The First World War is viewed as the first truly mechanised war and the horrific effects of gas, artillery and machine gun against the frailties of human flesh have been well documented over the last century. However, it was also the war of the horse: from mounting cavalry charges and pulling heavy guns to aiding the transportation of the wounded and dying to hospital and the more mundane tasks of packing and hauling supplies and ammunition.

At the outbreak of WWI, the British Army had 25,000 horses at its disposal. Whilst this may seem to be a significant number, it was estimated that many, many more would be needed in order to adequately equip the British Army for war. Earl Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, reasoned that around six times the number of horses that the army currently possessed was held in private ownership throughout Britain and that these animals should be thought of as the army’s reserves. Thus began Kitchener’s impressment of horses, which involved the compulsory purchase of any horse that the army deemed appropriate for its uses. Very often, the first an unsuspecting owner would know about the likelihood of losing their animal would be to answer the door to an army sergeant who then handed the bemused and often distressed owner some gold sovereigns whilst their treasured possession was being led away. During the first year of the war, Britain was stripped of its shire horses and riding ponies. Many of these animals were regarded by their owners as family pets and their requisition caused much anguish and hardship amongst the civilian population. Even horses that had a legitimate working function were not spared: one family owned bakery had its two horses that were used to pull the bread wagon forcibly removed from their stable. The baker’s wife was so distraught that she threw the forty gold sovereigns she had been handed as compensation onto the garden claiming it to be “blood money”.

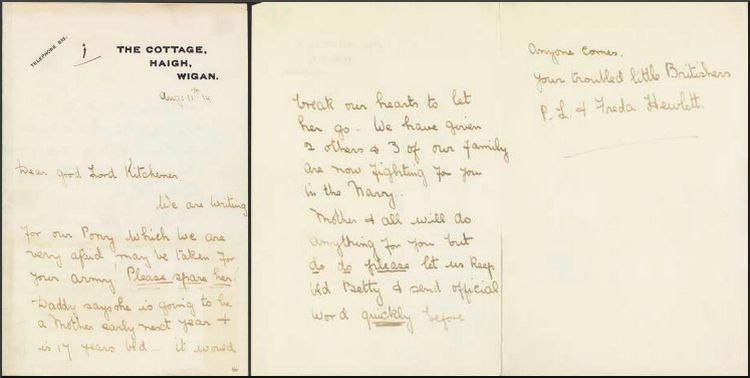

One heartfelt letter from a young girl, pleading Kitchener not to take away her small pony, at last prompted a response. Kitchener wrote back and declared that he had issued instructions that no horses under 15 hands were to be taken by the army, thus sparing the girl’s small pony. In truth this was nothing more than a massive propaganda exercise as the army did not want horses under 15 hands in any event, the perception of an ideal height being 15.1 hands or slightly above.

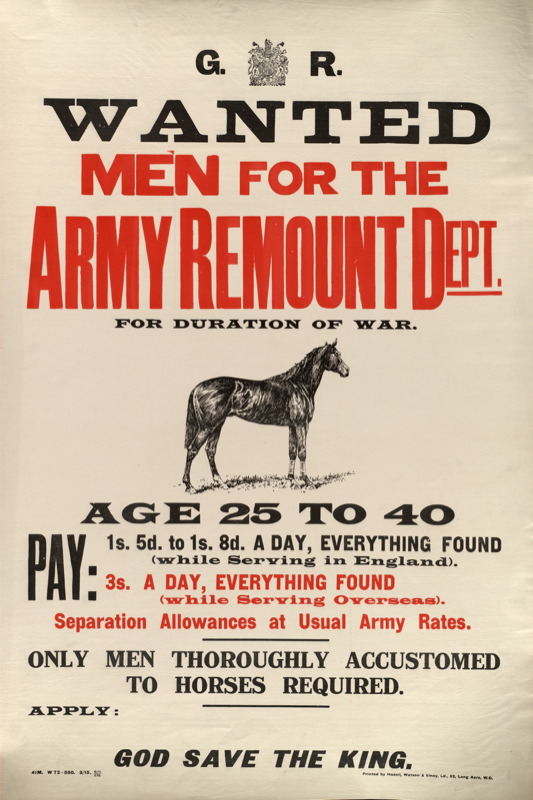

The huge logistical exercise involved in dealing with such a large number of horses led to the expansion of the Army Remount Service, which had first been established in 1887, and additional army remount depots were developed at Shirehampton (Bristol), Romsey (near Southampton) and Ormskirk (near Liverpool). One other depot, at Swaythling (Southampton), was built as a transportation centre and received horses from the other depots in preparation for onward shipment overseas. All of these depots required paddocks, the building of stable blocks, barracks and veterinary services, to enable the horses at these depots to be checked over and cared for in preparation for their transportation to France. Although there remains a perception, by some, that the animals were not well cared for in these centres; in actuality the care they received was very professional and had much improved since the British Army’s engagements a few years earlier in the second Boer War. The army had lost some 300,000 horses during that conflict and many of those deaths could have been avoided with better feeding and general care. In short, the army had lost many of its horses through neglect and it now realised that these animals were far too valuable an asset to treat so carelessly and the facilities at the remount depots now reflected the army’s concerns for these animal’s welfare. Although the Army Veterinary Service had been established in 1796, it was not until 1903, with the formation of the Army Veterinary Corp, that a greater uniformity of care prevailed due to the amalgamation of previously disparate units. Thus (in the main), uniform rules of procedure and care now oversaw all aspects of the horse’s well-being during their time at these depots.

Once transported to France many of these horses were initially used as traditional cavalry horses, the military commanders still looking backwards to past conflicts where cavalry charges were a normal and vital aspect of any conflict. This thinking still being prevalent, despite the fact that, by the start of WWI, Britain, amongst all of the warring factions, was probably the most advanced nation in terms of mechanisation. The initial stages of the war did indeed see a traditional role for cavalry who were able to engage the enemy over open terrain and some skirmishes even saw cavalry unit against cavalry unit. The use of barbed wire and the machine gun soon changed all of that, but not before elements of British Cavalry had been horribly slaughtered in brave but futile and reckless charges against such fortified positions. Eventually the carbine replaced the lance and the sword and the horse then became a means of transport to deploy troops to a combat zone, who were then able to dismount and form either a defensive or an offensive line against the enemy. This also required a different and more intense training of the horse that had to be conditioned to the sounds of modern warfare. The increase of fixed defensive positions, which involved the digging of trenches and seemingly endless rows of barbed wire, further diminished any effective combat role for the horse and many were reduced to hauling artillery guns or packing.

At the end of the first year of war, the remount service had mobilised over 500,000 horses, but it was now realised that mules were needed even more urgently as these animals could be used for the arduous work of packing and hauling to a far greater efficiency than horses. They could carry more than a horse of the same size, they required less feed and their endurance, especially over rugged terrain, was far greater than the horse. There was just one catch: the expression, “stubborn as a mule”, could be accurate and to the straight-laced officers of the British Army this would not do at all. In truth, all that was required was a more patient handling of the animal. As one handler declared, “horses are dogs, mules are cats”, believing them to be independently minded rather than inherently stubborn. Where a horse might respond to a whip, a mule would not and, although it took some time, a kinder and more patient approach began to show the mule’s effectiveness in all of the theatres of war it was required to operate in.

Despite Kitchener’s impressment programme, the army still needed more horses and mules, so Britain turned principally to America in order to fill the gap. Soon, a regular supply of one thousand horses a week were being landed at Bristol’s King Edward Dock and transported the short distance to the remount depot at Shirehampton. The depot soon held as many as 5,000 horses and with a constant stream of horses arriving from the USA, an overflow facility had to be found. The depot at Ormskirk, near Liverpool, was also full and therefore unable to accept these overseas imports. The sea around the approach to Southampton was a haven for U-Boats, making it far too dangerous a proposition to contemplate travelling the extra distance around the coast to this facility. The only practical recourse available to the army therefore involved further requisitions, this time of suitable farmyards within reasonable travelling distance of Shirehampton. Eventually, 12 mule depots were established on private farms and land, which had been requisitioned by the army, and these were used to provide rest, recuperation and training for the animals before shipment to Swaythling.

One such centre was at Bratton Court, Somerset and the compensation for the requisition of the land was 30 shillings a week (around £140 at today’s values), which doesn’t sound a great deal but add to this that an additional two shillings and six pence was given for every mule that arrived at Bratton Court. This made the final figure around £5,500 per week at today’s values, a considerable sum. Compensation was certainly one area where the army operated a very fair and efficient system with a figure of over 36 million pounds being spent on the horse-purchasing programme during the course of the war.

The logistics involved in providing facilities for such a large number of animals also provided an unexpected boost to the empowerment of women, with one centre at Russley Park, Wiltshire, being run entirely by women. Originally designated as a stud for “top brass” chargers, it never fully achieved this role and became predominantly a training and rehabilitation centre for officers’ cavalry horses. The women who ran the centre were all upper-class young girls who caused shock and outrage amongst the local population by not only wearing trousers and dressing as men, but by sitting astride the horses when riding them out rather than using the traditional side-saddle. The queen had, as late as 1913, tried to ban women riding astride in Hyde Park and, at the horse show held at Olympia in 1914, the king refused to watch any woman that came into the arena riding astride. The care of horses was just one of many roles that women were able to excel at during WWI and this undertaking of tasks, previously thought of as only suitable for men, undoubtedly hastened a long overdue breakthrough in achieving greater equality for women.

Once overseas these animals, whatever their function, had a very hard time. Death was everywhere: with machine gun, artillery, gas, plane, barbed wire, mud, exhaustion, overwork and disease claiming many lives. By the end of the war some 484,000 British Army horses and mules had died – one for every two men. The riders or handlers of these animals, many of them hardened army veterans, became hopelessly attached to their charges in many cases and, whilst being seemingly immune to the slaughter of so many men around them, became distraught at the loss of their treasured equine companion. The following poem, A Soldier’s Kiss, by Henry Chappell, eloquently epitomises this feeling.

Only a dying horse! Pull off the gear,

And slip the needless bit from frothing jaws,

Drag it aside there, leaving the roadway clear,

The battery thunders on with scarce a pause.Prone by the shell-swept highway there it lies

With quivering limbs, as fast the life-tide fails,

Dark films are closing o’er the faithful eyes

That mutely plead for aid where none avails.Onward the battery rolls, but one there speeds

Heedless of comrade’s voice or bursting shell,

Back to the wounded friend who lonely bleeds

Beside the stony highway where he fell.Only a dying horse! He swiftly kneels,

Lifts the limp head and hears the shivering sigh

Kisses his friend, while down his cheek there steals

Sweet pity’s tear, “goodbye old man, goodbye”.No honours wait him, medal, badge or star,

Though scarce could war a kindlier deed unfold;

He bears within his breast, more precious far

Beyond the gift of kings, a heart of gold.

By the end of the war, the overall cost to the equine population of the nations involved in the conflict consisted of 8 million horses, mules and donkeys having been killed. On the western front many had died, caked in mud, by being simply too exhausted to breathe. Britain had around 900,000 horses overseas at the time of the armistice and, whilst the repatriation of soldiers proceeded with as much haste and efficiency as could be made possible, the return of horses was viewed as a needless encumbrance to this priority. Far fewer horses were going to be required for Britain’s peacetime army and it can be argued that it was with cynical reasoning it was deemed more productive to leave most of them where they were, rather than down to the bumbling incompetence of those responsible for their repatriation. The reward for the majority of these animals was therefore to either be auctioned off and to spend the remainder of their days toiling in a foreign field or, for those animals in less than good condition, to be slaughtered, with their meat being used both to boost domestic food stocks and to help feed the tens of thousands of POW’s whose welfare was the responsibility of the victorious nations.

One man who was outraged at this deplorable treatment of animals who had served Britain so well was John Seely (Baron Mottistone). Probably better known as “General Jack”, Seely wished to repatriate his own horse, Warrior, who had survived the whole war being ridden by Jack without injury, culminating in his participation in one of the last major cavalry charges ever, at Moreuil Wood in March 1918. His exploits during the war led to Warrior being dubbed as “The horse the Germans couldn’t kill”.

Seely successfully brought Warrior back to his home on the Isle of Wight, but was so incensed at the treatment being given to those horses that remained overseas that he wrote to Winston Churchill demanding that something be done regarding the intolerable delay in their transportation home. Churchill, who had been given the post of Secretary of State for War in January 1919 and was therefore ultimately responsible for the speedy demobilisation of all fighting and ancillary units, was furious. As an ardent animal lover himself and having served at the western front, he was very well aware of the sacrifices that these animals had made for Britain and their current treatment appalled him. It is mainly through the direct efforts of Churchill that around 60,000 horses were eventually returned to Britain, still a pitifully small number of the total that had survived the war only to be discarded by the army in the most heartless way conceivable.

The Army Veterinary Corp must be excluded from such criticism, having provided sterling service to the two and a half million animals it treated during the course of the war, with 80% of all injured animals cared for by the corps being able to return to duty. In recognition of the veterinary corps service throughout the war, the “Royal” prefix was granted to them on November 27th 1918.

After the First World War the role of the horse changed forever due to the increased mechanisation of the modern world and, despite its future deployment in areas of rugged or inhospitable terrain, it would never again play such a significant part in military conflicts. Science has given man easier and more direct means to kill one another without involving the horse and for that, at least, we should be grateful. This noble beast will never again have to suffer the horrors of modern warfare only to be slaughtered upon the expiry of its usefulness by the very people it had trusted and had given its all for.

Overdue recognition to the service and sacrifice that all animals involved in British conflicts have made came with the unveiling of the Animals in War Memorial in Park Lane, London, in 2004. The second of two inscriptions written on the memorial simply reads: “They had no choice”.

Dover Castle War Horse Exhibition

Neil Kemp is a keen and passionate amateur historian and prize winning photographer who lives in Margate, on the North Kent coast in the United Kingdom. Before retiring he worked both with and at Margate Museum, overseeing budgets on a number of historical projects.