“I don’t think the Tolkien estate liked those films. I don’t think ‘The Silmarillion’ will go anywhere for quite a long time.”

This reasonably ambiguous statement was interpreted by all to conclude that Jackson had actually asked for the rights to make the film and was refused. You could go with that theory, or that Jackson already knew that he would be unable to obtain the rights so there was little point in pursuing the matter. Whatever the case, the frenzy surrounding the question of whether or not he will make the film continues.

To begin, let us accept a fact.

He will never get the rights

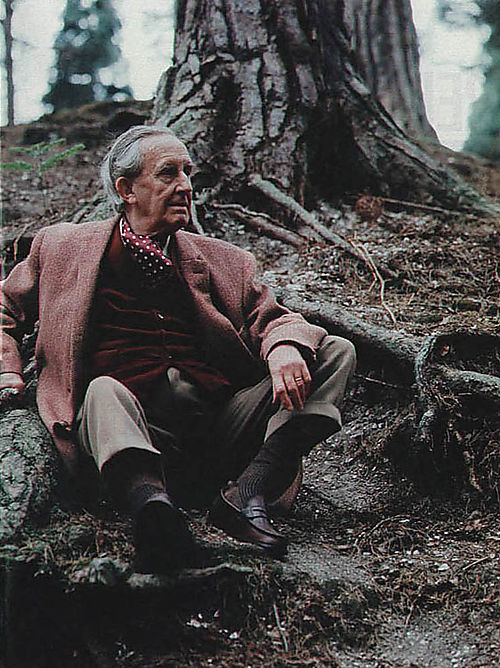

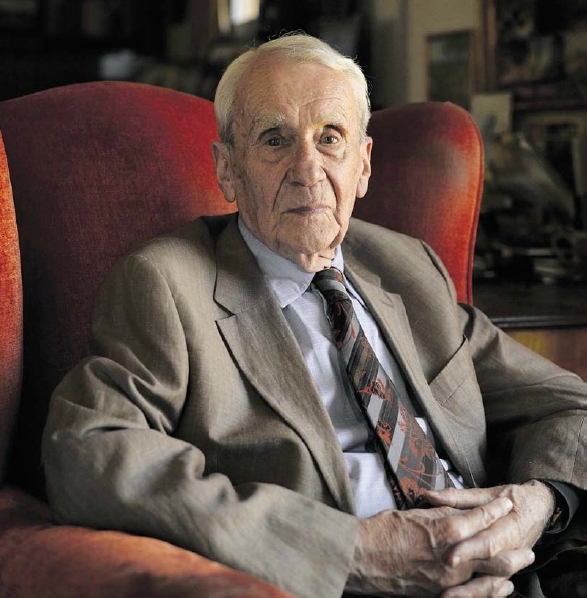

Peter Jackson will not obtain the rights to make a film adaptation of The Silmarillion in his lifetime, and nor will any other film-maker. Unlike The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, Christopher Tolkien, JRR Tolkien’s last surviving son, owns the rights to the book. In fact, Tolkien never finished The Silmarillion. It was compiled, edited and published posthumously by Christopher. To say that Tolkien considered The Silmarillion his greatest work and that Christopher has an emotional attachment to the book is understating things.

The Silmarils are in my heart…

In a letter to Stanley Unwin in 1937 Tolkien expressed his gratitude that The Silmarillion was not “rejected with scorn”. What had begun on scraps of notepaper dating back to 1917 would not see publication in his lifetime. Tolkien had submitted Quenta Silmarillion, an early form of the book to his publishers, Allen and Unwin, who had asked for a sequel to The Hobbit. It was rejected, somewhat firmly, and while Tolkien obviously could not have been happy with the outcome, he bravely turned to discussing ideas for the next book with Stanely Unwin, while still demurring “what more can hobbits do?”. 1

It took him twelve years to finish the manuscript for the ‘sequel’, The Lord of the Rings, the final stages completed in 1949. A dispute with Allen and Unwin saw the actual publication put back another five years. Tolkien intended to have The Silmarillion published along with The Lord of the Rings, and after the initial rejection by Allen and Unwin, he offered it to Collins. Although Collins had initially expressed the interest in taking on both books, the length of The Lord of the Rings changed their mind. Ironically that publisher, now Harper Collins, publishes all of Tolkien’s work today. Finally Allen and Unwin, after much dithering about the page count, published the The Fellowship of the Ring as the first instalment in 1954, and The Silmarillion was again shelved.

I grew up in the world he created…

Christopher Tolkien still has the foot-stool that he used to sit on, at age six, listening to his father’s stories. Tolkien’s children were always closely involved with their father’s work, they heard much of the work in progress that became The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and the series of stories posthumously published as Tales from the Perilous Realm. But Christopher’s involvement in his father’s work went beyond bedtime stories. “My father could not afford to pay a secretary,” he says. “I was the one who typed and drew the maps after he did the sketches.” Enlisted in the Royal Air Force, Christopher left for a South African air base in 1943, where every week he received a long letter from his father, as well as chapters from the novel that was under way. “I was a fighter pilot. When I landed, I would read a chapter.” But Christopher knew his father had not forgotten The Silmarillion. It was understood between them that Christopher would take up the task if his father died without having completed it.

I was in my father’s office at Oxford. He came in and started looking for something with great anxiety. Then I realized in horror that it was The Silmarillion, and I was terrified at the thought that he would discover what I had done – Christopher Tolkien discussing a dream

Christopher felt a heavy sense of responsibility after his father’s death, which must have been further compounded by the inheritance of 70 boxes of archives, each stuffed with thousands of unpublished pages. With the assistance of acclaimed fantasy author Guy Gavriel Kay, Christopher collated, edited and expanded the undated and unnumbered pages, producing the completed Silmarillion in 1977. He did not stop there. He resigned from New College at Oxford, where he had also become professor of Old English. With absolute dedication to preserving his father’s legacy, he spent eighteen years editing the unfinished work, producing twelve volumes of The History of Middle Earth. In 2007 he completed The Children of Hurin, which was originally conceived by his father in 1910 and had appeared in part in The Silmarillion, and this year published The Fall of Arthur, written in the earlier part of the 1930s. 2

“The canons of narrative art in any medium cannot be wholly different”

Selling the film rights to The Lord of the Rings were not, as is often assumed, a spur of the moment decision. JRR Tolkien made the above, rather hopeful, statement to Forrest J. Ackerman in a letter in 1957 . He had been approached by Ackerman, Morton Grady Zimmerman, and Al Brodax, who wanted to produce an animated version of The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien was not a rich man yet, and the problem of his children’s future inheritance tax weighed heavily on his mind. Tolkien was not entirely averse to the idea of his work being adapted into an animated film, but he was still protective of his work and rejected them on the basis of the script, saying “The Lord of the Rings cannot be garbled like that.” 3 He eventually sold the film and derived product rights to United Artists, in 1969, for £100,000. However, no films were completed in his lifetime. He died at age 81 four years later.

“He cashed the check, and he enjoyed the money before he died”

The film rights were sold to Saul Zaentz in 1976, who has since formed Middle-earth Enterprises. The animated versions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings were released in 1977 and 1978. There was no interest in the film rights until Peter Jackson decided to try and obtain them in 1995. By the end of 2001 the first instalment of Peter Jackson’s ground-breaking Lord of the Rings trilogy was about to hit the screen. The Tolkien family had kept quiet, and had not offered an opinion to the dismay of many fans, until the week before the film was released. Christopher Tolkien issued a statement through his lawyers.

‘‘My own position is that ‘The Lord Of The Rings’ is peculiarly unsuitable to transformation into visual dramatic form. On the other hand, I recognize that this is a debatable and complex question of art, and the suggestions that have been made that I ‘disapprove’ of the films, whatever their cinematic quality, even to the extent of thinking ill of those with whom I may differ, are wholly without foundation.”

Peter Jackson gave an interview the week before the film’s debut to EW, and was undoubtedly feeling a bit harassed. The British press were accusing his film of having caused a rift between Christopher Tolkien and his son Simon, and Jackson was anxious to set things straight. However when questioned about the statement Christopher had released he said

”They can have opinions about the movie, but to have an attitude about the fact that the film got made in the first place is a little bit unfair to the people that own the rights because the rights were sold by J.R.R. Tolkien himself in 1968. He cashed the check, and he enjoyed the money before he died. The people who bought the rights off Tolkien should be allowed to make the film that they paid for.”

That statement, while factual, was not without a touch of bile, and for someone who professes to be such an impassioned Tolkien fan, it was disappointing.

As for the supposed wealth Tolkien enjoyed from selling the film rights, that went to said taxes. He did however spend some of the fortune he was accumulating from the sales of books in his retirement, while his wife Edith was treated to a new wardrobe, Tolkien developed a penchant for brightly-coloured velvet waistcoats. Most of the money was spent on his beloved family.

A history of dispute

A history of dispute

Those who did write on such (copyright) matters were often rewarded in unexpected ways; breeder of jersey cattle asking if he could use the name ‘Rivendell’ as a herd-name received a letter from Tolkien to the effect that the Elvish name for Bull was mundo, and suggesting a number of names for individual bulls that might be derived from it.4

It was, in fact, New Line and Middle-earth Enterprises that started all the bad feeling. Firstly New Line failed to pay out royalties. Harper Collins and the Tolkien Estate sued them for $150 million, as well as observers’ rights on the next adaptations of Tolkien’s work. The original contract stated that the Tolkien Estate must receive a percentage of the profits if the films were profitable. Cathleen Blackburn, lawyer for the Tolkien Estate in Oxford, said, “These hugely popular films apparently did not make any profit! We were receiving statements saying that the producers did not owe the Tolkien Estate a dime.”

It took until 2009, and a change of studios, to settle the lawsuit, which had halted production of The Hobbit. It’s worth noting that Peter Jackson also had to sue New Line over unpaid royalties.

After the lawsuit was settled, Warner Bros. President and COO, Alan Horn said “We deeply value the contributions of the Tolkien novels to the success of our films and are pleased to have put this litigation behind us.”

They “deeply valued” the Estate enough to go ahead and continue flouting the original contract, which only allowed tangible products to be sold. Warner Bros. instead started selling downloadable video games based on Tolkien’s stories, and in a disgusting move which outraged fans, attempted to enter into a contract with a casino to license Hobbit-themed slot machines. They had been successful in licensing Lord of the Rings-themed slot machines and this time Harper and Tolkien Estate were determined to stop them, slapping them with a £50 million lawsuit. Warner Bros. then counter-sued, claiming that the lack of branded slot machines in casinos and arcades, along with online games, damaged the profitability of the first film in Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. They stated the lawsuit “has harmed Warner both in the form of lost license revenue and also in decreased exposure for the Hobbit films.”

Meanwhile the money-grubbing leech Saul Zaentz bullied a small pub in Southampton last year, called of course, The Hobbit, which had been established as a homage to Tolkien’s work for more than 20 years, demanding they re-brand entirely or face legal action. It was not only fans who had had enough at this point. After Zaentz caved in to public pressure and agreed to sell them a license, The Hobbit stars Ian Mackellan and Stephen Fry paid for the license out of their own pocket. Fry said “Sometimes I’m ashamed of the business I’m in. What pointless, self-defeating bullying.”

Tolkien has become a monster…

“…devoured by his own popularity and absorbed into the absurdity of our time,” said Christopher Tolkien. “The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work, and what it has become, has overwhelmed me. The commercialization has reduced the aesthetic and philosophical impact of the creation to nothing. There is only one solution for me: to turn my head away.”

It took a long time for Christopher Tolkien to break his silence, the interview with LeMonde was his first in forty years. It is clear that the appalling treatment both the family and Tolkien’s publisher’s have been subjected to over the last decade by the film studios had finally taken it’s toll. Having carefully never offered an opinion of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings film trilogy, Christopher finally said

“They eviscerated the book by making it an action movie for young people aged 15 to 25. And it seems that The Hobbit will be the same kind of film.”

I am sorry the names split his eyes…

I am sorry the names split his eyes…

I do not think it would have the appeal of the L. R. – no hobbits! Full of mythology, and elvishness, and all that ‘heigh style’ (as Chaucer might say), which has been so little to the taste of many reviewers – JRR Tolkien 5

The “eye-splitting” Celtic names, along with the deep philosophical and theological themes that pervade The Silmarillion are among just some of the factors that make it a difficult read. Even some of the most devoted Tolkien fans struggle with it; it is a little disjointed, episodic and lacks a central character and the narrative that would follow. It’s not coincidental it is often likened to the Old Testament, it is essentially a creation tale, with the perspective Christopher Tolkien described as “the novelist inventing the story, and so retains omniscience: he can explain, or show, what is ‘really’ happening and contrast it with the limited perception of his character.” 6

The book was not well-received when it was published, as Allen and Unwin had feared forty years earlier, and as Tolkien had feared himself. The common complaints being the difficult names, the archaic text and the lack of central characters for the reader to identify with.

The heart of the matter

I am doubtful myself about the undertaking [to write The Silmarillion]. Part of the attraction of The L. R. is, I think, due to the glimpses of a large history in the background: an attraction like that of viewing far off an unvisited island, or seeing the towers of a distant city gleaming in a sunlit mist. To go there is to destroy the magic, unless new unattainable vistas are again revealed JRR Tolkien 7

It is at this point we have to consider why anyone would think the translation of The Silmarillion into film, in the authirs opinion, would be anything less than disastrous. It is not, in essence, filmable. The very depth, scope and gravity of the book does not lend itself to an action-adventure film. Doubtless there are those who have read it and think it would make a wonderful film. I suspect they are overestimating Peter Jackson’s abilities. A great film-maker he may be. The task of adapting Middle-Earth to film is no mean feat and on the whole they did an excellent job, but several of the additions they made to the story of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, have ranged from unnecessary to embarrassing. Jackson’s ardent desire to create his Warrior-Elf-Princess may have been finally realised in The Hobbit, but the vicious backlash of fans at his attempt to treat Arwen in the same manner in The Lord of the Rings trilogy forced him to withdraw her scenes at Helm’s Deep from the film.

Herein lies the problem. A film-maker must cater to the audience. And where Jackson was compelled to do so he lost the heart of the book along the way. The film, in fact, only represents the surface of The Lord of the Rings, it cannot claim the philosophical depth of the text. If JRR Tolkien really only considered The Lord of the Rings as a sequel to his “real” work, The Silmarillion, what chance does a film-maker have of creating its equal in film?

Perhaps Professor Tom Shippey summed it up best. In his largely complimentary essay on the Peter Jackson films that was added to the third edition of The Road to Middle-Earth, Shippey observes that Jackson “is quicker than Tolkien was to identify evil without qualification, and as a purely outside force…there is the kernel here of a serious challenge to Tolkien’s view of the world, with its insistence on the fallen nature even of the best, and its conviction that while victories are always worthwhile, they are also always temporary. And this could, at last, be a problem not created by any failure to perceive ‘the core of the original’ but a grave and genuine difference between the two different media and their ‘respective cannons of narrative art’.”8

A clarification on copyright: Christopher Tolkien holds the authorial copyright on The Silmarillion, not J.R.R. Tolkien. Harper Collins has confirmed with us that, under current copyright laws, the copyright will therefore not expire until 70 years after Christopher’s death, and not in 2043 when the copyright on the works of J.R.R. Tolkien will expire. (Updated 25/01/14)

- Carpenter, Humphrey The Letters of JRR Tolkien Harper Collins 2006, pg 26 ↩

- Christopher Tolkien Interview at LeMonde/Worldcrunch ↩

- Carpenter, Humphrey The Letters of JRR Tolkien Harper Collins 2006, pg 270 ↩

- Carpenter, Humphrey JRR Tolkien A Biography Unwin 1978, pg 242 ↩

- Carpenter, Humphrey The Letters of JRR Tolkien Harper Collins 2006, pg 238 ↩

- Tolkien, Christopher The Book of Lost Tales Part One, Harper 2002, pg 2 ↩

- Carpenter, Humphrey The Letters of JRR Tolkien Harper Collins 2006, pg 333 ↩

- Shippey, Tom The Road to Middle-Earth Harper Collins 2005, pg 422-3 ↩