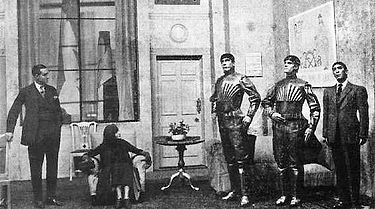

The term ‘robot’ was coined in 1920 in the play R.U.R. – Rossum’s Universal Robots, by Czech playwright Karel Čapek. The science fiction story dealt with themes we still find in SF today, of an artificial humanoid underclass, which eventually rises up, wiping out their human masters. Unlike the majority of SF at the time, Čapek’s Robots are not mechanical or even electromechanical beings. Rather they are cloned synthetic organic humanoids, somewhat akin to the Replicants in the film Blade Runner, rather than an organic-electromechanical hybrid like Commander Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation, though we would refer to both types as androids today, and in Philip K Dick’s 1968 classic Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? on which Blade Runner was based, which expanded on the themes of R.U.R., not only an oppressed underclass struggling for freedom, but also trying to grasp the very nature of their existence.

The term ‘robot’ was coined in 1920 in the play R.U.R. – Rossum’s Universal Robots, by Czech playwright Karel Čapek. The science fiction story dealt with themes we still find in SF today, of an artificial humanoid underclass, which eventually rises up, wiping out their human masters. Unlike the majority of SF at the time, Čapek’s Robots are not mechanical or even electromechanical beings. Rather they are cloned synthetic organic humanoids, somewhat akin to the Replicants in the film Blade Runner, rather than an organic-electromechanical hybrid like Commander Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation, though we would refer to both types as androids today, and in Philip K Dick’s 1968 classic Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? on which Blade Runner was based, which expanded on the themes of R.U.R., not only an oppressed underclass struggling for freedom, but also trying to grasp the very nature of their existence.

The notion of a Robot or artificial servant has long been a part of folklore and fantasy. In the earliest Judaic traditions recorded in the Talmud, even Adam was originally created from dust, “kneaded into a shapeless husk” forming a Golem. The powerful man-like creature, formed from magic and mud, and enlivened by the words of God has made for lively stories ever since. In many of the stories, the creature often proves a double-edged sword, the most famous story being that of The Golem Of Prague, from the late 16th century. The creature was supposedly created by the Rabbi of Prague, Judah Loew Ben Bezalel, from the mud of the Vltava river, and brought to life through rituals and Hebrew incantations and the use of a shem, one of the names of God inscribed on a piece of paper and placed in the Golem’s mouth. It’s purpose to defend the Jewish quarter from attacks. In one version of the story, the Rabbi forgets to remove the shem on the Sabbath as required, and the Golem falls to dust, a simple lesson about respecting the Sabbath. In others the Golem falls in love and is rejected, and becomes a violent monster, and goes on a murderous rampage. A more complex lesson, and one we see echoes of in Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, first published in 1818.

The term automaton, a self-operating machine, was first used by Homer around 700BC to describe a device that opened doors automatically, and mechanically propelled wheeled tripods. In Greek mythology there are numerous occurrences of automata. The God of smiths, artisans, craftsman and metallurgists, Hephaestus created automata in his workshop, and Prometheus not only stole fire from Hephaestus, but also knowledge of the mechanical arts. In some versions of the myth of Prometheus, the eagle that tormented him for his crime of giving fire and knowledge to mankind was a mechanical creature created by Hephaestus.

Many complex mechanical devices existed in the Hellenistic world, however few survive. The Antikythera mechanism, an ancient analog computer designed to calculate astronomical positions, is one of the most remarkable. Most automata were simple devices, mechanical toys, religious idols, or equipment for demonstrating the wonders of scientific principles. When the works of the Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria were translated into Latin in Western countries in the 16th century from Arabic editions, it lead to the re-creation of machines including automatic siphons, a fire engine, the aeolipile – a steam powered jet turbine, a water organ and a programmable cart.

Knowledge of Greek mathematics and mechanics had never been lost in the Arab world. In the 8th century there were wind-powered statues above the domed gates of Bagdad that turned automatically. In the 9th century, the Banū Mūsā brothers invented an automatic flute player, described in the Book of Ingenious Devices. In 1206 Al-Jazari described complex programmable humanoid automata and other machines in the Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. Al-Jazari’s Hand-Washing Automaton, was the first known humanoid mechanical device with a practical purpose. It featured a female serving figure that stood by a wash basin. After washing, one would pull a lever; the basin would drain, and the automaton would turn and bend and pour, refilling the basin automatically. Essentially the first true robot.

At the end of the 13th century, Robert II, Count of Artois built a pleasure garden at his castle at Hesdin, in northern France, with automata including monkey marionettes, mechanical birds, mechanized fountains and a bellows-operated organ. Automata were mechanical wonders, the playthings of Lords and Kings. The Count’s walled park was famed for its automata well into the 15th century before it was destroyed by English soldiers in the 16th century.

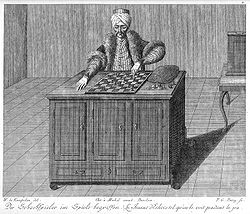

In 1770 Wolfgang Von Kempelen constructed The Mechanical Turk, The Automaton Chess Player, to impress the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. The Turk toured Europe and the Americas, defeating most challengers, including the Emperor Napoleon and Benjamin Franklin. However, it was revealed to be a fake in 1820. While it was an elaborate machine, The Turk employed a chess master hidden within its cabinet to operate the levers and pulleys that made the Turbaned mechanical master appear to play.

In 1770 Wolfgang Von Kempelen constructed The Mechanical Turk, The Automaton Chess Player, to impress the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. The Turk toured Europe and the Americas, defeating most challengers, including the Emperor Napoleon and Benjamin Franklin. However, it was revealed to be a fake in 1820. While it was an elaborate machine, The Turk employed a chess master hidden within its cabinet to operate the levers and pulleys that made the Turbaned mechanical master appear to play.

The 3rd century Chinese Lie Zi text describes an encounter from a thousand years earlier between King Mu of Zhou and an artificer called Yen Shih, who proudly presented the King with a life sized, human shaped mechanical figure.

It walked with rapid strides, moving its head up and down, so that anyone would have taken it for a live human being. The artificer touched its chin, and it began singing, perfectly in tune. He touched its hand, and it began posturing, keeping perfect time…As the performance was drawing to an end, the robot winked its eye and made advances to the ladies in attendance, whereupon the king became incensed and would have had Yen Shih executed on the spot had not the latter, in mortal fear, instantly taken the robot to pieces to let him see what it really was. And, indeed, it turned out to be only a construction of leather, wood, glue and lacquer, variously coloured white, black, red and blue.

The Han Fei Zi and other Chinese texts describe the philosopher Mozi and his contemporary the inventor Lu Ban creating mechanical flying birds in the 5th century. Reportedly when the founder of the Ming Dynasty Hongwu in the 12th century was destroying the former palaces of the Yuan Dynasty, many mechanical devices were found, including automatons in the shape of tigers. Yen Shih’s creation, like the Golem, is undoubtedly fabulous, a story, or like The Turk, an illusion. However a fascination with mechanical creatures has also been part of Chinese culture since ancient times.

Despite the Western perception that a Samurai in helmet and full laquer armour appears to be a robot (see Terry Gilliam’s wonderful 1985 film Brazil, for example), Japan seems to have not come to the creation of automatons until the introduction of Western clockwork technology in the 17th century. What they immediately brought to automatons was artistry, exquisiteness, and a distinct notion of service.

Karakuri ningyō are mechanized puppets or automata. Karakuri means mechanism or trick, and the two characters that form ningyō mean person and shape; translated as puppet, doll or effigy. While there were larger Karakuri used in theatre and in religious festivals, used to perform traditional myths and legends, the Zashiki karakuri, the tea serving doll, brought the robot to the everyday home. While humans it seems have always had a fascination with the notion of artificial humans, the Western conception of the robot was the Golem, the slave, the homunculus, the monster, perceived as a threat. The Japanese conception from the first has been one of service and delight.

Karakuri ningyō are mechanized puppets or automata. Karakuri means mechanism or trick, and the two characters that form ningyō mean person and shape; translated as puppet, doll or effigy. While there were larger Karakuri used in theatre and in religious festivals, used to perform traditional myths and legends, the Zashiki karakuri, the tea serving doll, brought the robot to the everyday home. While humans it seems have always had a fascination with the notion of artificial humans, the Western conception of the robot was the Golem, the slave, the homunculus, the monster, perceived as a threat. The Japanese conception from the first has been one of service and delight.

The Edo period tea serving robot was designed to give pleasure to guests in one’s home. Small, with serene features, exquisitely dressed, powered by a spring and operated by wooden levers and cams, the delightful little creature would move forward a set distance, bearing a cup of tea, its feet moving as if walking. It would then bow its head, inviting the guest to take the tea. It would stop and wait, and when the empty cup was replaced in its arms, it would turn and return to where it started.

The same conception seems to have continued into the 21st century, with Kirobo, the first talking humanoid robot that has travelled into space, assisting with experiments on the International Space Station. In Kirobo we can perhaps see a little of Astro Boy, the robot boy created by Osamu Tezuka in 1951, created in the image, and perhaps with the soul, of his inventor’s dead son, a Robot Boy with a human heart, fighting against prejudice and fear in both robots and humans. We can also see Kirobo’s ancestry in the Zashiki karakuri.

The same conception seems to have continued into the 21st century, with Kirobo, the first talking humanoid robot that has travelled into space, assisting with experiments on the International Space Station. In Kirobo we can perhaps see a little of Astro Boy, the robot boy created by Osamu Tezuka in 1951, created in the image, and perhaps with the soul, of his inventor’s dead son, a Robot Boy with a human heart, fighting against prejudice and fear in both robots and humans. We can also see Kirobo’s ancestry in the Zashiki karakuri.

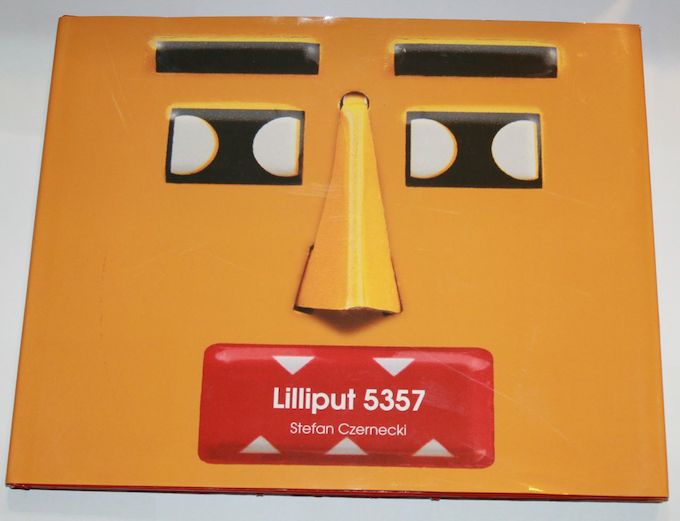

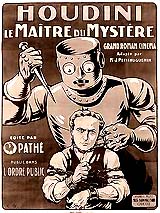

Robot Lilliput 5357, the first tin toy robot, although Japanese, owes its heritage to the conception  of the robot as alien monster in Western pulp Sci-Fi. Lilliput was the first mass produced Robot tin toy, created by the Kuramochi Shoten Company in Japan around 1939. By that time the modern notion of a Robot, an artificial being created through technology, rather than magic, was emblazoned in the human psyche. In 1921 Harry Houdini starred in the French produced serial The Master Of Mystery, as Secret Service Agent Quentin Locke, who battled against a criminal cartel served by the evil Automaton Q. Fritz Lang’s Maschinenmensch, the robot Femme Fatale deceived an underclass of rebellious workers to their doom in Metropolis in 1927. James Whale’s film of Frankenstein had been scaring audiences since 1931. Countless pulp fiction covers featured evil rectilinear robots, monstering distressed damsels barely able not to fall out of their clothing.

of the robot as alien monster in Western pulp Sci-Fi. Lilliput was the first mass produced Robot tin toy, created by the Kuramochi Shoten Company in Japan around 1939. By that time the modern notion of a Robot, an artificial being created through technology, rather than magic, was emblazoned in the human psyche. In 1921 Harry Houdini starred in the French produced serial The Master Of Mystery, as Secret Service Agent Quentin Locke, who battled against a criminal cartel served by the evil Automaton Q. Fritz Lang’s Maschinenmensch, the robot Femme Fatale deceived an underclass of rebellious workers to their doom in Metropolis in 1927. James Whale’s film of Frankenstein had been scaring audiences since 1931. Countless pulp fiction covers featured evil rectilinear robots, monstering distressed damsels barely able not to fall out of their clothing.

Despite the cute name, and the diminutive size (clearly, if a robot is named Lilliput, after the country of tiny people in Jonathan Swift’s 1726 fantasy Gulliver’s Travels, it is not a miniature of a giant robot, but rather a full sized miniature robot), Lilliput 5357 features sharp teeth in a red maw, sinister mechanical eyes, silver claws, and the lithograph on the box shows him jetting a deadly stream of smoke from his mouth and swinging his arms in a chaotic manner. This is a destructive robot, and doubtless many children would have had hours joyful play sending Lilliput 5357 crashing through block cities and wreaking havoc on toy trains. Except WWII intervened, and consequently the original Robot Lilliput 5357 is very scarce, much sought after by tin toy and robot collectors, and fetching upwards of $1000 at auction.

Despite the cute name, and the diminutive size (clearly, if a robot is named Lilliput, after the country of tiny people in Jonathan Swift’s 1726 fantasy Gulliver’s Travels, it is not a miniature of a giant robot, but rather a full sized miniature robot), Lilliput 5357 features sharp teeth in a red maw, sinister mechanical eyes, silver claws, and the lithograph on the box shows him jetting a deadly stream of smoke from his mouth and swinging his arms in a chaotic manner. This is a destructive robot, and doubtless many children would have had hours joyful play sending Lilliput 5357 crashing through block cities and wreaking havoc on toy trains. Except WWII intervened, and consequently the original Robot Lilliput 5357 is very scarce, much sought after by tin toy and robot collectors, and fetching upwards of $1000 at auction.

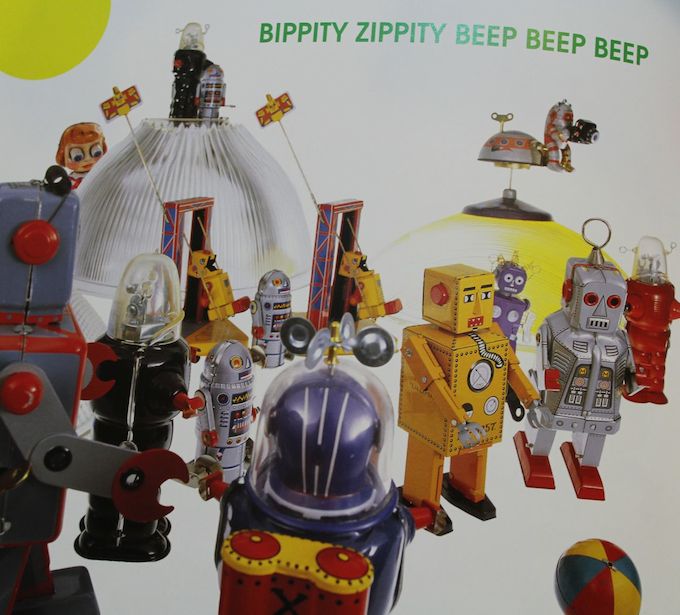

Fortunately, until an original becomes available, there are numerous inexpensive reproductions available. There’s even a book by popular children’s author Stefan Czernecki, which goes some way to renovating Lilliput 5357’s reputation. Using his own collection of tin toys and robots, the book Lilliput 5357, published by Simply Read Books in 2006 (which also seems quite scarce), presents a simple adventure, with bright colours and lots of simple word sounds, telling the tale of the little robot trying to find a new place to play after being bullied by mean robots. Designed by Katsuni Hirotani, with text in English and Japanese, it presents Lilliput 3537 as a child, rather than monster. A robot should delight, a robot should play. Whether as technologically complex as Kirobo, or as simple as a wind-up toy like Lilliput, robots are the children of our hands and imaginations, Prometheus’s gift. They are only monsters if we make them that way.