The 2011 film of the Green Lantern was universally panned. A few die hard devotees were willing to forgive it its flaws. Even they were dubious. And yet there was one moment in which the whole cornball schemozzle was redeemed; when Ryan Reynold’s first cried out the catchphrase;

The 2011 film of the Green Lantern was universally panned. A few die hard devotees were willing to forgive it its flaws. Even they were dubious. And yet there was one moment in which the whole cornball schemozzle was redeemed; when Ryan Reynold’s first cried out the catchphrase;

In brightest day, in darkest night

No evil shall escape my sight!

Let those who worship evil’s might

Beware my power — Green Lantern’s light!

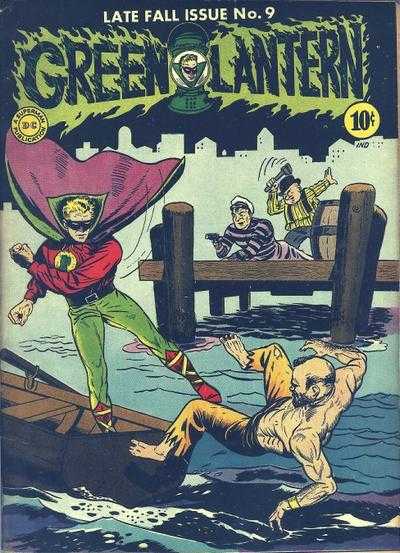

Even if you’re not the greatest fan, that was a moment which sent chills down the spines of the most jaded critic. The Green Lantern’s catchphrase as we know it first appeared in issue #9, 1943. There had been catchphrases before, they just did not ring true. Created by artist Martin Nodell and writer Bill Finger, The Green Lantern first appeared in All-American Comics #16, in 1940. Alan Scott, the first Green Lantern’s original oath was forthright, expressive without being vital;

…and I shall shed my light over dark evil.

For the dark things cannot stand the light,

The light of the Green Lantern!

SF legend Alfred Bester penned the story for issue #9, 1943, coining the catchphrase that has echoed down the ages, inspiring awe and wonder in legions of fans as villains cowered in fear. With that final cry of Green Lantern’s light! everyone new battle would be joined and villains would be vanquished. Not only vanquished, because the Green Lantern used wit, will and cleverness to defeat villains in clever ways. There was something dramatic, something epic, something Shakespearian about it. No surprise there, most of Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets were written in iambic pentameter. A meter of ten syllables with the accent on the second. The Green Lantern’s cry is similar, written in iambic tetrameter, lines of eight syllables long, with stresses falling on every second. It is a declaration that brooks no questioning, combining the catchiness of the iambic pattern, but with the shorter meter giving it more punch, more power than the Shakespeare’s more contemplative lyricism.

Bester went on to use similar powerful poetic phrases as crucial devices in his two legendary SF novels, The Demolished Man and Tiger! Tiger! Published as The Stars My Destination in the US, Tiger! Tiger! first appeared as a serialisation in Galaxy Magazine in 1956. The first hardcover edition was published by Sidgwick & Jackson in the UK in the same year. The title is of course from William Blake’s poem,

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

Which appears on the first page of the novel, and goes someway to describing villain, anti-hero, monster, brute Gully Foyle. Abandoned in space after an accident, almost rescued, abandoned again, the simple ship’s mechanic sets out on a quest for revenge, remaking himself in the process. It’s one of the true masterworks of SF, with tropes and devices that have become hallmarks of the genre; powerful and invasive governments, megacorporations, mutation and development of psychic powers, cybernetic enhancement of the body, all subjects that have been explored and expanded in sub genres as diverse as superheroes to cyberpunk.

Gully Foyle used poetry to remain sane in his desperate struggle to survive in the hostile environment of the remains of the wrecked space ship, it was also an insane expression of his pathological determination to get revenge;

Gully Foyle is my name

And Terra is my nation

Deep space is my dwelling place

And death’s my destination.

Later, the remade Gully, like the Count Of Monte Cristo, a changed man, remade as hero rather than merely revenger recites again;

Gully Foyle is my name

And Terra is my nation

Deep space is my dwelling place

The stars my destination.

Beyond his abandonment, beyond revenge, beyond even his new found wealth and fame, Gully Foyle’s destiny is humanity’s, finding spirituality in the mystery of the unknown, in exploration, discovery and wonder.

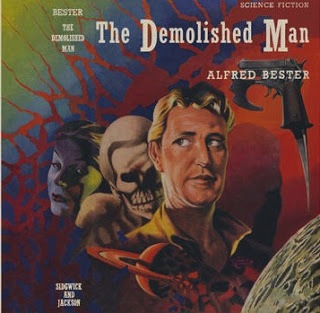

No less brilliant, but with a distinctively darker result, The Demolished Man, first published in 1952. The winner of the first Hugo Award, it follows a simple premise; in a world populated by mind-readers, telepaths, espers, how does one plan and commit murder?

Ben Reich, the protagonist (lets not call him hero), head of Monarch Utilities and Resources, is haunted by visions of a man with no face, persecuted and paranoid, he determines to take out the head of a rival family he blames for the bankruptcy of his family’s centuries old business cartel. Part of his plan involves mentally reciting,

Eight, sir; seven, sir;

Six, sir; five, sir;

Four, sir; three, sir;

Two, sir; one!

Tenser, said the Tensor.

Tenser, said the Tensor.

Tension, apprehension,

And dissension have begun.

a jingle especially designed to repeat and stick inside the head, an earworm, effectively blocking attempts by telepathic peepers to read his mind. What ensues is a tense and complex battle of wits and wills, ploy and counter ploy, as Reich attempts to cover up his crime and kill the only witness, while police prefect Lincoln Powell tries to get evidence against him. If the increasingly paranoid and unstable Reich fails he will suffer ‘demolition’ – his person stripped away in layers.

Again the poem is crucial to the story, no mere decoration, it not only encapsulates the conflict, it expresses something of the personality of the protagonist.

Again the poem is crucial to the story, no mere decoration, it not only encapsulates the conflict, it expresses something of the personality of the protagonist.

So with Green Lantern’s cry. It bears repeating.

In brightest day, in blackest night

No evil shall escape my sight!

Let those who worship evil’s might

Beware my power — Green Lantern’s light!

No mere catchphrase, the Lantern’s oath, his invocation as he powers Ring from Lantern was exactly that, a spell. The original Green Lantern’s ring and powers were magical. In 1959, after the comic had remained on the shelf for ten or so years, DC editor Julius Schwartz re-invented both the mythology and the character of the Green Lantern as the science fictional creation we know today. In Hal Jordan’s hands, the ring became a technological device. Although there are variations on the Lantern’s oath, and the universe and the character of the Green Lantern have gone through numerous transformations, the essential oath, the invocation, the simple call to light to battle evil, has remained the same. Undoubtedly it always will.

It may be a stretch to say Bester’s theme, of the poet – the intellect, the heart of reason, overcoming the brute, both within and without, is not as evident as it perhaps once was. In Green Lantern 2, if they can find some of that spirit, rather than the ‘jock out of water’ characterization they achieved in the previous film, the filmakers may redeem themselves.