The fact that the First World War ended on November 11th, 1918, is a well known and well documented event that is commemorated each year throughout the world. What is less well known is the fact that the last skirmish of the war took place some seven months later in the waters surrounding the Orkney islands of Scotland, when British sailors were ordered to fire on unarmed and non-threatening German seamen, many of whom had their hands raised in surrender whilst also displaying a white flag – an internationally recognised symbol of surrender.

The war in the mud and trenches of the Western Front ended at the appointed time under the terms of the armistice that had been agreed between all warring factions. The war at sea however, was a rather more protracted affair, with many British naval personnel not viewing Germany’s surrender as complete until the last ship of the German High Seas Fleet had consigned itself into British hands and lowered their colours in submission. This finally took place on the 21st November, when the German fleet was escorted into the Firth of Forth, before being moved, over the next couple of days, to anchorages in Scapa Flow, where they awaited their fate, which was to be decided at the upcoming Paris Peace Conference.

The German fleet’s passage into Scapa Flow had been a tense affair. Earlier, some forty Royal Navy battleships and cruisers had left the Firth of Forth and headed into the North Sea to rendezvous with the light cruiser, HMS Cardiff, which was escorting the German fleet into captivity. These ships were later joined by over 150 destroyers and other cruisers of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet in a show of force designed to ensure that Germany abided by the terms of the armistice in surrendering its fleet. David Beatty, commander-in chief of the Grand Fleet, had previously signalled all ships to be ready for action, such caution being considered necessary and well considered beforehand; indeed, any precipitous actions on such a tense meeting would certainly have been foolish.

The German High Seas Fleet was flanked on both sides, predominantly by ships of the British navy, but also by American battleships and French warships, an escorting force, in total, of over 250 ships, which now steamed either side of a six mile channel containing the German fleet.

This provided the spectacle of the mightiest gathering of warships in one place in naval history and, despite the photography of the time being extremely primitive by modern-day standards, some of the images recorded of this spectacle are truly breathtaking and give some idea of the scale of this operation.

As the last ships of the German fleet were escorted into the Firth of Forth, Beatty gave the rather terse signal that: “The German flag will be hauled down at sunset today and will not be hoisted again without permission”. Operation ZZ, or “Der Tag” (The Day), had passed off without incident and all that remained was for the victorious nations to decide the fate of the German High Seas Fleet, although few people present on this day could have envisaged that it would take a full seven months to resolve their fate, with the resulting tragic consequences for some of the German seamen who remained with their ships.

The British would have been happy to see the destruction of the German fleet, but France and Italy each wanted to acquire one quarter of the ships that were now interned at Scapa Flow and thus negotiations in Paris centred upon the distribution of the German fleet to the victorious powers rather than it being broken up. The majority of the German sailors who had brought the fleet into British waters had, after only a few weeks, been repatriated to their homeland, leaving behind only skeleton crews to man the 74 ships that were anchored at Scapa Flow. These seamen were not allowed shore leave or indeed to transfer between ships, even for visitations. Their rations, even when supplemented with food parcels from Germany, were of poor quality, bland and monotonous and, as the weeks dragged into months, their already poor morale declined still further and they became dangerously lax and ill-disciplined.

Although many British seamen felt a natural sympathy with their plight through the comradeship of sailors, who, regardless of nationality, always felt that they shared a common enemy – that of the sea itself – there were many who regarded them as cowards for being anchored in port for the last two years and relying on submarine warfare alone in continuing Germany’s war at sea. This, in some ways, was still thought of as rather underhand and not playing by the rules, which was obviously an outdated and essentially hypocritical viewpoint, but nonetheless prevalent amongst many seamen, regardless of rank, who had served their apprenticeships in what was already, within the passing of only a little more than a decade, a bygone era.

Throughout the course of the war Britain had maintained a numerical advantage of battleships and battlecruisers of around two to one. The Battle of Jutland, during the 31st May and 1st June, 1916, was to prove to be Germany’s last attempt to challenge Britain’s dominance at sea and, despite securing numerical advantages during the conflict, which gave credence to their claims of victory, it became apparent that Germany could not effectively challenge the might of the Royal Navy whilst being outnumbered to such an extent and the German High Seas Fleet returned to port, never again sailing out to confront the Royal Navy during the course of the war. Now completely unhindered, the Royal Navy’s blockade of Germany’s sea ports maintained a vice-like grip and was beginning to have devastating consequences as Germany, unable to trade by sea, now found its population being slowly starved into submission. Partly in retaliation and partly through necessity, as the only means available to strangle Britain’s supply routes at sea, Germany launched an intensive and unrestricted U-boat campaign during 1917. Initially, this proved to be extremely effective and a cause of great concern to the British government, with estimates that Britain had, at one point, less than four weeks supplies of food reserves. Jellicoe, the commander-in-chief of the Grand Fleet at this time, had stubbornly refused to consider the idea of supply ships travelling in convoy, as he considered this impracticable given the different capabilities of each vessel regarding speed and therefore regarded talk of convoys as an outdated idea from the age of sail. Necessity made him think again and, upon the introduction of protected convoys, losses were drastically reduced and the threat of Britain being starved into submission faded, although the introduction of compulsory rationing in January, 1918, was considered to be both prudent and necessary.

The Paris Peace Conference continued to drag on, with the weeks slowly turning into months. The Treaty of Versailles, the formal document ending the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers, was initially due to be signed in May, 1919, but this deadline passed and talks continued into June. An ultimatum was finally given to German negotiators, which stated that any failure to agree to the terms of the peace treaty would result in a resumption of hostilities, commencing with a crossing of the Rhine by Allied forces within 24 hours. On the 23rd June, Germany finally gave a formal declaration of acceptance, although the actual signing of the Treaty of Versailles would not take place until the 28th June. With somewhat mixed messages coming out of Paris during May and early June, the atmosphere at Scapa Flow remained very tense, with military confrontation becoming a real possibility. Both sides were now considering the implementation of plans that could, essentially, lead to this conclusion, but they were being considered for very different reasons. The Germans did not wish their fleet to fall into enemy hands, especially if the peace negotiations broke down, resulting in further hostilities, and had long-standing plans to scuttle the fleet if necessary. The British had drawn up plans to board and take control of the German fleet in order to prevent such an occurrence, but they secretly considered this to be the best solution to the crisis as it would not only deprive Germany of a formidable fighting unit, but also stop its distribution amongst Britain’s allies which would dissipate the Royal Navy’s current maritime supremacy.

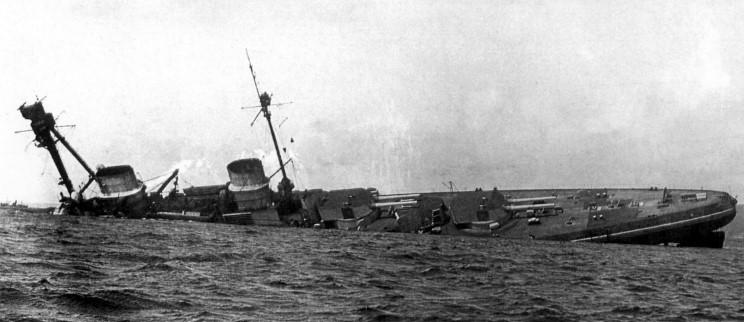

At 10.30, on the morning of the 21st June, Rear admiral Ludwig Von Reuter, the commander of the interned German fleet, gave the order for a seemingly innocuous message to be signalled from his flagship to all the other ships of the fleet. The message read: “Paragraph eleven. Confirm”. This was the coded command for the scuttling of the fleet and every German seaman now busied himself with this task; opening seacocks, portholes, watertight doors and hatches, whilst also raising the German flag. Von Reuter had chosen his time well, with the bulk of the British “guard ships” having left that morning for naval exercises.

When it became apparent what was going on a message of recall was sent out and sailors were dispatched from the two remaining British ships, the destroyers Vespa and Vega, to board the German vessels in order to try and prevent their sinking. They were issued with small arms and under orders to use deadly force if necessary to carry out this task, although by this time the vast majority of German seamen had abandoned their ships and were rowing away from them in small lifeboats. The British sailors who remained on board their ships were ordered to fire upon the men in the lifeboats as they had broken the terms of the armistice and their actions were thus interpreted as an act of war, effectively making them “fair game”. Some tried to row to shore, whilst others moved alongside British ships, wishing to be taken aboard, with their hands raised and white flags showing. Shamefully, the order was not revoked and firing continued, although even those perpetrating this action must surely have realised it could have no material bearing as to whether or not the German ships could be saved.

By the end of the day some 52 ships had been sunk by the Germans, with the British managing to keep the remainder of the fleet either afloat or successfully beached. Publicly, the British were outraged and regarded the scuttling of Germany’s fleet as a dishonourable and infamous action, in private however, they were rather content with the outcome as they had, from the outset, considered the destruction of the fleet as the best solution.

The majority of the sunken vessels were raised and broken up for profit during the 1920’s and 30’s, with all of the saved vessels either meeting the same fate, or being used as target ships and, in one case, serving a purpose in WW2 as a channel blocker at Scapa Flow.

Some small salvage operations have taken place after WW2, as the high quality metals, buried in their watery tomb, remained free from the effects of post-atomic radiation and were much sought after for use in sensitive scientific instruments. It has even been stated that it is very probable that a small part of the German High Seas Fleet currently resides on the Moon as many components of the American space programme contained metal obtained from its salvage.

Miraculously, only nine German seamen were killed during the scuttling, with a further sixteen being wounded. Whether this can be attributed to good fortune, poor marksmanship, or a reluctance to shoot to kill, will remain a matter of conjecture. What is undeniable is that this episode added a further postscript to the carnage of the previous four years and, whilst the casualty figures may have been low, the senseless and pointless nature of these deaths rivalled anything that had occurred during 1914-18. All the remaining crew members, including Von Reuter, were declared to be prisoners of war because of their actions and thus, at a stroke, this engagement could be justified as war rather than slaughter.

Eight of the German dead from this action lie in the graveyard at Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery, in the Orkney islands, with their names and the date of their deaths. This event, perhaps understandably, remains relatively unknown and forgotten. However, it was witnessed by a civilian artist, Bernard Finnegan Gribble, who painted a remarkable picture of this incident, entitled: Sinking of the German Fleet – Scapa Flow on Saturday 21st June 1919. This work literally painted a picture of that fateful day and ensured that, despite all efforts to defend the indefensible, a visual record of those events would remain – lest we forget.

by Bernard Finnigan Gribble ©Nick R. Gribble/National Museums Scotland

Neil Kemp is a keen and passionate amateur historian and prize winning photographer who lives in Margate, on the North Kent coast in the United Kingdom. Before retiring he worked both with and at Margate Museum, overseeing budgets on a number of historical projects.