Shylock has been residing in a corner of my mind for about four years now, ever since I first studied The Merchant of Venice. I’d like to say ‘quietly’, but he’s not always quiet. I think about him when I am watching or reading Shakespeare’s other plays. He is often the subject of discussion in my household. For the last two years, while I’ve been researching another of Shakespeare’s iconic ‘villains’ in The Tragedy of Richard III, Shylock has been there; reminding me of the parallels between him and Richard, as I read Richard from an empathetic viewpoint. And, a little over two weeks ago, he began following me around, loudly. The Globe’s candlelight performances of The Merchant of Venice launched on February 22nd, prompting the Evening Standard to ask “Is it time to put The Merchant of Venice to bed?”.1 It is the same controversy that is rolled out every time the play is staged, was Shakespeare an anti-Semite, is there a danger of perpetuating anti-Semitism whenever it is staged?

While I have been revisiting Shylock, Russia invaded Ukraine. The media coverage has been outrageously racist, essentially insinuating the situation is ‘more shocking’ than invasions of Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, because the refugees are white, and ‘civilised’. It prompted a statement from the Arab & Middle East Journalists Association that they categorically reject “orientalist and racist implications that any population or country is “uncivilized” or bears economic factors that make it worthy of conflict. This type of commentary reflects the pervasive mentality in Western journalism of normalizing tragedy in parts of the world such as the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. It dehumanizes and renders their experience with war as somehow normal and expected.”2 Why did I see a connection? What did Shakespeare’s Shylock suffer, after all? Shylock was also considered uncivilised, and also expected to put up with brutality and oppression, even though he and his fellow Jews played an important part in the Venetian economy. It’s yet another reminder that we haven’t come so far in four centuries. I always see Shylock, everywhere.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with Shylock, despite his distinctly English name, Shylock is a Venetian Jew, an ostensibly minor character in the so-called comedy The Merchant of Venice. In the play Shylock demands a pound of flesh from the supposedly upright Christian merchant Antonio, for failing to make payment on his loan. The play was adapted from the Italian novella Il Pecorone, which provides a lot of the framework; a rich heiress to be won, a merchant at the mercy of a Jewish banker, the ‘pound of flesh’ bond, and the court room scene with the heiress disguised as a young male lawyer who ‘saves the day’. What it doesn’t provide is any story, or even a name, for ‘the Jew’. Shakespeare’s Shylock, who has far less stage time that other characters, somehow steals the whole show. The reason why we argue over the play’s alleged anti-Semitism is because Shylock is a fully realised character with a compelling narrative, and we cannot dismiss him as a caricature. His Jewishness is a profound part of his identity. He hates the Christian Antonio, because Antonio spits on him and undermines him at every opportunity. When his daughter is stolen, yes, stolen, from him, he is hell-bent on revenge. When he is thwarted and terribly punished, we grieve for him. There will always be an argument over the nature of Shylock, but the text gives us far too much material to be able to universally agree that it is anti-Semitic.

Merchant was likely written in response to a successful revival of Christopher Marlowe’s Jew of Malta, which features the Jewish villain Barabas, who conducts wholesale slaughter throughout the play. Marlow’s Jew has long been considered viciously anti-Semitic, although some critics have posited it as anti-anti-Semitic, a deeply ironic portrayal. Although Merchant’s text indicates Shakespeare’s sympathy for Shylock, it is possible that Shylock, in Shakespeare’s time, was also performed as a comic villain. In 1701, George Granville adapted Merchant, in his Jew of Venice. Granville stripped much of the original text, including Shylock’s, romanticising the Christians as beacons of friendship and morality, and reducing Shylock to a caricature villain. However, Shylock was rescued from that portrayal in 1741 by Charles Macklin. While Macklin still played him as a villain, he played Shylock with deep gravity, and attention to authenticity, trimming his beard in the style of a Venetian Jew.3 By the time Edmund Kean took him on in 1814, Shylock was causing the audience to weep. And since then, something in Shylock’s journey throughout the play has captured the sympathy of audiences. We have seen it in performances, and, as an audience, we have felt Shylock’s pain. The current conversations around anti-Semitism in Merchant are really disingenuous, especially now, especially when we read Shylock in the lingering shadow of the Holocaust. ’How do we make Shakespeare less terrible?”, shrieks the Standard.4 It’s fairly straightforward. The ‘terribleness’ of Shakespeare lies mostly in performances. The text has always given us scope to do better.

Abigail Graham’s upcoming production for the Globe will focus on “how white Christian men use their power to pit minorities against each other. That’s the conversation we need to be having.”5 It’s exactly the conversation we need to be having, and now is exactly the time to be having it. It’s also evident that this is the sort of reading we can only make in the 21st century. It shows how the play has been able to evolve over the centuries. In the 19th century we had profoundly sympathetic portrayals of Shylock, the play sometimes being called the Tragedy of Shylock. Then in the 20th century Shylock was appropriated by the Nazis as anti-Semitic political propaganda. The post-Holocaust era saw Jewish audiences deeply uncomfortable with the character, and no doubt audiences in general. It has only been in the last couple of decades that this has subsided.6 Some scholars complain that we see the play as empathetic because of our own values, but that doesn’t cancel out Shakespeare’s intent, or what we can make of it. The plea for Shylock’s humanity has always been there. Shakespeare’s idea of a Jew may not have been entirely authentic, but we can make Shylock so now.

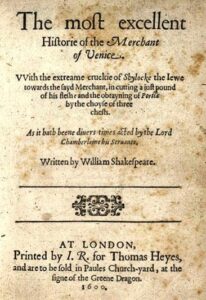

The lingering question is, was Merchant written as an anti-Judaic play in order to perpetuate harmful stereotypes against Jewish people? The broad answer is no, and that is evident in the text. It is certainly apparent Shakespeare was exploiting English anti-Judaism, and anticipated his audience’s feelings towards Shylock. The Quarto covers are subtitled ‘with the extreme cruelty of Shylock the Jew’. Merchant does depict anti-Semitism, and it contains anti-Semitic language, mostly in the form of Shylock being addressed as ‘Jew’, ’dog’ and ‘devil’ and variations upon those. It is constant, and dehumanising, abusive language. It’s also an accurate representation of a Jewish person’s experience in Renaissance Europe. Even Merchant’s unrelenting critics admit that the conclusion of the play indicates that ‘Shakespeare knew that Jews were human beings like other people’.7

We, the modern audience, find the racist language and action exhausting. As Shylock’s plight is framed within a comedy, much of the Elizabethan audience likely would have responded to Shylock as absurd, to begin with at least. But the forced conversion to Christianity, Shakespeare’s own invention and not in any of his sources, indicates that he was addressing something topical, in a Protestant country where Catholics and Jews were practising their faith in secret. Certainly, much of the contemporary audience probably thought Shylock got what he deserved, but that doesn’t prove it was the text’s intent. Abdulla Al-Dabbagh dubs Shakespeare’s explorations of prejudice, in plays like Othello, Cleopatra, and Merchant, a ‘reversal of stereotype’.8 Shakespeare presents these (what we now call) stereotypes through the characters, and then he subverts them, through speech and action. It seems that Merchant, and its critique of Christianity, is a plea for religious tolerance, in a time when there was none.

It is correct, though, that even as Shakespeare subverts these stereotypes, he also depicts them. Fifty years ago Leslie Fiedler wrote that: ‘the play in some sense celebrates, certainly releases ritually, the full horror of anti-Semitism. A Jewish child, even now, reading the play in a class of Gentiles, feels this in shame and fear, though the experts, Gentile and Jewish alike, will hasten to assure him that his responses are irrelevant, even pathological, since “Shakespeare rarely takes sides”’.9 I don’t view the play as a celebration of anti-Semitism, but Shakespeare does expose his audience to a piercing portrayal of intolerance and anti-Judaism. And any text is exploitable. Nazi Germany appropriated Shylock. How could Shylock not have caused fear and shame in a Jewish audience?

Recently, a short piece appeared in The Times about the content warnings The Globe are using in their new production of Merchant, simple warnings like the sort we have seen on television for decades. Yet they cry, over dramatically, ‘How have we come to this after so many years of Shakespeare?’.10 Fifty years ago, with far less widespread understanding of trauma, Fiedler told us how a Jewish audience reacted to Shylock. It was a trigger. It will remain one for some. So, how have we come to what? Respect for audiences? Knowing that those audience members might feel Shylock’s plight personally, deeply, uncomfortably, shatteringly? You can’t claim that the play’s alleged anti-Semitism will harm Jewish audiences and then squawk about content warnings. Merchant is still deeply disturbing, and always will be.

After the Globe’s 2016 production, starring Jonathan Pryce as Shylock, the Washington Post called for Merchant to be banned, claiming “it’s impossible to ignore its sickening anti-Semitic language[…]even worse is the play’s revival of ancient racial slurs.”11 As a historian, there is nothing stranger than the idea that we would look away from history. I ask why the audience, especially the non-Jewish audience, thinks it has the continual right to keep their eyes closed? And in the 21st century this is a growing problem. If you are able to, if you don’t have a compelling trauma-related reason to be protected from confronting material, then it is your responsibility as a human being to see. The world is running far too low on empathy. If seeing Shylock spat on, insulted and oppressed, makes you uncomfortable, upsets you, then good. That is what it’s supposed to do.

Anti-Semitism, from the mid-20th century onwards, was understood in the shadow of the Holocaust, and the deep anxiety it caused in society, the (rightful) shame that such an atrocity happened in our time. But it only happened 80 years ago, and it wasn’t a spontaneous event. Götz Aly12 traces 150 years of tension prior to WWII in Germany alone, and before that, many centuries before that, Jewish people suffered Christian persecution because of difference in faith. But the word anti-Semitism is becoming weaponised, often used against criticism of the Israeli government’s human rights violations. Just last month, human rights group Amnesty International became a target for accusations of anti-Semitism for branding Israel’s treatment of Palestinians apartheid.13. What is an anti-Semite now? The Holocaust is leaving living memory. We’ve seen the insidious return of overt racism, amplified by social media and the persistent decline in intellectual climate. If there is ever a time to ‘cancel’ Merchant of Venice, it is not now. Now is the time to remember. Now is the time to think about why Shylock has haunted us for four hundred years, and wonder if he will haunt us for centuries to come.

Featured image: © The Globe. Adrian Schiller playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice (2022). Photographer: Tristram Kenton

Read Part Two in our Merchant of Venice series: History and Myth

- A. Saville, ‘From The Merchant of Venice to Romeo and Juliet, how do we make Shakespeare less terrible in the 21st century?’ Evening Standard, Feb 16 2022 ↩

- The Arab and Middle Eastern Journalists Association (AMEJA) ‘Statement in Response to Coverage of the Ukraine Crisis’, AMEJA Feb 2022 ↩

- D. Donaghue, ‘Macklin’s Shylock and Macbeth’, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, 43:172, 1954, 424. ↩

- Evening Standard ↩

- Evening Standard ↩

- J. Shapiro Shakespeare and the Jews (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016) viii. ↩

- D. Cohen, “Shylock and the Idea of the Jew” The Merchant of Venice, ed. Leah S. Marcus, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company) 193-206. ↩

- A. Al-Dabbagh, Shakespeare, the Orient, and the Critics (new York: Peter Lang, 2010) 15-49. ↩

- L.A. Feidler, The Stranger in Shakespeare, (London: Croom Helm, 1972) 98-99. ↩

- Globe to add warnings to Shakespeare.” The Times, 24 Feb. 2022, p. 13. ↩

- S. Frank, ‘The Merchant of Venice’ perpetuates vile stereotypes of Jews. So why do we still produce it?, July 28 2016. ↩

- Götz Aly, Why the Germans? Why the Jews? Envy, Race, Hatred and the Prehistory of the Holocaust, tr. J. Chase, (Melbourne: Mebourne University Press, 2014. ↩

- L. Berman, Lapid Attacks Delusional Amnesty UK Ahead of Report Accusing Isrel of Apartheid, Times of Israel, Jan 31 2022 ↩