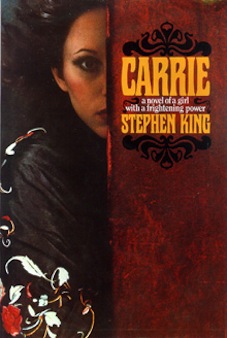

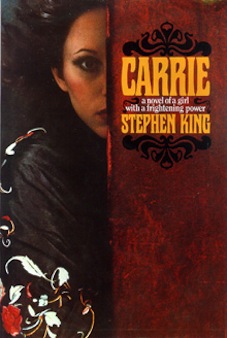

Carrie is Stephen King’s classic 1974 horror novel, his first published novel, filmed by Brian De Palma in 1976 and starring Sissy Spacek. It tells the story of Carrie White, a teenage girl, kept in a state of ignorance and fear by her mother – a religious zealot whose brand of hellfire Christianity borders on mania. Tormented by other high school students for her naivete, yet gifted with powerful and uncontrolled telekinetic powers, powers burgeoning as Carrie approaches womanhood. Pranked by her fellow students into thinking she will be prom queen, instead of being crowned buckets of pig’s blood are dumped on her, her humiliation, shame, fear and rage unleash telekinetic fury, and she brings the school crashing in ruins upon innocents and perpetrators alike. Not only does the story tap the mundane but seemingly all consuming fears of teens coming of age, it also invokes a primal fear of blood, indeed a taboo fear of menstrual blood. Torment, fear, rage and blood; in Carrie’s revenge we perhaps see echoes with the mass school killings usually enacted by marginalised young male outsiders. And yet we never lose sympathy for Carrie. She is herself an innocent, tormented beyond endurance, the destruction she wreaks, beyond her control.

Carrie is Stephen King’s classic 1974 horror novel, his first published novel, filmed by Brian De Palma in 1976 and starring Sissy Spacek. It tells the story of Carrie White, a teenage girl, kept in a state of ignorance and fear by her mother – a religious zealot whose brand of hellfire Christianity borders on mania. Tormented by other high school students for her naivete, yet gifted with powerful and uncontrolled telekinetic powers, powers burgeoning as Carrie approaches womanhood. Pranked by her fellow students into thinking she will be prom queen, instead of being crowned buckets of pig’s blood are dumped on her, her humiliation, shame, fear and rage unleash telekinetic fury, and she brings the school crashing in ruins upon innocents and perpetrators alike. Not only does the story tap the mundane but seemingly all consuming fears of teens coming of age, it also invokes a primal fear of blood, indeed a taboo fear of menstrual blood. Torment, fear, rage and blood; in Carrie’s revenge we perhaps see echoes with the mass school killings usually enacted by marginalised young male outsiders. And yet we never lose sympathy for Carrie. She is herself an innocent, tormented beyond endurance, the destruction she wreaks, beyond her control.

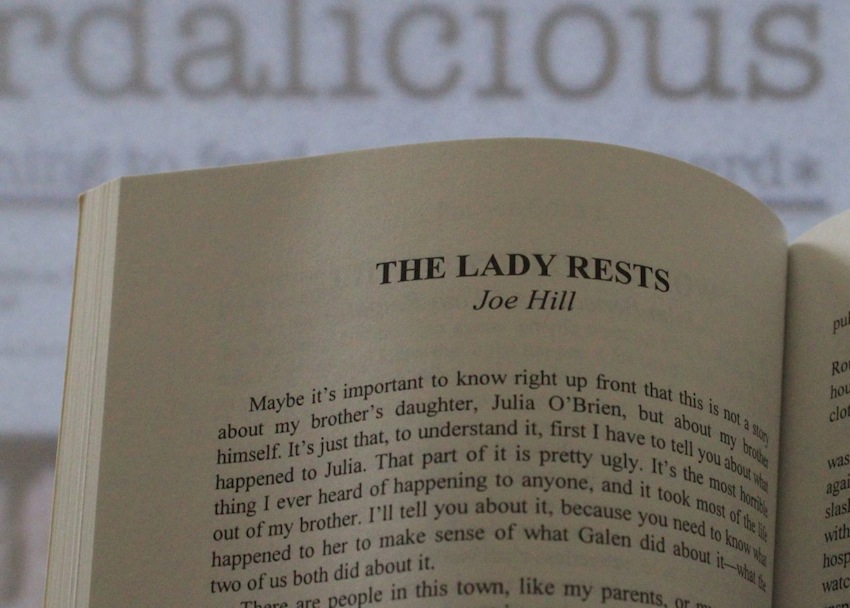

Joe Hill’s The Lady Rests is similarly the tale of an innocent teenage girl, tormented beyond endurance. It might be going too far to say this is a story without a single redeeming feature. Rather, it is deeply flawed. Joe Hill himself seems to have disowned it; it doesn’t appear in his bibliography. It was Joe Hill’s first professionally published work, appearing in volume VII of the small horror magazine Palace Corbie,(Merrimack Books, Lincoln, NE, 1996) before it was known that he was the son of horror grandmaster, Stephen King. Hill took his pseudonym from the Swedish-American labor activist and song writer, Joel Emmanuel Hägglund – who Anglicized his name to Joe Hill, and was executed for murder, probably unjustly, in 1915.

There is a humanity to King’s characters, even when flawed, even when committing evil. Not so with the characters in Joe Hill’s The Lady Rests. They are caricatures, mere cyphers, there to enact events. Even the title, on which the piece ends, seems glib, dismissive.

There is a humanity to King’s characters, even when flawed, even when committing evil. Not so with the characters in Joe Hill’s The Lady Rests. They are caricatures, mere cyphers, there to enact events. Even the title, on which the piece ends, seems glib, dismissive.

It is the story of a teen girl, Julia O’Brien, in many ways the complete opposite of Carrie White. From the brief interactions with her father, she is knowing, playful, flirtatious, confident. Julia is kidnapped, tortured and raped, essentially that is where her story ends. She is a marionette on which is enacted brutality. Hill’s story hangs on her determined attempts to kill herself; both acts of violence, the kidnapping and attempts at suicide, spelled out in graphic, gratuitous detail.

Both Julia, and the sadistic violence perpetrated against her, are dismissed before we know anything of either. Maybe it’s important to know right up front that this is not a story about my brother’s daughter, Julia O’Brien, but about my brother himself. The opening paragraph introduces the characters, and sets things up for what might be a tale of revenge. Hill continues. It’s just that, to understand it, first I have to tell you what happened to Julia. That part of it is pretty ugly. It’s the most horrible thing I ever heard of happening to anyone, and it took most of the life out of my brother. I’ll tell you about it, because you need to know what happened to her to make sense of what Galen did about it – what the two of us both did about it.

What follows is a few lines about the desire for revenge, which goes some way to reinforcing our expectations, What they want, what will satisfy them, is some brutally kinetic act, that crushes whoever it was that took her and ruined her. and how, in the end, rather than payback, their is some relief, Not hope, but relief. There is a recounting of the kidnapping, as described by a witness, a touch of forensic detail. Then a brief but brutal, matter-of-fact account of what was done to Julia. There is something salacious about the clinical tallying of the violence committed against Julia. While it may have been necessary for us to know what happened to Julia, the only point of the graphic description of the way the wires used to tie her cut into her flesh, and similar details, is the titillation of sadists. As we have known at least since 1931, when Boris Karloff’s monster in James Whale’s classic film of Frankenstein throws the little farm girl into the lake, censors who thought child murder too gruesome, not showing something, leaving it to the imagination, can in fact be more horrifying.

Perhaps it would have been better for us to know Julia herself. In what at first seems a poignant moment of domestic humour, the narrator, her uncle, Oliver, describes the last time he saw Julia, just before the kidnapping. Julia, just turned 15, interrupts her parents and uncle as they watch a basketball game. She comes into the room still wearing her soccer uniform and stands in front of the TV. She attempts to get a dollar from her father for every time she can keep the soccer ball from hitting the floor. “Come on you stingy old man…I’m going to the mall tonight. Cough up. I need some bread. Give me enough for the movies.”

Her father strips off his shirt and counters that she should pay him for every time he can make a farting noise with his hand under his armpit, All the time, Galen stared directly at Julia, his round face calm, almost contemplative, pale hairy belly sagging over his belt. After he had been going a while, Julia plopped down on the couch beside him.

“That’s four bucks you hypothetically owe me,” he said. He casually offered her his bottle of beer, Julia took it and swallowed some.

There is something a little uncomfortable, a little perverted, in this negotiation for money between precocious daughter and shirtless father, who then share a beer. “Maybe you help me with some hypothetical work out in the tool shed later, and I’ll let you off. Hell, I might even loan you a little extra.”

The play of psychology here has a certain depth. The characters, however, don’t quite ring true. Julia seems somewhat cliched, and more like a precocious 12 year old than a girl approaching her senior years in high school. Her father seems unsophisticated for a real estate professional, her uncle, a doctor, neither speaks nor reacts in a way that seems informed by medicine.

After being left for dead, after surgery and recovery, Julia remains both psychologically and physically damaged. Unable to walk without crutches, unable to talk because of her injuries. But even after she healed, she was non-verbal, and most of the time had about her the empty-headed quality of someone in a morphine-stupor, with only the eyes open to give the illusion of consciousness…You could see it in the way her face hung with an idiot slackness. Her uncle wonders, guiltily, if it would have been better if she died. Julia seems to have withdrawn into a kind of self-imposed autism, only reacting – and then with screams and violence – when somebody touches her.

After some time at home, she seems to have recovered a little. Her mother kisses her goodnight without raising a violent reaction. A little later her parents find she has dragged her way to the bathroom cabinet and back and is attempting to kill herself by methodically taking an overdose of pills. When they try to stop her she fights like a trapped animal.

Again, months pass, Julia remains in her stupor. A state of hopelessness also seems to effect her parents. Julia again attempts suicide, this time violently jabbing broken glass into her throat. By chance Oliver manages to stop her, and thinks he sees something of the old Julia in her eyes, Those eyes had flashed at me, bright and not a bit insane, but scared and awake and desperate.

There is some discussion of putting her in a home, but they decide to wait for the therapy to work. This is where the story again fails, in crucial details, in credibility. What kind of therapy is there that can work on a girl who only emerges from almost catatonia to make violent bids at suicide? Why would any doctor, any relative, any medical authorities allow someone in such a state to remain at home, unsupervised? Especially when she tries again, this time to hang herself with bedsheets?

Finally Oliver arrives one day to find Galen on the porch. Galen tells him, she killed herself. Oliver attempts to go in, to check, to see if she is still alive. Galen stops him. “Even if her heart has stopped, it doesn’t have to be too late,” I said. “Galen, if you love your daughter, get of the way before I knock you down.”

“I helped her,” he said, quietly.

Galen describes the scene as Julia ties an extension cord around an overhead pipe, how he helps steady her. Helps her tie the knot. How for the first time she didn’t scream when he touched her. “She was the one, kicked the chair out. It took a long time, Ollie. I thought it would break her neck and kill her right away when she fell, but it didn’t. She was jerking on the cord and making choking sounds and she reached up a couple of times like she was trying to grab the noose. I stumbled away from her and for a second I stood in the door. I couldn’t listen to her, I turned my back on her – I turned my back on her – and I sat down in the doorway and covered my ears.”

Oliver pushes his way past Galen, finds Julia grasping at the cord, struggling, on tip toes barely taking her weight on the overturned chair. He grabs her, trying to help. Then sees her scars and pulls down on her legs, breaking her neck. When he comes out, he tells her father that she died instantly, that what he thought was choking was just muscle spasming. He convinces him.

“Don’t bullshit me,” he said, but his voice was soft and unsteady.

“No.”

“I don’t feel like I thought I would,” came his hoarse whisper. “I don’t even know how to say – what this is – what this feels like. Is that crazy? I keep remembering – when it was over, I was glad, you know, it seemed like – I just keep remembering that.”

“She needed not to hurt anymore. You both did. That’s what she needed.”

Carrie weaves together diverse threads, religious mania, telekinesis, teen crises and fear and power into a whole that resonates. Carrie White is victimized, but her fear and fury and blood unleash power that takes her beyond victim to something akin to a force of nature. Julia O’Brien, who in some ways seems a response to Carrie, is only ever a victim. She is under the control of her father, perhaps performing for her father and uncle, kidnapped, controlled, used, tortured by unknown perpetrators, she becomes barely human, like one of those Japanese ghosts, animated only by remnants of destructive rage, her fury turned inward, so much so that her father and uncle, satisfying their own needs, at her behest, become her killers.

The Lady Rests bludgeons us with fears. Kidnap, rape, crippling injury, mental trauma, suicide and failed suicide, euthanasia and unsuccessful euthanasia. It lacks the essential mystery, the sense of the unknown that gives horror its thrill. This is horrific without horror. It approaches crime drama, but fails to follow through on the story of revenge suggested in the opening set up, which could have made it more than the sad and gruesome thing that it is. Something with suspense rather than sickness. It seems merely clumsy, not an attempt at a clever twist that has gone awry. Perhaps it is something new? Litany of cruelty as a genre? It has a certain emotional intensity. It may provide stimulus for voyeurs of mundane barbarities. For the rest, it is perhaps better left uncatalogued.