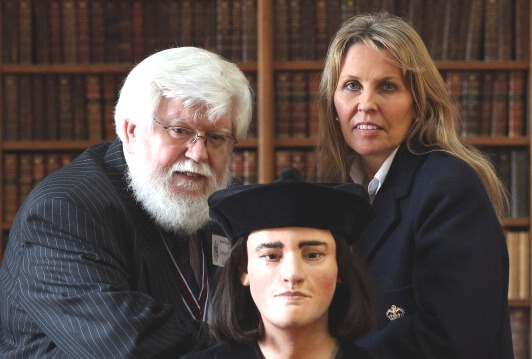

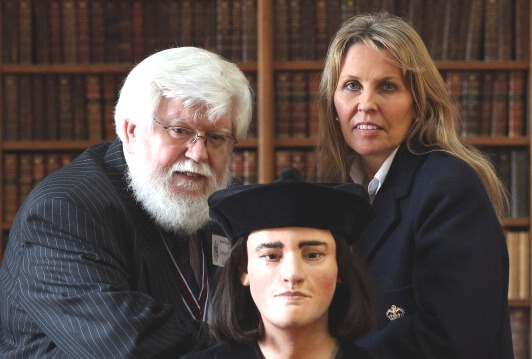

Five centuries on and even the very bones of Richard III are causing controversy. In 2009 screenwriter and secretary of the Scottish branch of the Richard III society, Philippa Langley, decided it was high time we found the king who had been missing for a few centuries. After reading the results of Dr. John Ashdown-Hill’s research and his discovery of the DNA of Anne of York, Richard III’s sister, and years of her researching on her own, Philippa decided they not only had the means to find Richard III, but they could finally identify him if they did.

The University of Leicester warned Philippa that the chances of finding the remains of Richard III were slim. They had agreed to take on the project on the basis they were investigating the Greyfriars site and were careful to maintain a dubious air. They found a skeleton on the very first day of the dig, the 25th of August 2012. They looked on with a mixture of bemusement and scepticism as Philippa insisted the royal banner of Richard III be draped over the box the remains were packed into, which was carried, with quite some reverence, by John Ashdown-Hill.

On February 4th 2013, the results of the archaeological dig in Leicester, a joint project comprising of Leicester University and the Looking for Richard project, were revealed to the public. They had indeed discovered the remains of King Richard III, only 680 millimetres below the surface of a car park in Leicester, where he had lain since 1485.

Suddenly the university had dubbed the Greyfriars dig “The Search for Richard III” and were exalting in their triumph. It was an amazing historical discovery. But it was not possible without the hard work of the members of the Looking for Richard project, which the media was largely ignoring.

A frenzied debate began over where his bones should be interred. When the human remains were discovered, the University of Leicester applied for an exhumation licence from the Ministry of Justice. The understanding was the remains would be re-interred at St Martin’s Cathedral Leicester, it is after all standard archaeological protocol that exhumed remains be re-interred in the nearest consecrated ground. The Richard III society stated it would be happy to work with whichever cathedral was chosen to receive the remains. Looking for Richard team members including Philippa Langley publicly stated they were happy for Richard to remain in Leicester.

Then the Plantagenet Alliance was formed, a group of Richard III’s descendants. They requested a judicial review over the lack of consultation of the issue of where the monarch would be laid to rest. The group wants the king’s remains to be re-interred in York Minster as they believe it was the monarch’s wish. The University argues that Leicester City Council, the landowner, had given permission for the dig on the basis that he would be re-interred in Leicester, re-interment on the nearest consecrated ground is in keeping with good archaeological practice and that plan for re-interment in Leicester Cathedral was clearly stated and unambiguous at the start of the project. Furthermore there is no obligation to consult living relatives where remains are older than 100 years. The Search for Richard III press pack, however, declines to mention the £10 million that was being spent on the tourist centre in Leicester.

Should Richard be buried in York? As historian David Baldwin told us “no member of his immediate family sought to have his body removed to York (or anywhere else) in the months and years after 1485.” Although some speculate that Richard would have been planning to be buried in Westminster with his wife Anne Neville that is probably not the case. Anne had died five months prior to Richard’s death and he was planning a second marriage. He was still young enough to father more children and it is far more likely he would have been buried with his second wife. Unfortunately Richard didn’t get a chance to place a memorial over her resting place and Anne Neville lies in an unmarked grave in Westminster. There was no memorial to her until 1960, when a bronze tablet was erected on a wall near her grave by the Richard III society. We have no firm evidence of where Richard III wanted to be buried. We can only speculate that he would want to be buried in York.

This recent statement by David and Wendy Johnson of the Looking for Richard project sheds some more light on how the University of Leicester has behaved since the remains were discovered. Firstly they proposed to put Richard III’s remains on public display in the Leicester Cathedral. This was contrary to the original agreements between the Looking for Richard project and the authorities in Leicester, it also breached the terms of the Ministry of Justice exhumation licence. The licence clearly stated that before reburial the remains shall ‘be kept safely, privately and decently by the University of Leicester Archaeological Services’. A spokeswoman for Leicester Cathedral stated the church would not take part in any public showings, saying “Scientists may have a reason for seeing them, but that is different from public display in the cathedral.” The Leicester Mercury took an online poll that showed 69% of respondents were opposed to public display. The plans were quietly dropped.

Furthermore David and Wendy Johnson outline the initial agreement between Philippa Langley and the University of Leicester, where Philippa was named Client in the project, and established her as Custodian of Richard’s remains. A clause stated that Any human remains which are positively identified as those of Richard III will, after specialist DNA, osteological and archaeological recording, be transferred to the custody of the Client and/or the Client’s representatives for reburial. The university had no intention of honouring the clause, arguing it was not a signed agreement, simply a project management tool, and were therefore not required to transfer Richard’s remains to Philippa’s care.

On 8 May 2013 a document was distributed to the Fabric Group (one of three groups formed by Leicester Cathedral to facilitate the interment process) telling them they were required to ensure the remains are conserved for posterity and accessible for future study. Is it any wonder the group baulked at the idea of allowing the university to dig Richard up whenever they felt like it to have another look at his bones? The idea is abhorrent.

The clause that named Philippa Langley Client also stipulated that she would then place the remains in a carefully selected place of Catholic sanctity where a cycle of continual prayer and worship would spiritually prepare the remains for re-interment. There has been some debate over the fact that the Leicester Cathedral is Anglican. John Ashdown Hill told historical reconstruction researchers Lost in Castles that “the former Dean of Leicester was very open to discussion on this subject, and was happy to involve members of the Catholic hierarchy, and to use a Catholic liturgy for the reburial.” This may have perhaps settled the matter, except the Cathedral then decided that they would use a marble slab for Richard’s memorial and not a tomb. Lost in Castles had already submitted a design for a tomb which received wide public approval, although they warned it was to be considered along with others. The Lost in Castles design is an elegant and understated design fit for a medieval king. Another poll was run by the Mercury where 91% of respondents demanded Richard III should be honoured with a tomb. In the face of overwhelming public opposition the cathedral backed down.

This is Leicester’s proposed design for a tomb.

The Richard III Society withdrew their £40,000 contribution after being confronted with this modern monstrosity.

It’s not surprising this long drawn-out battle is being labelled the “Second Wars of the Roses”. Richard III’s remains are still languishing in Leicester, over a year since they were exhumed. Leicester’s case for control of Richard’s bones may be legally sound, but the Plantagenet Alliance have been successful in their bid to challenge Leicester’s decisions. In August Mr Justice Haddon-Cave gave the group permission to launch a High Court challenge in what he described as an unprecedented case. He said depth of public feeling raised an obvious duty to consult widely over how Richard should be reburied. The Judicial Review hearing will take place on the 26th November 2013.

Read our interview with the historian who traced Richard’s DNA Dr. John Ashdown-Hill.