With the anniversary of the outbreak of WW1 approaching and a film version of Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth well into production this seems a fitting time to look at Vera’s best known literary work, and to also examine a little of her life and times and the experiences that made her the woman she was.

With the anniversary of the outbreak of WW1 approaching and a film version of Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth well into production this seems a fitting time to look at Vera’s best known literary work, and to also examine a little of her life and times and the experiences that made her the woman she was.

Vera was born in 1893 in Newcastle-under-Lyme and, as her father owned two paper mills, grew up in upper middle-class comfort, tended by a governess and servants in a household that reflected all of the middle-class values of conservatism and prejudice that prevailed at that time. In 1905 the Brittains moved to Buxton in Derbyshire, a town that Vera thought to exemplify a “mean, fault-finding spirit”. Growing up in relative isolation and under continual close supervision Vera developed a close bond with her brother Edward, a bond which would continue to influence her life long after his death.

The prejudicial views of her father, Thomas Brittain, meant that he strongly objected to Vera’s desire to attend university, despite the fact that she was obviously intellectually far superior to many of her male contemporaries who now attended Oxford. Thomas Brittain believed that the main role of education was to prepare women for marriage, a viewpoint that proves that in many respects women as recently as a hundred years ago were no better off than they had been in the middle-ages. Indeed women at this time did not even have the right to vote in Britain.

Her father eventually relented in 1914 and Vera was allowed to attend Somerville College, Oxford, one of the recently established women’s colleges at that time, having been encouraged in her quest by Roland Leighton, a friend of her brother.

Vera Brittain was undoubtedly a feminist, but it’s my opinion that this only manifested itself on a universal scale a little later in her life, her initial feminist issues were of a more personal nature and seem to be more in the way of feisty rebellion against the injustice of being told what she could or could not do based on no other circumstance than her gender.

Two months after starting college war broke out and Edward, Roland and their close friend Victor Richardson, immediately applied for commissions in the British Army. In a letter to Roland, Vera wrote; “…I am quite sure that had I been a boy I should have gone off to take part in it long ago; indeed I have wasted many moments regretting that I am a girl. Women get all the dreariness of war and none of its exhilaration”. By the end of her first year at college she decided that it was her duty to postpone her academic career in order to serve her country. Possibly accepting the propaganda of the time she believed that the war would be over in a year and that she would be able to resume her studies after this period of time. Although the Principal at Somerville, Emily Penrose, thought her talents would be of better use in the Civil Service Vera applied to join the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) as a nurse and after working at the Devonshire Hospital in Buxton, as a nursing assistant during the summer of 1915, she was eventually posted to a military hospital; the First London General Hospital at Camberwell, London during November 1915. This posting gave Vera her first glimpses of the horrific injuries that soldiers being sent back from France had received, prompting her to write to Roland that; “I have only one wish in life now and that is for the ending of the war…and wonder if, when the war does end, I shall have forgotten how to laugh”.

Vera had become engaged to Roland whilst he was home on leave during August 1915 and, possibly because of this intimacy, Roland wrote letters to Vera highlighting his disillusionment with the war, describing it as; …”a waste of youth, such a desecration of all that is born for poetry and beauty”. Having secured Christmas leave to spend time with Roland, Vera eagerly rushed to the telephone on the 26th December expecting to hear the voice of her fiancé only to be told that Roland had been shot by a sniper and had died of his wounds on the 23rd December.

Vera recalled visiting Roland’s family and finding them in “helpless distress” as they had just opened a package containing Roland’s returned kit. In her autobiography she wrote; “The garments sent back included the outfit that he had been wearing when he was hit. I wondered, and wonder still, why it was thought necessary to return such relics – the tunic torn back and front by the bullet, a khaki vest dark and stiff with blood, and a pair of blood-stained breeches slit open at the top by someone obviously in a violent hurry. Those gruesome rags made me realise, as I had never realised before, all that France really meant”. After returning to the First London General Hospital on 3rd January 1916 Vera was visited on a regular basis by Victor Richardson and also made a new friend when nursing Geoffrey Thurlow (who was also a friend of her brother) who was suffering from minor wounds and shell-shock. Vera, still grieving for Roland, found nursing badly wounded men very difficult at this time and was now fully appreciating the horrifying effects of bullets, shells, gas and bayonets on the bodies of men. Her brother Edward was wounded in the first battle of the Somme in July 1916 and was sent to Vera’s hospital at Camberwell for treatment. Thankfully for Vera he was not badly wounded and was quickly discharged to begin a prolonged period of convalescent leave and in August it was announced that he had been awarded the Military Cross.

In September 1916 Vera received news that she was to be posted to Malta and whilst there Vera maintained regular correspondence with Victor, Geoffrey and Edward. Vera received news in April 1917 that Victor had been badly wounded at Arras. Later that same month she received a letter from Geoffrey at the same time as receiving news of his death at Monchy-le-Preux. Vera decided to return home and resolved to marry Victor and care for him on his discharge from hospital, but this never transpired as Victor died of his wounds soon after Vera’s return to England. With Edward now fighting on the Western Front Vera returned to duty as a VAD, requesting a posting to France and in August 1917 Vera joined a small draft of nurses sent out to the 24th General Hospital at Etaples where she initially nursed German prisoners, the majority of whom were mortally wounded.

Vera’s wartime experiences would turn her into a committed pacifist and this viewpoint was becoming increasingly evident in the letters she sent home to her mother. On the 5th December 1917 she wrote; …”I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case – to say nothing of ten cases – of mustard gas in its early stages – could see the poor things burnt and blistered all over with great mustard coloured suppurating blisters, with blinded eyes – all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke… They certainly don’t reach England…and yet people persist in saying that God made war, when there are such inventions of the Devil about”. In Testament of Youth she added; “…all day, all night – gassed men on stretchers clawing the air – dying men reeking with mud and foul green stained bandages, shrieking and writhing in a grotesque travesty of manhood – dead men with fixed empty eyes and shiny yellow faces”.

During November 1917 Edward was transferred to the Italian Front which pleased Vera as, in comparison to the Western Front, this was considered a reasonably safe area of operations. In April 1918, during the German Spring offensive, Vera was ordered home by her father who informed her that her mother had suffered a breakdown and that it was her duty to return home and arrange home care for her mother who was currently in a Mayfair nursing home. Vera duly returned home and took charge of the household, but with a strong sense of resentment and a total disdain for the dull monotony of civilian life and the ill-informed views that most individuals safe at home in England held. In June Vera received the devastating news that Edward had been shot and killed by a sniper during a surprise attack against the British front line along the San Sisto Ridge. He was buried close to where he fell in the small cemetery at Granezza. Vera was distraught at this news, which must have seemed the cruellest of the many blows she had already endured. She eulogised her brother and continuously made public suggestions that Edward had died in an act of unrecognised heroic valour, a fitting epitaph for a bearer of the Military Cross. Sadly, this was to lead to yet more heartbreak, as many years after the event (1934) Edward’s Colonel, Charles Hudson VC, feeling “grossly traduced” by Vera’s claims of her brother’s valour, told her that he had, in fact, been under threat of court-martial for suspected homosexual activities and that in order to avoid the shame of this had, in all likelihood, gone into battle deliberately seeking to be killed, Hudson’s ire is perhaps understandable given that he was the holder of a Victoria Cross and that male homosexuality was not only illegal but also a social and moral stigma back in those days and viewed in military terms as being tantamount to treason whilst also inciting indiscipline amongst the troops. However his revelation, however justified in his eyes, was cruel, unnecessary and frankly unworthy of an officer and a gentleman. It seems beyond coincidence that Vera’s father, Thomas, who had never really come to terms with the death of his son, chose to commit suicide the following year in 1935.

Having broken her contract in returning home without authorisation Vera was not allowed back to France and was forced to endure the same routines as the trainee VAD’s whilst working as a nurse back in England and it was here that she, along with the rest of the nation, received news of the Armistice in November 1918.

In 1919 Vera returned to Somerville College and announced her intention to change her study course from English to History. This decision was prompted by her wartime experiences and she hoped that in studying history she could; “…understand how the whole calamity (of the war) had happened, to know why it had been possible for me and my contemporaries, through our own ignorance and others’ ingenuity, to be used, hypnotised and slaughtered”. Taking the same course in Modern History was Winifred Holtby, who both physically and temperamentally was the complete opposite of Vera. Vera resented her youthful vitality and felt somewhat bitter towards her younger Somerville contemporaries in general at what she regarded as their insensitivity to the events of the war. They in turn were irritated by her obsessive preoccupation with the war and at being made to feel guilty over an event in which most of them had been too young to serve in. This situation was not helped when Vera was humiliated at a Somerville debate on the motion that “Four years’ travel are a better education than four years at a university”. Vera of course used her wartime experiences in this debate but was soundly beaten, the final act of treachery, as she saw it, occurring when Winifred (the very person who had persuaded Vera to raise the motion) delivered a witty and damming indictment of Vera’s superiority towards those who had not shared her experiences. Vera’s humiliation was deeply felt, but Winifred’s belated recognition of Vera’s emotional fragility led to an unexpected and deep friendship that was to last until Winifred’s untimely and young death in 1935.

In 1919 Vera returned to Somerville College and announced her intention to change her study course from English to History. This decision was prompted by her wartime experiences and she hoped that in studying history she could; “…understand how the whole calamity (of the war) had happened, to know why it had been possible for me and my contemporaries, through our own ignorance and others’ ingenuity, to be used, hypnotised and slaughtered”. Taking the same course in Modern History was Winifred Holtby, who both physically and temperamentally was the complete opposite of Vera. Vera resented her youthful vitality and felt somewhat bitter towards her younger Somerville contemporaries in general at what she regarded as their insensitivity to the events of the war. They in turn were irritated by her obsessive preoccupation with the war and at being made to feel guilty over an event in which most of them had been too young to serve in. This situation was not helped when Vera was humiliated at a Somerville debate on the motion that “Four years’ travel are a better education than four years at a university”. Vera of course used her wartime experiences in this debate but was soundly beaten, the final act of treachery, as she saw it, occurring when Winifred (the very person who had persuaded Vera to raise the motion) delivered a witty and damming indictment of Vera’s superiority towards those who had not shared her experiences. Vera’s humiliation was deeply felt, but Winifred’s belated recognition of Vera’s emotional fragility led to an unexpected and deep friendship that was to last until Winifred’s untimely and young death in 1935.

After they both graduated in 1921, they set up home together in Bloomsbury, where they set about fulfilling their literary ambitions. Winifred was warm, generous and gregarious, whilst Vera could be moody, brooding, serious and a little pompous. The result was that they helped each other through all aspects of their lives in a relationship that was to be mutually satisfying and beneficial. The perfect Yin and Yang, so to speak. It is in this period that Vera’s feminism is given a universal voice, both in her writings and in her personal beliefs, becoming rather zealous in her determination to further the ambitions and achievements of women in general. She wrote; “My great object is to prove that work and maternity are not mutually exclusive”. A viewpoint that sadly, nearly 100 years on, some men still find difficult to accept. As writers Brittain and Holtby made decisive influences on each other’s works, with both being responsible for a number of fine literary pieces including the bestselling masterpieces; Testament of Youth, by Brittain and Holtby’s South Riding.

Vera married the academic George Catlin in 1925 but still maintained her close links with Winifred who moved into the London home set up by Vera and George becoming the third member of the household. Vera and George moved to America after George became a professor at Cornell University but Vera found it difficult to settle in America frequently returning to London and Winifred. After the birth of their children, John and Shirley (Williams), Vera moved back to London permanently with Winifred becoming an honorary aunt to Vera’s children. This was a situation that George resented and found deeply humiliating, writing; “You preferred her to me”. Vera had remarked to Winifred that; “Much as I love my husband, I would not sacrifice one published article for a night of sexual passion”. George’s marriage to Vera had been prompted by infatuation and it must be said that he must have known what he was letting himself in for, but one must have a certain amount of sympathy for his situation. Firstly Vera refused to change her name, for the simple reason that it was her name, so why should she be forced to take anybody else’s? The highlight of their honeymoon was a visit to Italy where Vera “introduced” George to her brother Edward. Taking roses from her wedding bouquet she took George up to the heights of the Asiago Plateau to watch her place them on Edward’s grave. This was followed by a “semi-detached” marriage where the company of Winifred Holtby seemed far more important to Vera than that of her husband, Vera even writing a letter to the unmarried Winifred during her honeymoon which stated that just one sexual encounter “would go as far as you ever needed”. Roland was continually referred to in impassioned reminiscence by Vera as a glamorous, heroic figure, despite the fact that they had met for a total of only 17 days, much of their relationship being conducted by letter. All of this, combined with the knowledge that Vera considered that not only the best of Britain’s youth lay in a foreign field but the second best also, must have been very hard to endure. George, like Vera, was a committed pacifist and also agreed with a lot of her feminist views, which possibly explains why, despite their many difficulties, their marriage matured, mellowed and survived until Vera’s death in 1970.

Testament of Youth was published in 1933 and, after Winifred Holtby’s early death through Bright’s disease in 1935, Vera’s biographical tribute to her; Testament of Friendship was published in 1940.

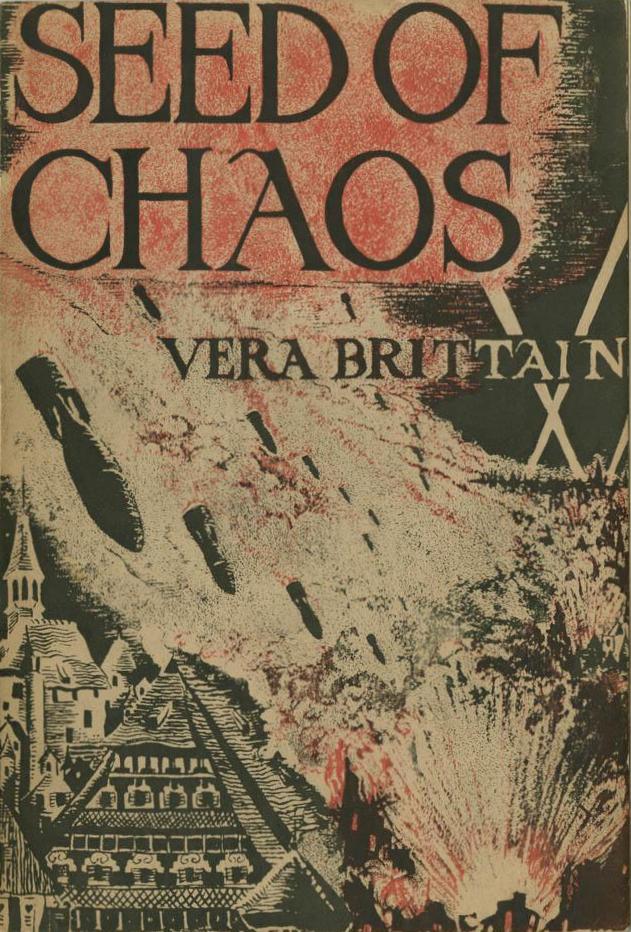

Vera’s passionate stance on feminism and pacifism continued throughout the rest of her life, campaigning for the Peace Pledge Union, CND, Anti-Apartheid and independence for colonised countries. Vera was always forthright and brave in her convictions, risking condemnation by publishing Seed of Chaos: What Mass Bombing Really Means in 1944, a work that criticised the mass bombing of militarily unimportant German cities. The public response was, in the main, abusive, but Vera’s reputation was restored when it became known that her name was entered in the Gestapo’s “Black Book”, a list of people to be arrested after the invasion of Britain. This was of course a perverse viewpoint as Vera was always a patriot, but her ideals of pacifism transcended national boundaries. As she wrote whilst serving as a VAD; “A dying man has no nationality”.

Vera’s passionate stance on feminism and pacifism continued throughout the rest of her life, campaigning for the Peace Pledge Union, CND, Anti-Apartheid and independence for colonised countries. Vera was always forthright and brave in her convictions, risking condemnation by publishing Seed of Chaos: What Mass Bombing Really Means in 1944, a work that criticised the mass bombing of militarily unimportant German cities. The public response was, in the main, abusive, but Vera’s reputation was restored when it became known that her name was entered in the Gestapo’s “Black Book”, a list of people to be arrested after the invasion of Britain. This was of course a perverse viewpoint as Vera was always a patriot, but her ideals of pacifism transcended national boundaries. As she wrote whilst serving as a VAD; “A dying man has no nationality”.

Testament of Youth at over 600 pages in length is, it must be said, no light read, but the effort is worthwhile. Covering the period 1900-1925 It is, as one would expect, at its most powerful during the war years and is greatly enriched by Brittain’s vocabulary and writing style which vividly draws a picture in the mind of the horror and futility of war. The book gives a voice to the wartime role of women, something of a rarity amongst the multitude of wartime literature that had been written by men, most of whom had been soldiers whose experiences had inevitably been confined to a small sector of the front. At the time of writing this first part of her autobiography Vera had become a prominent post-war campaigner for equal rights for women in the workplace and within marriage and she was determined that women’s experiences in war should also be recognised. It should also be remembered that it would have been very easy for Vera and many other VAD volunteers to have stayed at home and been patriotic, but they chose to throw themselves into a world that would have been totally alien to them. Indeed by Vera’s own admission she didn’t even know how to boil an egg when she volunteered for service. Her courage, like many of her fellow volunteers at this time, was probably bolstered by a sense of duty and patriotism. This illusion of honour and glory in war was soon to be shattered and, like many of her generation, Vera’s wartime experiences shaped the destiny of her beliefs for the rest of her life. Testament of Youth is, as Vera described, a; “…passionate plea for peace” showing “without any polite disguise, the agony of war to the individual, and its destructiveness to the human race”.

If the book is a little long for some tastes then try watching the BBC’s acclaimed adaptation from 1979. Vera Brittain is played by the marvellous Cheryl Campbell, who gives a stunning and mesmerising performance in the title role for which she won a richly deserved BAFTA for best actress. It covers the years 1913-1925 and remains faithful to the book, whilst concentrating on the war years where it to is at its most moving and powerful. If anybody fails to be moved by Testament of Youth then they have a very hard heart indeed.

Vera Brittain has been described in somewhat ungenerous terms by some of the people that met her, with self-important and an intellectual snob being two of the milder criticisms levelled at her. St. John Ervine believed he was exercising restraint when he wrote to Vera stating; “…your sense of humour is not, I should say, your strong point”. Given the fact that by 1918 she had lost her first great love, her two dearest friends and her brother, it is something of a miracle that she was able to function at all. All of this was of course compounded in 1935 when she lost her dearest friend, Winifred, and had to cope with the suicide of her father. In a sense Vera’s war never ended and her experiences form the inspiration for a large proportion of her literary works. Her tireless and brave work for peace, even in the face of hostility, is inspirational and she remained indefatigable in her pursuit of equality for women. Whatever perceived faults she may or may not have had the world would certainly have been a poorer place had she not lived. Even with a recent renaissance of her most famous literary work Vera Brittain, despite her prodigious output as a writer and as a high level campaigner on many prominent issues, remains relatively unknown to most people (When I mention her name to otherwise intelligent people the usual response I get is; “who”?). Let us hope the anniversary of WW1 and the upcoming film version of Testament of Youth will give her remarkable life story the prominence it deserves and allow a new generation to ponder the injustice and true horror of war.

One has to wonder how many Vera Brittain’s do there need to be before we finally learn the lessons of futile and unnecessary conflict.

The Testamant of Youth film will be released in late 2014 as part of the First World War commemorations. Swedish actress Alicia Vikander will portray Vera and Game of Thrones’ Kit Harington her fiancee Roland. Vera’s parents will be played by Emily Watson and Domnic West, Alexandra Roach will play Winifred and Anna Chancellor will play Mrs. Leighton.

Further Reading:

Brittain, Vera M. Verses of a V.A.D. (1918)

Brittain, Vera, Bishop, Alan (editor) Chronicle of Youth: Great War Diary 1913-1917 (edited 2002)

Bishop, Alan, Bostridge, Mark (editors) Letters from a Lost Generation: First World War Letters of Vera Brittain and Four Friends (edited 1998)

Brittain, Vera Testament of Experience (1957)

Brittain, Vera Lady into Woman (1953)

Brittain, Vera The Women at Oxford: A Fragment of History (1960)

Brittain, Vera Testament of a Peace Lover: Letters from Vera Brittain (edited 1988)

Brittain, Vera One Voice: Pacifist Writings from the Second World War (edited 2005 with a foreword by Shirley Williams)

Brittain, Vera, Bostridge, Mark (editor) Because You Died: Poetry and Prose of the First World War and Beyond (edited 2010)

Neil Kemp is a keen and passionate amateur historian and prize winning photographer who lives in Margate, on the North Kent coast in the United Kingdom. Before retiring he worked both with and at Margate Museum, overseeing budgets on a number of historical projects.