As night drew in over the battlefield at Waterloo on the 18th June it served to not only signal a victory for Wellington and Blücher over Napoleon, but to also provide some visual respite from the grim realities of war that had accumulated throughout a day that had seen carnage, courage, honour, horror, duty and death make strange alliances and walk hand in hand through a foreign field.

The battlefield was now invisible in the shadow of the night, but the pitiful cries and moans of wounded men still echoed across this darkened landscape, interrupted only by the occasional discharge of a pistol to either warn looters and scavengers away, or as a final act of comradeship between soldiers when all hope was lost and only a slow and painfully torturous death awaited.

These sounds of human torment were given company that night by their equine companions who had, unlike their human masters, no hope of salvation and no perception, or knowledge, as to why they were being tormented with such pain and misery. Their pitiful neighing punctuated the night air and formed a macabre accompaniment to their master’s songs of death which now hung over the whole battlefield, but were now fading in volume, ever so slowly, but surely, as the night of the 18th turned into the early hours of the 19th June.

Many horses that were still able to stand, but limping, were seen desperately trying to find a blade of uncontaminated grass to eat, but all in vain and to no avail. Others gathered together in some strange form of invalid herd as if to try and sympathise with each other’s pain. Some collapsed horses tried feebly pulling at the grass around them, then, despite their horrific wounds, they would try to rise, but always fall back, lift their heads, look wistfully around, try to rise again and then give up, quietly lying down and at last expiring.

The sound of a galloping horse could often be heard as, mad with pain, it kicked and cavorted over this gore soaked field, often trampling over the wounded, in a dance macabre of futility and desperation until its energy was no more and it too finally lay with the rest, snorting and neighing until succumbing to the inevitable.

Out of 60,000 horses on the field of battle that day at least 7,000 were killed or wounded, with at least one estimate putting the figure as high as 20,000. With veterinary science being even more primitive than the butchery that was inflicted upon many of the wounded soldiers under the heading of medical care, the fate of a wounded horse usually depended on a soldier having the courage to put it out of its misery. Courage it was, as many soldiers were more affected and distressed in witnessing the fate of these animals as seeing their own comrades killed or wounded.

Some however did survive, through the efforts of James Paterson of the Scot’s Greys, who tended to many horses in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Sir Astley Cooper was another individual who had been moved by the plight of the Waterloo horses and bought 20 bad cases that had been patched up enough to survive their wounds, but no more. Cooper was a noted surgeon and, after shipping the horses to England, he set about removing musket balls, grapeshot and stitching sabre cuts from their bodies and limbs, spending many months in this surgery and general rehabilitation. Against all odds he was successful and these horses were soon turned loose in the fields, where they exhibited unusual behavioural traits from their service at Waterloo. They would gather in a line and advance to a charge across the field, halt, retreat and then gallop about excitedly. They followed this pattern most mornings, but were now obviously happy despite this exhibition of behaviour that we would probably now recognise in humans as a form of post-traumatic stress disorder. Another horse that had been rescued from the mass killing fields of Waterloo would put himself on alert for a charge upon the slightest noise and start, as if to avoid a sabre cut. With no further record of this horse’s rehabilitation, one can only hope that he too soon found himself galloping in the fields with his companions.

Wellington wrote his victorious report of the battle (which would become known as The Waterloo Dispatch) on the 19th June and entrusted the task of delivering this letter to the Prince Regent in London to Major Henry Percy. Percy was also instructed to carry with him two captured French Imperial Eagles (the equivalent of British Regimental Colours) and place them at the feet of Prince George.

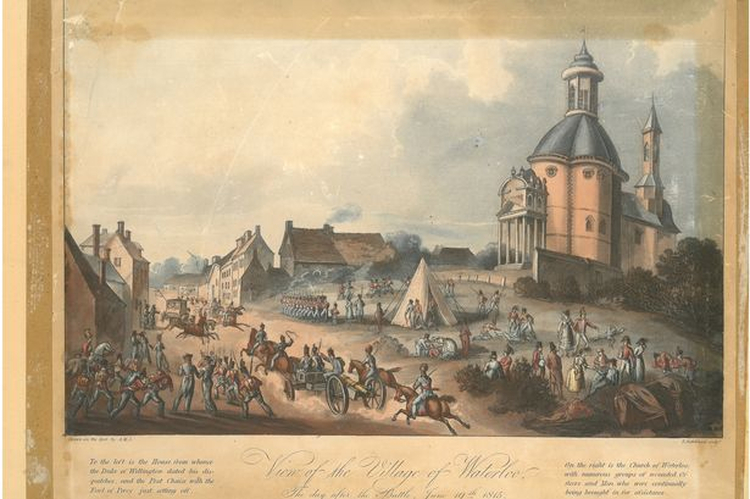

Percy travelled by horse-drawn post-chaise from Brussels to Ostend, where he boarded the Royal Navy sloop HMS Peruvian. Luck and wind were against Percy however, as the Peruvian was becalmed mid-channel. Despite already enduring an arduous journey to reach this far, and still without a change of clothes from his muddy and bloodstained battle tunic, Percy had no option but to allow the ship’s captain to lower his gig, select four strong rowers to accompany them and for all of them to commence rowing to England.

Percy, who was by now completely exhausted, landed at Broadstairs, Kent at around 3pm on the 21st June, commandeered another post-chaise and began the dash to London. Percy’s route took him through Canterbury, Sittingbourne and Rochester, before finally arriving in London at around 10pm.

Locating the Prince Regent at a soirée hosted by Mrs Boehm at 16 St James Square, the dishevelled Percy apparently burst in shouting “victory! victory! Bonaparte has been beaten”.

Percy was made a Colonel on the spot and finally allowed to retire to bed.

56 newspapers were regularly published in London in 1815, but not one of them sent a reporter to cover Wellington’s campaign. On the very day these newspapers carried the news from Waterloo, courtesy of Percy, they also carried advertisements for a brand new steam ferry service operating from London – just too late to save Percy a 15 mile row.

Now, 200 years on, two actors in period uniform will carry “The New Waterloo Dispatch” as they re-enact the journey and will leave the battlefield at Waterloo in a post-chaise on Thursday 18th June and travel to London.

Numerous commemorations are being held across Kent, as well as in London, Belgium and Germany to remember how the news of this victory spread.

Doubtless Wellington, Blücher, Napoleon and the men who fought with them at Waterloo will be justly commemorated and remembered this week. Who, though, will remember the horses?

Neil Kemp is a keen and passionate amateur historian and prize winning photographer who lives in Margate, on the North Kent coast in the United Kingdom. Before retiring he worked both with and at Margate Museum, overseeing budgets on a number of historical projects.