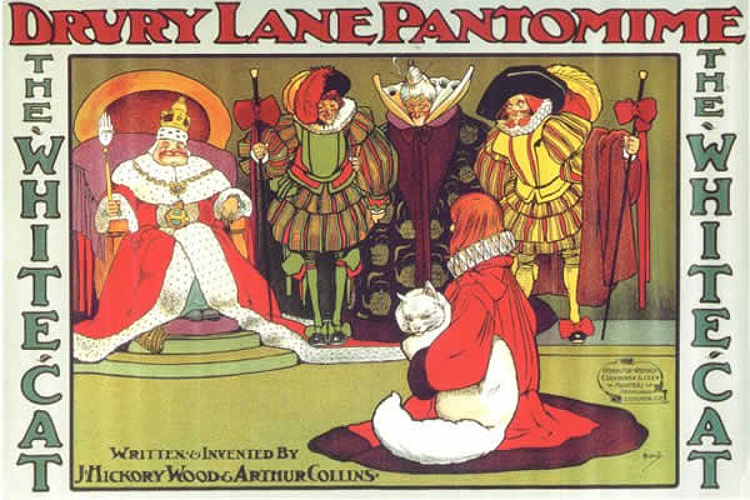

The Christmas panto is a very British tradition, one still embraced in some former colonial states and eschewed altogether in others. For those of you who are unfamiliar with the panto (cough *Americans* cough), it is a very silly play filled with campy stock characters, puns, and lowbrow humour. Some of the characters include a Principle Boy played by an actress wearing the shortest costume possible, a Panto Dame played by a man in the worst drag imaginable, and a Baddie so simultaneously inept and over the top that it staggers the imagination. The panto also relies heavily on audience participation, For example, if the Baddie is sneaking up on the hero of the play, the audience should shout out, “S/He is behind you!” Moreover, at least one of the characters frequently addresses the viewers and engages them with the activities on stage.

The idea that there should be a panto to make the Yuletide a happy one was firmly ensconced in the English cultural expectations by the end of the Regency period (circa 1795 to 1837), thanks to a man named David Garrick. Garrick was an 18th century actor and theatre promoter who wanted to capitalize on the popularity of the Italian commedia dell’arte performances, plays with stock characters and ribald jokes appealing to the most common denominator of the audience, that were a raging success across continental Europe. However, Garrick wanted to cash in on the craze without compromising the dignity of the Shakespearean stage with such fluff. To avoid conflating real acting with the buffoonery of the panto, Garrick modelled the concept that the panto was a special Christmas treat outside of the actual work of the theatre.

Christmas pantos were, of course, a huge hit. By the time Jane Austen’s works were being published, the panto was a Christmas “tradition” as deeply embedded in the English psyche as decorating with boughs of holly and eating gingerbread. Nowadays, the idea that there can be a proper English Christmas without the requisite local panto being produced is very nearly sacrilege. Might as well leave out the Nativity!

Although the holiday panto really only dates back to the Regency, the reasons Garrick chose Christmastime – rather than Easter or Midsummer – for the seasonal performance has roots that go back much, much farther into British history. It can be traced to the Tudors and beyond, all the way back to the Roman invasion and the pre-Christian era.

Prior to the Romans coming ashore to pester the Britons, the inhabitants of Great Britain celebrated a religious festival at midwinter involving (as it so happens) mistletoe, holly, and feasting. The Romans added their own spin on things by introducing the festive notions of Saturnalia to the midwinter celebrations, with drunken parties and a Lord of Misrule directing topsy-turvy social constructions wherein the servants were waited on by the masters, as well as various comedic productions. As the British picked up Roman habits, and Christianity became a global religion, the commemoration of Christ’s birth was grafted on to the older ways of marking the winter solstice. Not only did the English retain their mistletoe and feasting, they added the Roman traditions of gifts, debauchery, and jovial pageants to the holiday.

By the Tudor time period (1485 to 1603), the Christmas festivities were not complete without the Lord of Misrule and a Feast of Fools. In the book Survey of London, written by John Stow at the end of the Tudor era, describes the function of the Lord of Misrule:

“[During] the feaste of Christmas, there was … a Lord of Misrule, or Maister of merry disports … in the house of euery noble man, of honor, or good worshippe, were he spirituall or temporall. Amongst the which the Mayor of London, and eyther of the shiriffes had their seuerall Lordes of Misrule, euer contending without quarrell or offence, who should make the rarest pastimes to delight the Beholders. These Lordes beginning their rule on Alhollon Eue [Halloween, 31 October], continued the same till … Candlemas day [2 Feburary] … In all which space there were fine and subtle disguisinges, Maskes and Mummeries”

These masks and mummeries remained popular until the Puritans, who thought happiness was somehow demonic, outlawed Christmas and anything that might make the season merry and bright. Once Oliver Cromwell and his genocidal zealots passed away and the monarchy was restored (1660), Christmas came back with a roar. Nevertheless, a great many Christmas pastimes had to be rebuilt from spotty memories or from scratch. What was certain, in the mind of the populace, was that Christmas was supposed to be a time for fun as well as rejoicing.

The next few decades of British history was full of revolutions and uncertainty, so much so that the Lord of Misrule might have been made superfluous by the rampant misrule occurring throughout the kingdom. At any rate, by the time David Garrick came along in the Georgian era (which started in 1714 and ended when Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1830) there was a need for more frivolity at Christmas. The panto, with its ridiculous stylings and its overthrow of propriety and gender roles, was the perfect thing to echo the joyousness (real or imagined) of the Christmas in ye olden days. Even Queen Victoria, so seldom amused by anything and expressing little enjoyment of anything other than her husband in bed, liked a good panto at Christmas.

Although with pantos, you tend to like the ‘bad’ ones better!

Kyra Cornelius Kramer is an author and researcher with undergraduate degrees in both biology and anthropology from the University of Kentucky, as well as a masters degree in medical anthropology from Southern Methodist University. Her work is published in several peer-reviewed journals, including The Historical Journal, Studies in Gothic Fiction, and Journal of Popular Romance Studies. She is also a regular contributor to Tudor Life Magazine, the magazine of the Tudor Society. Her books include Blood Will Tell: A medical explanation for the tyranny of Henry VIII, and The Jezebel Effect: Why the slut shaming of famous queens still matters.

Kyra Cornelius Kramer is an author and researcher with undergraduate degrees in both biology and anthropology from the University of Kentucky, as well as a masters degree in medical anthropology from Southern Methodist University. Her work is published in several peer-reviewed journals, including The Historical Journal, Studies in Gothic Fiction, and Journal of Popular Romance Studies. She is also a regular contributor to Tudor Life Magazine, the magazine of the Tudor Society. Her books include Blood Will Tell: A medical explanation for the tyranny of Henry VIII, and The Jezebel Effect: Why the slut shaming of famous queens still matters.

Follow Kyra on her website, Facebook and Twitter