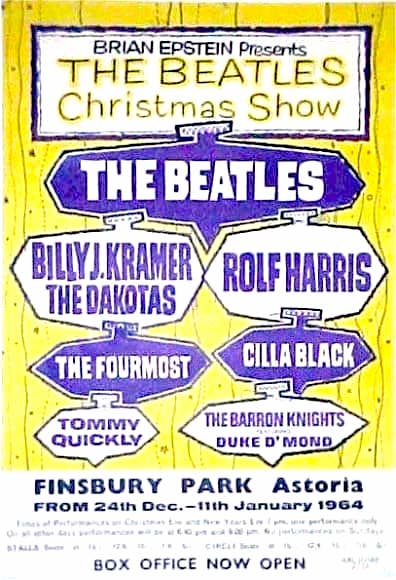

Following the runaway success of the albums Please Please Me and With The Beatles in 1963 and a string of number one singles including From Me To You, She Loves You and I Want To Hold Your Hand, the Fab Four’s manager Brian Epstein organized The Beatles Christmas Show at the Finsbury Park Astoria Theatre in London, a kind of musical and comedy variety night with acts including Rolf Harris, Cilla Black, The Barron Knights, Tommy Quickly, The Fourmost and Billy J Kramer and The Dakotas, with John, Paul, George and Ringo doing comedy skits between the support acts, and then ending the night with a set including Roll Over Beethoven, She Loves You, This Boy, I Wanna Be Your Man, Till There Was You, All My Loving, I Want To Hold Your Hand, That’s What I Want and Twist And Shout.

The show ran from the 24th December 1963 to the 11th of January 1964. They didn’t have much time to rehearse for the skits, the fans didn’t care. 100,000 tickets had sold out a month before opening night, and the audiences went wild – a phenomena that would be repeated in the upcoming UK and world tours that saw Beatlemania sweep the US, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, The Netherlands and other countries throughout 1964.

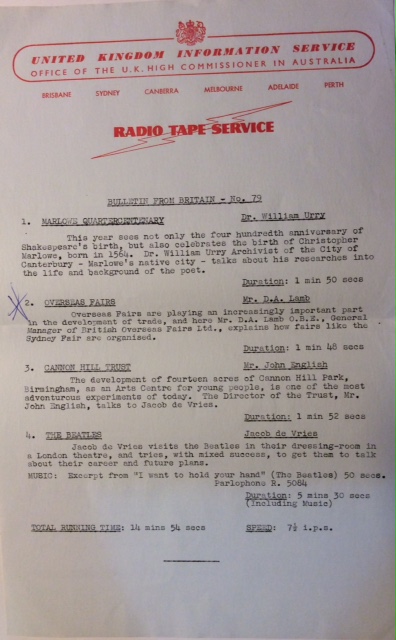

Before any of that happened, early in January 1964, The Beatles were visited in their Finsbury Astoria dressing room for an interview for a staid little radio magazine show presented by Jacob De Vries that brought the quaint, idyllic and eccentric stories of England to one the far flung reaches of the Empire, by the United Kingdom Information Service on behalf of the Office Of The UK High Commissioner in Australia.

The show begins with a jaunty tune – a rendition of Big Ben’s Westminster chimes. Then – “Bulletin For Britain – a programme of people, places and events introduced by Jacob De Vries.” It tends to present stories on the Care and Cleaning Of London Statues, for example. Or British Seed Exports for 1963 discussed in an interview with Mr W W Johnson, President of The United Kingdom Seed Trade Association. Or the Jig-Saw Puzzle Club – a puzzle library run by Mrs Margaret Waterfield. I am not making this stuff up! Sometimes something more exciting presents, such as an interview with Prima Ballerina Dame Margot Fonteyn, or Donald Campbell, on his upcoming 1964 world speed record attempt. These are field interviews – with his portable recorder, De Vries visits the Royal Gardener at the Palace, or (to paraphrase) Lord Such-and-Such in his 1904 Napier at a London car rally. You can hear the royal song birds in the manicured trees or the thrum of stately engines in the park. As curios they have a certain fascination of their own.

But even Jacob De Vries half jokingly fears for his reputation, interviewing four young rock n rollers, getting ready for a performance.

The recording begins with an 18 second bite from the current single, I Want To Hold Your Hand – then Jacob De Vries voice – although a South African he has a distinctly BBC RP voice. He sounds like a toff, with no hint of an accent. Unlike the Liverpudlians that follow.

Jacob – No need to tell you who that was, The Beatles of course, four young men from Liverpool who have broken all records in the world of pop music, six and a quarter million pounds worth of records of The Beatles were sold last year, their fifth single disc, I Want To Hold Your Hand which you heard just now, sold three-quarters of a million even before it reached the shops. They took Paris by storm, New York went mad about them.

It was shortly before their American tour that I met them in their dressing room of the Finsbury Park Astoria here in London. John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, a few minutes before they went on the stage. And as you’ll hear anything goes in a Beatles interview, my reputation probably too.

I started by asking the ringleader, John Lennon, how they all began.

John – Well (laughter) I don’t know, it just started about three years ago, in Liverpool, and we Beatled about, and then we went to Hamburg, and Beatled, and we came back to Liverpool and Beatled, and then we went to Hamburg and Beatled, then we came back to Liverpool and Beatled, and then we made a record.

Jacob – Why Beatle?

John – Why not? A rose by any other name would smell as Beatle.

Jacob – Hmmm (laughter)

Jacob – Let’s turn to Paul McCartney. Did you at that time…

Paul – Yes Bob?

Jacob – Yes, who did you say, Pop?

Paul – No, Bob.

Jacob – Bob?

Paul – Yes.

Jacob – I’m not Bob. (laughter)

Paul – Well there you go, don’t you? (laughter)

Jacob – Go on. Ya-kob.

Paul – Ya-kob. There Yakob.

Jacob – Good. Uh Paul, when you were still at school and you started this skiffle group, did you have any idea that you were going to sit here in the Astoria, that you were going on Royal Command performances, on trips to the States?

Paul – No I didn’t have any idea at all, Bob. About that. No idea at all, because you know, you just don’t think of that sort of thing do you Bob?

Jacob – No you don’t, Bob, but did you have any dreams, Bob? (laughter)

Paul – Now don’t start calling me Bob! (laughter) Well you know you obviously dream about that sort of thing, but you never think it will really happen to you.

Jacob – What would you be doing now if you hadn’t been a Beatle?

Paul – I think really what I might have been doing was teaching, but I was saved in the nick of time. But this is the life for me, hey, Bob? (laughter) OK Bob?

Jacob – Thanks very much, Bob.

Paul – OK All the best.

Jacob – Let’s turn to the other Bob, George Harrison. George, aren’t you sometimes frightened by all this adulation, the hysteria that you create amongst the teenaged fans?

George – Nah, not at all, Dave. I mean, I’d be frightened if they all stopped shouting and screaming, coming to see the shows. Sometimes you do get a bit worried if something goes wrong and somebody’s got hold of you by the hair but it doesn’t really matter.

Jacob – It’s not Dave by the way, it’s Charles.

Paul – Don’t let things like that get you down, will you…

Jacob – I don’t mind at all…

Paul – I’ve known some people go through life with names like Rudolph and things but they just don’t seem to worry about it.

Jacob – Well Rudolph is almost as good as Ringo, isn’t it? Ringo you were the last to join them?

Ringo – Yeah, because they’re a bit older than I am. (laughter) I’d only just started school when they started. It’s not a lie.

Jacob – Have they been to school? I didn’t…

Ringo – Oh, yes, yes, Paul was there Tuesday, May, 1964.

Jacob – But John, coming back to you, this question of the hysteria. When they storm you after a show, and you know, tear the clothes off your back, aren’t you really afraid?

John – Well I’ve never had ’em, I’ve only lost a button I think in eight months.

Jacob – Not a vital one I hope.

John – Oh no that one has zips.

Jacob – Now, how much longer do you think this Beatling is going to last?

John – Well about five hours I think.

Jacob – Ah, no no, that’s tonight.

John – Oh yes, well, I don’t know, if I knew I’d take out an insurance about it.

Jacob – Well what are you going to do afterwards?

John – I’m going to retire.

Jacob – You’ve made enough money, have you?

John – Well if we kept it on for four or five years we will have.

Jacob – What are you going to do with all that money?

John – I don’t know, I think, you know, I might go into recording myself. As long as you’ve got the money it doesn’t matter.

Jacob – Paul, what about you?

Paul – What was the question you asked me, I didn’t…could you please rephrase that?

Jacob – Yes, I said if everything dries up now, the golden and silver discs and things like that, what would you do?

George or Ringo? – (background) Melt them down.

Paul – It’s an interesting question that, I think as far as I’m concerned, I might just carry on with the song writing bit, you see, because John and I have been writing these songs for about two years now, and I think that even if our popularity waned, (waned – it’s the way I say it) we might still carry on writing these songs, whiting these songs I should say.

Jacob – You and John are of course the two writers of the group, Ringo…

Ringo – Yes?

Jacob – The drummer is always in demand, so I don’t think you’ll have any problems for the after The Beatles life.

Ringo – Drummers? I play washboards.

Jacob – Ah, that’s what it is. I’m sorry I thought it was a drum. You could have fooled…

Ringo – …well that’s it you see.

Jacob – (To George) What about you? What are you going to do, in the life after The Beatles?

George – Sail on a yacht around everywhere, and have a good time. Olé.

Jacob – A good time? Aren’t you having that now?

George – Yeah, but I mean, I mean if we’re not doing this the other good time I’d be having would probably be just traveling around in the sun and eating.

Jacob – John, the last question about plans this year, you’re going touring, which countries are you going to visit, what are your plans?

John – We come back from the States and make a film in Britain and then we go to Holland in May, and somebody’s been muttering about Australia and Germany and Israel, but I can’t see how we’re going to do all those places in a year, but, we’ll be doing a bit of travelling.

Jacob – You’re going to be kept pretty busy. Do you ever have spare time, to relax?

John – Yes, now.

Jacob – What do you do when you relax, do interviews? (laughter)

John – We get enough, you know, we’re not overworked.

Jacob – Well thank you very much indeed, chaps, and have a good show, a good success, goodbye.

The Beatles – Goodbye, cheerio! Bye Charles, Eric, See you Bob!

The last few bars of I Want To Hold Your Hand fades back in, and de Vries, back in the studios of the United Kingdom Information Service, gives the last word to Theodore Strong in in a quote from the New York Times, from the 10th of February, 1964, who said, musicologically The Beatles have a tendency to build phrases around the unresolved leading tone. This precipitates the ear into a false modal frame that temporarily turns the fifth of the scale into the tonic, momentarily suggesting the Mixylydian mode. But everything always ends as plain diatonic all the same.

Jacob concludes – Well I don’t know, this confuses me even more, and I’m not at all sure now who I am, Dave, Eric, Rudolph, Tom or what have you, I only hope the announcer remembers. Goodbye.

Again with some generic radio news in conclusion type music playing the announcer declares, “Bulletin From Britain was introduced by Jacob de Vries.”

Jacob De Vries went on to become a well known figure in BBC sports reporting, and we all know the world changing genius that The Beatles became. Of course this rough transcription doesn’t capture the off the cuff, humorously bantering style of the interview, with so many hints of what was to come. It really is a program made to be listened to.

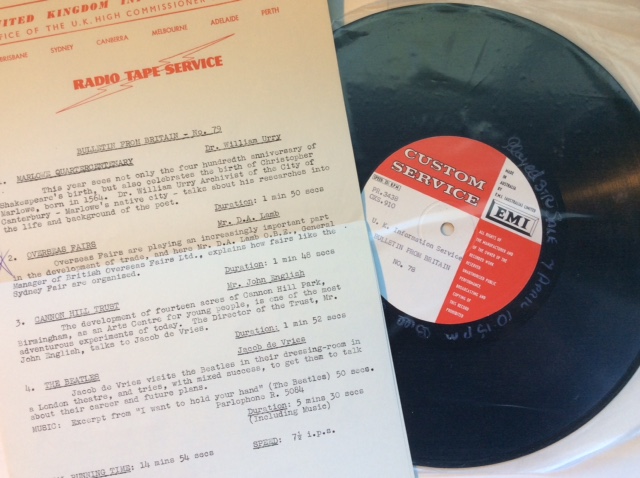

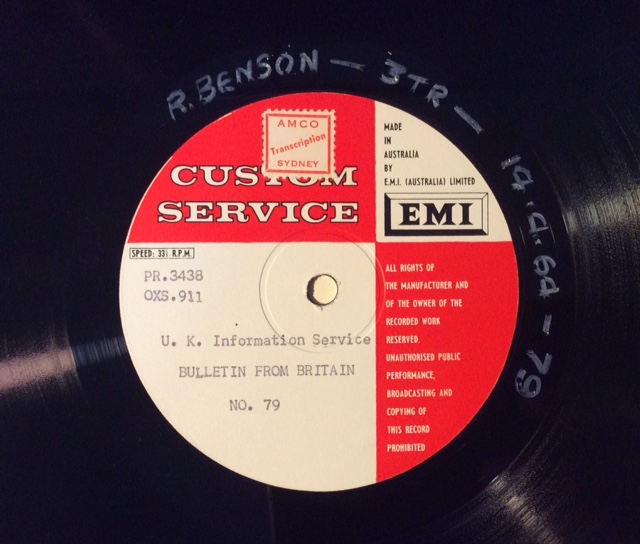

The record is a 10 inch 33 1/3, with one programme on each side. Made by EMI Custom in Australia from master tapes provided by the UK Information Service, then distributed to radio stations who carried the series. From the notation in the matrix of the record, made in some kind of white waxy crayon or marker, it was played by R. Benson from 3TR Radio, based in Sale, Gippsland, Victoria, in south eastern Australia. The record still has the foolscap information sheets on UK Information Service letterhead that list the recorded contents.

From the asterisks marked on those sheets it looks like 3TR played an interview with Mr C A Waud from the Ministry of Public Works on The Care of London Statues, and an interview with Mr D A Lamb OBE, General Manager Of British Overseas Fairs Ltd, explaining the important role of fairs in the role of trade. Just the important stuff. Not the piece on Four Hundred Years of Shakespeare or the Quartercentenary of his contemporary the poet Christopher Marlowe, not the piece on the development of Cannon Hill Park in Birmingham as a youth arts centre, not the interview with Sandy Duncan on Britain’s prospects for the 1964 Olympics, certainly not a piece on the probably scruffy mop-topped Liverpudlian rock n roll singers.

I suspect such records tended to be treated in a fairly utilitarian manner by the radio stations of the day. A few dozen would have been pressed for the various radio stations around Australia that carried the program. They were played while of current interest, perhaps discarded when the next episode arrived, perhaps archived for a while and then discarded when space required or technology changed to more compact formats. Somehow this one in its original striped brown paper sleeve, with its original information sheets folded up inside ended up at an op shop in South Gippsland.

How rare is it? This is of course an important question, to record collectors, to Beatles collectors, to Beatles historians. The Beatles are covered extensively online. There are lists of interviews, biographies, film clips, audio clips, histories, and extensive discographies. Though I can’t find a mention of this interview anywhere. Exactly what is a rare Beatles record, or an apparently lost Beatles interview, worth?

The first four numbered copies of the 1968 album The Beatles (better know as The White Album) were owned by the four Beatles. Ringo’s copy, no.1 was sold in 2016 for US$790,000 with proceeds going to The Lotus Foundation – a charity founded by Ringo and his wife Barbara Bach. Their very first demo, which featured the first song written by John Lennon, Hello Little Girl, and Til There Was You by Paul McCartney and The Beatles on the reverse, which manager Brian Epstein transferred onto vinyl from a demo tape at a HMV record store so he could more easily play it for record companies, sold in 2016 for $110,000.

Other early demo recordings of which there are only a few known copies, have exchanged hands for $20,000 or more, mint early original pressings of their albums have sold in the $1000s. So what exactly is a possibly rare recording of a lost interview segment for an obscure radio program worth? What is it worth to hear this interview, from just before Beatlemania swept the world?

The current owner says it is priceless.

Search Here For More Rare Beatles Vinyl