The figure of the Witch, as a servant of Satan, ensorcelling men, sacrificing Christian babies and committing all sorts of cruel and lascivious atrocities, often while in the quite ordinary guise of harlot, stepmother, crone, as a subject for horror has been out of favour since the image of the good witch, the witch as herbalist and Earth mother in philosophies like Wicca rose in popularity in the 1970s.

The culture around witches changed so much that through the 80s and early 90s in conservative communities in the USA grizzly crimes were often ascribed to the ritual activity not of crones and seducers, but of teenaged boys, who surrounded by the theatrical trappings of the heavy metal music they listened to made easy scapegoats in the cultural madness of the “Satanic Panic”.

Fear of witches began in earnest in the late Middle Ages. Enduring sickness, famine, war and death without any apparent rational explanation in an age of superstition lead people to ascribe blame to those who were often already marginalized. Religious schism lead both Catholic and Protestant to repudiate each other’s belief, but folk traditions and the remnants of pagan practices, previously tolerated, also became a focus for the zealous with the urge to validate their own belief by stamping out heresy.

Publication of such tomes as the Malleus Maleficarum, (Der Hexenhammer in German) The Hammer of Witches which destroyeth Witches and their heresy as with a two-edged sword, written by German Dominican Heinrich Kramer, argued against those who denied the existence of witchcraft and tried to discredit them, it codified the ways of identifying and prosecuting a witch, argued that women were more likely to be witches, and extolled magistrates to conduct prosecutions. The Witch Hammer was actually condemned by the Catholic church in 1490, just three years after publication. Kramer was seen as something of a fanatic, he had been expelled from Innsbruck by the bishop after attempting a witch prosecution there. He undoubtedly felt vindicated when courts and local authorities through the 16th and 17th century took up his tome and pursued prosecutions. Where previously the Church had viewed witchcraft as erroneous belief in old pagan ways, and people found to be practicing witchcraft were punished with penance and perhaps a day in the stocks, it was the Malleus Maleficarum itself which bred fear and convinced people of the dangers of witchcraft and the evil of witches, and lead to increasingly brutal prosecutions and punishments.

Neither reformation of religion, advancement of Enlightenment philosophies, or changes to law saw a lessening of suspicion amonst the credulous. However the march of industrialization, the change from a religious agrarian culture to one of science and machinery finally lead to a change in attitudes. While William Blake decried the destruction of nature and the rise of the dark, Satanic mills, there is nothing more likely to counter superstition than the symmetry of a cast iron bridge, or the sight of a steam train propelling across the landscape in all the beauty of its reptitive mechanical process.

Even in puritanical America in Salem, a town made infamous for the conviction and execution of 20 people for witchcraft in the late 17th century, by the late 19th century a civil prosecution for witchcraft was dismissed out of hand. In 1878, apparently at the behest of Mary Baker Eddy, one of the founders of the Christian Science movement, one member of the sect, Lucretia Brown, prosecuted a former adherent with whom Eddy had fallen out, Daniel Spofford, accused of controlling her mind by use of malicious animal magnetism, or demonic mesmerism, a “mind crime” that employed an evil force, though now couched in scientific terms, akin to witchcraft. The case was sensibly dismissed out of hand as unprovable, but Eddy remained obsessed with the evils of malicious animal magnetism throughout her life, though the chapter Demonology was later dropped from the Christian Science book of doctrine, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.

Lucretia Brown’s lawsuit stated that Daniel Spofford

-

practices the art of mesmerism, and by his said art and the power of his mind influences and controls the minds and bodies of other persons, and uses his said power and art for the purposes of injuring the persons and property and social relations of others and does by said means so injure them.

-

And plaintiff further showeth that the said Daniel H. Spofford has at divers times and places since the year eighteen-hundred and seventy-five wrongfully and maliciously and with intent to injure the plaintiff, caused the plaintiff by means of his said power and art great suffering of body and mind, and spinal pains and neuralgia and a temporary suspension of mind, and still continues to cause the plaintiff the same.

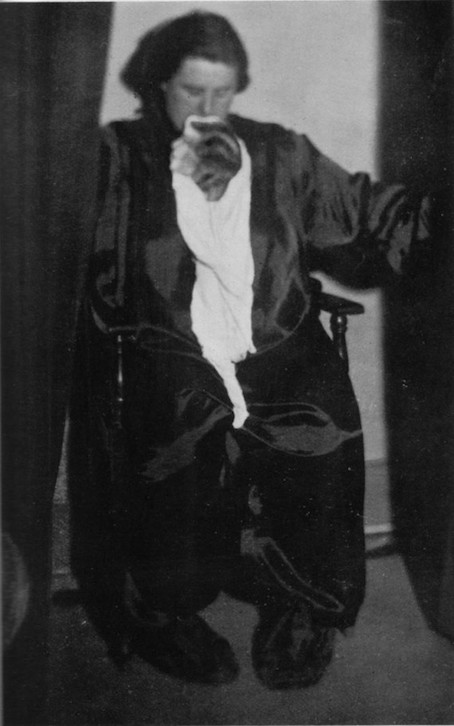

One of the last witchcraft cases in England is even more peculiar. Helen Duncan was a medium and seancer who had been prosecuted numerous times under the Witchcraft Act of 1735, for fraudulently pretending to cause the spirits of deceased persons to be present. Duncan and others in the Spiritualist business had no qualms about employing hidden assistants, mechanical devices and other theatrical techniques, one of her specialties involved vomiting forth ghostly ectoplasmic bodies, an effect she achieved by regurgitating cheesecloth. In 1941 she had revealed to a stunned audience that the spirit of a Royal Navy sailor had appeared to her, and told her of the sinking of the battleship HMS Barham. Information the War Office had yet to release. Later it was revealed that hundreds of people had been informed of the loss prematurely, Duncan had undoubtedly heard rumours of the sinking from one of these people, but her reputation as a genuine clairvoyant had been firmly established, so much so that the credulous believed her later arrest and conviction was to prevent her repeating other sensitive military information garnered from the spirit realm.

The 1735 Witchcraft Act was born out of Enlightenment rationalism, as a response to the witch frenzy of previous centuries. Like the earlier Church position, it assumed that there was no such thing as magic or witchcraft, and indeed made it a crime to claim that a person had magical powers, and even a crime to accuse someone of practicing witchcraft. It was used to prosecute fraudsters, charlatans and cheats, and as a remedy to the victimization of people under the previous Witchcraft Acts.

It was Henry VIII who in 1542 first made witchcraft a crime punishable by death, with the goods and chattels of those convicted forfeited to the Crown. Henry notoriously burned Elizabeth Barton, the mystic Nun of Kent for predicting the King’s Death, a crime under the Treason Act, an accusation he also used against Anne Boleyn when he wanted rid of her.

Treasonous adultery and procuring the King’s death by prediction seem quite ordinary in comparison to the crimes covered in The Witchcraft Act, which forbade on penalty of death;

… to use devise practise or exercise, or cause to be devysed practised or exercised, any Invovacons or cojuracons of Sprites witchecraftes enchauntementes or sorceries to thentent to fynde money or treasure or to waste consume or destroy any persone in his bodie membres, or to pvoke any persone to unlawfull love, or for any other unlawfull intente or purpose … or for dispite of Cryste, or for lucre of money, dygge up or pull downe any Crosse or Crosses or by such Invovacons or cojuracons of Sprites witchecraftes enchauntementes or sorceries or any of them take upon them to tell or declare where goodes stollen or lost shall become …

The act also removed the right to Benefit of Clergy, an old law which provided that anyone convicted of witchcraft would be spared hanging if they could recite three passages from the Bible. Provocations to unlawful love and the conjuration of sprites to find lost treasures seem born out of Henry’s own selfish and paranoid concerns, and after his death Edward VI repealed Henry’s Witchcraft Act just five years later.

While Elizabeth I’s An Act Against Conjurations, Enchantments and Witchcrafts of 1563 made it a felony punishable by death only in cases where the use of witchcraft, enchantment, charms, or sorcery resulted in destruction or death, lesser offences were punished by a prison sentence. It also removed witch trials from the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts, where purification through burning, rather than the arguably more merciful execution by hanging, was the practice. Given that she often had the notorious astrologer and reputed witch Dr John Dee at her court, it is not surprising that an era of religious tolerance extended to both the traditional folkcrafts an the more theatrical activities of the alchemists, astrologers and clairvoyants that entertained royalty.

The Scottish Witchcraft act of the same year took a somewhat harsher approach, practicing and even consulting with witches were capital offences, and with the accession of James I in 1604, An Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked spirits broadened the crime again, to cover invoking evil spirits or communing with familiar spirits; attributes of witches derived from The Witch Hammer.

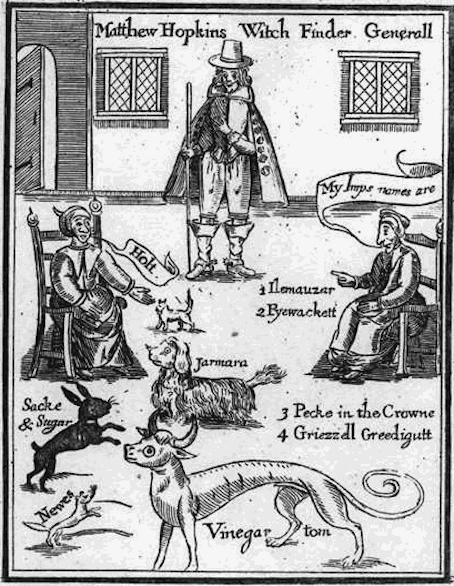

It was under these laws during the already fraught rule of Oliver Cromwell and the chaos of the English Civil War, that Matthew Hopkins, The Witch-Finder General, enacted a reign of terror that in three short years, from 1644 to 1647, saw over three hundred women hung or burned for witchcraft.

In the age of advancing scientific discovery, enlightenment philosophy, social reform, democracy, industrialization and the beginnings of a consumer culture, after the 1735 act, such beliefs seemed ridiculous, became reinterpreted through the prism of progress and became instead the fodder for fantasy and nightmare.

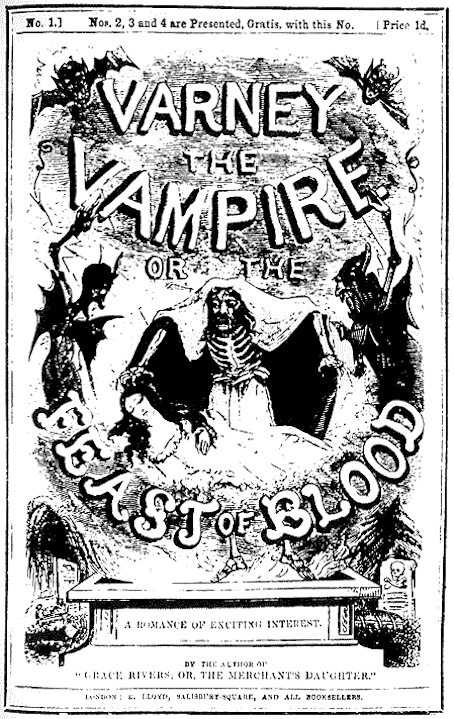

Thus was born Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case Of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture Of Dorian Grey, H G Well’s The Invisible Man, Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the high points of Victorian Gothic horror. The actual penny dreadfuls were serialized stories churned out weekly in pamphlets, sold for a penny, whose pages were crowded with lurid tales of vampires, werewolves, daring highwaymen and even the savagery and adventure of the wild west. Varney The Vampire, Sweeney Todd and even the larger than life tale of Dick Turpin appeared in the penny dreadfuls.

The 19th century had its own real life horrors as well. Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum with its depictions of the historical, the famous as well as the infamous opened in Baker Street in London in 1835. The terrors of the French Revolution were still fresh in the minds of the public. Reports from Tasmania of the escaped convict, murderer and cannibal horrified. Indian massacres and the Donner Party from the US shocked, as did tales of the uprisings of bizarre cults in the East and savage tribes in Africa. Horror seeming stalked all quarters of the Empire. At home, in the heart of London Jack the Ripper terrified. Credulity, curiosity and a new found freedom to investigate both spiritually and scientifically lead to a fascination with the supernatural that saw people from Arthur Conan Doyle to Queen Victoria participate in seances.

Out of this foetid fever dream of the ghastly, grim, exotic and bizarre it seems an odd, indeed a brave choice for the second series of Penny Dreadful to choose a coven of Satanic witches as foes. Having battled a plague of animalistic vampires in the quest to rescue his missing daughter Mina, Sir Malcolm Murray and Vanessa Ives and their companions are now threatened and manipulated by a sinister coven, servants of Satan, with designs on Miss Ives, who has had her own battles with Satanic possession, and may be the focus of evil intent, the culmination of an apocalyptic prophecy.

Even in the late 19th century, those destroyed by medieval Christian superstition were viewed as the victims, the witch-hunters themselves seen as misguided, if not outright evil. Witches after all now used scientific mesmerism and bell jars and galvanism to contact spirits, to allay fears and offer comfort. They used mystic powers and herbal knowledge to heal, not to hurt. Belief in the devil as a physical being, a force of evil in the world had waned, perhaps because of increasing scientific knowledge. The medieval universe with Earth at the center and the devil below in the underworld was not geocentric but diabolocentric. With the heliocentric universe and then increasing awareness of the vast firmament without a fulcrum, the devil had no where left to live; under the Earth burned not the fires of hell, but those of geology.

Current discussion about the era of the witch trials sees it as directly related to the repression of women, control and subjugation of bodies, of minds and of sexuality, a bizarre and oppressive regime enacted by men using psuedo-Christian mythology. The mythology of the Satanic had also moved on, from the lewd seducers and hags of the 16th century dancing around bonfires in pagan midnight ceremonies, to cabals of elites making ritual sacrifice for wealth and power, to dedicated cultists bringing about the apocalypse, to heavy metal teenagers pledging to the dark lord and committing violent atrocities for kicks.

Penny Dreadful could have easily succumbed to the lurid trappings of its Victorian gothic name sake, it could have indulged in the often theatrical shenanigans of American International or Hammer pictures from the 70s, it could have been even worse with the sexy, wisecracking Wiccans of contemporary urban fantasy.

Instead its witches are straight out of a 16th century woodcut; naked, bony and horrible, gruesomely marked by their dark master, controlled by a sinister and evil matriarch who metes out the severest punishment for any failure. By day they move easily through polite Victorian society, demure ladies attracting little attention. These Nightcomers, daughters of Satan are then contrasted with a woods witch, Joan Clayton, who lives in an ancient cottage on a storm wracked moor. She is no pleasant fairy godmother, but a hard and ancient crone, embodying the medieval myth of the hag with the reality of the kind of healer that was sometimes the victim of the witchfinders. Known as the Cut-Wife, she performs abortions for the young girls of the district, exploited by the local lord, sir Geoffrey Hawkes, but is nevertheless hated by the superstitious village folk. The contrast of witches unifies the mythology and the reality of the witch persecutions, and brings it into the present without glamour but with horrifying immediacy.

Compare two moments. Out on the moors, in the primitive agrarian backwater where superstition and a Feudal sensibility still holds sway, Evelyn Poole, the mother of witches, and Lord Hawkes, lead a lynch mob of villagers who seize Joan Clayton and after summary justice, tie her to the witch tree and burn her. Poole wants to destroy a rival, Hawkes, goaded by her, to seize Joan Clayton’s land. Dispossesion, the seizure of land was one of the prime motivations behind accusations of witchcraft since the creation of Henry VIII’s Witch Acts. Under a regime where the lord was often also the local magistrate, subjective and arbitrary laws were open to abuse. The land was given to Joan Clayton some two hundred years ago, apparently by Oliver Cromwell himself. There’s a curious back story we don’t find out much about. Would the puritanical old megalomaniac really have given land to a witch? Yes, he lead the Parliamentarians and finally put the last nail in the coffin of absolute Monarchical power in England, but then he essentially declared himself emperor, and oversaw one of the greatest periods of death, destruction and persecution in English history.

Meanwhile, in the city, a young couple with their new baby board an empty second class train carriage on London’s tube system. Surely one of the ultimate symbols of progress and modernity. They are stalked by Hecate, one of the grim and nightmarish witches. Again, in a twist on one of the classic witchcraft tropes she slaughters them and takes their baby. Not a Christian baby as such, but a modern, middle class baby, an aspirational baby. A symbol of hope, destroyed. Essentially, the witch takes our baby for her mother’s diabolical magic.

Why is it our baby? Because the young couple are passengers on a Second Class Carriage. In England, in 1891-2, the years in which these horrors occur, there were no Second Class Passengers.

Prior to 1844 the railways in England were a diverse collection of private and local operators running a complex system with different prices, rules, conditions and timetables. The ability for workers to travel was essential to the progress of industrialization. Carriages for workers were often little more than open flat beds with railings, overcrowded, unsafe and exposed to the elements. The Railway Regulation Act of 1844 established minimum standards and brought order to the system.

The “Stanhopes” the open cargo carriages in which workers could only stand up were abolished. The new legislation provided that at least one train carrying third class passengers should run each day, travelling in each direction on a line, stopping at every station, with seats for passengers and protection from the elements, with an average speed of not less than 12 miles per hour, an allowance for luggage and a fare of 1 penny per mile.

The railway magnates of the time balked at the prospect. Many continued to run inferior third fourth class services, as well as a token Parliamentary Train, which they would schedule at inconvenient hours, late at night or early in the morning. Their fear was that if conditions improved second class passengers would abandon the higher priced service for the cheaper third class.

Remember, it is not, as we may assume, the facilities of the carriage that defines the class, it is the condition of the passengers. In a society stratified along class lines, the mingling of the lower orders, the factory workers and miners and labourers, with the higher classes was seen as a threat to the very fabric of society.

The Midlands Railway defied their fellow capitalists and provided carriages with oil lamps and glazed windows to all passengers, in 1875 they abolished Second Class altogether. This wasn’t merely a rationalization of services, the lower orders in one fell swoop were being uplifted and put almost on a par with their betters. Sir James Allport, General Manager of the Midland Railway declared, “If there is one part of my public life on which I look back with more satisfaction, it is with reference to the boon we conferred on third-class travellers.” It wasn’t the struggle of the Labour movement and socialist unions that transformed English society, it was comfortable and affordable rail travel.

Society was outraged. The abolition of second class could have been seen as the demotion of an entire section of the population. However, with increasing prosperity and education across the society, the strict class lines of British society began to blur. Other railways relabeled Second Class carriages and by 1891, there were First Class and Third Class carriages, but no Second Class Passengers. In the show, Penny Dreadful, the slaughter of a middle class young couple, the kidnapping of their baby, occurs in a Second Class carriage because of its symbolic value. These are not Third Class Passengers, these are not First Class Passengers, these passengers represent us.

Of course some of you will say I am reading too much into this. Is it really a tale of the collapse of colonialism, the struggle between the old philosophies of religion and the new ones of science, the conflict between superstition and knowledge, a class struggle, the rise of the new middle class from working class origins, and their battle against secretive cabals of the powerful that want to drag the world back into primitivism, servitude, enslavement, and absolutist power, and is that really relevant today?

Is it rather just an incredible horror show, with clever, surprising reversals on familiar tropes, striking images and scenes, beautifully realized, intense performances from a stellar ensemble cast, where even the monsters struggle with their inner demons? Consider Sir Malcolm Murray, once the epitome of English Colonialism, transformed and haunted by his experiences, or Miss Ives (and amongst a stand out cast a riveting portrayal from Eva Green) a victim of demonic possession, but stronger, more resilient, more powerful because of it, or Frankenstein’s Creature, created by man and science, but broken, distorted, with an immense soul seeking after beauty, but forsaken, or his bride, created by Frankenstein for the monster, whom she finds repellant, but so beautiful that the creator falls in love with his creation. Traditionally, the Creature in insensate jealous rage tears her head off. Here things may play out a little differently. From a working class Irish prostitute dying of consumption, the bride is transformed into an elegant, demure English debutante. Well, until some inner compulsion, perhaps a memory of her former self, drives her to pick up a stranger and with the strength of a monster, strangle him. Whether that is a kind of suffragette reversal on the horrors enacted against women by Victorian men in general, as symbolized by Jack the Ripper, I’ll leave to your imagination.

Railways, witches, Satan and class struggle? I hear you scoff, but just remember, the biggest audience for Penny Dreadfuls were working class young men, riding Parliamentary Trains to their jobs in factories, and out of these dark, satanic mills, arose our consumer society in all its glory and excess.