The fable is at the heart of storytelling; it is a mystery, an exaggeration, a tall story, a romance, a story that takes us into the shadows, and out again, and teaches us more often than not a sharp, double-edged lesson. Studio Ghibli has taken the fable and elaborated, they have taught us a lesson that does not rap the knuckles or sting the heart, rather it swells it with possibility, through imagination, invokes wonder, through wonder creates joy.

A sense of wonder, the wisdom of innocence, a captivating aesthetic, a sense that what they are doing is both art and story is something largely lost from American animation. The most engaging recent piece, Up In The Air descended into sentiment, and what could have been an aesthetic exploration instead went for the CGI version of 1960s Rankin Bass “Animagic” puppet animation. Clunky if slightly humorous caricatures. As to the rest, big green oafs, braying donkeys, corny toys, braggart vehicles, and other wisecracking anthropomorphs are a weight on the imagination, a product more than an inspiration.

Studio Ghibli presents worlds where wonder has not been reduced to mere antics. Tales filled with mystery, charm, laughter, sadness, and adventure, and creates the extraordinary out of everyday magic. Innocence, naivette even, overcomes the challenges presented by life’s complex questions. These are fables, and a fable is of course a story of something fabulous that teaches and spellbinds both adult and child.

Here are five books we think share that genius, and would make great additions to Studio Ghibli’s body of work.

1.Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind In The Willows.

Most people are familiar with the classic tale of Ratty, Mole, Otter, Badger and the outrageous Mr Toad, first published in 1908, and their adventures by the river, in the forest and in the larger, alien human world of noisy towns. It is most often remembered as a jolly lark about friendship, and it is that, but in its tale of nature, of simplicity, of innocence threatened by a destructive and pompous progress, it conceals a deeper spirituality. It seeks to connect with the vanishing idyllic world, shares some of that renewed interest in the Western pagan tradition that informed some of the poetry, literature and art for a brief moment in the early years of the 20th century. In one chapter (often left out of some versions of the tale) Ratty and Mole find Otter’s lost son in the care of the god Pan, The Piper At The Gates of Dawn (a name and an image The Pink Floyd found inspiration in for their first album).

The Wind In The Willows has of course been animated and filmed many times. Nevertheless, we think Studio Ghibli could bring to it a unique vision and a renewed magic.

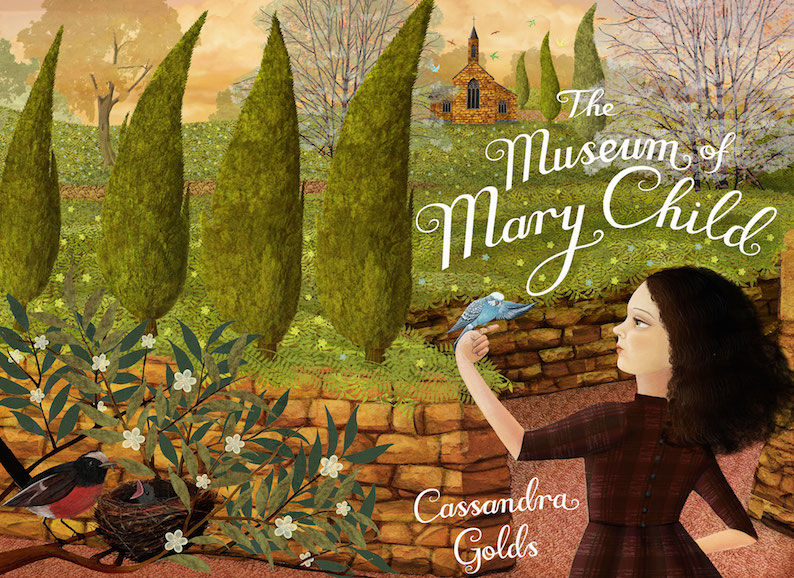

2. Cassandra Golds’ The Museum Of Mary Child

As we saw in Spirited Away, a story from Studio Ghibli can combine mystery and magic, myth and the surreal, wry humour with a sometimes frightening glimpse into the unknown. The Museum Of Mary Child, shares that sense of magic and danger. The tale of Heloise a young girl who escapes her cold, controlling puritanical Godmother and the dark secrets of the Museum she runs, into the wonders of a wide Dickensian city, both bourgeois and gothic, filled with melancholy, gloom and danger. Heloise is taken in to Old Mother’s Choir of Female Orphans, Waifs and Strays where she finds her voice, and her strength. Later, aided by clever mice and The Society Of The Caged Birds Of The City, who escape their cages each night and bring hope to the helpless, the formerly timid Heloise braves prison and madhouse to rescue a lost soul, and learn a secret. With her new found spirit, Heloise must go back to the haunted Museum, and uncover, for better or worse, the darkness that lies there. The Museum Of Mary Child is a tale of redemption, of how love overcomes. It is an adventure in a fantastic world, a mystery, a labyrinth. It is full of metaphysical and spiritual questions, to intrigue the hearts of adults, and yet is a beautiful and mysterious fairytale, to delight the hearts of children.

We think it reflects perfectly the spirit and the aesthetic of Studio Ghibli. Actually there isn’t even a Japanese translation in print, (hint hint Penguin Books), otherwise we suspect it would have been made already.

3. Lewis Carroll The Hunting Of The Snark (An Agony In Eight Fits)

Of course Lewis Carroll’s most famous work first published in 1865, Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, is another obvious choice for Studio Ghibli. Perhaps a little too obvious, with too much of a canonical familiarity that perhaps doesn’t lend itself to interpretation. Lewis Carroll’s grand poem of adventure, confoundment and spiritual mystery, from 1876, The Hunting Of The Snark, would be a more intriguing choice. Regarded as a nonsense poem, because of its invented words, puns and other poetical misdemeanours, its larger than life characters possessed of singular and peculiar traits and abilities, and several mysterious and undefinable monsters, it tells the story of an odd crew, a Bellman, a Bonnet-Maker, a Barrister, a Billiard-marker, a Broker, a Banker, a Butcher, a Baker, a Beaver and Boots – a shoeshine, that take ship following a blank map to a mysterious island, hunting for the Snark. The island, the same in which the monstrous Jabberwock was despatched in the poem Jabberwocky, published in Through The Looking Glass (1871), is also the realm of the Bandersnatch and the Jubjub. Upon arrival the crew go their different directions in search of the Snark, and like the Knights of the Round Table, in search of the Holy Grail, each has different encounters on the way. The Butcher and Beaver, mortal enemies, become best of friends. The Barrister dreams of prosecuting a pig for deserting its sty, with the Snark as defense counsel. The Banker is attacked by a Bandersnatch (a creature both fuming and furious or frumious, with a long neck and snapping jaws) and loses his sanity after failing to bribe the creature. At the conclusion of the poem the Baker cries out on discovery of the Snark, but has vanished when the others arrive.

Lewis Carroll when asked mostly said there was no meaning to the poem, though in one letter he agreed it was about the search for happiness. Many scholars, philosophers and literary analysts have found it to be about angst and order, an allegory for the voyage through life, a response to the fear of annihilation, the search for meaning in life. The quest for something grand, unknown, mysterious through adventure and peril. Through nonsense, through elaborate meaning that courts meaninglessness, through mystery and fantasy, eccentric characters and enigmatic monsters, something that in the hands of Studio Ghibli’s artists, re-interpreting and informed by their own mythological and fantasy traditions and inspirations, could be a marvel, an ecstasy rather than an agony.

4. William Shakespeare The Tempest

Japanese interpretations of Shakespeare have produced visual and dramatic masterpieces, most notably Akira Kurosawa’s Throne Of Blood, based on Macbeth, and Ran, based on King Lear, both of which transposed Shakespeare’s bloody tales of power, betrayal, madness and warring kings to feudal Japan. Studio Ghibli’s has more often found European fantasy traditions and locations (for instance in Howl’s Moving Castle and Kiki’s Delivery Service as magical and exotic backgrounds.

The Tempest tells the tale of Prospero, a great magician through the wealth of his knowledge, the rightful Duke Milan, deposed by his jealous brother Alonso, aided by the King of Naples, and set adrift in a boat with his baby daughter Miranda, cast ashore on a spirit haunted island whose denizens include the Spirit Ariel, and the ugly and monstrous Caliban, child of a malevolent witch, Sycorax, previously exiled to the island from Algiers, but who died before Prospero’s arrival. Caliban taught Prospero and Miranda how to survive on the island, and in return Prospero adopted and raised Caliban and taught him language and religion. Many years later, when the miscreant Caliban tried to force himself on the young Miranda, Prospero enslaved the creature. Freeing the Ariel from a tree where Sycorax had once trapped him, as reward Prospero also bound the spirit to his service.

Some years later Prospero divines that his usurping brother is passing in a ship; he summons a storm, a mighty tempest, that drives the ship aground. Antonio, Alonso and their families and servants are shipwrecked on the island. Prospero uses his power to separate and manipulate the castaways. Caliban plots to overthrow Prospero with two drunkard servants of the King whom he believes came from the moon. Prospero’s brother and nephew plot to take the throne from the King of Naples. While Prospero encourages romance between Miranda and Ferdinand, the King of Naples’ son, in a complex game he slowly draws all to him, and at the end has his enemies and his friends clearly in his power. You’ll have to watch it or read it tolearn the conclusion. (No 16th century spoilers here.)

It is a tale full of fantastic creatures, mysterious spirits and engaging characters, an exotic magical realm, elaborate plots, romance, vengeance, freedom, redemption and reconciliation. In the 1950s Forbidden Planet explored The Tempest as a Freudian Sci-Fi adventure, other interpretations explore it as a narrative of post-colonialism, Caliban, the monster, the cannibal, the dispossessed, becomes the indigenous revolutionary, the hero struggling against an overwhelming foreign power. Feminists have criticized The Tempest in terms of colonization and patriarchal domination. A 2010 film by Julie Taymor saw Helen Mirren take the role as Prospera, but the change did little to alter the dynamics of the story. Miranda, the only female character (others are mentioned, and the spirit Ariel sometimes takes female forms) is seen as totally under the control of her father, utterly subordinate, essentially a pawn, with no will or purpose but to remain chaste. And yet, does not the entire storm swirl around her? Caliban’s resentment, Prospero’s hopes, Ferdinand’s love. In her marriage, will she not eventually become queen?

In many ways a Studio Ghibli interpretation could unify a fascination with grand historical drama and the exploration of a vision of European as an exotic world imbued with magic. With Miranda as the quiet centre of the story, the catalyst that brings about change, redemption, reconciliation amongst the powerful forces around her, she could be a heroine like Kiki or Sophie. Again, with their extraordinary vision, a Studio Ghibli The Tempest we think would be fantastic.

There are so many others that could be mentioned. Some a perfect fit, some not so. Is there another historic aerial adventure like Porco Rosso? Could Studio Ghibli do Philip K Dick’s The King Of The Elves? Disney seems to have dropped the ball on that for several years running. What do you think? If you’re a fan of Howl’s Moving Castle, Kiki’s Delivery Service, The Tale Of The Princess Kaguya, My Neighbor Totoro, Porco Rosso, Tales From Earthsea, Spirited Away and their many other great films, what would you like to see? In 2014 they produced in collaboration with Polygon Pictures an anime series, Ronia The Robber’s Daughter, a story of rival families in a medieval world, based on the book by Astrid Lindgren. Perhaps they could do a good series of Brian Jacques, Redwall? So many wonderful stories so little time. Actually, we strongly recommend you stop reading this and go and watch a Studio Ghibli film right now. If you like, when you are finished, come back, tell us what you think.