Please watch:

Shakespeare the Author

One of Shakespeare’s most profound speeches doesn’t actually belong to one of his plays. The Strangers’ Case is the only extensive example of Shakespeare’s handwriting that survives, and it is from a passage in The Book of Sir Thomas More, a play penned by Anthony Munday. The Master of the Revels, Edmund Tilney, refused to allow Thomas More to be performed, likely considering the riot scenes it contains seditious. Shakespeare was one of several writers brought in to revise the play, but there is no evidence it was ever performed or published. The attribution of the unsigned speech to Shakespeare was suggested as far back as 1871. The identification of ‘Hand D’ as Shakespeare has been based on similarities to other extant handwriting, spelling, vocabulary, similarities in style and phrases in his other plays, and metrical tests. But the most telling is the group of academics who, in 1923, who suggested that Shakespeare’s ideals, his deep humanity, are what identified him as the author.1 Humanity is Shakespeare’s definitive trait. Even when buried deep inside one of his villains, it shines through.

The Strangers’ Case is one of my favourite examples to use when discussing authorial intent in Shakespeare, for the very reason that it does not belong to one of his plays. Shakespeare’s reputation, like most other historical figures, suffers from rather a lot of persistent mythology. The Richard III Society (of which I am a member) has been instrumental in perpetuating the mythology of Shakespeare as a ‘Tudor propagandist’, insisting that he wrote The Tragedy of Richard III to ‘please’ Elizabeth I, or that Shakespeare’s life would be endangered if he flattered her long-dead uncle. This less-than-credible an idea has become so pervasive it was mentioned on pop-culture website Buzzfeed as recently as last year.2 But even more sensible attempts to prove an alleged political orthodoxy in Shakespeare’s works unravel when you actually read the plays. There are far more insidious mythologies too, such as the authorship question, a silly conspiracy theory. Or the popular idea that Shakespeare was merely an ‘opportunist’ who churned out plays only for financial gain. As Lukas Erne writes: “Sidney Lee, in his influential biography, was instrumental in promoting the image of a Shakespeare unconscious of the quality of his work and largely uninterested in it beyond its “serving the prosaic end of providing permanently for himself and his daughters.” Many biographies have followed since, and a few have entirely endorsed Lee’s portrait of Shakespeare as a money grabber.”3 Most of these arguments are classist, of course, borne of the idea that a middle-class writer couldn’t possibly possess a talent like Shakespeare’s. They do, however, negatively influence both Shakespeare’s reputation, and our perception of his authorial intent.

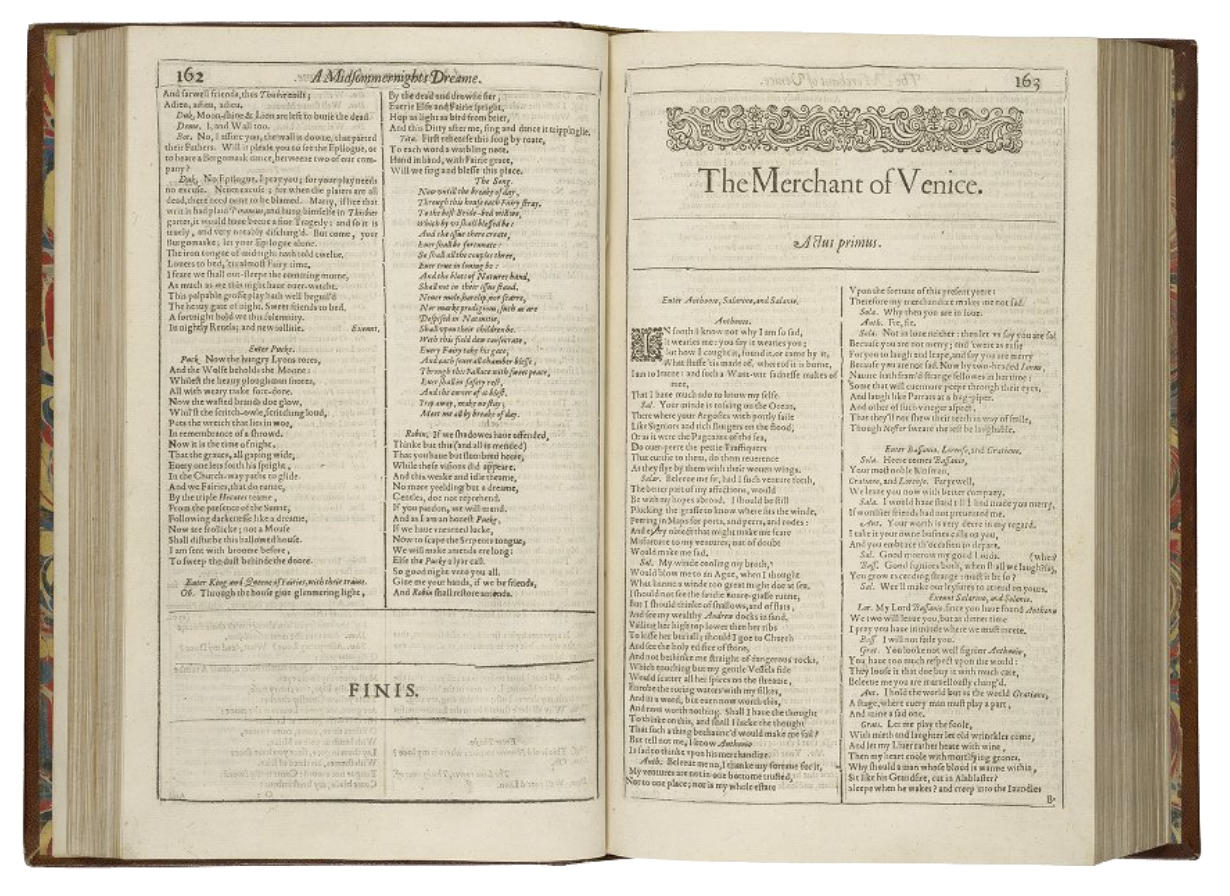

Another common misconception is that Shakespeare’s plays were written strictly for performance, therefore, the performances, and that is, interpretations by actors, take precedence over the text. Lukas Erne’s research has demonstrated that Shakespeare, in fact, wrote his plays with a view to printing them for public consumption. Merchant itself had three quarto publications. The quartos themselves were popularly thought of as ephemera for some time, but many quartos were bound into collections and have owners’ names recorded in them, indicating they were cherished items.4 Shakespeare was aware of his worth as a published author as well as playwright, and he catered to a well-off, educated audience, both as theatregoers and readers. Many 16th and 17th century playbooks have been found in collections of the middle classes and the nobility. Passages from playbooks were included in commonplace books and anthologies, and even discussed in a scholarship.5 We also know Shakespeare must have been revered enough in his time to warrant his friends producing the First Folio. Although all of Shylock’s lines in Merchant tend to be performed these days, other plays, with the Tragedy of Richard III being a good example, were rarely performed in full. The plays were, however published in full in the First Folio, indicating the full texts were reading texts.

So, how does this factor in to authorial intent? If we think of Shakespeare as an opportunist unconscious of the quality of his work, it changes the tone of his plays entirely. Shakespeare’s plays are very obviously not ‘churned out’. With the publication of the First Folio, we know Shakespeare had ‘full’ texts, completed stories, of each play. When discussing authorial intent in Shakespeare we should focus on those texts, and place them in their historical context. And when thinking about authorial intent, it is essential to think about all of Shakespeare’s work. Shakespeare is his entire ouvre. Shakespeare doesn’t write one play in which a man and woman fall tragic victims to racism and envy, and then mock Jewish people in another, or write pantomime villains with no complexities because he thinks his ‘head will be chopped off’.6 We can also trace Shakespeare’s own development as an author through his characters. So, if Shakespeare meant his plays to be read by his audience, then we know that every last sentence is important. Everything Shylock says must be taken into account. And even though he is ostensibly a minor character, Shylock has quite a lot to say to us.

Anti-Judaism in Medieval England

Abigail Graham’s upcoming production for The Globe will focus on “how white Christian men use their power to pit minorities against each other.”7 Why is Merchant so well suited to portray something we are really only becoming widely conscious of recently? The history of anti-Judaism in medieval England is far too vast for me to cover here, but, in essence, medieval England was one of the most anti-Jewish countries in Europe, with both economic and religious factors fuelling their hatred of Jewish people. There are often folkloric elements to prejudice, and the ‘blood libel’ fantasy, the false accusation that Jews murdered Christian boys to obtain their blood for religious ritual, began in England in the 12th century, and even made its way into Chaucer. The population of Jewish people in England was only around 3000, and the Christian population up to 3.7 million. Being such a tiny minority with different religious rituals obviously made them targets. The Catholic Church, of course, had a large role in anti-Judaism. Jews as well as Muslims suffered in the Crusades, the Christians fuelled by hatred against Jews as ‘killers of Christ’. We do often hear about the English hatred of usury, moneylending with interest, which could only be practised by Jewish people lending to non-Jews, but we don’t hear about how important Jewish moneylending was to the English economy. Jewish people were afforded some protection by the crown so the crown could continue to benefit financially through four major revenues: reliefs, comprising one-third of the estate of a deceased Jew, escheats, the reversion of Jewish held property to the state upon death, and fines and tallages (taxes). But of course, everyone needed access to loans, including the working classes.

We also don’t hear so much about the series of massacres between 1189 and 1190, that begun after Richard I’s coronation, which culminated in the horrific massacre at York. It began as a fire raged through York, and under its cover, nobles who who were in debt to Jewish moneylenders incited a riot, targeting Aaron of Lincoln’s property, killing Benedict of York’s widow and children, their home set alight while they were still inside. Soon enough the angry mob turned on all of the city’s Jews, demanding they be baptised as Christians, or be put to death. The Jewish community took refuge in the town’s castle, in Clifford’s Tower. While the murderous mob surrounded the castle, the 150 odd Jewish people trapped inside planned a mass suicide, encouraged by Rabbi Yomtob, a visiting rabbi from Northern France, rather than allow themselves to be forcibly converted. They set fire to the castle and many men slit the throats of their wives and children, so they would not suffer the sin of suicide, before being killed by Yomtob themselves. The next morning the remaining survivors threw themselves on the mercy of the Christians, pledging to be baptised. The Christians murdered them in cold blood.8 The site was not memorialised until 1978.

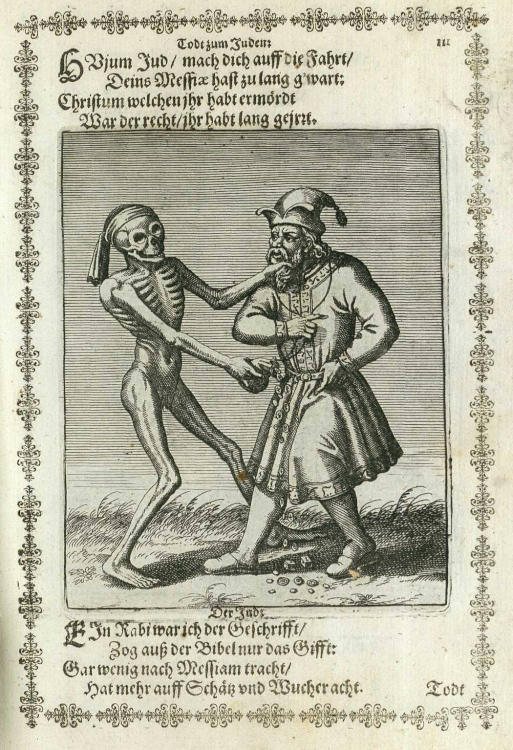

In 1215 a decree was passed by the Catholic Church forcing Jewish people (and Muslims) to wear an identifying badge. England was the first to enforce it, and the most enthusiastic. In 1255, the ‘blood libel’ fantasy still holding fast, 9 year-old Hugh of Lincoln’s accidental death sparked ritual murder accusations that resulted in the slow and horrible hanging execution of nineteen Jewish people, with a further ninety-one Jews were imprisoned.9 By 1275 English laws banned usury, moneylending, and segregated Jews, decreeing they could no longer live in close quarters or socialise with Christians. In 1290, Jewish people were expelled from England altogether. The property of the 300 Jews who were hanged went to the Crown. It would be almost four hundred years before they were allowed to return.

Had Shakespeare Even Met a Jew?

Something you will hear frequently is that Shakespeare had probably never met a Jewish person in his life, because all the Jews were expelled from England at the time. There were, in fact, Jews who had converted to Christianity living in England in Shakespeare’s lifetime, just as there were converted Catholics. Admittedly, the recorded number of Jewish people living in England was very small, and there were probably only up to a couple of hundred Jewish people at a time in the country.10 The term ‘Marranos’ was used to describe Jews who had converted to Christianity to avoid persecution, but practised their faith secretly. There were also practising Jews in London, a small Portuguese Marrano community that numbered around 90 and included physicians and merchants. 11 This community included the doctor Roderigo Lopez, physician-in-chief to Elizabeth I, notoriously executed for allegedly plotting against her. At the scaffold, Lopez tried to make a Christian end by professing that he “loved the queen as well as he loved Jesus Christ”, which apparently “moved no small laughter in the Standers-by”. Stephen Greenblatt suggests that, as Merchant was written in the wake of Lopez’s death, Shakespeare was ‘both intrigued and nauseated’ by the crowd laughing in the face of a man who was about to be hanged, drawn and quartered in front of them.12

There is reasonable evidence that Shakespeare encountered a Jewish community in Houndsditch, where he lived until 1596. Market stalls and shops were set up against the walls of the Dolphin Inn in Houndsditch, along with a metal foundry and ‘many shops for brokers, joiners, braziers and such as deal in old linen clothes and upholstery’.13 The Jewish immigrants sold second-hand clothing and traded as pawnbrokers, the same professions Jewish people were restricted to in renaissance Venice. It is thought Merchant was written between 1596 and 1599. It is reasonable to suggest that Shakespeare at least spoke with some of the Jewish traders, if not extensively. Professor Shaul Bassi writes that ‘The relationship between Shylock and the other characters is clearly based on a very intimate understanding of the new social configurations created by the Ghetto’. 14 So it seems that Shakespeare’s Venice and its Jews were not simply products of his imagination.

The Jewish Moneylender

The medieval association of Jews with greed has had a lasting effect. Its roots are in the practise of ‘usury’, lending money at interest, which was tightly regulated in the middle ages, and frowned on by the church, but not totally forbidden, contrary to popular belief. Jews were, according to their scripture, permitted to lend at interest to non-Jews. But Christians did also lend at interest, although it was sometimes couched as fees, and they charged mostly around 5%, but up to 10% in some cases. In Italy, pawnbroking, now considered somewhat sleazy, was created by Franciscan preachers who wanted to ban Jewish moneylending from towns. Pawnbroking, selling used clothing and linen, and moneylending, were the main areas of employment or business available to Jews in renaissance Europe. Shakespeare’s own father was accused of usury, and Shakespeare himself was involved in at least one recorded transaction with a Stratford citizen.15 As Francis Bacon wrote, ‘to speak of the abolishing of usury is idle. All states have ever had it, in one kind or rate, or other. So as that opinion must be sent to Utopia.’16

The Monte di Pietà, still in operation today, never really competed with Jewish moneylenders. Their loans were capped, and, for larger sums, people turned to Jewish lenders anyway.17 Jewish moneylending was an important part of the economy. Although having a Jewish lender available was generally justified by “the financial distress that the paupers experience because of the absence of a Jewish lender”,18 Jewish lenders also furnished wealthy merchants, landlords and the Italian governments themselves. Dowries seemed to be a popular reason for Jewish lending, with the highest percentage of household loans going to those with daughters.19 And, of course, the governments taxed jewish lenders heavily, with Maristella Botticini proposing that “town governments were, in effect, taxing their own citizens when they established local monopolies in Jewish lending, allowed the Jewish incumbent to charge high interest rates, and then taxed away part of the ensuing rent.”20

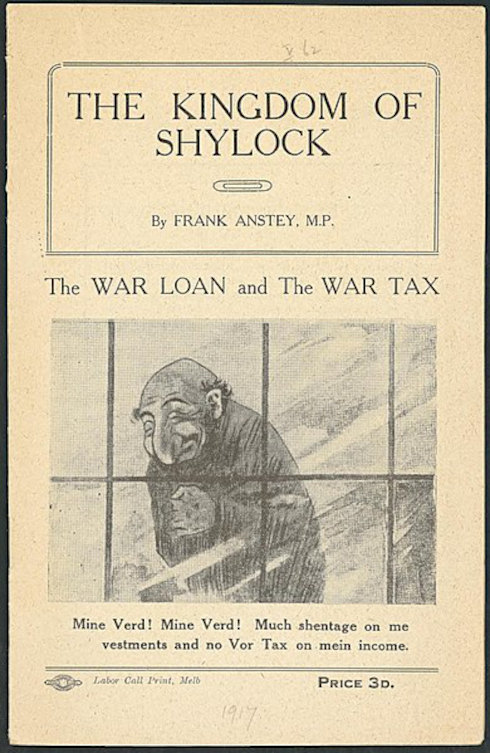

The fact that usury was not actually ‘banned’, but merely practised under strict regulations, demonstrates the hypocrisy meted out by Christians when it came to their supposed distaste for the Jewish person’s ‘greediness’, and it is this very hypocrisy that Shakespeare exposes in Merchant. Shakespeare’s sources contained a truly medieval conception of Jewish people, particularly the moneylender. Merchant has long been accused of being anti-Semitic and Shylock has long caused anxiety in Jewish audiences. At some point, the terms “Shylock,” and “shylocking” entered the English language as synonyms for loan sharks and their practices, although this was mostly prevalent in the United States.21 So we may fall into the trap of thinking Shakespeare depicted Shylock as a moneylender to perpetuate a particular stereotype, but that is based on our idea of the stereotype. Shakespeare’s only Jewish character was portrayed a moneylender because that is the trade many Jews engaged in at the time, and Shakespeare’s main source featured a merchant borrowing from a Jewish moneylender.

As Shakespeare enthusiasts will know, plays were often adapted from other plays, and other sources. The Three Caskets is an ancient tale, which Shakespeare would have read in Gesta Romanorum, a collection of moral tales probably intended for sermons. Bookseller and antiquarian John Fry, in the 19th century, suggested Alexander Silvayn’s Orator of 1596 as a source, which includes the ‘Story of a Jew, who would have a pound of a Christian’s flesh for his debt’, and John Gower’s epic Confessio Amantis, 1483, which includes the casket-choosing plot device.22 Merchant was mainly adapted from the Italian novella Il Pecorone, which provided most of the romantic comedy elements of the story, the rich heiress to be won, the pound of flesh bargain, the heiress coming to the rescue of her lover’s friend in the court case, or uncle, in this story. But Il Pecorone features an unnamed Jewish moneylender who had no motivation to harm the merchant character other than ‘so that he might boast that he had slain the chief of the Christian merchants’.23 Shylock, as we will discuss further, has rather a lot more motivation than that. A Christian man has abducted his daughter; according to both Venetian and English laws at the time, elopement, marriage without permission of the family, was an abduction. An abduction, even with both parties’ consent, was legal rape. Historian Brian Pullan has found another fascinating possible historical source:

“lurking in the rule book of the Venetian magistracy which dealt with usury is the record of a dubious three thousand ducat loan, giving rise to a case tried in 1567–8 and involving an elderly Portuguese Marrano. His miserly and cantankerous character, expertise with jewellery, and loveless relationship with his daughter and servants are strangely evocative of Shylock. One of the porters of the Venetian ghetto in 1589 happened to be called Gobbo and had a son Tonin, a young Gobbo in the same occupation; both were witnesses in an Inquisition trial of 1589 of a young man, a kind of proletarian Lorenzo, who courted a Jew’s daughter (a Rachel, not a Jessica) and unfortunately failed to convince the tribunal that he had honourable intentions of converting her to Christianity.”24

Looking at the sources used for Merchant, it becomes more apparent that Shakespeare’s choices for Shylock, and Shakespeare’s conception of a Jewish person, were driven by empathy. As Michael Shapiro writes, “Shakespeare essentially superimposed more modern conceptions of the Jew on traditional medieval stereotypes, thereby creating a rich and not always consistent matrix of details.”25 The difficulty in Merchant is that Shylock’s tragedy is told within a comedy. But it is not concealed. Shylock’s tragedy is not a modern reading of Merchant, it has always been there, and on some level, I think we know it has always made someone, somewhere, uncomfortable, questioning, sympathetic.

Who is Shakespeare’s Shylock?

The world had undergone vast changes between the medieval and early modern period, and Shakespeare lived in a time of increased globalism. As Stephen Greenblatt points out, “the entire Elizabethan book trade, was conspicuously international. The reading public, by modern standards, may have been fairly small, but its interests were strikingly cosmopolitan.”26 So Shakespeare had probably not only met Jewish people, but read about them, and read about Venice. Shaul Bassi even imagines that Shakespeare may have visited Venice.27 Perhaps, probably, as a history enthusiast, Shakespeare had read about the horrific English massacres of Jews, about their struggles in England, certainly he would have read about their exile. Perhaps Shakespeare read about the harrowing suicides at the York massacre, and thought about that as Shylock was forced to convert to Christianity. Perhaps he thought about Catholic friends forced to play the Protestant, or the Jews selling clothing from stalls on the roadside while they kept their faith secretly.

Shakespeare did not mention the Venetian ghetto in Merchant. Venetian Jews had been moved there in 1516, and Jewish refugees from Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and the Ottoman Empire continued to migrate there. While Jews were allowed to practise their faith, they were forced to were identifying yellow badge when out in daylight, and the ghetto gates were locked at night and patrolled by Christian guards. But Shaul Bassi desrcibes the ghetto as:

a place of incredible cultural vitality. From here Jewish learning reached Henry VIII seeking opinions on his divorce and the Rabbis of Amsterdam trying to establish a new community; it reached local Christian printers who produced one third of all the Hebrew books printed in Europe up to 1650 (including the first Talmud) and influential thinkers such as Paolo Sarpi and Jean Bodin. Once again we may imagine Shakespeare listening to a sermon by Rabbi Leon Modena, a myriad-minded man who in his celebrated autobiography Life of Judah listed teaching, preaching, writing poetry and music among his 20 or so occupations and gambling as the activity that bankrupted him.28

What did Shylock lose, then, when his Jewish identity was snatched from him? Shylock’s official role in Merchant is, in the frame of the comedy, as the obstacle to two young lovers, his daughter Jessica and her Christian suitor Lorenzo. Shylock is not, as the mistake is almost always made, the merchant, that is Antonio. But in Merchant, nothing is as it seems. We often question if Shylock is really a villain. But is Portia really a heroine? Or is she the obstacle to Antonio and Bassiano’s love? How do we triumph in her triumphing over her father, the obstacle to her love, with his casket test, when we know her suitor is a gold digger? But then, Portia is both racist and a hypocrite, incapable of meting out the mercy she espouses. Should we really feel pity for Antonio the Jew-hater, who spits on Shylock in the street, but is happy to use Shylock when he needs him, all the while showing him contempt? We may think that Shylock was not meant to become the focus of The Merchant of Venice, with its messy hilarity and concurrent romances. But as we delve further into Merchant, it seems that Shylock was always meant to be the secret heart of this story.

Featured image: © The Globe. Jonathan Pryce playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice (2016).

In our next article on The Merchant of Venice we will take a closer look at Shylock’s narrative throughout the text.

- W.W. Greg ed., Shakespeare’s Hand in the Play of Sir Thomas More, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1923), 5-6. ↩

- A. Ziegler ‘21 Things I Learned This Week That Truly And Honestly Made Me Say “Wow”’ Buzzfeed, May 22 2021. ↩

- L. Erne, Shakespeare as a Literary Dramatist, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 27. ↩

- Erne, Shakespeare as a Literary Dramatist, 36. ↩

- Erne, Shakespeare as a Literary Dramatist, 4. ↩

- paraphrasing actor Robert Lindsay from an interview in The Ricardian Bulletin: The Magazine of the Richard III Society September 2021 (London: Richard III Society 2021) 72. ↩

- A. Saville, ‘From The Merchant of Venice to Romeo and Juliet, how do we make Shakespeare less terrible in the 21st century?’ Evening Standard, Feb 16 2022. ↩

- S. Watson, ‘Introduction: The Moment and Memory of the York Massacre of 1190’ in Christians and Jews in Angevin England (ed) S. Rees Jones, S. Watson, (York: Boydell & Brewer; York Medieval Press, 2013). ↩

- J. Haidee Lorrey, “Hugh of Lincoln (St Hugh of Lincoln, Little St Hugh, c. 1246–1255), supposed victim of crucifixion.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. ODNB Online ↩

- J. Shapiro, Shakespeare and the Jews (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016) 76. ↩

- J. Shapiro, Shakespeare and the Jews, 72. ↩

- S. Greenblatt, Will In the World, (London: Jonathan Cape) Chapter 9. ↩

- M. Wood, In Search of Shakespeare (London: BBC Books, 2015) 193. ↩

- S. Bassi, ‘The Centuries-Old History of Venice’s Jewish Ghetto‘, Smithsonian Magazine, Nov 6 2015. ↩

- Greenblatt, Will in the World, 333-334. ↩

- F. Bacon, ‘Of Usury’ in Essays: Of Counsel, Civil and Moral, (Auckland: The Floating Press, 2014. ↩

- Maristella Botticini, A Tale of “Benevolent” Governments: Private Credit Markets, Public Finance, and the Role of Jewish Lenders in Medieval and Renaissance Italy’, The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 60, No. 1 (2000) 173. ↩

- Botticini, “Benevolent” Governments, 173. ↩

- Botticini, “Benevolent” Governments, 177. ↩

- Botticini, “Benevolent” Governments, 182. ↩

- E. Nahshon ‘The Anti-Shylock Campaign in America ‘ in In Wrestling with Shylock: Jewish Responses to The Merchant of Venice, (eds) E. Nahshon Jewish, M. Shapiro, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017) 34. ↩

- S, Kells, Shakespeare’s Library: Unlocking the Greatest Mystery in Literature, (Melbourne: Text House Publishing, 2018) 132. ↩

- Translation by William Waters, 1897, in J. Pendergast, ‘The Merchant of Venice’ in Shakespeare’s World: The Comedies, (California: Greenwood, 2019. ↩

- B. Pullan , ‘Charity and Usury: Jewish and Christian Lending in Renaissance and Early Modern Italy;, Proceedings of the British Academy, 125, 19–40. © The British Academy 2004. ↩

- M. Shapiro, ‘Literary Sources and Theatrical Interpretations of Shylock’ in Wrestling with Shylock: Jewish Responses to The Merchant of Venice, (eds) E. Nahshon Jewish, M. Shapiro, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017) 14. ↩

- Greenblatt, Will In the World, 333. ↩

- S. Bassi, ‘The Jewish Quarter‘, The Globe Blog, March 2 2022. ↩

- Bassi, Jewish Quarter. ↩