Hester was born in 1776, an age of revolution, to an eccentric father whose main passions were science and inventions, resulting in him spending more time in his own laboratory than he ever spent with his children. Upon the advent of the French Revolution he channelled all of his energies into sympathising with the revolutionary cause, even to the extent of calling himself “Citizen Stanhope” and referring to the family estate at Chevening, Kent, as “Democracy Hall”. Hester was the only one of the Earl’s six children to stand up to him, attending a party without either permission or a chaperone – a shocking thing to do in 18th century England – and hatching a plan with her uncle to spirit her brother to the continent in order for him to attend university, her father having forbidden any of his children access to schooling outside of private tuition at Chevening. Hester’s father disowned her for such defiance and, being effectively homeless, she was forced to move in with her maternal grandmother. Strong-willed and independent, she travelled abroad for the first time in 1802, travelling on the continent on the Grand Tour and only returning to England when war broke out again between Britain and France.

Upon the death of her grandmother Hester was homeless again until an invitation came from her uncle, William Pitt the younger, to come and live with him at Walmer Castle, a home he now enjoyed as the current Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. Whilst there, Hester was responsible for the new landscaping to the rear of the castle, which later evolved into the magnificent gardens that currently exist there. When Pitt was returned to the premiership of the country in 1804 Hester moved with him into 10 Downing Street and, as Pitt remained a bachelor, took on the role of hostess, entertaining and socialising with the very elite of British and foreign society.

Hester had many male admirers, although many thought her to be too independent and outspoken to be safely regarded as marriage material. One such man, Granville Leveson-Gower, was probably more attracted to her connection to Pitt than in having any genuine feelings for Hester and she was indeed only one of many women that he frequently entertained. However Hester had fallen for him completely and was devastated when he ended the relationship, with much unkind society gossip accentuating her pain. Shortly afterwards, in 1806, Pitt died from ill-health and the government gave Hester one week’s notice to remove all of her possessions from Downing Street.

Thanks to a request from Pitt, made shortly before his death, the British government awarded Hester an annual pension for life of £1,200 pounds a year, a very tidy sum for that time. With many of her so-called friends abandoning her after Pitt’s death and the latest love of her life, General Sir John Moore, meeting his death in Spain in 1808, during the Napoleonic Wars (one of her brothers also died in the same campaign), Hester took the spontaneous decision to leave England and travel to the East. She advertised for a personal physician to accompany her on her travels and also insisted that her maid, Elizabeth Williams, join her on what she presumably thought would be a voyage of discovery on many levels. Charles Meryon applied for the position of medical travelling companion, passed muster at his interview with Hester, and duly left England with her in 1810. Hester had no idea at this point as to precisely where she would go, but would first head for Gibraltar, then Malta and on eastwards.

Whilst in Gibraltar Hester added a young Englishman named Michael Bruce to her travelling party. Bruce, although many years her junior, became Hester’s lover and she somewhat scandalised the close-knit society of this outpost of British Empire by openly flaunting this fact at every available opportunity, much to the chagrin of Dr. Meryon, who was himself hopelessly smitten with Hester.

By the time Hester’s expedition reached Corinth, Greece, its personnel had swollen to nine people and it was claimed that, upon reaching Athens, Lord Byron dived into the sea to greet her. He was, however, seemingly more scornful of her than an admirer, describing her as “that dangerous thing, a female wit”. Nevertheless, it was reported in the press that, after leaving England in 1816, it was Lord Byron’s intention to join Lady Hester’s expedition at some point, although that idea seemed a fanciful notion and never materialised. Hester now had the somewhat hair-brained idea that, after pushing on to Constantinople, she would win the goodwill of the French Ambassador there, obtain a passport to France, travel to France, ingratiate herself into the confidence of the Emperor Napoleon and then return to England where the information she had accumulated could be used to help in his overthrow. Unsurprisingly, and perhaps mercifully, her attempt to become a spy was thwarted by cautious diplomats and a passport was never issued. Whilst in the Ottoman capital Hester often joined the crowds at public beheadings – a popular entertainment of the day – on one occasion being presented with a severed head on a silver plate. This gruesome gift left her unruffled, but rather saddened that it was being passed around “like a pineapple.”

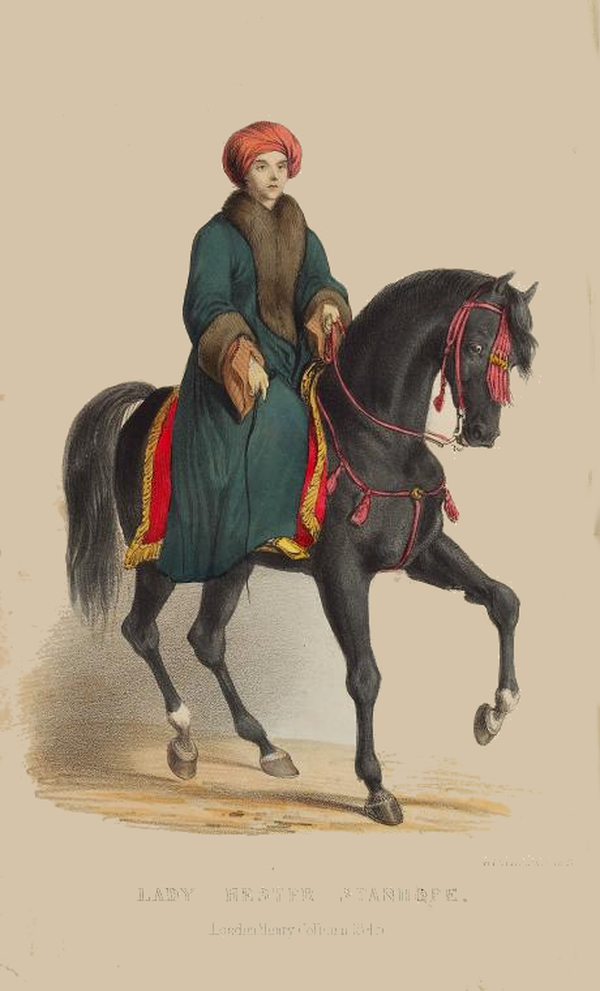

Heading ever eastwards, the party headed for Cairo, Egypt, but were shipwrecked on route. All luggage was lost and her Ladyship replaced her stiff English dresses with the attire of the region and became clothed in men’s boots, baggy trousers, waistcoat, turban and sword. From that day on she dressed as a man, although what she earnestly believed was typically oriental attire was actually closer to Regent Street Tunisian and, according to Dr. Meryon, she was often mistaken for a young Turkish bey “with his moustachios not yet grown.”

After reaching Cairo she set up temporary residence before paying a call on Muhammed Ali, ruler of Egypt, as a courtesy (as she saw it) between equals. The humidity of the Nile Delta, along with the flies and fleas of her temporary home, precipitated a further ride eastwards, and in so doing she became one of the first Europeans (often the very first) to travel in the deserts of Syria and the Lebanon.

Arriving in Jaffa, she at once set to the task of obtaining a safe conduct across the bandit-infested countryside to Jerusalem. With astonishing courage she rode directly into the bandit-in-chief’s camp and with a combination of guts, guile and bribery secured the word of the bandit’s leader, Shaikh Abu Ghosh, head of the Abu Ghosh clan, that her party would be unmolested. He kept his word and Lady Hester duly made her own grand tour of the Holy City, before proceeding on to Nazareth, Acre and many other cities that were but Biblical words to nearly all westerners at this time.

Lady Hester was fast becoming dangerously intoxicated with the welcomes she now received everywhere she went. Wearing her own form of male clothing and sitting astride an Arab stallion, the sight of a tall, pale-skinned English lady in pantaloons and turban riding at the head of a caravan of camels was certainly a unique sight to the local population. Some thought her to be a princess, others a prince and many more regarded her as “neither man nor woman, but a being apart.” A seemingly never-ending stream of fearsome blood-thirsty sheiks and brigands now sought an audience with this mysterious, almost mythical woman, who seemingly knew no fear and as such had earned their total respect. One whom she would later enchant, Emir Bashir, would later distinguish himself by castrating a rebel leader’s three sons, before burning out their eyes and cutting away their tongues. Tolerance, diplomacy and moderation were not bywords to be associated with this man, and to be dictated to by a woman would have been unthinkable, and yet Hester faced him, as she faced all of the men she met, with a combination of fearless charm and belligerence. She impressed them all with her honest straight-talking, her courage and her horsemanship. She shaved her head, like a Muslim man, in order to make her turban fit more comfortably, started to smoke a traditional Nargile pipe and could now swear at her servants in three languages. Hester was starting to believe herself to be some form of divine power to the people she now met, declaring that: “All Syria is in astonishment at my courage and my success”.

She remained oblivious to the fact that the people she met accorded a generous reception to all guests and travellers as an article of faith and so, to Lady Hester, these actions merely convinced her that here, at last, she had discovered a race of men which truly appreciated her aristocratic bearing, lineage and inherent superiority, which the English had recognised so fleetingly during her uncle’s days of power. Lady Hester had confused hospitality with awe and servility, toleration with submission, and acclaim with admiration. It was a mistake that she never recognised, even until her dying day and one that would later be repeated by many others who failed to truly understand the diverse cultural differences that existed between East and West.

Lady Hester now conceived the idea of visiting Damascus, a city then implacably hostile to outsiders, particularly Europeans and women. Making her usual frontal assault on her objective, she asked for, and received, an invitation from the Pasha of Damascus himself and then entered the city on horseback unveiled. This violated two laws as Christians were forbidden to ride a horse within the city walls and women had to cover their faces in public. Hester’s appearance was at first greeted with a stunned silence as people gawked in disbelief, but then, bizarrely, they started to cheer, spreading coffee around her horse in a gesture of respect. The bazaar rose as she passed by and rumours soon spread that this strange white female was a divinity who chose to be English royalty in her earthly form. Lady Hester, perhaps wisely, did nothing to discourage such illusions and confidently acted in the manner that she assumed a Goddess would and as such no door remained closed to her.

One accessible “forbidden city” remained. Palmyra, the seat of Queen Zenobia’s ancient desert kingdom east of Damascus that had once defied Rome. The ruling tribesman of the area barring her way this time was the Bedouin Emir of the Anazah. Typically, she demanded to be invited to meet with him and her demand was, of course, successful. She went alone to see him (save for two guides) despite dire warnings that the Emir was a bloodthirsty despot who would sooner stake her out in the sun than talk to this strange English woman. Standing before him she said: “I know you are a robber and that I am now in your power, but I fear you not. I have left behind all those who were offered to me as a safeguard…to show you that it is you whom I have chosen as such.”

The Emir was captivated by her courage and charm and not only granted safe passage to her and her travelling companions, but also provided a guard of seventy Bedouin lancers to ensure her personal safety.

In March, 1813, she arrived at Palmyra; “a forest of mutilated columns carelessly scattered on the tawny plain.” To the throbbing of desert drums she led a procession of Bedouin notables, followed by lesser tribesman, down one of the few well-preserved colonnaded Roman avenues leading to the great temple which stood at the centre of the city. Beside each column was stationed a young maiden and, as the procession passed, each fell in beside the mounted Lady Hester as escort, all the way to the temple, where, she remembered much later, when time and memory had perhaps embroidered the truth: “I have been crowned Queen of the Desert, under the triumphal arch at Palmyra. I have nothing to fear…I am the sun, the stars, the pearl, the lion, the light from heaven.” In her own mind she had become the new Queen of Palmyra, the new Zenobia.

This was the to be the zenith of her previously aimless life and, little by little, the fall from this high-water mark began. Michael Bruce left for England, ostensibly to visit his ailing father. He promised to send Hester £1,000 a year to finance her desert adventures, but reneged on the promise and it soon became evident that he had succumbed to the rather more delicate charms on offer in London’s high society, scarcely even able to bring himself to write a letter. Plague ravaged the land and Hester nearly died from a fever which it is thought permanently damaged her brain and, perhaps because of this, the woman of action, bravery and adventure would slowly transform into a strange, reclusive hermit.

Now resident in a small convent called Mar Elias, in the foothills of Mount Lebanon, she began acting like a medieval monarch, feeding and clothing every beggar and outcast that came to her door. She showered vast sums of cash on any sheikh or prince who called on her to pay their respects, borrowing heavily to do so. Hester decided to mount an expedition in search of buried treasure in the city of Ascalon, after discovering clues in an ancient parchment, but no treasure was found and, instead of being the solution to her dire financial situation, the expedition merely increased her financial woes.

Despite her increasing eccentricities and her mounting debts the whole of the Middle East seemed to be falling under her spell. She had become that rare thing in a man’s world; a woman to be feared. Outraged that the Ansaries of Latakia had violated the laws of hospitality by murdering a French consul who had shown her much deference, she prevailed on a local chieftain to conduct a private war (probably financed by Hester) against the northern sect responsible. Fifty villages were burned and pillaged, resulting in the deaths of three hundred innocent men, with their women being dragged away in chains to be sold as slaves. A wild-eyed “Queen Hester” later rode triumphantly through the razed villages to inspect the carnage.

Lady Hester now became convinced that she would marry the Mahdi, an Islamic ruler that many Muslims predicted would appear in order to establish a reign of righteousness throughout the world.

When a foal with a twisted back was born at Mar Elias in 1817, Hester believed it fulfilled an old prophecy that this would be the horse to carry the Mahdi. The deformed animal was named Layla and kept plump and pampered in readiness for the big day. It was joined by a second mare, Lulu, which Hester intended to ride alongside the Mahdi and Hester ordered that the horses be fed sherbet and other delicacies as these were holy horses.

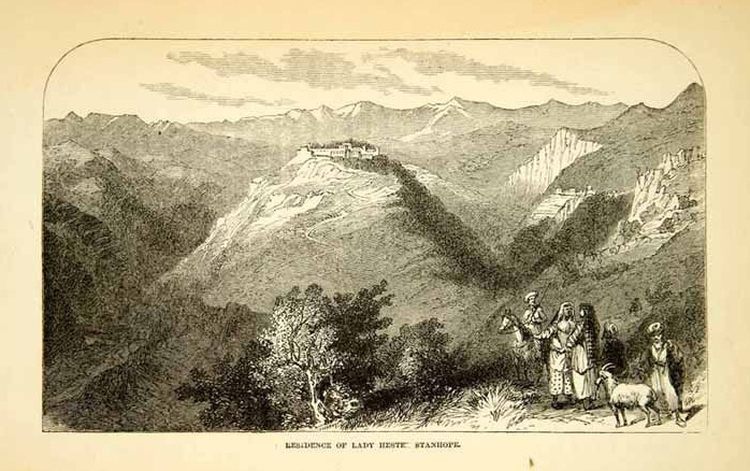

Hester left Mar Elias in 1821 and moved further up the mountains to a previously ruined monastery at Djoun (Joun), a strange hill-top fortress with twisting corridors, secret passages and scented gardens. Her only neighbours were the local peasants who looked on her as some kind of queen or prophetess.

When civil war broke out in the Lebanon in the mid 1820’s, desperate refugees poured up the mountain path seeking the protection of “Queen Hester”. Lady Hester never turned anybody away, she took them all in, feeding and clothing hundreds. This one woman relief effort bankrupted her and she borrowed yet more money, at enormous rates of interest. The warring factions, although somewhat irked at this safe-haven in the middle of their territories, never attacked Hester’s fortress, although they surely could have done. This was probably due to a combination of respect for Lady Hester and fear of the consequences of what might transpire if she was killed in such an action. As Lady Hester had openly declared her home and lands to be British, even the local tribesmen realised the implications of attacking an enclave under the protection of the British flag.

In 1825, Hester received the news that her second brother had killed himself in England. She had long felt unable to return, as word had spread about her indiscreet liaison with Michael Bruce, which, combined with her previously disastrous infatuation with Leveson-Gower, meant that, in Hester’s mind at least, she was now regarded as a fallen woman. She retreated into her mountain fortress and from that day on she was never to step outside of its gates again.

Her put upon, but loyal maid, Elizabeth Williams, died in 1828, and the ever faithful and devoted Charles Meryon, who had never been paid, reluctantly returned to England in 1831, where he married and started a family of his own. Despite this, he still harboured an unrequited love for Hester and, out of worry for her health and safety, he returned to visit her on two occasions before her death. On his last visit, in 1837, he was shocked by how far his old travelling companion had sunk. Her teeth were gone, her eyesight was going, her back was bent with her bones poking through paper-thin skin and she was coughing up blood. “Such dust!, such confusion!, such cobwebs!” wrote the doctor.

The English traveller Alexander Kinglake dropped by in 1835 and was struck by Hester’s enormous turban, skinny body and face “of the most astonishing whiteness”. Between sucks on her water-pipe she told him that she no longer read, “but trusted alone to the stars for her sublime knowledge.”

With her debts now totally out of control her once magnificent home began to crumble around her and, unable to pay her servants, they stole what they could at every given opportunity. The niece of Prime Minister Pitt the younger had become a national embarrassment to Britain and in 1838 the government cut off Hester’s “lifelong” pension in order to placate one of her exasperated Turkish moneylenders – although they failed to pay him anything. Now totally destitute, Hester wrote to Queen Victoria in protest and vowed to remain in her home “as if I were in a tomb, till my character has been done justice to.”

Hester lived out the remaining months of her life walled up inside her half-ruined fortress, alone, sick and surrounded by cats. There was no “justice” and no one came to help.

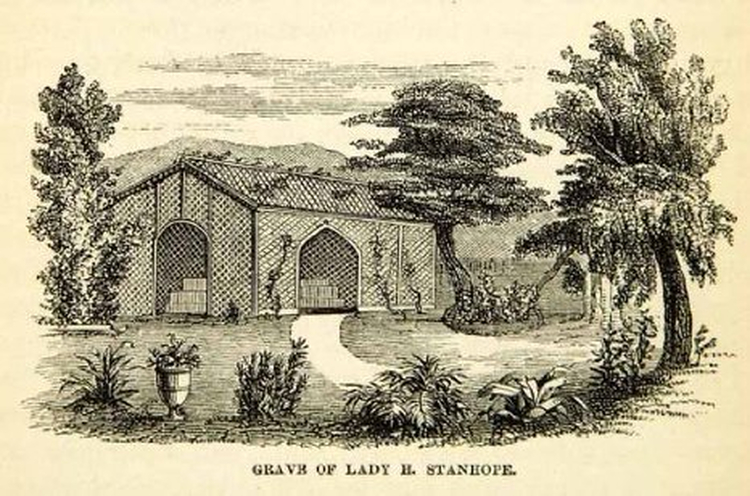

Death came in 1839, when she was 63, alone in an alien world, among alien people, whom she had tried for more than a quarter of a century to make believe were her own. A British official arrived at Djoun a few weeks later and found Hester’s body. It lay unattended and was starting to decompose.

Hester was buried in her garden at Djoun, until her tomb was destroyed during a civil war and she was then reburied in the garden of the British ambassador’s summer residence. She rested there in peace until 2004, when her ashes were scattered over the ruins of her former home. Lady Hester Stanhope would probably have been forgotten if it hadn’t been for the faithful Meryon, who wrote three volumes of memoirs about his travels with her, giving the world a picture of a truly remarkable woman. People may draw differing conclusions about her lifestyle, her morals, her treatment of people, the motives for her actions and even her sanity. What is unquestionable is her outstanding bravery that led a woman of English high society to choose the excitement of travel and adventure, leading her into the unknown and mysterious Middle East – a journey which is still a daunting prospect over 200 years on – rather than settling for a spinster’s life amongst the delicate, restricted and very dull conventions of the London social scene in Regency England.

Perhaps it will be fitting if the last words on this remarkable woman come from the lady herself, when she wrote: “…I have no reproaches to make of myself but that I went rather too far.”

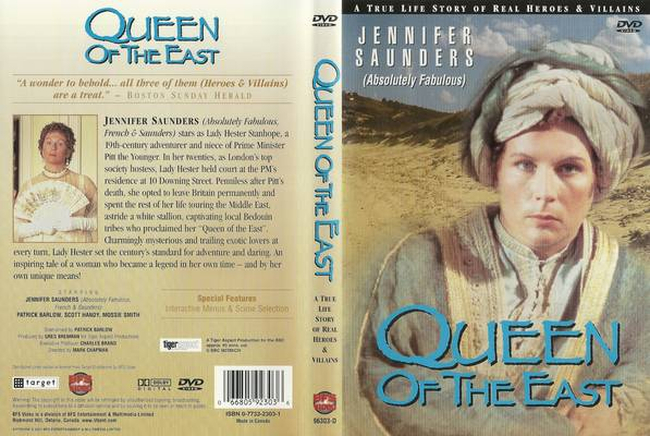

Lady Hester Stanhope as portrayed on film:

In January, 1995, the BBC aired the first in their series of Heroes and Villains entitled: Queen of the East. This was their interpretation of the life of Lady Hester Stanhope which, somewhat bizarrely, featured Jennifer Saunders as Hester in what was billed as her first “serious” acting role. Unfortunately, this proved to be the main weakness of the film, with many of her indignant outbursts resembling something out of a French and Saunders sketch. Purely in my opinion of course, this film contains very few insightful moments into the true Hester Stanhope and it is only at the end that Saunders’ character displays any real depth, with the poignant realisation that she would die friendless and alone in a foreign land.

Released on DVD some time ago, the full film (60 minutes duration) has recently been uploaded for viewing on YouTube. I first saw this twenty years ago when it originally aired and didn’t remember it being as bad as I thought it was when I saw it again recently. Surely, given the wealth of material to work with here, a fitting and worthy cinematic tribute to Lady Hester Stanhope cannot be too far away.

Bedlam Productions, the company behind The King’s Speech, is in pre-production on a film about Hester The Lady Who Went Too Far, a feature film based on a biography of Lady Hester written by Kirsten Ellis. Shooting will start next year and the title role has been offered to a “well-known” actress, but her name is being kept under wraps.

Sources and further reading:

Gibb, Lorna, Lady Hester: Queen of the East (2005)

Haslip, Joan, Lady Hester Stanhope: The Unconventional Life of the Queen of the Desert (1934)

Childs, Virginia, Lady Hester Stanhope: Queen of the Desert (1990)

Kinglake, Alexander, Eothen, or Traces of Travel Brought Home from the East (1844)

Russell, Mary, The Blessings of a Good Thick Skirt: Women Travellers and Their World (1986)

Robinson, Jane, Wayward Women: A Guide to Women Travellers (2002)

Ellis, Kirsten, Star of the Morning: The Extraordinary Life of Lady Hester Stanhope (2008)

Hodge, Jane, Passion and Principle: The Loves and Lives of Regency Women (1996)

Da Cruz, Daniel, “Queen of the Desert”: Lady Hester Stanhope (1970)

Mahon, Elizabeth, Lady Hester Stanhope, Queen of the Desert (2007)

Bendle, Simon, Lady Hester Stanhope: Kooky Desert Queen (2008)