When the remains of Richard III were formally identified in 2012, it led to new discoveries about his life and times. Among the results of various investigations, it was determined that in the last two years of his life, Richard ate a much richer diet and drank more imported wine, rather than more locally derived beverages.1. This discovery was hardly surprising as kings were expected to hold more feasts and banquets, and entertain on a much grander scale than a duke, for example.

Unsurprisingly, in Medieval times access to, and the variety of, food available was sharply different according to social class. According to Ian Mortimer, most people only had two meals a day. The main meal was dinner in late morning, that is, around 10 am or 11 am. A second, smaller meal was soupier or supper, eaten in late afternoon between 4pm and 5pm, although the nobility would often eat later in the day. Only the wealthy and noble households indulged in breakfast. Availability of food was further restricted by the Church which forbade the consumption of meat on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays, as well as throughout Lent and Advent. In addition, the consumption of eggs was forbidden in Lent. The Church’s restrictions applied to everyone, rich and poor alike. 2.

The nobility had an inbuilt advantage when it came to the provision of food as they could utilise their estates to provide freshly killed meat and river fish, as well as other produce. The wealthier the noble, the greater his estates and the more extensive the range and variety of food provided. It was only to be expected that kings, with their royal estates spread around the country, would provide the richest variety of food to feed their court and important visitors. However, that is not to say that their diet was particularly healthy. The wealthy ate few fresh vegetables and little fresh fruit as unprepared food was regarded with suspicion. Raw fruit in particular, was thought to cause disease, so it was eaten in pies or preserved in honey, while vegetables were included in some form of stew, soup or pottage. The vegetables most likely to be found on a noble’s table were rape, onions, garlic and leeks. With the consequent lack of Vitamin C and fibre, diners suffered an assortment of health problems. 3

Other ingredients used included cane sugar, almonds and dried fruits such as figs, dates and raisins. These, together with the spices, were very expensive and the royal court had a separate department, the Spicery, which was entirely devoted to obtaining, storing, safeguarding and using these valuable items.

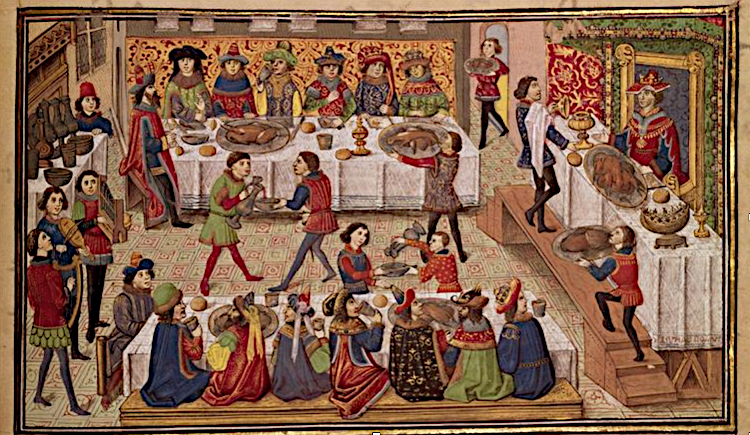

Banquets involved the use of spectacular dishes. Alongside the everyday pies, jellies, fritters and stews, were dishes containing unusual animals such as peacocks, seals, porpoises and even whales. To enhance the display of particular dishes, items such as jellies and custards, were dyed, using sandalwood for red, saffron for yellow and boiled blood for black. 6

A significant part of any banquet was the subtleties, creations made of sugar, marzipan, pastry, wax, paper and paint. Subtleties were considered to be part of the entertainment and were brought out at the end of every course. There is no existing information regarding the subtleties used at Richard’s coronation banquet, although we do know that Henry V, for example, used his personal emblems as a theme at his. The subtlety at the end of the first course was a swan surrounded by cygnets, all of whom carried messages in their bills that were lines of verse. Twenty-four more swans followed, each one carrying the last line of the poem. Later subtleties included an antelope and an eagle. Each had a motto promising good government and chivalric ideals. His son, Henry VI, used subtleties to show his descent from St Louis and Edward the Confessor and his right to rule in France. 7

The enthronement of George Neville as Archbishop of York in 1465 was documented in great detail, including the banquet which Richard attended. There were several courses, each of either twelve or twenty-four dishes. Every dish in a course was brought out at the same time and set on the table until removed and replaced with dishes of the next course. These courses were not separated into savoury main courses and sweet dishes, instead savoury and sweet dishes were laid out together. Although to modern eyes, the quantity of food seems overwhelming, it was the practice in medieval times to take only a small portion of each dish as left-overs were given to the poor and represented an essential part of a noble household’s contribution to charity. 8.

In addition, nobles seated at the most important table who were served separately were expected to offer choice portions from their dishes to favoured guests.

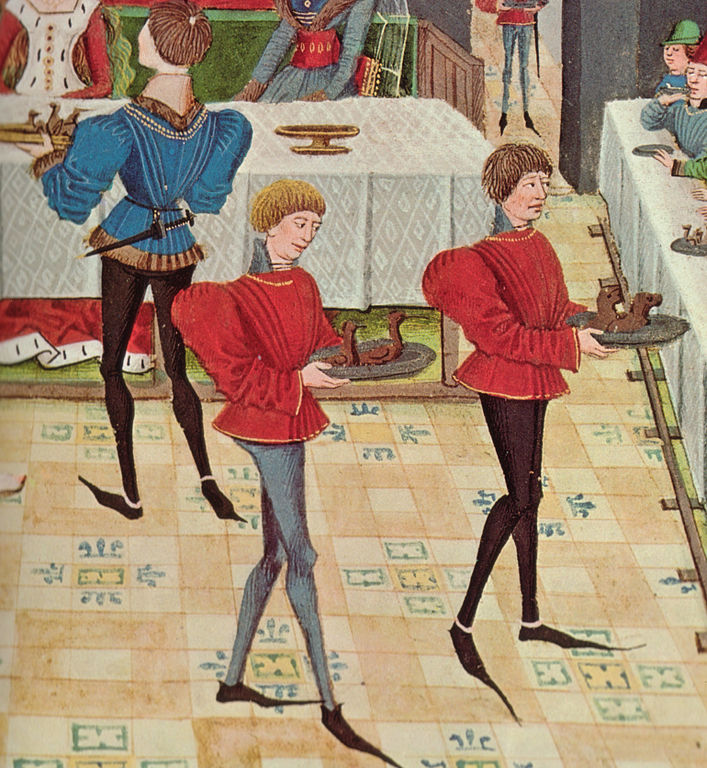

Dishes provided in each course were not simply chosen haphazardly, but followed certain principles. Olivier de la Marche, who was associated with the Court of Burgundy for many years, and was considered an expert in matters of ceremony, said that foods should be served in the order of soups, eggs, fish and meat, then the entrements (an elaborate form of entertainment dish common among the nobility and upper middle class in Europe during the later part of the Middle Ages and in England known as subtleties.) such as swans, or peacocks in their plumage and lastly desserts. When there was more than one course, this rule was observed not only overall, but within each course. Richard’s coronation banquet followed these rules. 9

A coronation banquet was not simply an opportunity to enjoy fine food. During the Medieval period, it became increasingly important as a means of displaying the king’s state and largesse, the dignity of his household and the ranks of his servants. All the best gold plate was on display, along with gold and jewelled salt cellars for the king’s own table.

It is very likely that the Royal Gold Cup would have been a centre piece of the display. This cup had belonged to French kings from the end of the 14th Century until it came into the ownership of John, Duke of Bedford, Regent of France, then after his death it became a possession of the English Crown. It was made of solid gold, decorated with pearls, sapphires and rubies. It was not meant to be used, as it weighs over 1.9 kg. The cup is now in the British Museum.

Also on display were the skills of the carvers, servers, panter, butlers and marshals of the hall. A well organised coronation banquet showed how well the king led his realm.10

Among the surviving documents relating to the coronation of Richard III are those concerned with his coronation banquet, as well as the meals eaten on Friday evening and the morning and evening of the Vigil (Saturday). The record of the coronation banquet is considered to be an especially fine one which underlines the cooperation between the royal household departments involved in producing it. It was a feat of organisation and coordination by the Household from the treasurer down to the serjeant of the Scullery as well as the various lords and gentlemen who had official duties at the banquet, for example the King’s cup-bearer, carver, chief butler etc.11

As Fridays and Saturdays were meat free, the menus for the evening meal on Friday and dinner and soupier on Saturday show an extensive range of both fresh water and salt water fish dishes on offer. For example, the first course on Friday included tench, bass, conger eel, salmon, sole, perch, roach, freshwater crayfish, trout and porpoise.

Preparation of the dishes involved the use of 2 pounds of pepper, half a pound of saffron, 1 pound of ginger, 12 pounds of sugar, 4 gallons of pott sugar (ie sold in barrels), 1 pound of cloves, 1 pound of sandalwood (for colouring), 8 pounds of dates, 8 pounds of raisins, 6 pounds of prunes, 20 pounds of almonds, 2 pounds of aniseed, 20 pounds of whole rice, 2 pounds of red and white confits (sweetmeats) and 2 gallons of olive oil.

Also required were 50 gallons of milk, 10 gallons of cream, 1,000 eggs, 6 gallons of butter and a quantity of gret onyons.

The evening meal, or soupier was the smaller meal of the day!

Dinner at the Tower on Saturday, when the new Knights of the Bath received their accolade, involved 6 dozen salt lamperns (river lamprey), 112 dozen salt eels, 250 pikes, 16 gret turbuttes (turbot), 6 gret halibuttes, 600 gret places (plaice), 12 conger eels, 12 salmon, 48 soles, 2 barrels of salt sturgeon, 3 semes (ie horse loads) of crabs, 26 salt salmon, 300 fresh eels, 800 roach, 1,000 welks and 6,000 forland welks.12

The coronation banquet was the final ceremony of Richard’s coronation celebrations and a final chance to create a good impression. It is possible to make a reasonable estimate of the number of people who were accommodated at the banquet based on the number of messes specified in the documents. There is a slight discrepancy between them, but catering provided for a minimum of 1,000 messes and a maximum of 1,200 messes. (A mess is a portion of a dish of food serving one or more persons.) There were rules about how many people shared a mess according to rank. People equal in rank to bishops or marquesses sat 2 to a mess; people equal in rank to a baron or mitred abbot sat 2 or 3 to a mess; all ranks equal to a knight sat 3 or 4 to a mess and squires sat 4 to a mess. In addition, 3,000 wooden cups were provided. So it is reasonable to suggest that at least 3,000 people were fed.13

To feed these 3,000 people, the banquet used 30 bulls, 100 calves, 140 sheep, 148 peacocks, 218 pigs and 156 deer of various types. To prepare the various dishes, 20 pounds of powdered pepper, 8 pounds of whole pepper, 4 pounds of long pepper, 4 pounds of whole ginger and 2 pounds of minced ginger were used. The Spicery provided an additional 16 pounds of powered ginger, 150 pounds of almonds, various types of sugar, including 150 pounds of Portuguese sugar. 14

The banquet had three courses of 16, 16 and 17 dishes. Large quantities of red and white wine were served alongside the food. To get a flavour of the range and type of dishes involved, let’s look at the sixteen dishes of the first course.

After a proclamation by a herald, the dishes were brought out.

Potage: Frumentie with venison and bruett Tuskayne (Frumentie is a dish of boiled wheat, milk, cinnamon and sugar. This version contained venison and a Tuscan broth.)

Viand comford riall (Some sort of meat – fit for a king)

Mamory riall (A dish made of small pieces of brawn, capon or partridge)

Beef and mutton

Fesaunt in trayne (Pheasant with tail feathers displayed)

Cygnet rost

Crane rost

Capons of hault grece in lymony (Fat or crammed capons possibly with lemon)

Heronshewe rost (Young heron)

Gret carpe of venison rost (Shredded or sliced venison)

Grett luce in eger doulce (A full grown pike in a sour-sweet sauce)

Leche solace (A kind of jelly with many different flavours – may be cut into leches or slices)

Fretor Robert riall (Batter covered food fried in deep fat)

Gret flampayne riall (A pie or tart decorated with points of pastry)

Custard, Edward planted (A custard is an open pie)

A subtlety 15

The second course included peacocks, roe deer, partridge, venison, carp, Scotwhelpes (a member of the snipe family), jellies and tarts. It was during the service of this course, that the king’s champion, Sir Robert Dymock, armed from head to toe, on a horse caparisoned in red and white silk, rode into the hall, cast down his gauntlet and issued his challenge to anyone who disputed King Richard’s right to the crown. There being no takers, he was offered wine in a gold cup, which he drank and kept the cup as his fee.

Sadly, the third course was never served as the banquet, which had started at 4pm, over-ran and went on into the summer evening by torch light. Sutton and Hammond speculate that the length of the banquet is the best argument for its success. The banquet was an opportunity for the king to pick out and honour people with royal attention and it seems that Richard spent a lot of time talking to people which further delayed service and led to the abandonment of the third course. Lessons were learned for future coronation banquets. Henry VII, for example, only had two courses totalling 48 dishes at his with the same number for the coronation banquet of Elizabeth of York. 16

As Richard retired for the night on the 6th July, he could reflect on a very satisfactory ten days since he had taken possession of the crown. Apart from the issue with the third course at the banquet, the rest of the ceremonies had gone well. All departments of the royal household had performed efficiently, the Great Wardrobe had provided all the necessary clothing, furniture and artifacts, the coronation ceremony had gone like clockwork and he could look forward to his royal progress later in the year.

- Scientific American, ‘Richard III Really Ate and Drank Like a King’, Scientific American 2014 (website)<www.scientificamerican.com/article/Richard-iii-really-ate-and-drank-like-a-king> ↩

- Mortimer, Ian The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England, Bodley Head London 2009 pp 167-168 ↩

- Lords and Ladies ‘Middle Ages Food and Diet Lords and Ladies (website)

<www.lordsandladies.org/middle-ages.food-and-diet.htm> ↩ - History of Alexander the Great manuscript from the collections of the Musee du Petit Palais, Paris ↩

- Bovey, Alex ‘The Medieval Diet’ British Library (website)<https://www.bl.uk/the-middle-ages/articles/the-medieval-diet> ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Hammond, PW, & Sutton, Anne F., The Coronation of Richard III: the Extant Documents, Alan Sutton, Gloucester, 1983 pp. 283-284 ↩

- Boyd, Lizzie (Ed) British Cookery: A complete guide to culinary practice in the British Isles. Revised edition, Croom Helm Ltd, London 1977 pp 10-11 ↩

- Sutton and Hammond, Op cit 287 ↩

- Ibid p 283 ↩

- Ibid p 284 ↩

- Ibid pp 291-292 ↩

- Ibid p 285 ↩

- Ibid pp 286-287 ↩

- Ibid p 294, also see Glossary pp 416 – 435 ↩

- Ibid p 286 ↩