It was early evening in late November. The lights were already on and the curtains drawn in a vain attempt to illuminate and brighten what had been a dank and dreary autumn day, which in itself, although unusually mild, promised only the prospect of many weeks of cold, dark discomfort ahead.

A small black and white television in the corner of the living room had been the main focus of my parents’ attention on that Saturday afternoon, or rather what it was displaying, to be more accurate. It was now a little after 5pm and the football scores had been dutifully noted down by my father who now proceeded to screw the paper he had been writing on into a small ball, whilst at the same time declaring that we were going to remain poor for at least another week . My mother seemed rather upset about something that had happened thousands of miles away to some American called Kenny, or was he John? I really found this hard to understand, but I did grasp the fact that he had been shot and that this fact alone had made my mother cry and also threatened to disrupt our normal family routines. However, my mother decided that there would be time enough to hear more about this unfortunate man’s shooting, and, as it had been promised that I could watch a new children’s television programme starting at 5.15pm, I now positioned my chair in front of my father and awaited the start of Doctor Who.

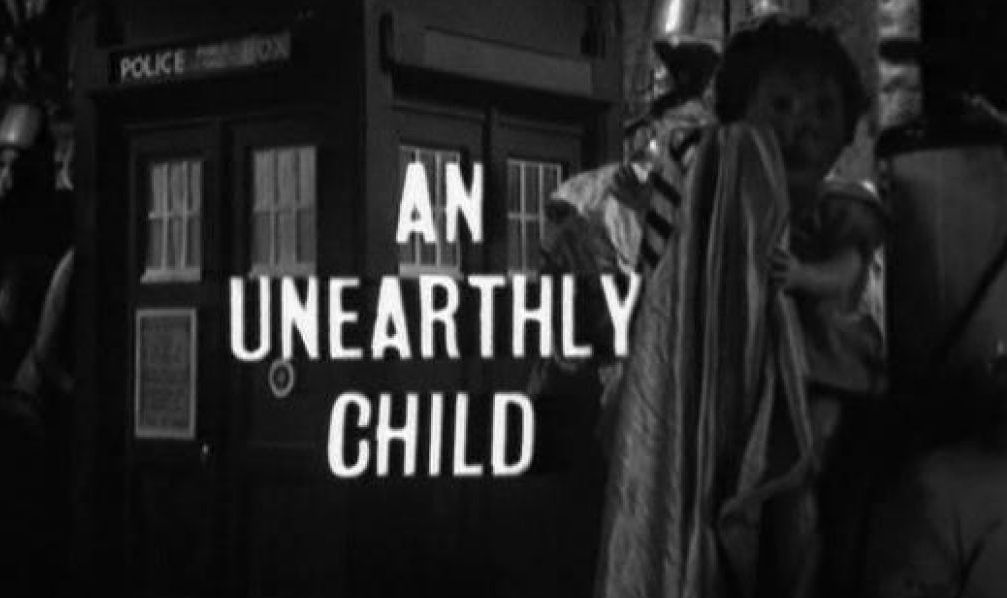

It was, of course, Saturday the 23rd of November, 1963 and at 5.16pm on BBC television the remarkable, but now very familiar theme music to Doctor Who began to play, along with some strange waving images which I found disturbingly frightening. After this initial shock, the rest of the programme seemed a little dull. Where were the promised adventures in space and time? Did I really want to be reminded of school and teachers? Then, just at the end, it promised excitement. The small box that the teachers, a young girl and an old man had all entered was now flying through space and hurling the occupants around its interior, reducing them to unconsciousness before landing in a desolate, deserted landscape. But wait. What was that menacing shadow now appearing and moving towards the spacecraft and its helpless inhabitants? There was no time for the question to be answered as that strange music, now less frightening and intriguingly compelling, was now emanating from the television screen, along with the title of next week’s programme, The Cave of Skulls. Good, it was going to continue and I was sufficiently hooked to want to see the outcome of what happened next to our intrepid space travellers and as to who, or what, that shadow belonged to and what did it mean? A format that children of my age had grown used to with the weekly cliff-hangers of Saturday morning cinema.

It was, of course, Saturday the 23rd of November, 1963 and at 5.16pm on BBC television the remarkable, but now very familiar theme music to Doctor Who began to play, along with some strange waving images which I found disturbingly frightening. After this initial shock, the rest of the programme seemed a little dull. Where were the promised adventures in space and time? Did I really want to be reminded of school and teachers? Then, just at the end, it promised excitement. The small box that the teachers, a young girl and an old man had all entered was now flying through space and hurling the occupants around its interior, reducing them to unconsciousness before landing in a desolate, deserted landscape. But wait. What was that menacing shadow now appearing and moving towards the spacecraft and its helpless inhabitants? There was no time for the question to be answered as that strange music, now less frightening and intriguingly compelling, was now emanating from the television screen, along with the title of next week’s programme, The Cave of Skulls. Good, it was going to continue and I was sufficiently hooked to want to see the outcome of what happened next to our intrepid space travellers and as to who, or what, that shadow belonged to and what did it mean? A format that children of my age had grown used to with the weekly cliff-hangers of Saturday morning cinema.

Although this first programme received praise, those that followed received criticism for simplistic and clichéd characters and dialogue regarding the cave dwellers that appeared during episodes 2, 3 & 4, and viewing figures were also perceived as unsatisfactory by BBC bosses. As a consequence of this the men in suits at the BBC decided it would be better to cancel Doctor Who rather than continue, as it was, for its time, an expensive programme to produce, with a running time of less than 25 minutes and was, after all, merely for children’s television.

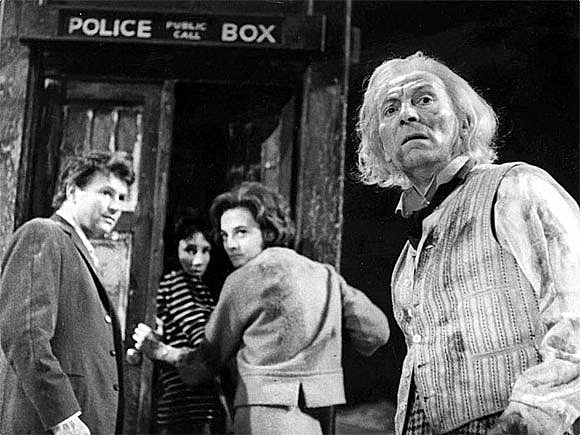

Due to serendipity rather than any great planning, the second block of Doctor Who programmes would feature the introduction of The Daleks, who were the brainchild of Terry Nation. Verity Lambert, the producer of Doctor Who and the BBC’s only female television drama producer at that time, campaigned hard to be allowed to press ahead with this second batch of Doctor Who adventures. She certainly had a passion and a belief in the project she was directing and also for its star, William Hartnell, but she also knew that an axing of this programme could also mean the end of her aspirations at the BBC and would also be a severe blow to women in general who were trying to break into male dominated and misogynistic establishments like the BBC at that time.

The second batch of Doctor Who programmes went ahead and the Daleks proved to be an instant success. Doctor Who was saved and both Verity and the programme went on to attain new heights.

Countless children would now make their way to and from school, annoying many adults along the way, by waving their arms around their foreheads and shouting “exterminate” as loudly as possible, and yes, I am proud to say that I was one of them.

In hindsight it seems incredible that Doctor Who could have been axed at such an embryonic stage of its programming. What ratings did they expect when it débuted the day after the assassination of President Kennedy, and pray tell what dialogue would they have liked cavemen to have? No, I think the truth of the matter was that those in charge of the BBC at that time were the true Neanderthals. They were looking for any excuse to prove the programme a failure purely in order to validate their point that woman were fine as secretaries and in making the tea, but could and should not be trusted, or placed, in positions of decision making regarding the production of BBC programmes.

Verity Lambert’s success smashed that view forever and she quickly became sought after to head up other projects, leaving Doctor Who in 1965 to go and produce Adam Adamant Lives for the BBC, before eventually leaving the BBC in 1969 to produce Budgie for London Weekend Television.

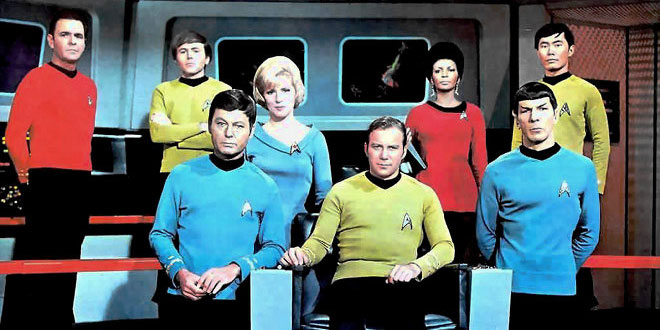

In the summer of 1969 the BBC starting running the first series of Star Trek and placed it in the slot previously allocated to Doctor Who; 5.15 pm on a Saturday evening. I broke ranks and became a Star Trek fan. Admittedly they still had to throw themselves around the bridge when the Enterprise came under attack in much the same way that any malfunction of the TARDIS required the doctor and his companions to energetically bounce from side to side whilst shouting something along the lines of: “The controls have jammed” or, “I can’t stop it” and “Doctor, what’s happening”?

Whilst Doctor Who was still being made in glorious monochrome, Star Trek was available to be seen in colour. The adventures of Captain James T Kirk and the crew of the Enterprise seemed to be literally light years ahead of the doctor. As a youngster I was dazzled by the extravagant American production standards employed in Star Trek. It was fast, exciting, and colourful with a central hero who was not only a commander, but was young, good looking, heroic and always victorious in saving any combination of his crew, the ship, the planet or the whole universe. Despite the many trials and tribulations Kirk endured as Captain of the Enterprise, he always managed to find the time to woo and win a never ending succession of beautiful, young women, be they crew members or aliens that always looked incredibly human. The good Doctor in comparison was an old man who never got the girl or indeed even showed any inclination to want to get the girl. To a teenage boy who had grown up during the “swinging” 60’s and the “dawning of the age of Aquarius”, it was pretty much a no brainer as to whom my role model was going to be. As Nena sang in 99 Red Balloons: “Everyone’s a superhero. Everyone’s a Captain Kirk”. Somehow everyone’s a Doctor Who just wouldn’t have sounded right, would it?

Star Trek of course contained many clichés. Woe betide any security team that beamed down to any hostile environment with a detachment of high ranking officers, for instance, as their chances of even making it to the opening credits was minimal. Still, it did always gives Bones the opportunity to give a perfunctory examination of some poor man’s body before declaring; “he’s dead Jim”.

In time I drifted back to Doctor Who and continued to watch it alongside the various versions of Star Trek, both genres seeming to fill the gaps between their respective reinventions.

Doctor Who is now, of course, no longer a children’s television programme in the true sense of the word, but then perhaps it never was. It was always going to appeal to an older audience as well as children and that’s why it was easy to grow up with. It may have taken longer than Star Trek to reboot itself into a smarter, technologically savvy and altogether cooler version that is more in keeping with the tastes of the 21st century, but this has also allowed the demographic that grew up with the original Doctor Who to take the same journey without becoming lost in some youth orientated streetwise version of the good doctor.

Although the contrasts between the Doctor Who of 1963 and the current version may seem vast and many, they probably both fit and reflect the ages they were and are being viewed in.

The original Doctor Who now looks very dated with its shaky, simple sets, some clichéd scripts and fluffed lines, but it fitted the times perfectly and was, of course, subject to editing restrictions which would be thought archaic by today’s standards. By the standards prevailing in the Britain of 1963 it was, believe it or not, very glamorous and exciting for a television programme, especially one aimed at children.

Although Macmillan had said some years earlier that we had “never had it so good” and London was starting to swing, Britain in 1963 was still suffering the effects of a war that had finished nearly 20 years earlier. The urban landscape still showed the physical scars of the conflict, as did some of the population. We also bore the mental scars of losing an Empire whilst winning a war and the economy was still crippled from the effects of the conflict. Yes, things were on an upturn and increased sales of consumer goods were both triggering an economic revival and improving standards of living for those that could afford such purchases. I remember however that the winters were cold, there were no double glazing, and coal fires were tricky to get going and were dirty, ineffective and smelly. Fogs were frequent, hurt the eyes and made you cough, whilst cars, lorries, buses and chimneys seemed to spew out a never ending pall of black, acrid smoke. A teacher’s physical cruelty with a cane, stick, board rubber or slipper could be equally matched with their mental cruelty and their ability to insult and humiliate. All clothes were hand washed and put through a mangle and then left on the washing line to freeze solid. Ice had to be scraped from the inside of bedroom windows when waking in the morning, household telephones were still thought of as a luxury for the well-off and you stayed at the dining table without speaking until the meal was finished and you were excused.

Yes, Britain in 1963 could seem a bleak place to be growing up in, but it was also an exciting place for a child and Doctor Who, despite its drawbacks, seemed wonderfully glamorous to a young boy growing up during this age and I feel strangely privileged to have been viewing it from the start.

Doctor Who images ©BBC