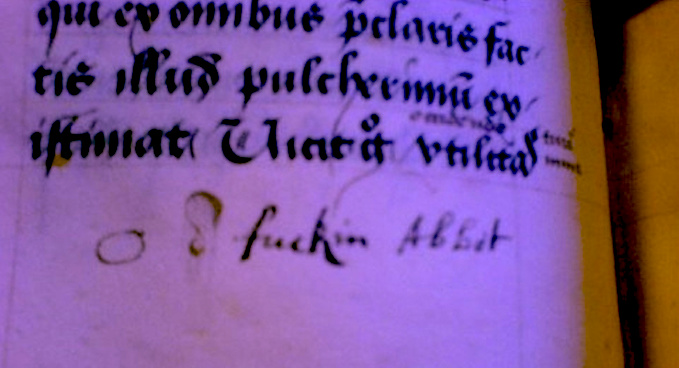

The first recorded use of the word in English occurs in a 1528 manuscript copy of Cicero’s epic work of moral philosophy, De Officiis. In the margin an anonymous monk has written, “fuckin Abbot”. It is not immediately clear whether the author refers to the apostate Abbot’s unwholesome sexual practices literally, counter to the miscreant monk’s vows of celibacy, or whether it is a more general, pejorative complaint.

There is an often stated but perhaps misheld belief that the usage of such words in their historical contexts were matter-of-act; neither rude, lewd, vulgar nor insulting. The jot, accompanied by a doodle of an eye or orifice, and an overlarge, sticking-out ear, in some ways disavows that notion.

Cicero’s text elucidates the issue further. De Officiis (On Duty or On Obligation), penned by the Roman politician and philosopher in 44BC after the fall of Caesar, is a treatise of moral philosophy, mainly concerned with public life, that looks at what is moral or honorable, what is advantageous or expedient, and what occurs when the expedient and the moral conflict. Book III, Chapter IV, Section 19, where our anonymous observer has made his comment;

For it often happens, owing to exceptional circumstances, that what is accustomed under ordinary circumstances to be considered morally wrong is found not to be morally wrong. For the sake of illustration, let us assume some particular case that admits of wider application — what more atrocious crime can there be than to kill a fellow-man, and especially an intimate friend? But if anyone kills a tyrant — be he never so intimate a friend — he has not laden his soul with guilt, has he? The Roman People, at all events, are not of that opinion; for of all glorious deeds they hold such an one to be the most noble. Has expediency, then, prevailed over moral rectitude? Not at all; moral rectitude has gone hand in hand with expediency.

“qui ex omnibus praeclaris factis illud pulcherrimum existimat. Vicit ergo utilitas honestatem?”

The text has been a justification for the expedient as a moral act ever since, studied by leaders of Church and State. Despite being the work of a pagan Roman, St Ambrose declared it suitable for use by the Church in 390AD. It was the moral authority through the Middle Ages. Catholic and Lutheran humanists referred to it, Henry VIII wrote “Thys boke is myne” in his childhood copy, it became a standard text in Westminster and Eton, in Cambridge and Oxford, and other English schools from the 17th century. Classical Republicans, Enlightened Absolutists, Liberal Philosophers and Rhodes Scholars found in it the ways and means to balance advantage and expedient action with a moral position constructed from the authority of the masses. If the people believe that an action carries no burden of guilt, that circumstances could make an expedient action into a noble one, such action is no longer immoral. The killing of a tyrant, executions, acts of war, enslavement, bigotry could all be justified. Cicero’s great failing is in assuming that the authority derived from the people was an absolute, that it could neither be wrong, nor subject to manipulation. Oration in the Senate is a far cry from the cynical manipulations of the mass media.

Our erstwhile vulgarian seems to have taken offence at this juncture, that a leader, who should lead by example, deriving moral authority from moral behaviour, has instead used a position of authority for self-advantage, and perhaps appealing to the classics as justification.

Like us, our forebears had many words for congress. John Florio’s Italian-English Dictionary of 1598, A Worlde of Wordes proffers several once vulgar but now archaic English synonyms for the Italian Fottere: To jape, to sard, to fucke, to swive, to occupy.

While Fottere is from the Latin futuere, the present active infinitive of futuō, it can also mean to swipe, to steal, and also to con or trick. To jape retains that meaning, to game, prank or joke, but has lost its sexual connotation. To sard, from the Anglo-Saxon verb seordan, to copulate, is now little more than a Wonder Soap, to get you whites whiter than white, swive is similarly of Anglo-Saxon origin, from swīfan, to move quickly, to revolve or swivel, and screw still carries both the sexual and the swindle, and while the physical origins of the term to occupy seem apparent, the use of the word in terms of current parlance gives an intriguing new meaning to political movements, such as Occupy Wall Street, or military ones, such as the Occupation of Gaza.

Fukka, Focka, Fokken and Ficken, from old Norwegian, Swedish, Dutch and German all suggest a Northern European origin, perhaps all coming together in English in a kind of etymological onomatopoeia, curiously enough, the combination with Abbot (from the Middle English abbot, from Old English abbat, from Latin abbās (father), from the Ancient Greek ἀββᾶς (abbâs), from Aramaic אבא (’abbā, – father) the head of an Abbey or Monastery), seems to be repeated, most aptly, at this moment in time, so far but still so close to when it was first inked.

Along with its counterparts, given their origins and contemporary meanings, transformed by time, use and history, a surprising relevance occurs. For a word, like a sedimentary rock or layers of archaeological detritus, still resonates with its original meanings.

To our treatise on the moral and the expedient in public life, the jottings of our derisive commentator, the image of an ear and an orifice, we might most appropriately add another term. While there is still some debate, most etymologists agree kuntō from the Proto-Germanic became kunta in the Old Norse, and from there a whole slew of variations in the other Germanic languages; kunta in Swedish, Faroese and Nynorsk, kunte in West Frisian and Middle Low German, conte in Middle Dutch, kut and kont in Dutch, kutte in Middle High German, kott in German, and perhaps cot in Old English, then spellings such as coynte, cunte and even queynte, in Middle English, which had little bearing on pronunciation. It seems in Chaucer’s time as spoken by The Wife Of Bath in The Canterbury Tales (1390), it may have been pronounced more like “quaint”

For certeyn, olde dotard, by your leave

You shall have queynte right enough at eve …

What aileth you to grouche thus and groan?

Is it for ye would have my queynte alone?

It was, in its time neither rude nor pejorative, but merely descriptive of the female genitalia. It has taken time, the prudish values of the Puritans and Victorians, to transform it to the most taboo word in the English language.

Its first written appearance in Middle English, where it has taken on what might be considered more than the mere anatomical can be found in a manuscript that predates 1325, The Proverbs of Hendyng, which advises women,

Ȝeue þi cunte to cunnig and craue affetir wedding.

Give your cunt wisely and make demands after the wedding.

A statement about expediency and advantage in deed, more pithy than Cicero, and as succinct as our political correspondent. Perhaps, just perhaps, our anonymous monk was not commenting on the head of his Abbey at all, perhaps he was as prescient, but not quite as poetic, as his contemporary Nostradamus. Perhaps he had a vision of a leader in an undiscovered country, a distant land, a leader given to political expediency, a student of Cicero, espousing quaint values and perfectly willing to measure personal advantage against morals derived from the authority of a manipulated demos. Maybe that’s why he drew a hole, and a stupid looking ear, and wrote, “fuckin Abbot”.