In pagan times a river was seen as the crossroads between worlds, the life giving property of water, the power of flood, the mystery in reflection. It is no wonder than that rivers and lakes became sites of offering, where people would throw offerings, items of symbolic value, sometimes mere totems and trinkets, baubles, coins or household items, other times, perhaps in measure to the import of their prayers to what ever mysterious power they beseeched, items of great significance, of great value, tools of trade, treasure and weapons, to disappear beneath the waters and enter, that other realm.

Thus we have to this day the sometimes tawdry tradition of the wishing well, plastic pastiches of which appear in shopping malls and parks, and the romantic superstition of throwing coins in a fountain, from the merest pool to great monuments in marble, both appeals to a mystery and with curiously equal weight to alter fate. We also have legends, like Excalibur, the steel forged sword, both symbol and tool of worldly power, risen from stone and fire, and returned, vanished, perhaps quenched and lost, perhaps merely held in keeping in that other realm beyond the surface.

Such river sites have proven also a crossroads of time, preserving in mud and silt in the depths all manner of treasures and trinkets, all with a valuable tale to tell. One of the most remarkable and mysterious pieces to have been brought back is a medieval sword, found in the river Withan, near Lincolnshire.

The Withan Sword was found in 1825, and was presented to the Royal Archaeological Institute. Recently on display as part of the British Library’s Magna Carta: Law, Liberty and Legacy Exhibition, Julian Harrison of The British Museum asked on the Museum’s blog for help in deciphering the mystery of the sword. A steel sword very typical of the high quality kind used by the great knights and nobles of the 12th and 13th century, at the time of Magna Carta and Richard the Lionheart’s Third Crusade, bearing a cruciform hilt, and a long, double edged blade. All features of the kind of sword used by the Christian knights of England, France and Germany, the centre of swordsmithing at the time. At almost a metre long, 16cm across the hilt, weighing a kilo and a quarter, such a weapon wielded by practiced warrior could, to use the traditional parlance, easily cleave a man’s head in twain.

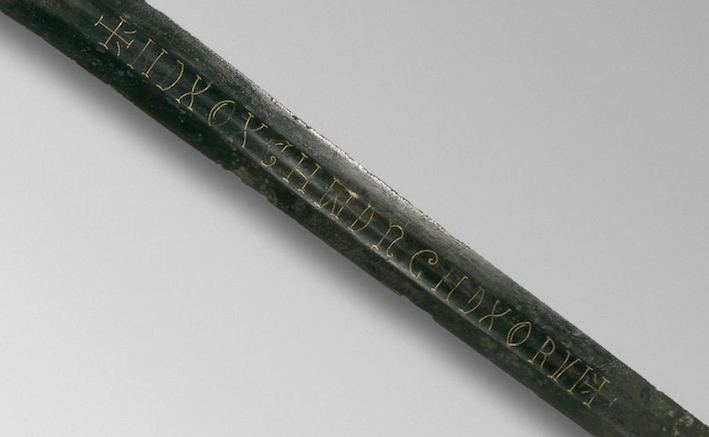

Yet the Withan Sword also has a round pommel, it is fullered – cut with parallel grooves that run the length of the blade on either side, (not to allow blood to flow off the blade, as is often assumed, but rather a technique that lightens the blade without sacrificing strength) and an inscription in a language that appears to be a hybrid of English letters and Norse runes, between crosses, which reads +NDXOXCHWDRGHDXORVI+, all features usually found on Viking swords.

The age of the Vikings had ended some 200 hundred years earlier. Was the sword the last possession of an aged Norse warrior, a remnant of the Dark Ages, holding on to traditions at the crossroads of history, unifying two traditions in this magical blade?

Actually, the mystery is entirely more prosaic. Marc van Hasselt of Utrecht University’s Hastatus Heritage Consultancy replied to The British Museum’s call for an answer to the mystery.

“Inscribed swords were all the rage in Europe around the year 1200. Dozens of them have been found, from England to Poland, from Sweden to France. While researching a specific sword-blade found in Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands, I found around a dozen other swords which had striking similarities. One of those swords was the River Witham sword, making it part of a large international family. Using the excellent research by Thomas Wagner and John Worley, an image of a hugely successful medieval workshop was created, making ‘magical’ swords for the elite.”

Van Hasselt goes on to describe how the runic looking letters made in gilt wire on the blade are actually merely stylized Latin. Latin was the lingua Franca of the medieval world, the language of travel, trade, scholarship, and religion. The inscriptions are not an unknown runic and English dialect, rather they represent religious mottoes and invocations in Latin.

“Let’s compare the River Witham sword to the sword from Alphen: both start with some sort of invocation. On the River Witham sword, it is NDXOX, possibly standing for Nostrum Dominus (our Lord) or Nomine Domini (name of the Lord) followed by XOX. On the sword from Alphen, the starting letters read BENEDOXO. Quite likely, this reads as Benedicat (A blessing), followed by OXO. Perhaps these letter combinations – XOX and OXO – refer to the Holy Trinity. On the sword from Alphen, one letter combination is then repeated three times: MTINIUSCS, which I interpret as Martinius Sanctus – Saint Martin. Perhaps a saint is being invoked on the River Witham sword as well? ”

Think then of the Withan Sword and its brethren, originating in an elite workshop using the latest techniques and equipment in Germany, not as something magical and mysterious, but perhaps more like the latest BMW, with all the optional extras. Viking style pommel – for superior balance, fullered blade, a hi-tech technique creating lightness, maneuverability, strength, and the gold inscription? A custom finish, a touch of bling, appealing to individuality as much as to a higher power.

There had been stories and myths of magical swords in the Norse tradition, in Irish folklore, in Saxon legends as well as English. The wonder of the Withan Sword is that in its appeal to that tradition, it shares both the physical power of a well crafted weapon, the symbolic power of the status symbol, but also something of the theatricality of the shopping mall wishing well.

The exact meaning of the inscription may never be known, but it hardly matters, however one important mystery remains. While it is possible such an expensive and treasured was lost by mischance, the Withan River has proved to be one of those places between worlds where people from thousands of years ago have cast in treasures and totems, in an appeal, an offering, to that other world. The mystery is, that that tradition from many thousands of years ago, from the neolithic, the bronze age, the iron age and into the age of steel, still holds sway.