Historian Toni Mount joins us today on her tour for the first book in her Sebastian Foxley Medieval Mystery series, The Colour of Poison. Toni discusses a few of our favourite things – the printing press, medieval books and Richard III, and introduces us to her new hero Sebastian Foxley. You’ve also got a chance to win a copy of Toni’s new book by commenting below.

The Printing Press by Toni Mount

By 1475 William Caxton had set up a new-fangled contraption in Bruges, in modern day Belgium, the printing press.

It was proving popular too. There was no denying it was much quicker and cheaper than a scribe, and there was even a rumour that Caxton was thinking of bringing his business to England soon. In The Colour of Poison, Sebastian Foxley and fellow members of his profession were involved in the creation books by hand, but who could read and write in medieval London?

By the fifteenth century, masters were beginning to expect their apprentices to be able to read, write and do a few sums. London wives were an asset to the business if they knew how to ‘construe the accounts’. This meant bookkeeping, adding up pounds, shillings and pence; stones, pounds (weight) and ounces; yards, feet and inches. Readers who can remember pre-decimalisation will know this isn’t simple, especially without a calculator. Doing the accounts would also mean being able to recognise words and write them down, but reading and writing were seen as two quite different skills. Far more people could read than could write. If you could read a letter sent to you and sign your name at the bottom of the reply, then you were literate. You could pay a scribe to write the reply, as Dame Ellen uses Sebastian in the novel, or have your secretary do it for you, if you were wealthy enough to employ one.

Books were big business in medieval England; they were expensive luxuries until the fifteenth century when prices became more reasonable, although never cheap. A book could be huge, lavishly illuminated and enclosed between jewelled and gilded covers, made for a wealthy abbey, or it could be a young school boy’s Latin grammar of a few pages, written on reused parchment (a palimpsest) and shared with his fellow pupils. This was important: books were meant to be shared, read aloud to an audience for pleasure or instruction, passed around to share the knowledge they contained and left as bequests in wills to the next generation. The idea of reading aloud was so ingrained that anyone who read silently to himself was thought to be a bit strange, but the idea was beginning to catch on in the late Middle Ages. Can you imagine a workshop full of copyists all reading aloud from a different book?

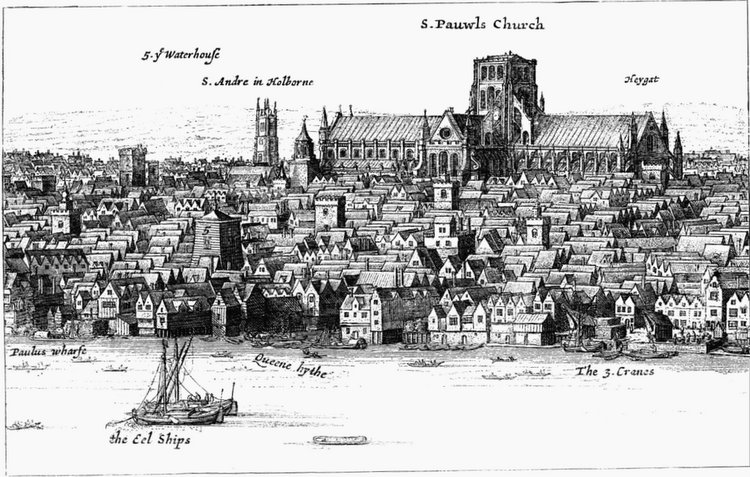

The London book trade centred round St Paul’s Cathedral. Stationers and book-sellers had their shops in Paternoster Row nearby, but they would often have book stalls in the cathedral itself, storing their supplies of parchment and paper in St Faith’s chapel in the undercroft. (This was still the stationers’ storage space in 1666, at the time of the Great Fire of London – one reason why St Paul’s burned so well.) Although the English book trade flourished, there were never enough books to meet the demands of an increasingly literate population. Even those who couldn’t read themselves might have a small volume or two in the hope a guest would read to them.

Kings and noblemen of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were beginning to build personal libraries. King Richard II was a patron of Geoffrey Chaucer. His cousin Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, had an impressive collection of books for the time. John Tiptoft, the Earl of Worcester, was another collector, although how much a library was a status symbol and how much an indication that a man loved reading is hard to tell.

The Stationers’ Company had been founded in 1403 in the reign of Henry IV when the text-writers (scribes) and the limners (painters and illuminators) combined forces. The company oversaw the production and construction of books and the buying and selling of them in London, but because there was always a shortage, books were also imported from Europe on a large scale, along with foreign scribes, book-binders and, later, printers. Londoners always resented foreigners (aliens, as they called them), and foreigners weren’t necessarily people from other countries, but simply folk who weren’t Londoners – Englishmen from outside the city. Quite a few scribes had come to London and Westminster from Lincolnshire in particular. Riots aimed at ridding the capital of these immigrants weren’t uncommon, so much so that Parliament regularly had to legislate for the protection of aliens. During the Revolt of the Commons (known today as the Peasants’ Revolt), back in 1381, apart from the hated authorities, aliens were among the first to come under attack. The Londoners’ complaint was always, then as now, that aliens were robbing them of their trade and work.

During the second half of the reign of Edward IV, from 1471-83, after his six-month exile in Bruges in Burgundy, the king built up a fabulous library of exquisite manuscripts, following the fashion of Louis de Gruuthuse, Lord of Bruges, who had taken him in as a house guest. Whether Edward read the books or just enjoyed admiring the glorious illuminations or simply wanted an impressive collection for its own sake, we’ll never know, but his youngest brother, Richard of Gloucester, was a true bibliophile. We know this because, although his library was small, the books are mostly quite plain, without lavish illumination, so he didn’t buy them to impress others or just to look at the pictures. Also, he inscribed his name neatly in each one, perhaps to make sure he got them back if he leant them out. He made or had a scribe put extra notes in the margins too, so we know he read them and none are pristine from lack of use. In fact, most of them were acquired second hand.

When Richard became King Richard III in 1483, his concern for books and literacy was made clear in his only Parliament, the matter being high on the agenda. To please his subjects, Richard legislated to limit the influx of alien craftsmen and the importation of goods from abroad with one exception: the book trade. He wanted more books to be cheaply available to everyone, so anyone could learn to read and share them and he knew the English book trade alone was insufficient for this. King Edward had allowed William Caxton to set up the first printing press in England at Westminster in 1476, but printing was further advanced in Germany and the Low Countries. These countries were happy to export books in English, Latin, French or any other language and King Richard made certain the customs duties on them were kept low, so more folk could afford to buy them.

Richard’s Act of Parliament of January 1484 removed any ‘impediment’ against the work or trade of ‘any writer, limner, binder or imprinter’ of ‘any manner [of] books written or imprinted’ by ‘any artificer or merchant stranger of what[ever] nation or country he be, selling by retail or otherwise’. That may sound as though the entire book business was fully covered, but there were loopholes: it didn’t include parchment-makers or stationers who supplied the imported paper. Things like inks and pigments were imported by grocers and apothecaries so weren’t exempt, and leather and cloth for bindings, thread for stitching pages together and glue, these were other necessities of the trade, which still had to be paid for with the full duties imposed. Maybe, if Richard had lived to have a second Parliament these matters would have been addressed.

We have one copy of The Colour of Poison to give away! To enter just leave a comment telling us why you want to read Toni’s new book. And be sure to check out all the stops on Toni’s book tour below.

The Colour of Poison by Toni Mount.

The first Sebastian Foxley Medieval Mystery by Toni Mount. The narrow, stinking streets of medieval London can sometimes be a dark place. Burglary, arson, kidnapping and murder are every-day events. The streets even echo with rumours of the mysterious art of alchemy being used to make gold for the King. Join Seb, a talented but crippled artist, as he is drawn into a web of lies to save his handsome brother from the hangman’s rope. Will he find an inner strength in these, the darkest of times, or will events outside his control overwhelm him? Only one thing is certain – if Seb can’t save his brother, nobody can.

Buy The Colour of Poison with Free Shipping Worldwide

Toni Mount earned her research Masters degree from the University of Kent in 2009 through study of a medieval medical manuscript held at the Wellcome Library in London. Recently she also completed a Diploma in Literature and Creative Writing with the Open University. Toni has published many non-fiction books, but always wanted to write a medieval thriller, and her first novel “The Colour of Poison” is the result.