She could have been influenced by her own family’s long association with the Princess Mary.

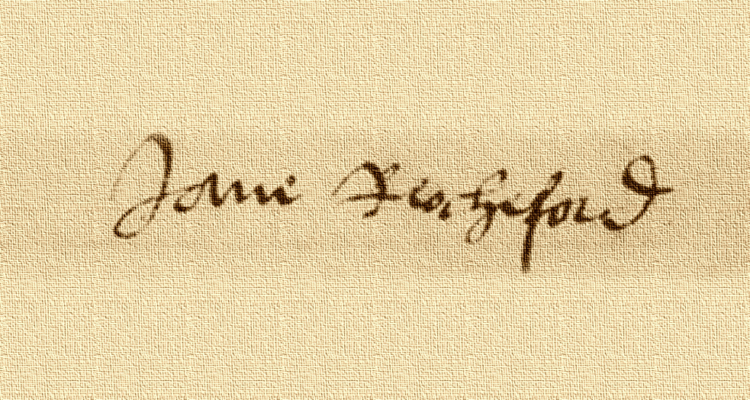

Eric Ives 1

The idea that Jane’s loyalty to her birth family and her father’s religious conservatism caused a rift between the Lord and Lady Rochford has an advantage over other theories put forth by historians and writers, in that it lacks the utter ludicrousness of ideas like ‘jealousy over incest’. It is probably from a desire to have a more scholarly argument that the idea came about in the first place, along with the increasing interest in Jane Boleyn’s father in scholarship. Yet the arguments supporting this idea are still incredibly tenuous. They, firstly, rely on pure speculation, and secondly, are still firmly anchored in the belief that Jane turned on her husband. Therefore, they are setting out to prove that Jane was religiously conservative because she allegedly testified against her husband, and for no other reason. As a result, the idea lacks any substantial evidence. Over the course of these articles, I have shown that the primary sources support that Jane did not testify against her husband George, and her sister-in-law Anne Boleyn, and that she may not have been questioned at all. I have also ruled out, supported by primary sources, than Jane attended a demonstration in support of Princess Mary and was subsequently arrested and imprisoned, or that Jane was rewarded for her part in the coup against the Boleyns by Thomas Cromwell. In the previous article, I began to look at how historians influence the reader by separating Jane from her Boleyn family so these theories are more believable, and what the extant evidence tells us about her relationship with the Boleyns. I discussed Jane and Anne Boleyn’s relationship, and how the primary sources indicate that the two women had a close familial relationship. I will now discuss another aspect of the Rochford’s supposedly problematic marriage, the idea that Jane’s loyalty to her family and to Catholicism came between Jane and George.

When historians say Jane was loyal to her family, they really mean her father, Henry Parker, Lord Morley. It is Morley’s relationship with Princess Mary and his religious conservatism that fuels the idea. Jane’s brother Henry rarely gets a mention, but he was a reformer, and his own son, Jane’s nephew, would become a Catholic exile in Elizabeth’s reign.2 This rather neatly demonstrates that religious views did not, in fact, ‘run in the family’. Jane’s own religious ideals can only be speculated upon. There are simply no primary sources that indicate what she felt ,and no absolute conclusions can be reached. The only thing we can say with certainty is that by 1534, when it is alleged that Jane turned on the Boleyns in support of Princess Mary, Jane had been married for ten years. Only two years into her marriage, Henry VIII had begun to pursue Anne Boleyn. This means that, for the majority of her marriage, Jane Boleyn had been firmly ensconced in Anne Boleyn’s cause. Being young, and we can assume intelligent, it is very likely that Jane, like her brother, influenced by her husband, her sister-in-law, and the young people around her, would have had reformist leanings. When considering this, it should be remembered that the Reformation begun because of real theological issues within the Roman Catholic church. As John Schofield wrote in his biography of Thomas Cromwell, ‘At the core of the Reformation lay the theology of salvation’.3

It may also have been that a part of the shadow which had fallen between [Jane and George] was caused by religion.

David Loades 4

Prior to the ‘King’s Great Matter’, Henry VIII’s pursuit for a divorce from his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, both Thomas Boleyn and Henry Parker were devout Roman Catholics, as was ordinary for people of their standing. I emphases ordinary because one of the biggest problems with this particular aspect of Jane’s historiography is the overemphasis on her father-in-law’s and father’s religious conservatism. Prior to the break with Rome, the overwhelming majority of English people were Roman Catholic. There is simply nothing significant about Wiltshire and Morley’s religious conservatism at that stage. Both Lord Wiltshire and Lord Morley were conscientious subjects who complied with whatever the current monarch decreed. Morley even penned a polemic against the Pope during Henry VIII’s reign, and an essay in his favour during Mary I’s reign,5the former possibly commissioned by Henry VIII himself.6 Morley also adopted the Evangelical habit of calling the bible the ‘word of God’,7 which, as Richard Rex points out, indicates a serious concern with scripture. This is not at all surprising, considering Morley was a scholar.

David Loades speculated that there was a significant relationship between Wiltshire and Jane Boleyn, and that Catholicism connected them, because Jane received an annuity from Wiltshire.8 This is not, in fact, the case, as I have discussed previously. Wiltshire only granted Jane her rightful jointure, what was promised to her upon her marriage, and only after Cromwell intervened to increase the sum to what Jane was owed legally, after a discrepancy in the marriage contract. In his reply to Cromwell, Wiltshire insinuated that Jane was extravagant, and that he had had to live on a lot less at her age. Any ideas of a special relationship are cancelled out by the fact Jane had to write to Cromwell for assistance, and this is something we have documentary evidence of, including Wiltshire’s reply. From this speculation, Loades suggested that religion came between Jane and George, again, from the perspective that Jane testified against her Boleyn family. However, there is simply no weight behind the idea. Wiltshire was at the very least interested in supporting the reformist cause in aid of his daughter, and, as a deeply intelligent man, would have been as interested in scriptural concerns as Morley. It is very doubtful he and Jane had a special relationship over secret Catholicism.

The idea that Princess Mary and Lord Morley had had a ‘long association’ was put forth by both Retha Warnicke and Eric Ives. Ives cites, ‘for the association of the Parkers with Katherine and Mary’ page 30 of Retha Warnicke’s Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn’. Here, Warnicke only mentions that Morley served in Tudor matriarch’s Margaret Beaufort’s household in his minority. Ives also cites pages 6-7 of Warnicke’s Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Reassessment. But in this, Warnicke does not present evidence of an association prior to the first recorded meeting between Morley and Mary, on June 4 of 1536. The gifts of manuscripts to Mary from Lord Morley are vaguely dated as ‘1530s’, yet the first gift from Morley to Mary is not recorded until either 1537 or 1538. David Starkey speculates the first gift of a book from Morley to Mary was made in 1538, because in 1537 Morley’s servant was given 10s as a reward, and only 5s in 1538, as a handmade book had less monetary value. James P. Carley writes that ‘in Mary’s Privy Purse Expenses there are records of gifts to his servant in January 1537 (10s.); 1538, 1540, 1543, and 1544 (5s.). In 1543 and 1544 it is stated specifically that the servant brought a book and no doubt the same is true on the other occasions.’ 9 In either case, it was not before 1537, and certainly not when Mary was in disgrace with Henry, as Warnicke claims,10 as Mary submitted to her father in June of 1536, very shortly after her first meeting with Morley.

One of the major victories of the pro-Mary forces had been the testimony of lady Rochford, the sister-in-law of Anne, who charged that her husband and the Queen had had incestuous relations. That she would offer such vicious evidence makes some sense when it is learned that by the end of 1535 she was estranged from her husband. While the reasons for this estrangement are unknown, they may have arisen from loyalties to Lady Mary inculcated in her by Morley, her father.

Retha Warnicke 11

Calling Morley and Jane part of the ‘pro-Mary forces’ is a wild statement. As we can see, the idea is informed by Jane’s alleged estrangement from her husband ‘by 1535’, a reference to Jane’s supposed arrest and imprisonment for supporting Mary. None of the claims here can be substantiated, that Jane was arrested, that she gave any evidence about incest, or that Jane and George were estranged. We have documentary evidence of Jane attempting contact with her husband and plead with Henry on his behalf after George’s imprisonment. And the idea that Morley instilled any values in Jane regarding Mary is speculation based on Morley’s words to Mary alone. Then again, whether or not Jane admired Mary is really of very little importance. Many at the Tudor court would have secretly sympathised with the abused young princess, and not sought to plot against the Boleyns. The idea has been considered seriously because, buried in Morley’s translation of The Account of the Miracles of the Sacrament, a gift for Mary in 1553, Morley wrote that he had borne Mary ‘love and truth[…]from your childhood’. One popular author even states that this ‘proves that his loyalty to Mary long predated that visit in June 1536.’12.

It does nothing of the sort. The fact is, the Boleyns had been at odds with Mary’s mother, and therefore both Katherine and Mary’s ‘enemies’, from the moment Henry VIII sunk his claws into Anne in 1526. Yet Lord Morley furthered the marriage alliance in 1530, his daughter Margaret marrying Anne Boleyn’s cousin, when the marriage of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon was in the throes of ruin, and Mary herself was being increasingly pushed aside. Of course, all of Henry’s subjects loved Mary, particularly as his only child, and his words certainly may indicate that Morley felt for the young princess during her troubles, as any normal person would have done. But it does not prove, or even suggest, an especial loyalty that would have led him to encourage his daughter Jane to turn on her husband. This is what must be emphasised. These theories are all informed by the desire to demonstrate that Jane turned against her husband, and Boleyn family, and testified against them. Warnicke’s idea that they were estranged is also based on her unfounded theory that George Boleyn was carrying on an affair with Marc Smeaton, a theory that not a single academic has ever given credence to.

The idea that Bishop Fishers execution turned the Parkers against the Boleyns, as Lord Morley had been friendly with him and he had been Margaret Beaufort confessor, is also tenuous. Again, it would need to be demonstrated, and not merely speculated on, that Morley would have been so incensed at the Boleyns that he encouraged Jane to endanger her own life. And it wasn’t the Boleyns who swung the axe. Whatever private horror Morley felt, he, along with so many other subjects, could only sit silently through his monarch’s wave of destruction. Morley, as mentioned, was, perhaps even happily castigating the Pope on Henry’s behalf only a few years after Bishop Fisher was executed.

So when did Lord Morley and Lady Mary’s friendship begin? The first record of a meeting was June 4, 1536. This was recorded in August 1536 when Anne, Lady Hussey, was interrogated in the Tower about visiting Mary at Hunsdon. Lady Hussey said Lord Morley had been amongst the visitors there, and perhaps his wife and daughter, but this is questionable as the manuscript source is mutilated.13 Julia Fox speculates that Morley took his younger daughter Margaret, whose mother-in-law Lady Shelton was in Princes Mary’s household. It should be kept in mind though, that Mary was still in disgrace, but submitted to her father very shortly after Morley’s visit.

Why did Morley visit Mary? Mary had, in fact, moved into Hunsdon House with young Elizabeth in early in 1536, Chapuys having mentioned they were being moved there at the end of January. Hunsdon was six miles from Morley’s seat at Great Hallingbury. At this stage Morley was attending the last Reformation Parliament, which lasted from 4 February to 14 April. He may have come home and perhaps even presented himself to his new neighbours before he was summoned back to court for the trial of Anne and George Boleyn in May. Perhaps we can assume Jane had come back to Hallingbury after the executions. Morley’s visit to Mary in June would have been brief, as he was summoned back again for an emergency parliament which recognised the divorce and execution of Anne, and the elevation of Jane Seymour, which ran from June 8 to July 18.14

In the absence of any documentary evidence, and as David Starkey notes, Mary’s household records are quite complete, it seems obvious that Morley’s visit with Mary was of a subject visiting his new royal neighbour. The first gifts received by Mary from the Parkers and Jane were recorded in January 1537, presumably New Year’s gifts. So it is obvious the friendship began after that meeting in June 1536, and endured until Morley’s death. Whatever happened after this between Morley and Jane and Mary is irrelevant. The inference was that the Parkers had an association with Mary from childhood which prejudiced them against the Boleyns and encouraged Jane to turn against her husband. As we have seen, the documentary evidence does not support this.

When we think about Mary and Jane exchanging gifts the next year, Jane presenting Mary with a clock, and Mary later gifting Jane twelve yards of black satin for her widow’s wardrobe at the sum of £4, it is useful to think of Mary as a young woman coming to the realisation that Anne Boleyn was not the only reason her father destroyed her mother. If the reader takes a moment to set aside the Disneyish ideas of plotting and revenge and reward, it’s easy to see that Jane and Mary had a conventional royal-to-courtier relationship, and we can hardly deduce that Jane’s feelings for Mary were so reverential that she destroyed her husband, his family, and her own life, for the princess. The idea simply has no credibility. Whatever friendship the women may have shared in the aftermath of the executions was born in the grief caused by Mary’s father, and the terrible losses both Jane and Mary suffered for Henry VIII’s maniacal desire for a son.

- E. Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, (Second Edition, Oxford: Blackwell, 2004) 332. ↩

- D. F. Coros, ‘Parker, Sir Henry (by 1514-52), of Morley Hall, Hingham, Norf. and Furneux Pelham, Herts.’ History of Parliament ↩

- J. Schofield, Thomas Cromwell: Henry VIII’s Most Faithful Servant, (eBook, Stroud: History Press, 2011) 890. ↩

- D. Loades, The Boleyns: The Rise and Fall of a Tudor Family (eBook, Stroud: Amberley Publishing 2011) 230. ↩

- M. Axton, J.P. Carley, eds., ‘Triumphs of English’ Henry Parker, Lord Morley, Translator to the Tudor Court: New Essays in Interpretation (London: British Library, 2000) 87. ↩

- Triumphs of English 89. ↩

- Triumphs of English 97. ↩

- Loades, Boleyns, 203-35. ↩

- Triumphs of English 18 & 44. ↩

- R.M. Warnicke, ‘The Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Reassessment’, History, 70:288 (February 1985) 6-7. ↩

- Warnicke, Reassessment, 6. ↩

- A. Weir, The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn, (eBook, New York: Ballantine Books, 2009) 294 ↩

- Triumphs of English 14. ↩

- Triumphs of English 16. ↩