But it was as an aviator, or aviatrix as women pilots were known as back in the day, that Sophie was to become famous for, achieving world-wide renown for her flying achievements and, for a few years, becoming one of the most famous women both in Britain and the USA. Yet, by the time of her early death in 1939, she had faded into total obscurity. It is only recently that her remarkable life and achievements have deservedly been given due recognition.

When Sophie was an infant her father, John, known as “Jackie”, beat Sophie’s mother to death and, after a sensational headline-making trial, Jackie was imprisoned in a lunatic asylum for the criminally insane. Sophie overcame this trauma, spending her childhood at her grandfather’s house and various boarding schools, where she proved to be both a brilliant student and an accomplished sportswoman.

Whilst enrolled at Dublin’s College of Science, Sophie’s aunts helped arrange her marriage to British army captain William Davies Elliot-Lynn, who was some twenty years older than Sophie. The marriage proved to be disastrous from the outset, with Elliot-Lynn promptly returning to army life whilst Sophie, keen to do her bit, signed up as a dispatch rider for the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps.

After her demobilisation in 1919, Sophie returned to Dublin and resumed her scientific studies. She asked for a grant to enable her to complete her science degree, but it was turned down on the grounds that she was a married woman with a husband to keep her and therefore had no need or necessity for further skills. Sophie pressed on regardless, with typical determination, and duly succeeded in obtaining her degree.

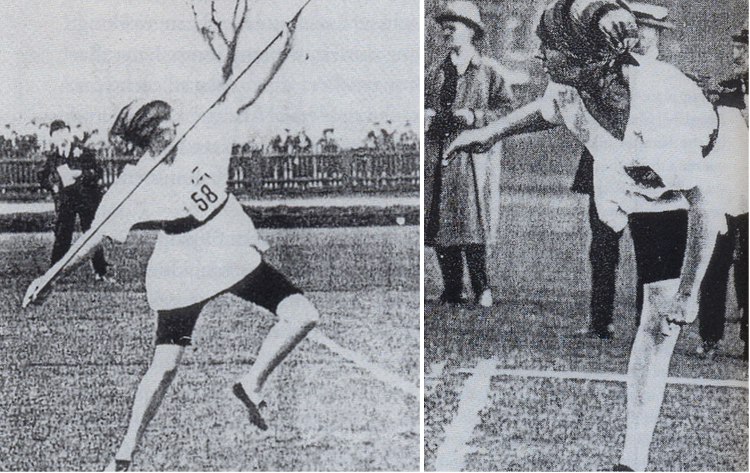

Sophie’s husband had headed for British East Africa after the war, where he had been awarded a farm under the Soldier Settlement Scheme. Sophie remained in Dublin to finish her studies and by this time was also becoming heavily involved in women’s athletics, becoming a founder member of the Women’s Amateur Athletics Association (WAAA). An accomplished athlete in her own right, Sophie developed a two handed technique for throwing the javelin and became Britain’s first woman’s champion in this discipline, but she was especially adept at the high jump where she set an unofficial world record.

Sophie followed her husband to East Africa in late 1922, but the marriage and the farm were both in irreversible decline by this this stage and she left soon after arriving, later claiming that her husband beat her on a regular basis. A formal divorce would follow in 1925, with her ex-husband dying two years later having been found drowned in the Thames.

Sophie, as vice-chair of the WAAA, campaigned vociferously for the inclusion of women’s athletics at the Olympic Games, with the prevailing view of authority at that time being that women’s athletics was unladylike and that they should only be allowed to compete in more genteel sports, such as archery.

In May 1925, Sophie flew to Prague to address a conference of the Olympic Congress. It was her first time ever in an aircraft and she became intoxicated with the whole concept of flight. By August, she had become one of the first members of the London Light Aeroplane Club, taking her first solo flight in October and obtaining a private pilot’s licence the following month.

Being a woman, Sophie found that her pilot’s licence did not afford her the same privileges as that of a man, despite demonstrating her abilities by attempting, and setting, numerous altitude records and being the first woman to take a parachute jump from a plane; landing in the middle of a football pitch whilst a match was taking place. Although she could compete in air races at frequently held air shows across the country – often beating the men – as a woman she was not allowed to take up passengers or otherwise earn a living from her skill. Women pilots were deemed to be inferior to their male counterparts purely on the basis of their gender, although some objected simply as a matter of course as they remained entrenched in outdated, misogynistic values; the predominantly official viewpoint being that women were naturally weaker than men and that this position would be compounded during a menstrual cycle, thus putting their passengers lives at risk.

Now she had the means to make a living from flying Sophie required her own aircraft and set about finding herself a husband who would finance her flying. Depending on one’s point of view, she perhaps cynically, or perhaps in a pragmatically practical way, made a list of the oldest and wealthiest bachelors in the British Empire, eventually selecting Sir James Heath, who was over forty years older than her. Polite society dubbed her a gold-digger, but despite being the subject of London society gossip the couple married in October 1927. The Avro Avian aeroplane that Sir James had bought for her was boxed up and sent by ship to be reassembled in South Africa, where they were on honeymoon and where Sophie – now known as Lady Mary Heath – planned to help promote aviation to local flying clubs.

Mary, ever the daredevil, decided that she would fly the tiny Avian back to London solo; a flight that no-one had yet made. She flew out of Cape Town in January 1928, although the flight proper didn’t begin until some three weeks later after various technical adjustments to her plane and the addition of an extra fuel tank. Now fully equipped for the arduous journey ahead, Mary flew out of Johannesburg airport and headed for London.

Heatstroke was her first problem, which she encountered over Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) forcing her to crash land. Although required to spend some time in a local nursing home to recover fully from the effects of the heatstroke, obtained in 100 degree heat, she was otherwise unharmed during the forced landing (although many newspapers had reported her killed in the crash) and, with the plane similarly miraculously undamaged, she simply got up from her bed and flew away. The rim of the Rift Valley, west of Nairobi, presented the next obstacle to Mary as her small Avian struggled to obtain the 9,000 feet altitude needed to clear this remarkable natural feature, which is one of the few wonders visible from space. Throwing out all unnecessary weight from her cockpit – which included books, spare pairs of shoes and, somewhat bizarrely, tennis rackets – Mary managed to scrape over the ridge and continue on her way.

However, flying long hours in an open cockpit continually at the mercy of inclement weather was taking its toll, and Mary was forced to find unofficial landing areas on a frequent basis. In Sudan officials insisted on her having an escort as they were simply afraid of a woman flying on her own. This, of course, made no difference to Mary’s task of flying her tiny Avian and is just another example of the sexist attitudes that prevailed at the time. There were compensations, nonetheless, as much of the Africa that she flew over was, at that time, under British rule and during some of her stopovers she was often royally entertained; attending parties, playing tennis and even finding time to go on safari. However, not everybody was as welcoming, and Mary found herself being shot at by local tribesmen as she crossed Libya, with repairs to bullet holes in the fuselage being necessary when she was subsequently able to land safely. Terrified of having to put down in open water, she inflated bicycle inner tubes and put them around her neck prior to crossing the Mediterranean. Thankfully, they were not required, although they would have proved worthless in any event, as they soon burst when she gained altitude.

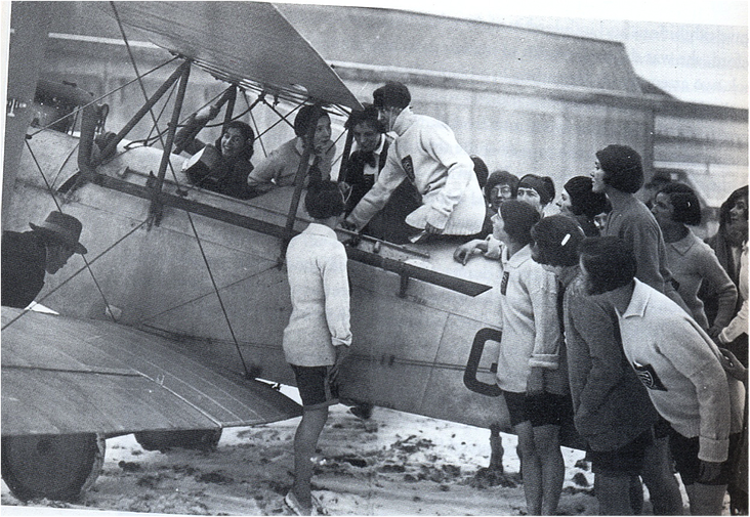

Finally, on the 17th May 1928, Mary’s small Avro Avian biplane made a bumpy landing at Croydon aerodrome – London’s main airport at the time – and, as it taxied across the grass airfield to the arrival area, it became engulfed by the vast waiting crowd of many thousands. Mary had flown her aircraft nearly 10,000 miles from Cape Town, maintaining the aircraft herself and becoming the first person to make a such a flight. The spectators were used to seeing pilots descend from their aircraft after landing wearing oil splattered overalls and goggles; Mary looked more like a fashion model as she stepped from her plane in her midi-heeled shoes, silk stockings, pleated skirt, fur coat, pearls and cloche hat. In that moment she had become the most famous aviator in the world. Her husband, Sir James, was waiting for her, but they quickly became separated, not only on the day but in the weeks that followed.

Mary soon became estranged from her husband as she attended a seemingly endless whirlwind of parties and lectures throughout the UK, quickly followed by a tour of the USA where she would promote British made Cirrus engines. She was total box office, with thousands of people attending her lectures at various air clubs in the USA and she soon set up a second home there at a New York apartment overlooking Central Park. Home in England was, by this time, a house in Mayfair, where she entertained the likes of Lady Astor and became the darling of the London social scene.

Not content to rest on her laurels, within a matter of months Mary began competing in air races throughout America. The rewards were high, but so was the danger, with many pilots losing their lives as they dodged between pylons. Mary was competing in the National Air Races in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1929, when she clipped a chimney in struggling to avoid one such pylon. Her plane crashed straight through the factory roof, which the chimney towered over, down onto the floor below. The plane was destroyed and many thought that Mary must be dead as she was pulled unconscious from the wreckage.

Mary spent weeks in hospital in a coma and had a metal plate inserted into her skull, which had been fractured in the crash. Eventually, and somewhat miraculously, Mary recovered and left hospital only to be served with a divorce petition from her estranged husband, Sir James Heath, who was now also making public his refusal to pay any of the bills that Mary was running up, most notably with expensive fashion house dressmakers. Sir James had finally had enough of being little more than a bank, funding a wife whom he never saw and thus effectively enabling her to treat him as a cuckold, not with another man, but to fame, public adoration and above all, flying. The very public manner of the divorce probably did a gentleman like Sir James no credit, but his ire is undoubtedly understandable, even though it must surely have crossed his mind before the marriage that he had two very attractive qualities; his money and a title.

A month after Mary’s epic flight from South Africa another aviatrix was pushed to the forefront of the public’s attention; a young American woman by the name of Amelia Earhart. Her publicity was managed by the controversial figure of George Putnam, the man responsible for marketing the name of Charles Lindberg; who was the first person to make a solo, non-stop flight from New York to Paris. After the flight Putnam effectively hid Lindberg away and instructed him to write a book about his momentous achievement; the book was a huge success and made Putnam a fortune. He realised that the next big thing would be for a woman to fly the Atlantic and had arranged for the American ambassador’s wife, Amy Guest, to be a passenger on a flight that would be flown by someone else, but which would still be a flight that could enable Putnam to announce her as the first woman to “fly” the Atlantic. However, Guest’s husband blocked the notion and it was purely by chance that Putnam came across Amelia Earhart, who, being physically similar to Lindberg, was thought to be an ideal replacement. Earhart was less complicated in character than Mary Heath and, by very many accounts, a far nicer person, feeling only admiration, rather than rivalry, with Mary’s achievements, even to the extent of later being invited by Mary to take a flight in her record breaking aircraft. Amelia was so impressed with the Avian that she bought the aeroplane from Lady Heath and had it boxed up and shipped back to America. They could, undoubtedly, have become friends, but Amelia found herself placed in a very difficult position by Putnam and his ruthlessly efficient publicity machine and so, one month on from Mary’s landing, Amelia Earhart was bundled into the back of a plane, complete with a pilot and a navigator, and duly became the first woman to “fly” the Atlantic.

Putnam’s publicity machine now pulled out all the stops, ensuring that Earhart’s name became first and foremost in the American public’s mind, advertising her as “the girl who had flown the Atlantic”. Putnam, a cold and ruthlessly efficient publicist, tried to ensure that nothing was going to stand in the way of Earhart being thought of as the female face of American aviation, least of all Lady Mary Heath. Even before her accident Putnam had instigated a bitter rivalry between Earhart and Heath, going out of his way to ensure that Amelia – aided by Putnam’s awesomely efficient publicity campaigns – completely eclipsed Lady Heath.

Putnam pressured the organisers of shows to exclude Mary and to put Amelia on instead, culminating in the total humiliation of Lady Heath when she turned up at one such event in America, thinking that she was to be placed on an inaugural flight for Cuba, only for Amelia to be placed into the cockpit instead. Amelia Earhart was without doubt a brave, independent, likeable and fair-minded woman, but undoubtedly succumbed, at least in part, to the cynically commercial demands of Putnam. After some six proposals of marriage from Putnam, the pair ultimately wed in February 1931.

Although ostensibly recovered from her crash, Mary still had to endure many months in and out of hospitals and clinics and her health would never be the same again. Unable to fly during this time of rehabilitation Mary still gave lectures and talks in America which, despite Putnam’s best efforts, still proved to be very popular, with her title and Irish background opening many doors. After getting her personal pilot’s licence back, but not her commercial licence – due to damaged sight caused by the accident – she began to fly again in 1931. At the same time she meet Jack Williams, a small man of Jamaican origins, but now residing in Kentucky, where he was employed as a jockey, and he duly became Mary’s third husband; although she chose to remain as Lady Mary Heath, realising that this would probably avail her of far more opportunities than the rather plain title of Mrs Williams could be expected to.

In 1932 – the year in which Earhart did fly the Atlantic – Lady Heath returned to Dublin with her new husband. Mary’s third marriage was now considered to be her most unforgivable faux pas and she was not only shunned by the superficial and racist elite of the London society set, but she also found herself cast as a commercial pariah as the advertising endorsements that she had once been showered with now abruptly stopped.

Despite this, Mary was happy in her marriage, and in 1934 took over the private aviation services at Kildonan aerodrome, just north of Dublin and set up her own aircraft company, Dublin Air Ferries Ltd. She also set up the Irish Junior Aviation Club where some of the original Aer Lingus personnel got their first taste of flying. But by this time aviation had moved into a different phase, with governments now setting up state airlines able to offer commercial routes all over the world. The days of the pioneering maverick were over and Mary could no longer make a living out of flying, either as a pilot or as a business manager.

Partly due to these failings and, in all probability, still suffering with the long-term effects of her accident, Mary became so increasingly dependent on alcohol that – like many before her on her mother’s side of the family – she was classed as an alcoholic. Her marriage now failed due to her complete reliance on alcohol and her many appearances before the local court on drunk and disorderly charges became less newsworthy as these appearances became more frequent, becoming little more than sad readings in the small print of a dwindling list of papers that still thought her name worth reporting.

Mary was now an embarrassment, and the former darling of society was effectively abandoned to her fate by those that had previously fawned and clamoured for her attention. Mary would often disappear for months at a time on drinking binges and be found lying in the gutter of a street, where only the kindness of a passing stranger would prevent the possibility of an awful fate befalling her.

In May 1939, Lady Mary Heath suffered a fall from a tramcar in London. She was taken to St Leonard’s hospital in Shoreditch, London, where she died from head injuries without regaining consciousness. She was just 42 years of age and classed as having no fixed abode. A pathology report indicated that no alcohol was found to be in her system and that her fall, and her confused state of mind just prior to her collapse, were possibly caused by an old blood clot which was found to be in her brain.

Mary had outlived Amelia Earhart, who had disappeared and been declared dead during a flight over the pacific in 1937. Amy Johnson, another notable aviatrix of her day, who in 1930, had become the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia, was also to perish, less than two years after Mary (this January being the 75th anniversary of her death), when her aircraft crashed into the Thames Estuary, just off Herne Bay, Kent. Both of these remarkable and brave women are justly remembered and celebrated today, but Mary Heath’s achievements came before theirs and yet she remains entirely forgotten. There are probably a number of reasons for this, first and foremost is that Amelia and Amy died doing something that the public recognised them for, namely flying, whilst Mary’s name had long since disappeared from the public’s consciousness. But sexism and racism also played an irresistible part in Mary’s downfall, added to by her very human failings, which meant that the woman who had overcome so much to get where she did, ultimately succumbed to a tragic fall from grace and an untimely, premature death – Lady Icarus had indeed fallen back to earth after her short, but glorious, days in the sunshine.

In the golden age of pioneer flying many women whom we remember today lost their lives; they accepted the risks and the price they had to pay for their obsession. Most of them never had families, never had children and died at a tragically young age; it cost them everything and the risks and deprivations seemed to be accepted and understood by them all.

Lady Mary Heath was accused of being a gold-digger and of being obsessively, perhaps even deviously, selfish and single-minded in trying to achieve her aims and further her own ambitions and self-worth. But Mary had overcome many hurdles, not least that of her birth at a time when snobbish and prejudiced English society regarded their hick Irish cousins from across the water as persons who could at best be tolerated, but who could never be regarded as their social equals.

Mary Heath’s pioneering flying achievements, as well as her efforts in helping to establish a greater and fairer role for women’s athletics, should mean that this undoubtedly brave, determined and resourceful woman should be justly remembered and praised alongside all the other great names that we remember today from those terrifying, but thrilling, days of pioneering aviation.

In 2013, pilot Tracey Curtis-Taylor, inspired by a recent biography of Lady Heath – Lady Icarus: The Life of Irish Aviator Lady Mary Heath – written by the journalist Lindie Naughton, recreated Lady Heath’s remarkable and historic 1928 journey. Flying in a restored Boeing Spearman biplane, Tracey completed the journey in six weeks and found the experience to still be extremely arduous and difficult 85 years on from Lady Heath. A documentary – The Lady Who Flew Africa: The Aviatrix – which covered Tracey’s amazing journey and which also shed some light on the unjustly forgotten Mary Heath, was aired on the BBC in March 2015.

Besides a small plaque on the house where she lived as a child, there is no public recognition of Lady Heath in Britain and Ireland. Her book, Woman and flying (1929), is hidden away on a lower shelf of the British Aerospace Library, and Lindie Naughton hopes that a re-release of her biography will attract a wider audience this time around. It certainly deserves to.

Sources and further reading:

Naughton, Lindie, Lady Icarus: The Life of Irish Aviator Lady Mary Heath (2004)

Rice, Dennis, The Incredible and Utterly Tragic Story of “Lady Icarus” (2015)