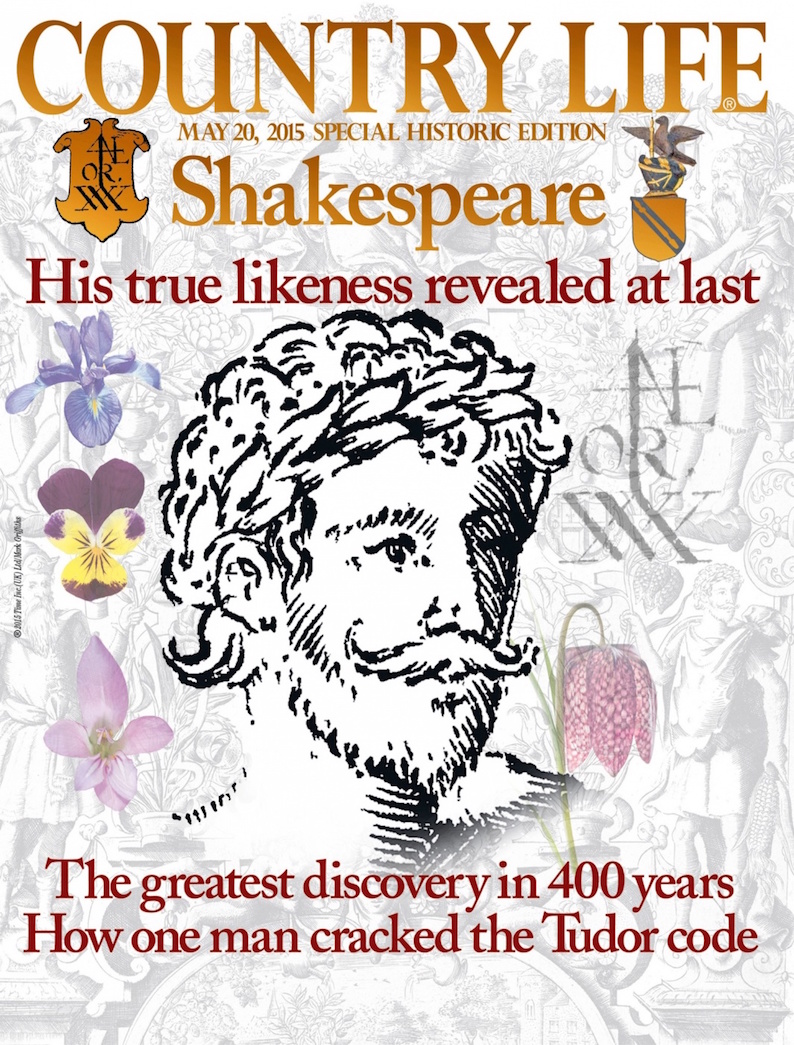

Historian and botanist Mark Griffiths in a recent article in Country Life Magazine claimed to have discovered the only verifiable portrait of Shakespeare made during the bard’s lifetime. The editor of Country Life, Mark Hedges, trumpeted it as the “literary discovery of the century.” He went on to say, “It is an absolutely extraordinary discovery; until today, no one knew what William Shakespeare looked like in his lifetime.”

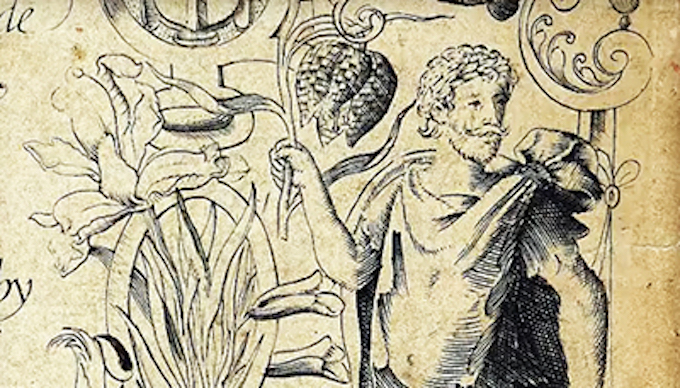

First things first, based on this illustration, we still don’t. A decoration, a cartoon does not qualify as a portrait. Regardless of how amusing, the figure depicted in Roman toga and wreath, despite a jaunty hipster moustache, is not even a sketch. It lacks both the detail and the purpose of a sketch or portrait, which is to depict an actual likeness of a person. We can perhaps call it an image. Whether it is an image of Shakespeare is a matter which the facts leave open to consideration.

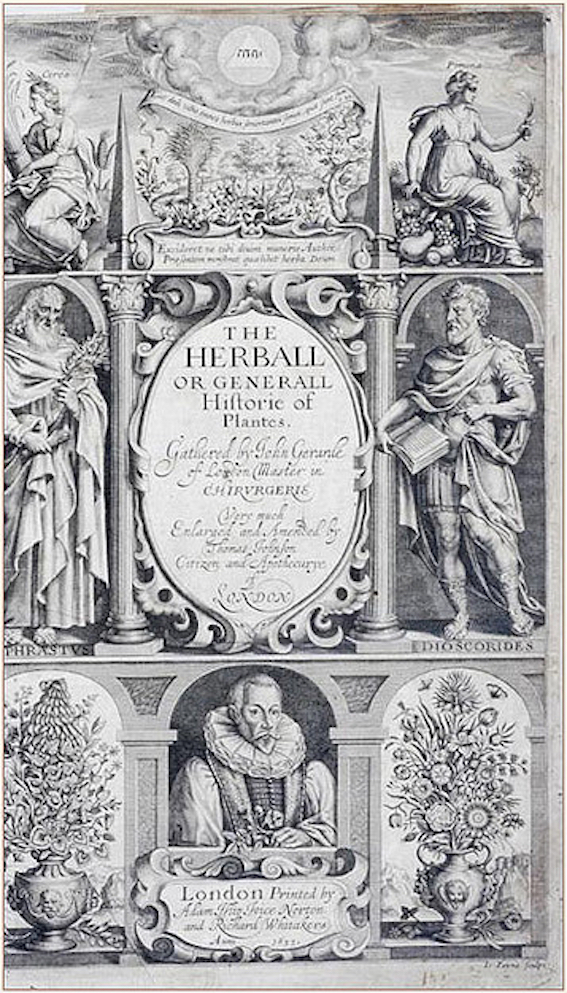

The image appears on the title page of the 1597 tome The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes, by John Gerard, published by John Norton. The most famous and popular herbal in the English language in the 17th century, Gerard’s work is predominantly a translation of the 1554 Dutch herbal by Rembert Dodoens (which also saw editions in Latin and French), with a few newly discovered botanical additions from the Americas and some English examples from Gerard’s own garden. The elaborate title page in which our purported Shakespeare appears is a copperplate engraving by William Rogers, the first and foremost proponent of the art in England in the 16th century.

The title page is an elaborate illustration, featuring four male figures surrounded and entwined with plants, flowers and symbolic devices. Illustrations of the Tudor period often included rebuses, puzzles that could be decoded.

Griffiths argument is at first compelling, the unraveling of the puzzle like something from The Da Vinci Code. Existing portraits meant he could easily identify three of the figures, John Gerard himself, Rembert Dodoens, the Dutch herbalist on which Gerard’s work was based, Lord Burghley, Queen Elizabeth’s chief minister and the patron of the work. Who was the fourth? In toga and laurel wreath, Griffith concluded the figure represented Apollo, Roman god of healing, knowledge and poetry. He set about decoding the other clues.

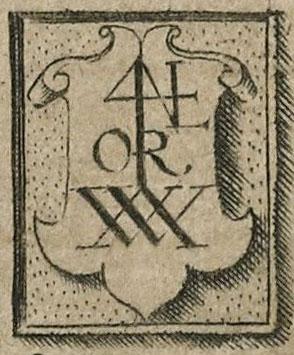

A figure 4, with an E joined to it, atop a spearhead dividing the letters OR, above overlayed letters, AW. Griffiths explanation, that the Latin for four, quater, commonly used as slang in Elizabethan times, with the addition of an E becomes quatere, infinitive of the Latin verb quatio, meaning to shake. OR is the heraldric term for gold, and Shakespeare’s family had recently been granted a coat-of-arms with a gold background. The AW? William?

The figure is holding a Snake’s Head Fritillary, an exotic plant from Turkey, (though probably brought over from France only 20 years previosuly) and all the rage in both fashionable and horticultural circles. In Venus And Adonis, portrayed in Shakespeare’s eponymous play of 1593, when Adonis is gored by a boar, Shakespeare has him transform not into the purple anemone of the classical myth, but into the chequered fritillary.

Sweetcorn the figure holds could refer to the corn Shakespeare mentions in Titus Andronicus, English and French irises to Henry VI.

While the devices, puzzles and obtuse references are exactly the kind of literary and artistic amusements enjoyed in the Tudor era, a stag couchant in water is Lyhart, an owl with the letters DOM on a wing is Oldham, Griffiths’ interpretation falls down on the briefest close examination.

Griffith argues that there is “only one piece of Elizabethan creative writing that refers to this extraordinary new flower and that is Venus and Adonis,” however to say that use of the flower then only references Shakespeare is poor logic. As devoted botanist Gerard undoubtedly cultivated the exotic marvel himself. In an age of high fashion a rare and beautiful curiosity would be included in the all important title decoration to pique and intrigue the wealthy purchasers for such a book.

Considering the sheer number of references to plants, flowers and herbs in Shakespeare, to then assume each future reference is also a connection to the bard is far fetched to say the least. In Ophelia’s speech alone, Hamlet, scene 5, we have rosemary, pansies, fennel and columbines, rue, daisy and violets. Does every subsequent image then mean Shakespeare? Of course not. Could very specific references, in context, mean Shakespeare? Possibly.

The lettered rebus itself that Griffiths claims means shake – spear also falls apart after a brief observation. Is it even a spear, with a figure 4 and an E? Ames Typographical Antiquities of 1749 states the cipher is the combined devices of William Norton and his nephew and apprentice, John Norton, the volume’s publishers. Combining letters in elaborate devices was a common practice of printers.

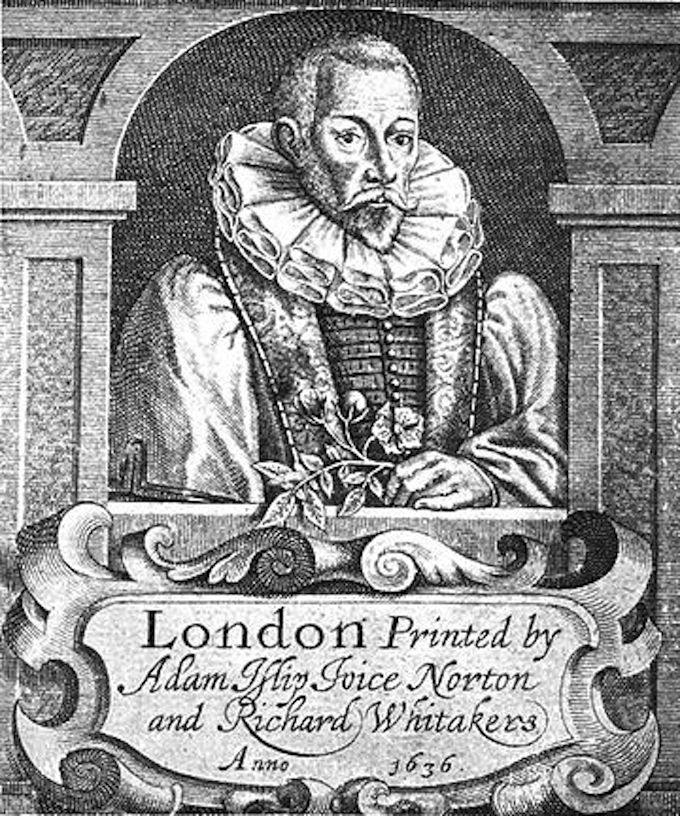

If not Shakespeare, who then is the fourth figure? Actually it is probably Gerard himself again, but in the form of Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek herbalist and physician from the 1st century AD who served in the Roman Legions, and whose De Materia Medica was the standard book of herbal knowledge for some 1500 years. How do we know this is Dioscorides? Not only is Dioscorides always depicted as a sandal wearing togaed hipster crowned with a laurel and sporting amusing facial hair, on the title page of the 1636 second edition of Gerard’s Herball, the more detailed but now not so mysterious figure is clearly labelled underneath as Dioscorides.

Could the figure be both Shakespeare, and Dioscorides? Well it’s possible, there are stranger things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in my philosophy, to paraphrase the poet. At the top of the second edition there is Pyramid and some Hebrew characters, so perhaps it is all a conspiracy of the Golden Templar Brotherhood, and the treasure, perhaps a lost folio, is hid under a stone that bears the image of St Vitus pierced with a pilum.

Why do I say could the figure is both Gerard and Dioscorides? The cartoonish figure in the first edition has perhaps a little twinkle in the eye, a wry turn of the lips, that is perhaps lost in the sterner Roman physician of the later engraving, but the portrait of Gerard also has something of that Bacchic twinkle. Compare the picture of the two, and consider, what better way to honour the creator of the new great herbal, but with the image of the creator of the old?