A Hard Day’s Night – Head – Catch Us If You Can

The formula of the pop idol movie is something we are probably most familiar with from the films of Elvis Presley or Cliff Richard. Essentially the teen idols portray a fictionalized analogue of themselves; talented but regular guys with names like Don or Walter or Larry, whose aspirations to musical success are tempered not by the egotism of the star, but the admirable qualities of very ordinary guys. They have no thoughts of fame or fortune, they only want to work on vintage cars, or travel across Europe with their companions, or fight against dodgy boxing promoters or crooked land-developers, meet the right girl, and occasionally burst into song and dance numbers. The musical numbers are never a product, deliberately placed, they erupt out of the story, out of the lives of the characters. Spontaneously bursting into choreographed song and dance numbers expresses a mindless joie de vivre, convincing us these are troubadours, not manufactured pop idols.

A Hard Day’s Night

Starring The Beatles

Directed by Richard Lester

Written by Alun Owen

Produced by Proscenium Films

Released July 6 1964

A Hard Day’s Night was The Beatles first film, produced at the height of Beatlemania. It presents a fictionalized day in the life of the Fab Four, as they travel from Liverpool to London to perform some numbers for variety TV show. On the surface there is nothing subversive about it. Fatuous, frivolous and silly, John, Paul, George and Ringo goof their way through, quipping flippantly, with Wilfred Brambell (comic and character actor best known for his eponymous role in Steptoe & Son) in tow playing Paul’s rascally Grandfather.

The lads from Liverpool play caricatures of themselves, barely more complex than the characters in the later cartoon series. They defy their record company management, give cheek, escape relentless teen fans, brutal in their devotion, sass London’s media sophisticates, Norman Rossington as their manager in a peculiar note threatens to tell people what John is really like, while Ringo, the sensitive one, disappears before the gig on a soul searching walking odyssey of London, the others go to find him, everyone is pursued by police in a chase clearly in the Carry On tradition, there’s no plot and little point, other than a series of comedic bits, and perhaps a sublte satire on the Beatlemania phenomena and The Beatles themselves. When it comes to the music all pretense falls, it is authentically felt, pure-hearted pop poetry.

Despite Oscar nominations for Alun Owens script and a frenzied box office, the film has sometimes been panned as one of the worst ever made, frivolous pap, little more than a marketing exercise. Film historian Stephen Glynn in The British Film Guide said it was made as a “low-budget exploitation movie to milk the latest brief musical craze for all it was worth.” It turned out to be a whole lot more.

While seeming flippant, A Hard Day’s Night did more than invent the music video. It turned the pop film genre on its head; from real situations, with outlandishly fake songs, to fake situations with heart-breakingly real musical performances.

Richard Lester went on to make The Beatles’ second film, Help! a year later, several quintessential 1960s sex comedies, the oddball anti-war film How I won The War that starred John Lennon, Spike Milligan’s post apocalyptic absurdist comedy The Bedsitting Room, the magnificent 1973 production of The Three Musketeers, the perhaps less well received, but no less irreverent sequels to Superman, and many others, and in 2006 was awarded an MTV Award for his pioneering multi-camera, multi-angle technique, used in A Hard Day’s Night; essentially he invented the modern music video.

In 2014, on the film’s 50th anniversary, a fully restored print, with a completely re-worked soundtrack, has been released. The editors at The Criterion Collection sought out the original tapes from Abbey Road studios, even the original sound effects; you can read more about their process in this interview in Rolling Stone.

Re-worked to original specifications but in incredible 5.1 stereo sound, the restored version has seen people queuing in the streets to catch the film in theatrical release, and topping the charts in iTunes/Apple TV sales and rentals. More than a curiosity, more than nostalgia, looking again at the seemingly ingenuous film reveals a buoyant energy, a spirit of playful irreverence and open-hearted discovery, something joyously unsophisticated, something very rock ‘n’ roll, it seems we, and music, may have lost.

Head

Starring The Monkees

Directed by Bob Rafelson

Written by Bob Rafelson and Jack Nicholson

Produced by Raybert Productions

Released November 6 1968

Head ends where it begins; traffic, officials, dignitaries, media, soldiers, and fat cops mill about, readying for a ribbon cutting ceremony. Through an echoing insistent alarming soundscape Micky, Peter, Davy and Michael burst through the ribbon, pursued by an unknown and strident chaos. With bells tolling they leap off the newly built bridge and plunge into the soothing embrace of a soporific psychedelic ocean, a colourful balm inhabited by mermaids, Carol King and Gerry Goffin’s Porpoise Song, sung by The Monkees, a submerged dream of echoing Hammond organ, church bells and orchestral strings. What lies in-between beginning and end is a surreal exploration of their imaginary pop reality as The Monkees. Their leap into the psychedelic an escape from the artificial into the real. Like the TV series head uses the same kind of non-linear, avant-garde cuts and jumps as the TV series. In antithesis to the comic juvenalia of the TV series, we cut to a scene where the gorgeous Mireille Machu kisses each of the boys in turn to see who is best; at once innocent and incredibly suggestive. It segues to black and clips of the Monkees appear in TV screen shaped boxes, and we hear the comic refrain, “Hey hey we are the Monkees, you know we love to please, a manufactured image, with no philosophies…you say we’re manufactured, to that we all agree, so make your choice and we’ll rejoice in never being free, Hey hey we are the Monkees, we’ve said it all before, the money’s in, we’re made of tin, we’re here to give you more, the money’s in we’re made of tin we’re here to give you more…” the last TV screen appears and shows the brutal, iconic clip of South Vietnam’s Chief of National Police executing Nguyen Van Lem, a handcuffed suspect, in the street. There’s a shot and a scream. A screaming fan. Images of fans screaming and the Monkees getting ready for a concert merge into newsreel cuts of warfare, artillery, bombing. A comic war scene in the style of the TV show segues into a concert performance of the Mike Nesmith song Circle Sky –

Circle sky

Telling lies

Here I stand

At demandAnd it looks like we’ve made it once again

Yes, it looks like we’ve made it once again

Images of screaming fans are cut with scenes of Vietnamese women and children crouching in fear, pretty American girls, B&W cuts of civilians crouching, running in a powerful expression of terror, regret and irony. Screaming fans rush the stage and the band are torn apart in effigy. That scene merges with clips of salesmen declaring the world’s largest Ford dealership, and Ronald Reagan being bellicose on the Gulf Of Tonkin, clips from old Bela Lugosi movies, Micky Dolenz lost in a desert, random vox pops. Conflating the fake with the real, the story with the truth, the lie with the truth, they go on to dismember their former image in a series of scenes, like those of the TV show but twisted, seeking escape from the cliched milieu of TV situations. After, back, before, time and narrative causality are all a jumble in Head, they are given a tour of a facility half Bond parody super-villain lair half box factory, where small peculiar things just go wrong. They are dandruff on Victor Mature’s head, vacuumed up, trapped in a box, a Dali-esque bathroom, a garish B movie castle, back in an iron box, back in the studio backlot reality.

Bob Rafelson originally pitched the idea for The Monkees, a TV show about an aspiring band, unsuccessfully, in 1962. Undoubtedly at the stage it would have been more in the Cliff Richard or Elvis style of musical show, perhaps something like the 1961 film The Young Ones. The success of A Hard Day’s Night undoubtedly influenced producers at Screen Gems decision to give it the go ahead and more importantly the irreverent attitude of the show.

Some attribute Head with the end of The Monkees as a band, it was both too political and too weird for their former audience of 60s tweens, and that very commercial stardom made it unappealing to the burgeoning antiwar flower-power generation they were addressing, but as symbolised by the leap from the bridge, their career as manufactured teen pop idols was undoubtedly already over.

Peter Tork said last year in the Hollywood Reporter he still doesn’t quite know what Head was about, that it seemed to say we’re all trapped in the box, and no one can get out, a message he disagrees with. It’s an exploration where many of the parts seem spurious, obtuse, surreal or simply comic, but it is also one of the few films where the disparate parts actually add up to more than their sum. Out of the manufactured world, the parody of the idol, the pulp backlot TV reality of the 60s, out of the cliched narrative of heroes and villains, of westerns and war shows, suddenly the music emerges, preternaturally real.

Bob Rafelson and Jack Nicholson went on to make other iconic films of the American counter culture, Easy Rider and The Trip. Dennis Hopper starred in both of those films, and appeared in a brief cameo in Head, as did Nicholson and Rafelson themselves, along with Frank Zappa and many others. Looming over them all the literally giant sinister figure of Victor Mature, half comic gangster, half western hero, a paranoia inducing symbol of the old order. It was the money made from The Monkees that allowed Rafelson to form BBS Productions with Steve Blauner and Bert Schneider, and they went on to make other films in the studio system but with an independent spirit informed by the counter-culture movement. Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, The Last Picture Show, Drive He Said, A Safe Place, The King Of Marvin Gardens, all of which are available from Criterion in the America Lost And Found box set, featuring new restored high-definition digital transfers, 5.1 channel sound, and numerous extras, behind the scenes pieces, documentaries and interviews featuring The Monkees, Jack Nicholson, Bob Rafelson, Peter Fonda, Peter Bogdanovich, Tuesday Weld, Bruce Dern, Laszlo Kovacs exploring the era, the BBS phenomena, the counter culture and the new American film making scene.

The Monkees naive take on reality lost some impact in the 70s, as their audience and the world lost some of that sense of hope and innocence and grew a little more cynical. In the 70s and 80s Head showed in indie theaters alongside films like Hair, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, Koyaanisqatsi and Eraserhead. The Monkees achieved something remarkable, from being manufactured pop idols with nothing to say but frivolities, by parodying themselves they became a real band, with a philosophy, with something important to say. Re-runs of the TV show in the late 80s saw The Monkees gain a whole new audience, and re-capture the interest of their legions of original fans – and they’ve been touring ever since, with occasional line-up changes. They don’t only play hits like The Last Train To Clarksville, they don’t only appeal to nostalgia, they play clips and songs from Head in their live shows, maintaining the counter-cultural, the political, the surreal, the subversive edge they achieved with Head.

Catch Us If You Can

Starring The Dave Clark Five

Directed by John Boorman

Written by Peter Nichols

Produced by David Deutsch Productions

Released April 1965

Half way through the shooting of the last commercial for a half a million pound meat marketing campaign “Meat Is Go!”, the young starlet, Dinah (Barbara Ferris) who says she has just bought an island, and a nobody stuntman, Steve (Dave Clark), run off together in the latest E-Type Jag stolen from the set. still wearing their burglar costumes, they go searching for metaphorical islands in London in winter. Scuba diving in a pool, an orange tree growing in a hothouse in Syon Park. They are pursued by the police and hired goons put into play by Leon Zissell, the Machiavellian head of the Ad company and his Meat Promotion Council cronies.

There is no breaking spontaneously into song and dance out of joie de vivre here. Although billed as a comedy this is a serious drama exploring youth, folly, love. When it was made The Dave Clark Five were as popular as The Beatles. It opens with a soundscape as the lads, living in a converted church in London, are woken up the distorted harmonics of the church organ, which merges into the title track. They get ready to go to work as stunt men and extras, after a bit of banter they head off through the streets of London. The instrumental track On The Move plays, all raw muddy saxophone, and jazzy, jungly drums. This is no pop treacle. Around the streets in an extraordinary montage they pass giant cut outs and posters and billboards of Dinah’s face, Dinah leaping, Dinah flying through the air – the lads pursuing her, all with the slogan, “Meat For Go!!”

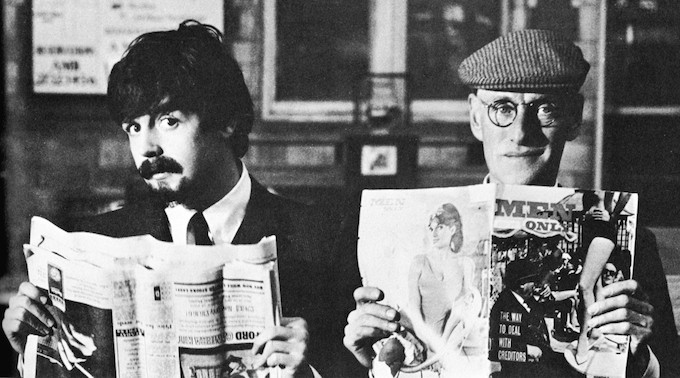

Right on the cusp of when everything changes, in black and white when the world has already started exploding into colour, seeming sophisticated and modern before the world descends into farce. There is no parody, not even self parody. The style is part Ealing Studio drama, part Ken Loach social realism. On the run, they stop in some derelict buildings inhabited by hippies and ravers, and are forced to flee when the place is attacked by infantry and tanks. The car takes a direct hit, and Dinah and Steve run as the army rounds up the young tribe of travellers. Meanwhile the Madmanesque establishment figures, manipulators in thick spectacles and three piece suits sit around smoking cigars and drinking scotch in their ultra modern high rise offices, chuckling smugly at quips about how advertising is total war, while plotting the public capture of our young lovers on the run. Obsessed with his young starlet, Zissell has also implied to the papers that Dave is dangerous, that he has kidnapped Dinah.

They continue their odyssey, and decide to head to Dinah’s island, and are picked up and taken to Bath by a pair of somewhat frustrated and acerbic wealthy eccentrics, Lenny and Nan (Robin Bailey and Yootha Joyce). Avuncular Lenny shows Dinah his collection of defunct stereoscopes, photographic and cinematic devices, a collection that embodies “the desperate measures people take to immortalize the moment” and, in the face of age, of decay, by contrast, the callous hopefulness of youth. When the rest of the crowd arrive, cougarish Nan costumes everyone as old Hollywood stars from her collection of vintage clothes, and they head off to the Arts Ball party at the Roman Baths.

From the bizarre Meat For Go!! montage, to the Army attack at Salisbury Plain, to the exuberant costume party and chase at the ancient Roman Baths, crossing to Burgh Island in a raised motorized tractor carriage, Catch Us If You Can is filled with both the energetically surreal and moments of poignancy. The Dave Clark Five’s music as soundtrack, at times invigorating, or melancholy, unlike Head or A Hard Day’s Night, never breaks through as part of the story or as performance, nevertheless, the vigour of the title track as the chase intensifies, the reflective tones of When as Steve and Dinah flee through wintry landscapes toward a refuge in Devon, is never garish or obtrusive, it somehow embodies the scene and the moment perfectly.

Their refuge proves a disappointment – Steve’s old mentor barely recognizes him, and instead only sees how the famous “butcher girl” could help to publicize his own schemes. Finally arriving at the island, Zissell is there before them. Running away has achieved little, except huge publicity for the campaign, and after everything Dinah goes back to her empty life as a starlet, her life as a property, with Zissell to Meat For Go!!

Peter Nichols began as an actor in a Combined Services Entertainment Unit in Singapore, entertaining troops along side John Schlesinger, Stanley Baxter and Kenneth Williams, but he is mostly known for plays, including A Day In The Death of Joe Egg, The National Health, Privates On Parade, Poppy and Passion Play, often combining intense drama with comedic techniques from vaudeville, music hall or pantomime. The conventional narrative of Catch Us If You Can owes more to his earlier work writing for TV.

John Boorman went on to make, amongst others, the over the top acid induced sci-fi fantasy, Zardoz, with Sean Connery as a moustachioed, loincloth sporting, shot gun wielding barbarian destroying the Utopian dreams of jaded immortal sophisticates, and Deliverance, another story filled with intense moments exploring a clash between the urbane, the civilized and the raw, the primitive.

Catch Us If You Can with its critique of the person as product, its imagery presenting the surreality of the everyday, its tale in which no one bursts into song, its de-idolized pop idols, exploring weakness, selfishness, disillusion, in a story that ultimately results in empty-hearted disappointment, in which the villain wins, and love is shallow, turns every convention of the pop idol movie inside out. Of course these intense issues are handled with a light touch, a sense of humour, a very British resignation. While it may seem light, in the context of the genre it’s a remarkable experience, its tale of youthful disillusion and disappointed love almost archetypal. There would be nothing else comparable until Quadrophenia, based on The Who album, some 14 years later.