“buryed…without any pompe or solemn funerall…in thabbay of monks Franciscanes at Leycester” Polydore Vergil

Today marks a full year since one of the greatest discoveries in archaeological history was announced; the lost remains of King Richard III had been discovered more than 500 years after they had been laid to rest in the Greyfriars Church in Leicester. Popular culture would have us believe that after Richard III was killed in battle at Bosworth Field, his naked body was publicly humiliated, trussed and tossed into a too-small pit for a grave, left forgotten only to be dug up during the Dissolution of the Monasteries and his remains thrown into the River Soar. He may not have had a state funeral, but King Richard III was laid to rest in sanctified ground, and he also had a tomb.

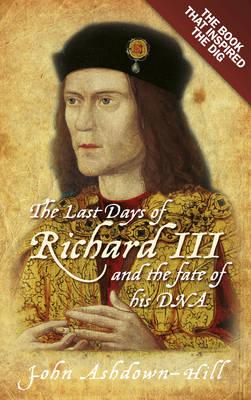

The man responsible for discovering the mtDNA sequence of King Richard III, genealogical researcher, historian and a founding member of the Looking for Richard team Dr John Ashdown-Hill joins us today to discuss the burials of King Richard III.

Can you tell us about what Richard’s first interment ceremony may have been like?

The norm for the funeral of someone important would have been for the body to be received at the church at least one day before the interment, and for Vespers and Lauds of the Dead to be celebrated, followed by at least one funeral (Requiem) mass the following day, at the end of which the burial would have taken place. But in Richard’s case it seems likely that the body was only handed over to the friars early on the morning of 25 August 1485, after it had been on display for two days. That was the morning when Henry VII left Leicester, and presumably he would have wanted to know that the body had been handed over for burial before he left.

Incidentally, in itself there was absolutely nothing unusual or improper about putting the bare body on display before burial. Henry VII had a particular motive for doing that, because he wanted to ensure that there were witnesses who could certify that Richard was dead. But Richard’s brother, Edward IV, was also laid out naked (his corpse covered with a cloth from navel to knees) for about 12 hours before his preparation for burial, so that people could come and see the body. Usually, of course, exposing a royal body naked to public gaze was a good way of making sure that myths about a murder didn’t start to spread. If the bare body had been on display, any wounds would presumably have been spotted.

We have no clear account of what took place when Richard was actually buried, but my own feeling is that the Franciscan Friars (who had links with Richard’s family) may well have requested permission to bury the body. Then as I said earlier, it would have been handed over to them on the morning of Henry VII’s departure. We know now that it wasn’t placed in a coffin, though it might perhaps have been in a shroud. The friars would have taken it through the streets to their priory without any ceremony. This probably happened early on the morning of 25 August when not many people were about.

When they reached the priory, probably the body was first laid out in the choir and a requiem mass was said or sung. There is no evidence to prove this, but I cannot believe that a religious community would have buried anyone in their church without the normal basic religious rites. It seems they had already prepared a grave for Richard at the western end of their choir, on the south side of the entrance. The grave was correctly orientated east/west, as Christian tradition required. The friars probably dug that grave on 24 August, and in order to do that they would have needed to take up some of their floor tiles.

Evidently they had no chance to measure the body before the grave was dug, because the hole they prepared turned out to be a bit too short for Richard’s remains. Even so, I can see no reason for suggesting (as some people have) that he was shoved into it in a violent way. I think the friars just laid the body in place with the head slightly up, as though he had a pillow beneath him. His head was at the western end, so that he was facing towards the high altar. Again, that was the norm for Christian burials. His arms were crossed over his genitals, but that too was a normal and proper way for a Christian body to be laid out. Despite what some people have hinted, I think there is no reason to suggest that his hands were tied together. Once the body was in place it was probably sprinkled with holy water and the short rite of burial – including the familiar words of ‘dust to dust’ would then have been celebrated. Finally the grave would have been refilled.

Incidentally, I don’t think the friars can possibly have re-laid the floor tiles. First they would have needed to wait for the earth to settle. When it had, I would imagine that instead of attempting the difficult task of piecing the tiles back into place they would simply have had a flat stone placed over the grave to tidy up their church floor.

Where was Richard buried in the Greyfriars church, and was it a place of honour?

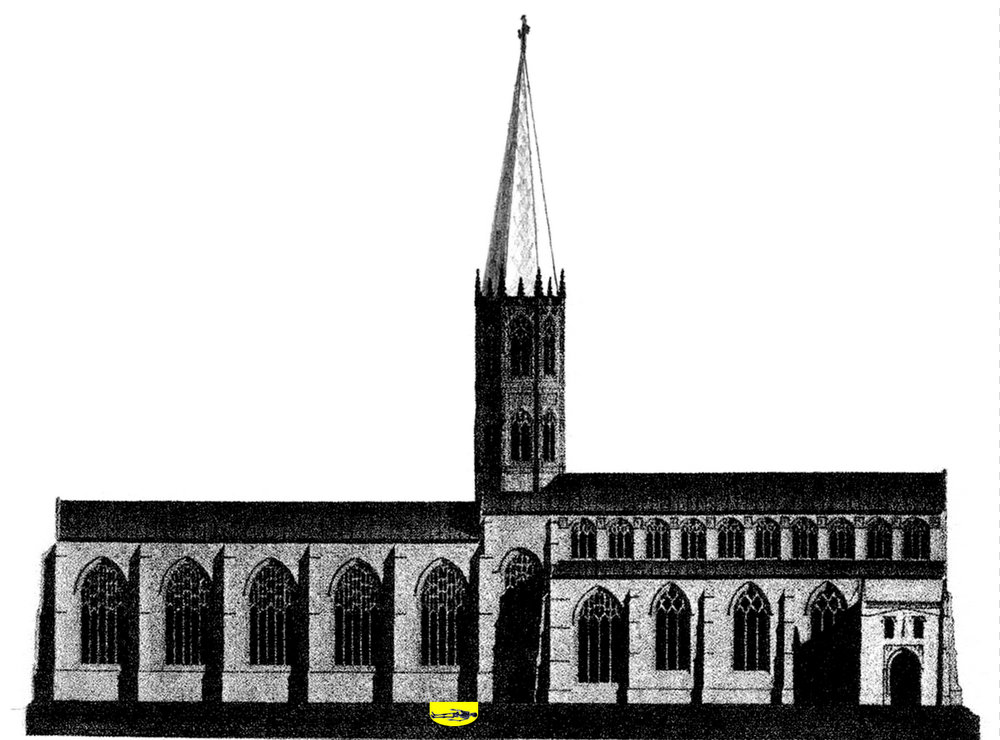

Richard was buried in the choir of the church. This was the long, east end section – the part of the church which was reserved for the friars, and the area where they celebrated all their daily hours of prayer (matins and lauds, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers, and compline). The choir was the most honourable place in a priory church for burial and was usually reserved for really significant people – but it also had another possible advantage form Henry VII’s point of view, in that it wasn’t accessible to the general public.

In fact Richard III’s burial was entirely consistent in this respect with the established pattern for burial of ousted kings of England. Edward II was buried in the choir of Gloucester Abbey, Richard II, in the choir of Kings Langley (Blackfriars) Priory, and Henry VI in the choir of Chertsey Abbey. All these reburials were later upgraded. Richard III and Edward II were not moved, but were subsequently given royal tombs where they lay. Richard II was moved to Westminster Abbey, and in 1484, Henry VI’s body was transferred by Richard III himself to St George’s Chapel at Windsor, where it was reburied roughly opposite the tomb of Edward IV.

Incidentally, the most honourable burial place in the choir would have been right in front of the high altar. But Richard was a late arrival at the Leicester Greyfriars in terms of burial, and the places near the altar had already been taken. So he was buried at the western end of the choir near the entrance arch. That way the friars had to walk back and forth past him fourteen times a day, every day, as they went in and out of the choir for their religious hours of Office.

Can you tell us about the tomb Henry VII had commissioned for Richard and the epitaph placed near his tomb?

Richard II and Henry VI both had to wait until their successor was dead before their burials were upgraded. But Richard III was luckier. He didn’t have to wait so long. Henry VII himself commissioned a tomb for Richard in 1494 – and I think the date may be significant, because it was the year the Yorkist pretender known as ‘Perkin Warbeck’ appeared to claim the throne. I think Henry VII wanted to win over Yorkist opinion, and that was one of the reasons why Richard’s tomb was commissioned at that point.

The tomb seems to have been inaugurated in August 1495, and it was made of Nottingham alabaster. That was a standard format for upper class tombs at that time – though the very finest tombs (like Henry VII’s own tomb) were made of gilded metal and hard stone. Tombs of that sort were very costly. But Richard’s tomb certainly wasn’t cheap. We don’t have the full accounts for it, but the information which has survived indicates that Richard’s tomb cost more than the tomb which his mother, Cecily, Duchess of York, commissioned for herself.

I think people can get the best idea of what the tomb might have looked like from the surviving tomb of Richard III’s brother-in-law, John de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, at Wingfield Church. That alabaster tomb was also set up in about 1495.

As for the epitaph, until my research a few years ago, most people dismissed that as a seventeenth-century invention. But I rediscovered two sixteenth-century manuscript sources for the text. The earlier of these two manuscripts was certainly written before the Dissolution of the Leicester Greyfriars – so at a time when Richard III’s tomb was still complete.

But we don’t know that the epitaph was actually inscribed on the tomb. Sometimes they were (as in the case of Henry VII), but sometimes they were inscribed on a wooden board and hung up beside the tomb. As for the text of the epitaph the surviving manuscript and early printed versions all differ slightly, some being slightly more favourable to Richard, and some slightly less favourable. Unfortunately it is hard to be certain now which form of the text is the closest to the original.

When did you come up with the idea of having a crown made for Richard’s re-interment ceremony and what is the significance of using a crown?

When the dig was due to start, in August 2012, I took with me to Leicester a modern copy of Richard III’s royal standard – because I thought if we find him, it’s usual to place a royal standard over royal remains. On 4 September 2012, when I was asked to carry the box of his bones from the Social Services car park to the van which would carry him away, Philippa Langley and I draped my royal standard over the box. But as I was carrying that box containing Richard’s remains, lots of thoughts went through my mind. And one of them was ‘Something’s missing!’ Normally, nowadays, a sovereign’s body would not only have a royal standard over it, but also a crown on top of the coffin. So that was when I decided to make sure that Richard should have a crown on his coffin when his reburial takes place.

What did you have in mind when you were designing the crown?

Well, obviously the modern kind of crown would look a bit inappropriate, so the first thing was to try to get at the kind of crown Richard would have worn. Unfortunately the fifteenth century was a time of change in terms of English royal crowns. Previously they had all been open crowns, but in the fifteenth century, closed (arched) crowns were coming into fashion, and Richard III probably wore one of those on occasions. But at his crown-wearing at Leicester, prior to the battle of Bosworth, and during the battle itself, I think he must have worn an open crown over his helmet. So I decided to go for an open crown, and took the basic design from Anne Neville’s open crown depicted in the Salisbury roll.

The next thing was the size and shape of the crown. Since Richard III’s facial reconstruction has hats to wear, details of his head size are obviously now available, so I got the measurements from Phil Stone, and ordered a crown of the right size and shape – so that, if he wanted to, Richard III could actually wear it. (But of course, he never will.)

The ornamentation of the crown was inspired by the surviving crown of Richard’s sister, Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy. That’s a very pretty, very feminine little crown. Obviously a copy of that wouldn’t really be appropriate for Richard. But we borrowed the idea of setting the jewels on top of enamelled white roses, because that’s how the jewels are set on Margaret’s crown. As for the jewels, themselves, the jeweller who is making the crown suggested sapphires and garnets, with pearls in between. I’m not certain why he proposed sapphires and garnets, but I jumped at his suggestion, because murrey and blue were the livery colours of the royal house of York.

Why do you think it is important for Richard to have a proper “state-like” funeral this time around?

Actually , the Looking for Richard project team, led by Philippa Langley, of which I was a founding member, originally thought the reburial should best be quiet and private, but followed by a grand public church service in celebration of Richard. But I think the huge interest in the event now makes that impossible. Also, if we consider how Richard himself reburied Henry VI, and how Edward IV reburied his (and Richard’s) father and brother, those were grand public occasions. So I think my view has changed on this.

What else would you like to see in the re-interment ceremony?

This is a difficult one, because what I have to say could maybe sound contentious to some people. But the thing is, I am a Roman Catholic. Therefore I know what praying for the dead means to Catholics; and how very important we think it is to pray for them. But more than just praying, we should also offer the sacrifice of the mass for the souls of the dead whenever we get the chance.

The important thing is that Richard III was also a Catholic, in full communion with Rome all his life, so I’m certain that his views on this would have been the same as mine. In fact we know for sure how important masses for the dead were to him, because he was very much on the ball about endowing such masses for his own dead relatives.

So, bearing all this in mind, I have to say that I’m not at all happy with Richard III having a reburial that is not Catholic – and by that I mean using the full Catholic ritual and having the ceremony celebrated by Catholic priests. I’m not hostile to Anglicans, but if I didn’t think their viewpoint and mine are different, then I’d be an Anglican wouldn’t I, instead of a Catholic? But I’m not. And Richard III wasn’t. So I would like him to have a full mass at his reburial. For people of my faith, you can never have too many masses for the good of your soul!

Read more in The Last Days of Richard III and the fate of his DNA: the Book that Inspired the Dig by John Ashdown-Hill, published by The History Press 2013.

Pictures © John Ashdown-Hill unless otherwise noted. Do not reproduce without permission.

Dr. John Ashdown Hill

Dr. John Ashdown Hill

I am a freelance historian; historical researcher; writer and lecturer. I am a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, and a member of the Society of Genealogists, the Richard III Society, and the Centre Europeen d’Etudes Bourguignonnes.

My doctoral research was centred upon the client network of John Howard Duke of Norfolk in North Essex and South Suffolk. Since 1997 I have regularly given historical talks, and published historical research, achieving a certain reputation in aspects of late medieval history. I was the leader of genealogical research and historical adviser on the ‘Looking for Richard‘ project, which led to the rediscovery of the remains of Richard III in August 2012. My Richard III work demonstrates, I believe, that I have a special interest in controversial topics, and a talent for taking a fresh approach, which can sometimes lead to significant new discoveries.

I have currently had five history books and numerous historical research articles published. My sixth book – The Third Plantagenet, a study of George, Duke of Clarence, is due out in March 2014. Due out in 2015 is The Dublin King, the true story of Edward, Earl of Warwick, Lambert Simnel and the Princes in the Tower. My latest book Royal Marriage Secrets recently received an excellent review in The Spectator. As a result of my work on the Richard III project I participated in British, Continental and Canadian TV documentaries on the search for Richard III. Subsequently I have also participated in a general historical documentary on the life of Richard III for the USA, and interest has been expressed in the possibility of further TV work based on two of my books.

You can visit me at johnashdownhill.com

Visit the Looking for Richard website.

Buy The Last Days of Richard III and the fate of his DNA: the Book that Inspired the Dig by John Ashdown-Hill, published by The History Press 2013

Buy The Last Days of Richard III and the fate of his DNA: the Book that Inspired the Dig by John Ashdown-Hill, published by The History Press 2013

The Last Days of Richard III contains a new and uniquely detailed exploration of Richard’s last 150 days. By deliberately avoiding the hindsight knowledge that he will lose the Battle of Bosworth Field, we discover a new Richard: no passive victim, awaiting defeat and death, but a king actively pursuing his own agenda. It also re-examines the aftermath of Bosworth: the treatment of Richard’s body; his burial; and the construction of his tomb. And there is the fascinating story of why, and how, Richard III’s family tree was traced until a relative was found, alive and well, in Canada. Now, with the discovery of Richard’s skeleton at the Greyfrairs Priory in Leicester, England, John Ashdown-Hill explains how his book inspired the dig and completes Richard III’s fascinating story, giving details of how Richard died, and how the DNA link to a living relative of the king allowed the royal body to be identified.