows that Richard is untrustworthy, she tells him she fears both his heart and tongue are false,25 yet, pragmatically, Richard can offer her protection. Having a historical knowledge of the situation here is useful, Anne was 17 year-old widow who escaped from the clutches of her brother-in-law, the Duke of Clarence, who was attempting to keep her unmarried so he could have her half of the vast Warwick inheritance.26 The historical Anne Neville chose to marry Richard III, and while we have no records of their relationship prior to marriage, we can presume Anne was an active participant in pursuing the marriage, just as Shakespeare’s Anne makes her own decisions. There is no sentence in which Anne had no control over, her speech, while fiery, is deliberate, measured, and when she extracts the confession that she wants from Richard, and confirms her suspicions that he is not to be trusted, she makes her decision to accept him with at least those facts established.

Later Anne laments that her ‘woman’s heart/Grossly grew captive to his honey words’,27 ‘grossly’ meaning ‘foolishly’, and she also reveals she is unable to sleep because of Richard’s nightmares. She speculates that Richard ‘will be rid of me’.28 The rumours that Richard III poisoned his wife appear in chronicles, but poisoning rumours were commonplace, and the presence of them means little. Vergil was evasive, although he suggested that Richard had spread rumours of Anne’s death abroad in the hope that it would drive her to illness, and that after she had confronted him about it, she died shortly after either of ‘sorrow’ or ‘poison’.29 I would suggest, in fact, that Shakespeare depicts Richard driving Anne to her death by exacerbating her sorrow, rather than poisoning her, or the more violent murders we often see in performance and adaptation.

Rumour it abroad

That Anne my wife is very grievous sick.

I will take order for her keeping close.

Inquire me out some mean, poor gentleman,

Whom I will marry straight to Clarence’ daughter.

The boy is foolish, and I fear not him.

Look how thou dream’st! I say again, give out

That Anne my queen is sick and like to die.

About it, for it stands me much upon

To stop all hopes whose growth may damage me.30

In this speech Richard merely indicates he wants to halt anything that will thwart him, which includes marrying off Clarence’s daughter, although he does not see Clarence’s son as a threat. Richard instructs Catesby to read the rumours, and then says he will take responsibility to keep Anne out of sight. There is no indication here that Richard either wants or needs to poison Anne. Anne, in fact, blames herself for cursing Richard, after telling him ‘And when thou wedd’st, let sorrow haunt thy bed’, thinking she had ‘proved the subject of mine own soul’s curse’.31 She is in utter despair, and I suggest Shakespeare hints at a weakened state of health from her depression. Later, when Anne’s ghost appears to taunt Richard, she does not tell us she was murdered. The other ghosts implicate Richard in their murders; Prince Edward of Lancaster: ‘Think how thou stabb’st me in my prime of youth’;32 King Henry VI: When I was mortal, my anointed body/By thee was punchèd full of holes;33 George Duke of Clarence: Poor Clarence, by thy guile betrayed to death.;34, Young King Edward and Prince Richard: Dream on thy cousins [nephews] smothered in the Tower.35 Anne’s ghost says:

Richard, thy wife, that wretched

Anne thy wife,

That never slept a quiet hour with thee,

Now fills thy sleep with perturbations.

Tomorrow in the battle think on me,

And fall thy edgeless sword. Despair and die. 36

In this speech Anne merely tells us she is wretched. She clearly has come to regret her decision, but if anything has truy poisoned her, it is her spirit that has been poisoned by the corruption and machinations of the court. I suggest that Shakespeare does not accuse Richard III of murdering his wife. He depicts Richard as one of the forces driving Anne to illness and death through anguish and anxiety. And this is absolutely a significant difference between text and performance. The choice to have Anne murdered is often made. The last screen adaptation of the Tragedy, in The Hollow Crown, saw Anne set upon by two executioners who beat her to death, thankfully off-screen. But I can only imagine her death will grow even more gruesome in the current age of screen violence.

Conclusion

Sigmund Freud wrote that, after Richard’s opening soliloquy, ‘we feel that we ourselves might become like Richard, that on a small scale, indeed, we are already like him. Richard is an enormous magnification of something we find in ourselves as well.’37 This the is real key to the Tragedy‘s long running success. As Edward Burns writes, that ‘internal incoherence’ is obvious to the audience. All of us have felt misunderstood at some point. We share emotions with Richard throughout the play. The audience never believes absolutely that the real Richard III was this evil, and we wonder what Shakespeare is trying to tell us.

Disappointingly, media violence is starting to dictate performances. Rupert Goold’s 2016 adaptation at the Almeida was put on less than a year after the stately reinterment celebrations for Richard III in the city of Leicester. The play opened with a scene where archeologists were exhuming Richard III’s remains, holding out his curved spine for the audience to see. The open grave remained at the front of the stage for the duration of the play, a glass cover that sliding back as the performance progressed. Richard’s scoliosis is emphasised throughout, with his spine protruding from the shoulder of his armour in the final battle. Ralph Fiennes’ Richard was deeply resentful about his disability and the treatment he receives, that’s nothing new. What struck me as ‘new’ about this play is the emphasis on visible disability and the connection between disability and sexual violence. When when wooing Lady Anne, Richard grabs her genitals and slaps her face, and later rapes Elizabeth Wydeville when seeking her daughters hand. It is a cheap and exploitative trick, that is absolutely and entirely removed from Shakespeare’s text.

Shakespeare himself has been the target of bad press, with conspiracy theories about authorship and classist attempts to diminish his talent by claiming he was a ‘money-grabber’ uninterested in the quality of his work. The influence of this sort of nonsense has made it easier to believe that Shakespeare was writing a play to flatter his monarch, or even to degrade disabled people. But all of the Tragedy’s secrets can be revealed with just a little more attention to the text, and thinking about the narrative in its historical context. Ricardians are always interested in defending Richard III from Shakespeare. But I have found myself defending the Tragedy. Perhaps, instead of dragging Shakespeare’s Richard down with degrading 21st century sensibilities, we need to go back to treating the Tragedy as a historical play. It’s not a crime drama, it is, in fact, a political one, and a social one. It not only examines the government’s responsibility towards its citizens, it examines the citizens responsibility to family, and faith, over allegiance to the government. Richard is not a serial killer, he is a man damaged by trauma, corrupted by his environment, an outsider who falls victim to his own rage. There can be no true appreciation of the Tragedy when it is stripped down to nothing but violence. We need to return to the whole text, the warnings that Shakespeare gives us, that violence begets violence, that greed is destructive, that historical record is untrustworthy, and that truth is subjective and must always be questioned.

We use the Norton Critical Editions of Shakespeare’s texts.

Who Was Shakespeare’s King Richard III? series:

Part One: The Tudor Propaganda Myth

Part Two: The Tragedy and Disability

- E. Burns, Richard III: Writers and Their Work, (Devon: Northcote House Publishing, 2006) 42. ↩

- E. Montagu, An Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear… (London: J. Dodsley, 1769), 69. ↩

- R.G. Moulton, Shakespeare as a Dramatic Artist: A popular illustration of the principles of scientific criticism, reprint, (London: Oxford 1885). ↩

- E. Hall, Hall’s chronicle : containing the history of England…, (London : Printed for J. Johnson, 1809), 261. ↩

- Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts in the Archives and Collections of Milan 1385-1618, ed. A.B. Hinds, British History Online 37-106. ↩

- Calendar of State Papers Milan 1471, June 2, n218.;

Crowland Chronicler in J. Cox N. Pronay, The Crowland Chronicle Continuations 1459-1486, (York: Richard III and Yorkist History Trust, 1986), 127.;

J. Bruce, Historie of the arrivall of Edward IV…M.CCCC.-LXXI, (London: Camden Society, 1838). ↩ - For accounts of Prince Edward’s death see P.W. Hammond, The Battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990);

Three Books of Polydore Vergil’s English History ed. H. Ellis (London: Camden Society 1950)152;

Hall, Chronicle, 301. ↩ - W. Shakespeare, ‘The Tragedy of King Richard the Third’ in Richard III, ed. T. Cartelli, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2009), 2.2.62-63. ↩

- Tragedy, 3.7.215 ↩

- P. de Commines, ‘Philippe de Commynes: The Reign of Louis XI 1461-83’, ed. Michael Jones, Richard III Society American Branch, Book 6, 225. ↩

- T. More The History of Richard III and Selections from the English and Latin Poems, ed. R.S Sylvester (New Haven: Yale University Press 1976) 90. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.3.1-3. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.3.12. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.3.24-31. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.3.39. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.3.42-46. ↩

- Tragedy, 3.6.1-14. ↩

- Vergil, English History, 167. ↩

- R. Holinshed, Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland:Volume 3, (London : J. Johnson 1808) 346. ↩

- More The History of Richard III, 7. ↩

- Tragedy, 1.1.31-32 ↩

- W. Clemens, Commentary on Shakespeare’s Richard III, eBook, (Abingdon: Routledge Library Editions 1968) 54. ↩

- Tragedy, 1.2.182. ↩

- Tragedy, 1.2.185. ↩

- Tragedy, 1.2.194. ↩

- Crowland Chronicler in J. Cox N. Pronay, The Crowland Chronicle Continuations 1459-1486, (York: Richard III and Yorkist History Trust, 1986), 133. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.1.78-79. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.1.86. ↩

- Vergil, English History, 211. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.2.50-59. ↩

- Tragedy, 4.1.73 & 80. ↩

- Tragedy, 5.3.119. ↩

- Tragedy, 5.3.124-5. ↩

- Tragedy, 5.3.133. ↩

- Tragedy, 5.3.151. ↩

- Tragedy, 5.3.159-163. ↩

- S. Freud, ‘Some Character-Types Met with in Psycho-Analytic Work’ in ‘The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV (1914-1916)’, PEP Archive, 314. ↩