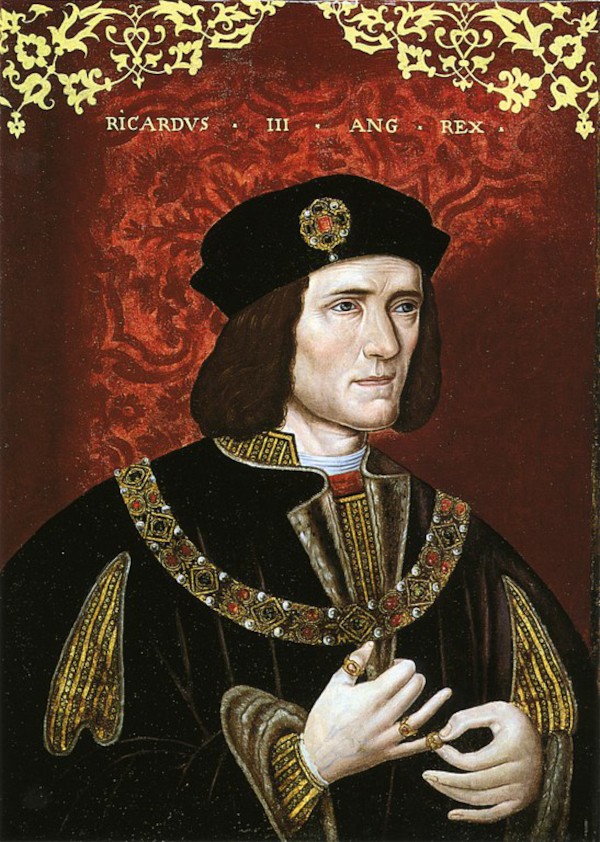

Please note that the historical figure King Richard III will be referred to as ‘Richard III’, and Shakespeare’s character Gloucester/King Richard as ‘Richard’ throughout these articles.

When I began research on my thesis a little over two years ago, I thought I was asking an impossible question. Who exactly was William Shakespeare’s King Richard III? When I first watched the play in 1995, it was the film adaptation starring Ian McKellen. I thought it was a wonderful satire, and I had no sense whatsoever that this was a true representation of a historical figure. When I joined the Richard III Society in 2014, I heard more and more of the idea that Shakespeare had written The Tragedy of Richard III with the sole purpose of blackening Richard III’s name as part of a ‘Tudor propaganda’ campaign. Rather than this idea becoming more believable as I learned more about the historical Richard III, it became less so. This wasn’t because of any research I had done into the Tragedy. I had still only watched Ian McKellen as Richard and I hadn’t read the whole play. But I had watched a lot of Shakespeare’s other plays by that time, and the more plays I watched, the less convincing the idea that Shakespeare wrote ‘Tudor propaganda’ became.

I first saw The Stranger’s Case in the Globe’s 2018 short film for International Refugee Day. It was a speech written by Shakespeare that I had never heard before, part of a collaboration on The Book of Sir Thomas More. Its cry for compassion in the face of anti-immigrant riots was one of the most moving of Shakespeare’s speeches I had heard. When I took a Shakespeare class that same year, I was introduced to the concept of ‘Strangers’ in Shakespeare through Merchant of Venice, characters who are marginalised by culture or religion or gender. And I began to wonder if Richard himself could be considered one of Shakespeare’s ‘Strangers’. I began my research only with an unshakeable instinct that the Tragedy was misunderstood, like Othello, Cleopatra and Merchant of Venice, are often misunderstood. I wasn’t supremely confident. But almost immediately, I found evidence that the play was not only misunderstood, but had, as Edward Burns puts it ‘escaped from its creator, into the wilderness of a disturbing psychological and historical terrain ’.1 Not only was an inauthentic version of the play performed over the 18th and 19th centuries, only about half of the play text is usually performed now. The historical context of the play, as a part of a tetralogy with the Henry VI plays known as The Henriad, is completely lost in the severe editing. Without the historical context Shakespeare’s Richard becomes a murderer without purpose, and those who were his collaborators, merely hapless victims. In the 21st century Richard has become a full-blown psychopath, the public thirst for on-screen gore, and violence against women in the pursuit of ‘reality’, deepening his depravity.

But this is not Shakespeare’s Richard. Shakespeare’s Richard was a complex man, a villain indeed, but also a man who became corrupted by the greed and violence of his surroundings. Shakespeare’s Richard sits on the periphery of an avaricious group of nobles, plotting against them, yes, but also drawing the audience into his schemes, making us admire him. Shakespeare’s Richard is not always the Richard you see on stage, or screen, now. And a historian’s perspective on the play makes this all the more evident. Literary scholarship on the Tragedy is wonderfully diverse, but lack of historical rigour exposes weaknesses. We can’t appreciate the full text of the Tragedy if we don’t know the history. But we also can’t understand the Tragedy if we cling to ideas about ‘Tudor propaganda’. When I began my research, I sought an empathetic reading of the Tragedy, and I found it, easily. But I also found commentary on the plight of powerless women, on the citizens’ duty to Monarch over God, and loyalty to family, on the destruction that can be caused by weak leadership, and the subversion of stereotypes about disability in the early modern era. A lot of critics are dismissive of the Tragedy because Shakespeare was less skilled in the early part of his career, but Richard was Shakespeare’s first really complicated character, the blueprint for villains like Iago and Macbeth.

While popular culture has created an image of the Tragedy as an exercise in blackening Richard III’s name, the text reveals that Shakespeare questioned the Tudor image of Richard while he portrayed it. When Richard says I am a villain. Yet I lie. I am not, he is not just questioning his feelings about himself, he is struggling to break free of an image ingrained in history. In this first article in this series I will be questioning the veracity of the idea of a dedicated ‘Tudor propaganda’ campaign and Shakespeare’s supposed role in it.

Was Shakespeare a ‘Tudor Publicist’?

‘Tudor Publicist’ is how novelist and ardent Ricardian Philippa Gregory described Shakespeare in a 2021 interview for the Richard III Society’s Ricardian Bulletin.2 It is a typical expression of a long-held Ricardian belief. When I use the term ‘Ricardian’, it does not refer to the Richard III Society specifically, it refers to all those interested in, and fans of, the historical figure. Although, in this case, the society itself has been instrumental in maintaining the pervasive idea that Shakespeare was a ‘Tudor Propagandist’, and it became more popularised after the discovery of Richard III’s lost grave in 2012. In earlier years, the society was more forgiving towards Shakespeare, acknowledging that he was only working with the sources he had available. But as the years have gone by, and actors have interpreted Richard in increasingly violent ways, the antipathy towards the Tragedy has increased.

The ideas that the Tragedy was written to flatter Elizabeth I, or that Shakespeare would have had his head struck off had he written well of Richard III, or that the memory of Elizabeth’s long-dead great-uncle posed any threat to her, have no credibility. They are grounded only in popular thought and not scholarship. There’s little to expand on here, other than to reinforce that there was no need to slander Richard III on behalf of the Tudor monarch over 100 years after his death. Some conjecture that Shakespeare was hindered by censorship, but the Tragedy contains nothing particularly seditious. Topical allusion, rather than history, is what the Master of Revels sought to contain, and within acceptable limits rather than eradicate it altogether3 A good example of what attracted censorship is Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Richard II. The scene in which King Richard II is deposed apparently corroborated with the 1595 A Conference upon the Next Succession by Doleman (Robert Parsons). Parsons’ book promoted the Catholic resistance theory, justifying disobedience to the monarch, and also denied the Tudor succession’s legitimacy and favoured the Spanish claim via John of Gaunt.4 Shakespeare’s Tragedy contains no such scenes that would attract the especial attention of the Elizabethan government, nor is it more than conventionally flattering to Elizabeth I’s grandfather Henry VII, despite popular belief.

Was King Richard III a victim of ‘Tudor propaganda’?

The idea of King Richard III being a victim of Tudor propaganda forms the basis of much Ricardian writing, but it has also become deeply exaggerated over the years. ‘Tudor propaganda’, or mythology, correctly refers to Henry VII’s attempts to strengthen his tenuous blood claim to the throne by claiming descent from ancient British King Cadwaladr, and the public image he built up around himself and his family; Henry’s marriage to Elizabeth of York was fabled as a unification of the white rose of York and the red of Lancaster, to end all conflict. But in popular thought that goes back several centuries, the Tudors spent their reign, from Henry VII to Elizabeth I, maligning Richard III in aim of maintaining their claim to the throne, as if the legacy of someone who reigned for two years consumed the entirety of their thoughts for over a century. Horace Walpole, writing in the 18th century, accused the Tudors of ‘retaining their Lancastrian prejudices, even in the reign of queen Elizabeth’.5 Another well-known Ricardian writer, Clements Markham, writing in 1906, was far more flamboyant. Markham claimed that Henry Tudor had no valid claim to the crown, that any writing in favour of Richard had been destroyed, that only Henry’s ‘paid historians’ were allowed to write and they were ‘very well paid counsel and witnesses of Richard’s cunning enemy’. He reserves particular venom for Polydore Vergil, claiming Vergil misrepresented facts ‘not only to please his patrons, but to gratify his own spite and malignity’. According to Markham, ‘not a syllable was allowed to be uttered on the other side for 160 years’,6 although he was ignoring the fact that there had been several publications defending Richard III from the 17th century onwards. Common sense should rule out the Tudor dynasty quailing in terror at the thought of Richard III’s memory, however, Markham’s spiteful influence can be seen in 20th century publications and beyond.

Despite the tenacity of the idea, there is no real evidence of a concerted campaign by Henry VII to denigrate his former rival. Henry’s official word on Richard III in his first parliament mentioned ‘Perjuries, Treasons, Homicides and Murdres, in shedding of Infants blood, with manie other Wronges, odious offences and abominacions’, which, while varied, is rather vague. Henry’s own mother had a servant loyal to Richard III in her household, and she praised him as a ‘true servant’ to his former master.7The main purpose of Henry’s first parliament was to attaint Richard III’s followers and reverse Titulus Regius, which had declared Henry’s future queen illegitimate.8Although Henry called Richard III ‘in deed and not by right king of England’ in the repeal of Titulus Regius, ten years after Richard III’s death Henry would have the following epitaph created for his tomb:

I, here, whom the earth encloses under various coloured marble,

Was justly called Richard the Third.

I was Protector of my country, an uncle ruling on behalf of his nephew.

I held the British kingdoms by broken faith.

Then for just sixty days less two,

And two summers, I held my sceptres.

Fighting bravely in war, deserted by the English,

I succumbed to you, King Henry VII.

But you yourself, piously, at your expense, thus honour my bones

And you cause a former king to be revered with the honour of a king

When [in] twice five years less four

Three hundred five-year periods of our salvation have passed.

And eleven days before the Kalends of September

I surrendered to the red rose the power it desired.

Whoever you are, pray for my offences,

That my punishment may be lessened by your prayers.9

Political motivations aside, this is still the official memorial sanctioned by the Tudor government, which legitimises Richard III’s titles and mentions his bravery. We have no evidence of Henry VII ever accusing Richard III directly of murdering his nephews, the 12 year-old Edward V and 9 year-old Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York. It simply cannot overlooked that infanticide would have been at the very core of any propagandistic agenda.

Perhaps a less well-known fact is that there were no ‘Tudor’ accounts of Richard III published in Henry VII’s lifetime, other than John Rous’ Historia regum Anglie (History of the Kings of England). The work was begun in Edward IV’s reign, and was intended to give the Edward information about kings and prelates who might be commemorated with statues in St George’s Chapel, Windsor. But it was not finished until 1486, and by that time dedicated to Henry VII, with a revised account of Richard III. It is Rous who wrote the ludicrous account of Richard III having spent two years in his mother’s womb, and born with a full set of teeth, and hair to his shoulders.10 No one in Henry VII’s lifetime, however, and no one in later Tudor writing, repeated this farce.

New governments always have, and continue to, defame the former, and Richard III’s government put out their own share of propaganda. Richard III’s Titulus Regius accused his late brother Edward IV of bigamy, declared his marriage illegitimate, along with Edward’s children, called Edward and his court ‘ungodly’, and accused Queen Elizabeth Wydeville of witchcraft. It will always remain a possibility that Edward IV carried out a pre-contract with Eleanor Talbot that invalidated his marriage to Elizabeth, although no concrete evidence has been discovered. However, considering that witchcraft was illegal and Richard III not only failed to pursue prosecution, but took great pains to come to agreements with Elizabeth later on and take on responsibility for her daughters, it is evident this was a politically- motivated fabrication to render the queen vulnerable, and, therefore, propaganda. It worked. Elizabeth Wydeville was a deeply pious queen who has been slandered as much as Richard III himself,11 often in Ricardian writing, and it was Richard III ’s government’s propaganda that has stained her reputation.

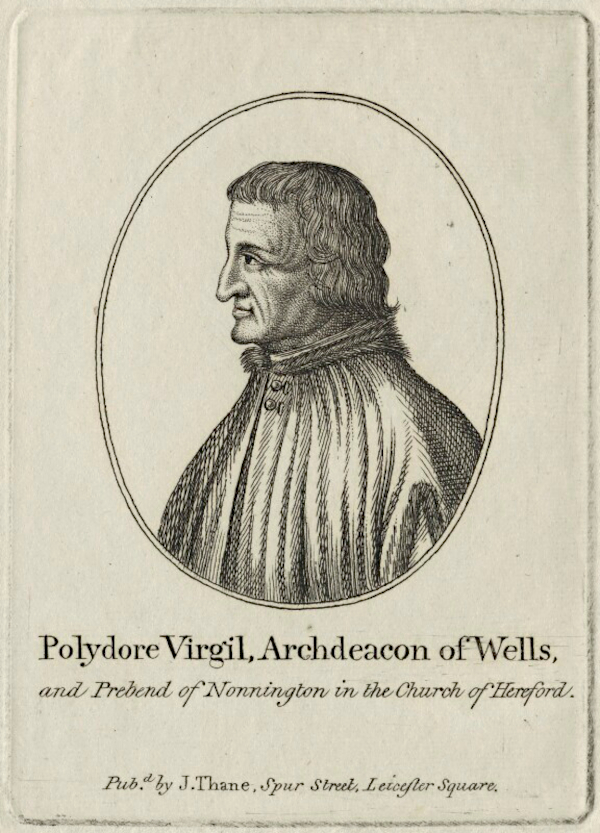

Wasn’t Polydore Vergil ‘Henry VII’s paid historian’?

The idea that Polydore Vergil was ‘Henry’s paid historian’ is completely misleading and lacks understanding of royal patronage. Propaganda is not put out by scholars working laboriously on manuscripts over years, although history can obviously contain propaganda. But Polydore Vergil was commissioned to write a history of England by Henry VII, not to write ‘Henry’s version of history’, but to write what would become the first modern history of England, paving the way for the later antiquarian movement which sought to contest imaginative chronicle histories like Rous’. The Ricardian idea of ‘Henry’s paid historian’ goes back to Clemens, as mentioned. Later in the 20th century The Betrayal of Richard III, V.B. Lamb claimed that ‘it is reported that the historian destroyed wholesale anything which did not agree with the version he wished to present, which was in effect the version acceptable to the Tudors. Whether this is true is uncertain, but bearing in mind Henry’s method of dealing with the Titulus Regius, it is at least possible.’12 Lamb fails to mention in the body of the text that Vergil’s biographer Denis Hay soundly debunked these claims, but does so in the footnotes. Lamb’s passage about Vergil begins by creating a tale about Henry VII, which follows “To the day of his death Henry’s hatred of his predecessor was undiminished. Richard had possessed two things which Henry never had – a sound title to the throne and the love of his subjects.’13 and is a fine example of 20th century Ricardian writing, in the fashion of Paul Murray Kendall, which purports to know Henry VII’s feelings. Much has been made of Henry VII ordering all copies of Titulus Regius destroyed in Ricardian writing, but generally by ignoring the fact that Henry was overly cautious because Edward IV’s succession had been destroyed by claims of invalid marriage and illegitimacy. Titulus Regius also obviously claimed Elizabeth of York was illegitimate, which technically barred her from marrying Henry. Henry went much further than just destroying Titulus Regius, he even secured a papal bull threatening to excommunicate anyone who questioned the legitimacy of his and Elizabeth of York’s children, as well as securing several dispensations to ensure the marriage’s validity could not be questioned. When seen in this context, it is perfectly obvious why he ordered copies of Titulus Regius destroyed. Those who find it so wildly unusual overlook the political theatre behind it as well.

Markham did not invent the rumours that Vergil had destroyed documents, those scurrilous claims were the result of anger at Vergil’s scepticism over English chronicles such as Geoffrey of Monmouth’s and dismissing England’s alleged first king Brutus, narratives we now understand as mythology. Henry Ellis wrote that ‘few writers of history have met with such harsh treatment,’ because ‘Vergil’s attainments went far beyond the common learning of his age’, and that ‘the earlier part of his history interfered with the prejudices of the English.’14 Some detractors dismissed Vergil as a ‘foreigner’, homo Italus, et in rebus nostris hospes, ‘an Italian man, and a guest in our affairs’. The anecdotes that are latched on to the most however, are John Caius’s, published in 1574, claimed that Vergil ‘committed as many of our ancient and manuscript historians to the flames as would have filled a waggon, that the faults of his own work might pass undiscovered.’, with La Popliniere, in 1599, adding that this was ‘by the King’s authority’.15 There has never been any evidence produced to back up these charges, and they are not corroborated accounts, merely one rumour repeated after the other with added flourish. They were also dismissed as early as 1636 by a William Burton in this interesting passage, which demonstrates the true influence Vergil had on the early modern historical writers. I have emphasised selected sentences:

[…]a work of great labour and like reading, but much carped at by John Druse* (who wrote a book against him), Jo. Leland, Richard White, Jo. Lewis, Humphrey Lluid, and others; not, as I conceive, for any just cause, but for that he, being an alien, should be graced with such a matter of charge, which most properly had belonged to a native of the land. The chief matters they charge him with are, first for that having taken the substance of the beginning of his History all out of the works of Geoffrey of Monmouth, yet unthankfully (imitating therein William of Newborough) lashing at him; next, for that in many places he pitcheth somewhat smartly upon the antiquity of Britain; thirdly, for that he doth seem severely to censure some of those Kings which he treateth of; lastly, that, having gotten many old manuscripts together, by whose help he compiled his book, after his conclusion of the same, he set fire on them all.For the first and second, it is well observed by many of great reading and judgment, that Geoffrey of Monmouth hath somewhat hyperbolically extolled the praise and antiquity of the Britons, and interlaced many passages of his own device, and drawn down a series of descents, but with what truth the just and true chronology of time, upon good examination, will soon discover; so that Polydore doth not upon the matter impeach the antiquity of Britain, but the fabulous inventions of the said Geoffrey. […] Lastly, for his destroying of manuscripts, I could never yet be drawn to believe it, neither is it probable, for that, unless he had had all the copies of each kind together, that by one act they might all have finally perished, he would never have attempted such an enterprize; and certain it is, by Leland’s Collectanea, that almost in every Abbey (himself setting down a catalogue of all manuscripts which he saw in each place) there was variety and store of copies, not only of the chiefest writers, but almost of the meanest chronologers and historians. But, whatsoever they have said, this I may truly say, and can make good, He was a man of singular invention, good judgement, and good reading, and a true lover of antiquities.16

The rumour that Vergil burned English manuscripts is directly connected to Vergil’s criticism of early English historical writing, and not to the alleged propaganda campaign against Richard III. The rumour, however, has been appropriated by Ricardian writers to try and prove Henry VII had documents destroyed to try and bury the legacy of Richard III.

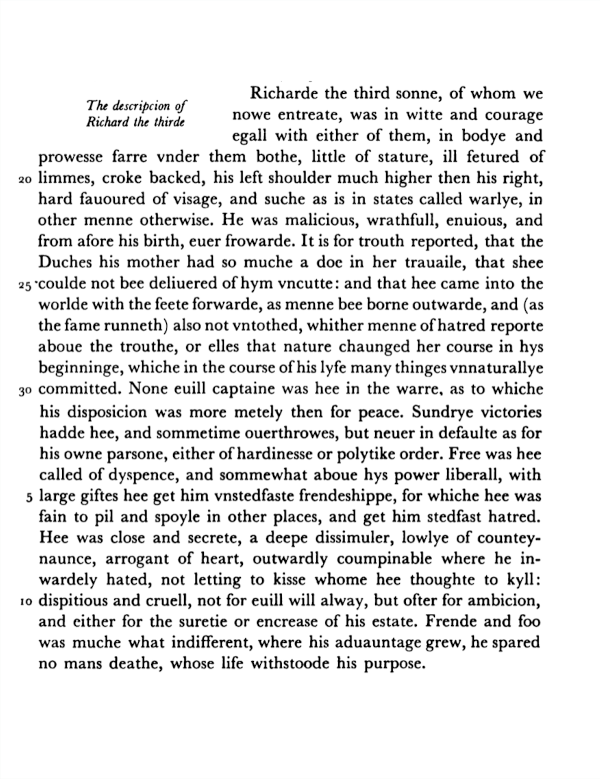

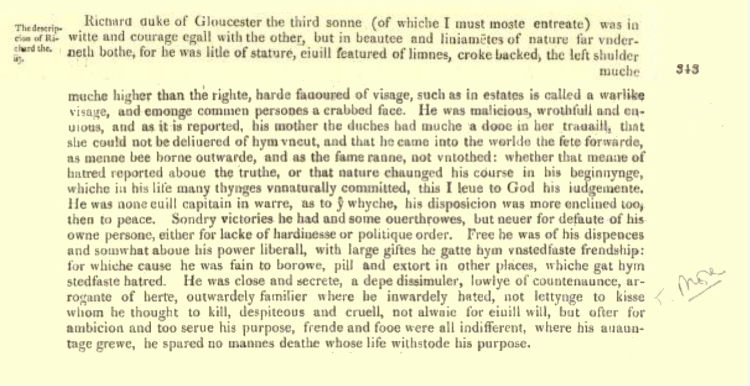

Was Thomas More’s writing Tudor propaganda in his History of Richard III?

If only I could dismiss Thomas More in the only sentence that his ‘History’ is deserving of: that is that is was not written as a history and was abandoned seventeen years before his death with no evident intention of publication. For centuries historians have taken More’s The History of King Richard the Third as an ‘official’ account of events, be it ‘propaganda’ or a reliable source. More’s History is neither. More himself never authorised its circulation.17 Despite this, it was published posthumously as an authoritative account by Grafton, then repeated almost exactly in Edward Hall’s Chronicles18. and Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicle,19 Shakespeare’s main sources. As you can see in the following excerpts the text is copied exactly:

Some scholars will point out that More did have access to reliable oral sources, various men and women who had lived through Richard III’s reign. That is probably correct, and it is what makes the manuscript a fascinating artefact, particularly as an oral history. But unless passages corroborate with other accounts, it should not be used as a source. More’s History has also been viewed as a humanist prose history, or a dramatic narrative. More’s literary influences including Suetonius, Tacitus and Sallust, Seneca, Plautus and Euripides, and the medieval mystery plays that More himself loved to write and act in as a young boy. It is sometimes viewed as an exemplum. Peter Ackroyd has suggested it ‘may have been the basis of exercises given to his own school or even to the boys of St Paul’s: there is a sudden reference to a ‘scole master of Poules” for no good reason.’20 Tyranny was a recurring theme in More’s work, and as Richard Sylvester points out ‘a subject for philosophical meditation as well as an ever-present danger in the kingdom.’21 However, none of this is significant when it comes to its veracity as a history, because the manuscript was never published. The fact is, that it is very dangerous to use an unpolished, unfinished manuscript, and not one unfinished at death, but untouched for seventeen years, and try to use this as evidence that Richard III murdered his nephews and buried them in the Tower of London, ‘at the stair foot, metely deep in the ground under a great heap of stones.’

This passage has been used as ‘evidence’ repeatedly, to the point where many readers do not know the whole of More’s story, which follows, that King Richard III: ‘allowed not, as I have heard, the burying in so vile a corner, saying that he would have them buried in a better place, because they were a king’s sons…Whereupon they say that a priest of Sir Robert Brakenbury took up the bodies again, and secretely entered them in such place, as by the occasion of his death, which he only knew it, could never since come to light.’

Because of More’s account, a pair of unidentified children’s skeletons reside in the Tower of London, in an urn, claiming to be ‘the relics of Edward V, King of England, and Richard, Duke of York.’

Read more about the Westminster Urn here.

Because More’s account is so imaginative, and has been so influential, it is usually considered propaganda piece. A less well-known fact is that Thomas More absolutely hated Henry VII and in a coronation ode for Henry VIII, he slandered the former king roundly, likening living through his reign to ‘slavery’.22 More was hugely critical of Elizabeth of York’s maternal family in his History, and eventually refused to acknowledge Henry VIII as head of the church, resulting in his own execution. Henry VIII, for his part, certainly wouldn’t have given a single thought to Richard III, let alone tried to maintain a propaganda campaign against him. It is simply not likely that More had any Tudor-biased antipathy towards Richard III, and his ‘history’ was a private project that was not meant to influence historians for centuries to come.

How historically accurate is the Tragedy?

The Tragedy is not historically accurate as we understand historical research now. It is true that the Antiquarian movement, which introduced critical evaluation principles in historical research, began in the Elizabethan period, but their work was often derided at the time. History was not a fixed term in the Elizabethan era, and historians did not practice the sort of research the 21st century historian does. ‘History’ was a term that applied to a broad number of texts including poems and plays.23 Chronicle plays echoed the patriotic and even jingoistic mood of the public in the wake of the defeat of the Spanish Armada. The victory increased the demand for already-popular historical texts, and studies have suggested nearly all literate English people were avid readers of history, regardless of religious or socioeconomic background. Most of these readers, especially Londoners, would have gotten their history from historical dramas by Shakespeare, Marlowe, Heywood, Jonson and others. Patriotism and moral edification placed literary and ideological concerns over accuracy.24 Shakespeare was writing a form of history as it was published and consumed in Elizabethan England. He also, contrary to popular belief, followed the historical chronicles available to him very closely. Most of Richard’s ‘crimes’ have historical sources. However, Shakespeare’s readers and audiences, as we will discuss later, would certainly have recognised the subtext of the play. The performance of the Tragedy in Elizabethan England had an entirely different resonance than it does today.

Why is it important to clear the Tragedy of the charges of ‘Tudor Propaganda’?

My argument against ‘Tudor propaganda’ does not seek to dismiss that Richard III has been unfairly treated by historians, he has, like many others before and after him. The main issue is that many fall into the trap of thinking Richard III was more unfairly maligned than other historical figures, and this is simply not the case. What is the first thing you think of when you hear the name Marie Antoinette? Let them eat cake. An entire life is reduced to a single sentence that she never actually uttered. With a dedicated historical society who has been unearthing new information about him for decades, Richard III has fared very well. The significant difference between Richard III and other historical figures is that Richard III has become a compelling figure in popular culture, due to the The Tragedy of Richard III. If not for the Tragedy, the Ricardian movement and the eventual formation of the Richard III Society may not have happened. After all, the first revisionist history of Richard III was written by George Buck, who was James I’s Master of Revels. Buck’s interest in Richard III was sparked by the fact that his great-grandfather John Buck supported Richard III at Bosworth and was executed and attainted after the battle, but he clearly would have been acquainted with the Tragedy, its printing history of six quartos before being included in the First Folio in 1623 a testament to its success.

In the 18th century, Colly Cibber’s adaptation and David Garrick’s portrayal of Richard as a clever but ultimately tragic villain stirred up a movement defending Richard III that attracted minds such as Mary Shelley and Lord Byron. That movement has lasted until this day. If there had been a propaganda campaign against Richard III, it actually failed. The defence of Richard III has been going on for four centuries. The absolutely spectacular pomp with which Richard III’s remains were reinterred in Leicester is evidence of this. Richard III has been immortalised, not by his historical self, or by his actions, but by his notorious fictional counterpart. To continue to attempt to reduce the play to ‘Tudor propaganda’ really does Richard III himself no favours, it merely leads to more argument about whether or not the Tudor historians were ‘right’. And we simply can’t appreciate the complexities of the Tragedy if we cling to the belief that Shakespeare created a set of complex histories merely to ‘flatter’ his monarch.

We use the Norton Critical Editions of Shakespeare’s texts.

Who Was Shakespeare’s King Richard III? series

Part Two: The Tragedy and Disability

Part Three: History and The Tragedy

.

.

.

- E. Burns, Richard III: Writers and Their Work, (Devon: Northcote House Publishing, 2006) vii. ↩

- Richard III Society The Ricardian Bulletin (06/21) 72. ↩

- C.S. Clegg ‘Censorship and the Problems with History in Shakespeare’s England’ in eds. R. Dutton, and J.E. Howard, A Companion to Shakespeare’s Works, Volume II: The Histories (Oxford: Blackwell 2003) 50. ↩

- Clegg ‘Censorship’ 50. ↩

- H. Walpole, Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of Richard the Third, ed. P.W. Hammond, (Gloucestor: Alan Sutton, 1987)107. ↩

- C.R. Markham, Richard III: His Life and Character Reviewed in the Light of Recent Research, digital edition, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1906) 173. ↩

- M. Axton & J. P. Carley, Triumphs of English: Henry Parker Lord Morley, (London: British Library, 2000), 262. ↩

- Richard III Society ‘Documents: Titulus Regius’ Richard III Society. ↩

- J. Ashdown-Hill ‘The epitaph of King Richard III’ Ricardian Bulletin (London: Richard III Society 2008) ↩

- A. Hanham, Richard III and his Early Historians: 1483-1535, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975),105. ↩

- A. Sutton & L. Visser-Fuchs, ‘‘A Most Benevolent Queen’: Queen Elizabeth Woodville’s Reputation, Her Piety, and Her Books’, The Ricardian, X:129, (June 1995), 214–245. ↩

- V.B. Lamb, The Betrayal of Richard III: An Introduction to the Controversy, (London: The History Press, 2015) 85. ↩

- Lamb, Betrayal, 84. ↩

- H.E. Ellis, Preface in P. Vergil Three Books of Polydore Vergil’s English History ed. H. Ellis (London: Camden Society 1950) xx. ↩

- Ellis, English History, xxviii. ↩

- Ellis, English History, xxiv. ↩

- R. Sylvester, Introduction in T. More, The History of Richard III and Selections from the English and Latin Poems, ed. R.S Sylvester (New Haven: Yale University Press 1976) ciii. ↩

- E. Hall, Hall’s chronicle : containing the history of England... (London : Printed for J. Johnson, 1809) ↩

- R. Holinshed, Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland: Volume 3, (London : J. Johnson 1808). ↩

- P. Ackroyd, The Life of Thomas More, Vintage 1999, p. 155. ↩

- Sylvester, History of Richard III, 15. ↩

- T. More, Coronation Ode of King Henry VIII, 1509, The Centre for Thomas More Studies. ↩

- Kamps, ‘The Writing of History in Shakespeare’s England’ in eds. R. Dutton, and J.E. Howard, A Companion to Shakespeare’s Works Volume II The Histories (Oxford: Blackwell 2003) 8. ↩

- Kamps, The Writing of History in Shakespeare’s England 4-5. ↩