Much of our perception of Anne Boleyn has been shaped by the written word – from contemporary historical accounts to the dark portrait painted by her enemies. The Anne Boleyn Papers examines Anne’s ebb and flow of fortune in the words of those who knew her, from letters in her own hand, to the letters of a love-struck Henry VIII; from the poetry of Thomas Wyatt to the dispatches of the Imperial Ambassador Eustace Chapuys; from the pen of Cardinal Wolsey’s servant to the blatant and compelling slander of Nicholas Sander.

Much of our perception of Anne Boleyn has been shaped by the written word – from contemporary historical accounts to the dark portrait painted by her enemies. The Anne Boleyn Papers examines Anne’s ebb and flow of fortune in the words of those who knew her, from letters in her own hand, to the letters of a love-struck Henry VIII; from the poetry of Thomas Wyatt to the dispatches of the Imperial Ambassador Eustace Chapuys; from the pen of Cardinal Wolsey’s servant to the blatant and compelling slander of Nicholas Sander.

The Anne Boleyn Papers provides a comprehensive and important collection of contemporary sources and a paper-trail of influential writing that formed the myths and fuelled the centuries of debate surrounding one of England’s most controversial and enigmatic queens. Historian Elizabeth Norton joins us to discuss how the written word has created Queen Anne Boleyn.

Can you tell us about the idea behind the Anne Boleyn Papers?

There have been so many books written about Anne Boleyn that I wanted to show readers where the information comes from. For historians, the sources (along with archaeological evidence) are the tools for writing about and understanding the past. The Anne Boleyn Papers is, effectively, a biography of Anne, but in her own words, those of her contemporaries or slightly later writers. I tried to keep my own words or interpretation to a minimum and wanted to let the sources speak for themselves.

You have been researching Anne and her family for a number of years now. Looking at how fragmentary some of the sources are can you tell us what it is like to research such a controversial figure like Anne with so few resources?

Although there are seemingly few resources for Anne, she is actually much better covered than a lot of her contemporaries. Bessie Blount, for example, who was an almost exact contemporary of Anne, has left only one scribbled margin note in a manuscript as a record of her own words. Jane Seymour, with the exception of formal letters as queen, has also left very little account of what she actually said or thought.

So, in that sense, we are actually lucky with what survives of Anne. We are able to look at her personality to some extent. However, there are large gaps in the sources and it is never possible to actually know her, something which does make writing about her and researching her difficult. Anne is a popular figure and everyone has their own idea of what she was like. It can be hard to ignore your own personal view of Anne to read the sources dispassionately.

You’ve included a fairly disparate collection, including some of the really negative writings about Anne and even some letters that are considered forgeries. Why did you think it was important to include some of these accounts?

I think Anne can often be a really polarising figure – a lot of people really love her (even five centuries after her death). Equally, many people see her as the ‘other woman’ and someone who essentially got what they deserved. You only have to look at the two conflicting accounts of Nicholas Sander and George Wyatt to see that this diversity of opinion was well-established. In fact, even during her lifetime there were people who loved or hated Anne Boleyn. She inspired strong feelings.

It is really important to me to try to move away from stereotypes when I am writing a biography. At the end of the day, Anne was a real woman – neither wholly good nor wholly bad. I wanted to try to show this in the sources I collected, which is why I included the negative as well as the positive. I also think it is important to include all the letters, even if I think they are forgeries. The two letters, supposedly written to Anne by Henry are, in my opinion, likely to be forgeries – but this is just my opinion. I didn’t want to impose on the reader, I wanted to let the sources do the talking. There is one letter which purports to be from Anne and which deals with her concern that someone was feeding the chickens at Hever while she is at court. I think everyone would agree that this is a forgery, but that wasn’t always the case and this is the reason why I have included it. Even this letter has something to say about Anne – albeit clearly not from her own pen!

Are there any particular sources you think are overlooked?

Are there any particular sources you think are overlooked?

Although it is well known, I think that Cavendish’s Life of Wolsey could be better understood in relation to Anne. It is the source for Anne’s early relationship with Henry Percy, with Cavendish seeing this as the catalyst that caused Anne to bring about Wolsey’s ruin. What I think is fascinating is that Anne was able to square up to and try to bring down Cardinal Wolsey who was, of course, the second most powerful man in England. This gives a measure of her confidence and also her certainty of the king’s affection. It also shows her political acumen and the fact that she was able to act as a faction leader. I think this source benefits from close reading for those studying Anne Boleyn, although it is often overlooked in favour of the more obvious sources which cover a similar picture in Anne’s life, such as Henry VIII’s love letters.

Nicholas Sander’s Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism is probably one of the most infamous written attacks on Anne Boleyn. What sort of impact do you think Sander’s work has had on Anne’s memory?

Sander is certainly the leading source of the rumours that Anne had six fingers, as well as various other ‘deformities’ which would seemingly have made her very unlikely to attract the king. His claims that Anne was sexually voracious have always been very influential, although I’m not sure that anyone believed that she was actually the daughter of Henry VIII.

Sander wrote during the reign of Elizabeth’s daughter and was writing from a very different world to the one that Anne had lived in. Although she is often characterised as interested in religious reform (which she was), this is not actually any guarantee that Anne would have been a Protestant in later life. Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, who is usually considered to be the leader of the religious conservatives later in Henry’s reign was also involved in religious reform. Both were humanist in outlook in the 1530s, and identities of ‘Protestant’ and ‘Catholic’ did not become crystallised until later and have very little meaning in England in the 1530s. Nicholas Sander, on the other hand, was a Catholic, writing during the reign of Anne’s Protestant daughter when Catholics were actively persecuted in England. He therefore wanted to denigrate Elizabeth. Anne – with her poor reputation due to the manner of her condemnation and death – was an easy target. He was influential because he was widely read and his comments on Anne were not intended merely as history – he was making pertinent political statements.

Is George Wyatt’s Life of Queen Anne Boleigne one of the earliest written attempts to clear Anne’s name?

George Wyatt wrote in response to Nicholas Sander towards the end of the sixteenth century and was certainly one of the earliest comprehensive accounts. He interviewed people who had known Anne, as well as using Wyatt family papers.

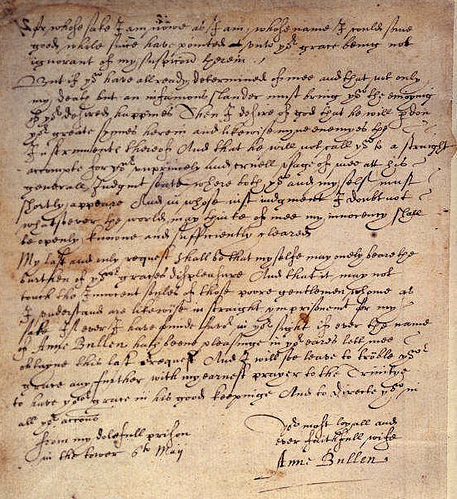

He is not the earliest writer to try to clear Anne’s name. Thomas Cranmer, in fact, writing to Henry at the time of Anne’s arrest, declared that ‘I am in such perplexity, that my mind is clean amazed: for I never had better opinion in woman, than I had in her; which maketh me to think, that she should not be culpable. Now I think that your grace best knoweth, that, next unto your grace, I was most bound unto her of all creatures living. Wherefore I most humbly beseech your grace to suffer me in that, which both God’s law, nature, and also her kindness bindeth me unto; that is, that I may with your grace’s favour wish and pray for her, that she may declare herself inculpable and innocent’. Although Cranmer did not exactly try to clear Anne’s name, he went as far as he dared, casting doubt on the crimes she was alleged to have committed.

The account of Alexander Ales, which was written in 1558 also attempts to clear Anne’s name, seeing her arrest as an attempt to discredit her on religious grounds. What I particularly like about this account is that he also gives us Cranmer’s private thoughts of Anne, with the archbishop declaring, when he heard of Anne’s execution, that ‘she who has been the Queen of England upon earth will to-day become a Queen in heaven’.

Which accounts do you think have been most influential in our picture of Anne?

That’s a tricky question! I think, unfortunately, Nicholas Sander has been influential in how Anne is perceived. However, George Wyatt’s account has been well known since the nineteenth century, as has Cavendish’s. I think popular culture also plays a big part in how we picture Anne – something which Susan Bordo has, of course, recently expertly written on!

Henry VIII’s love letters to Anne are arguably among the most well-known of contemporary sources on Anne and give us a fascinating insight into their relationship at the time, but what do you think the letters tell us about Henry himself?

The love letters are a revelation into Henry’s character. It is the only occasion in his life that we are actually able to see him in love – from his own perspective. The letters leave the reader in no doubt that Henry was devoted to Anne and that he loved her passionately. He was, after all, ‘stricken with the dart of love’. He was also desperate for some sign from Anne that his feelings were requited – she held all the cards. This can be seen in one letter where he wrote, ‘On turning over in my mind the contents of your last letters, I have put myself into great agony, not knowing how to interpret them, whether to my disadvantage, as you show in some places, or to my advantage, as I understand them in some others, beseeching you earnestly to let me know expressly your whole mind as to the love between us two’.

It is, unfortunately, a one sided conversation, and I would dearly love to see Anne’s responses. However, I think what the letters most clearly show us about Henry is that he was a human. He was passionately in love with Anne, taking the time to encircle their initials with a heart. He also involved her in his attempts to annul his marriage, writing to Anne of Wolsey, for example, something which shows that, to some extent, she was an equal partner in the relationship.

Which particular accounts of Anne have you personally found the most valuable or enlightening?

I actually really like Chapuys’ dispatches and have found them valuable and enlightening. They are the only sources that give daily accounts of what Anne was doing. They also allow us to hear her words and see something of her personality. There is obviously a massive caveat to this – Chapuys is highly biased and hated Anne. However, I do think that, without his interest in her, our knowledge of Anne would be a lot poorer.

Without Chapuys, we would have references to Anne in formal state papers and in the handful of letters that she wrote that survive. We have, of course, Henry VIII’s love letters, but otherwise our knowledge of Anne would be limited more to chronicles, as well as a few accounts of her by contemporaries. Personally, I think it is interesting to hear from Chapuys that Anne and Henry rowed publicly at court and that she could reduce him to tears – yes, Chapuys wrote this to portray Anne poorly, but it is also extremely enlightening in relation to the couple’s relationship. Similarly, Chapuys’ Anne was outspoken and independent. I think his accounts are enlightening and do not necessarily have to lead the reader to a negative view of Anne.

With thanks to Amberley Publishing.

Elizabeth is a British historian, specialising in the queens of England and the Tudor period. She was awarded a double first in her undergraduate degree at Cambridge and has a Masters degree from Oxford. She is currently working part time towards a PhD in history at King’s College, London. The rest of the time, she writes books and articles about the Tudors, including biographies of four of Henry VIII’s wives.

Find out more at www.elizabethnorton.co.uk

Follow Elizabeth on Twitter @ENortonHistory

Elizabeth Norton on Facebook

The Anne Boleyn Papers by Elizabeth Norton, published by Amberley Publishing 2013

Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII, caused comment wherever she went. Through the chronicles, letters and dispatches written by both Anne and her contemporaries, it is possible to see her life and thoughts as she struggled to become queen of England, ultimately ending her life on the scaffold. Only through the original sources is it truly possible to evaluate the real Anne. George Wyatt’s Life of Queen Anne provided the first detailed account of the queen, based on the testimony of those that knew her. The poems of Anne’s supposed lover, Thomas Wyatt, as well as accounts such as Cavendish’s Life of Wolsey also give details of her life, as do the hostile dispatches of the Imperial Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys and the later works of the slanderous Nicholas Slander and Nicholas Harpsfield. Henry VIII’s love letters and many of Anne’s own letters survive, providing an insight into the love affair that changed England forever. The reports on Anne’s conduct in the Tower of London show the queen’s shock and despair when she realised that she was to die. Collected together for the first time, these and other sources make it possible to view the real Anne Boleyn through her own words and those of her contemporaries.