There are few medieval kings who have caused centuries of continual debate. The first fictional depictions of “The Tyrant” Richard III came about in the sixteenth century, the first revisionist history of “Good King Richard” as early as the seventeenth century. His brief, twenty-two month reign is as notorious as it is elusive. King Richard III still baffles historians, his black legend infuriates his defenders and the memory of King Richard still inspires loyalty in his admirers. Five hundred years on it shows no signs of abating.

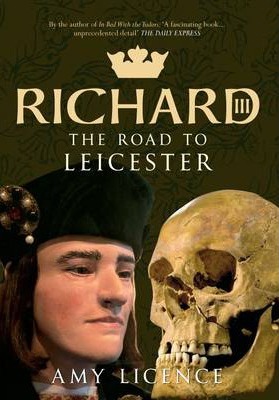

Richard III has seeped into popular culture, has been a constant media attraction since his remains were discovered last year, and those remains have sparked an increasingly heated battle over his final resting place. Historian Amy Licence joins us to discuss her new book Richard III: The Road to Leicester, which explores not only the life, but the afterlife of a King who has passed into myth and legend.

You have researched various members of the York family recently, what has it been like researching Richard III after his remains were discovered?

Very exciting! I was actually due to submit my book on Anne Neville three days before the announcement that they had found Richard ,and managed to get a few extra days extension, so I was glued to the screen listening to the announcement, taking notes and frantically writing. I think the discovery has made a huge impact, particularly bringing a lot of new interest in his life, from people who had been taught the old version of history at school, with the stereotypical villain Richard, from Shakespeare’s play. That’s why it is necessary for new books to set out the facts of his life as well as addressing the new information uncovered by the University of Leicester’s research.

You said that historians are increasingly attempting to “find a middle way when it comes to understanding his actions”. Is it difficult to find that balance and how important is it?

Of course lots of people have an opinion about Richard and reach very different conclusions about the controversies of his reign. That’s to be expected, as he has become a cultural phenomenon, pervading our art, drama, literature and general myth. It is very difficult to strip away everything we have absorbed about him, sometimes on a subconscious level, so finding the balance requires constant questioning of the use of language and imagery, the purpose and tone of sources, and the portrayals of the era in popular fiction. I do think it important to allow readers to make up their own minds, based on the facts, particularly in the light of so much fresh interest. Many are asking questions about his character, how he came to power and what happened to the Princes in the Tower. It is easier to write from a certain standpoint when it comes to Richard; the narratives of him as saint or sinner lend themselves to stronger stories and are far more colourful: but they are the extremes of a whole spectrum of possibilities. The effort to be impartial sometimes lends an unsatisfactory feel to a book, with the admission that much material has been lost to history and things like motivation can only be speculated upon. Some readers don’t like this: they want closed answers: yes he did or no he didn’t. In fact, we all want those answers, but until more evidence is uncovered, we can’t provide them. I’ve tried to look at a range of possibilities, consider the options and present as much as is known, so that people are informed. The conclusions they draw with that information is up to them.

Richard III was the ‘last medieval King of England’. How different was his upbringing compared to the upbringing of his great-nephews Arthur Tudor and Henry VIII?

Richard’s upbringing differed very much from that of his great-nephews, because he was not raised in the expectation of Kingship. Both Arthur and Henry were born to a reigning monarch but at the time of Richard’s birth in October 1452, he was a Duke’s son and would have had the education of an aristocrat, in reading secular and religious literature, learning to follow the elaborate social codes and undertaking a degree of chivalric training. He would have been raised in anticipation of being a great magnate, presiding over courts of law and taking an administrative role, either in England or France. His father, York, still supported Henry VI, and soon the Queen gave birth to a Prince. It looked like the Lancastrian dynasty was there to stay. However, things did begin to unravel and as Richard grew older, his experiences encompassing defeat, exile and the attainder and death of his father.

You discussed Richard III’s ‘literary afterlife’. We have travelled well beyond Shakespeare and we seem to either be presented with the romantic hero or the ultimate villain, do you think one can be as damaging as the other?

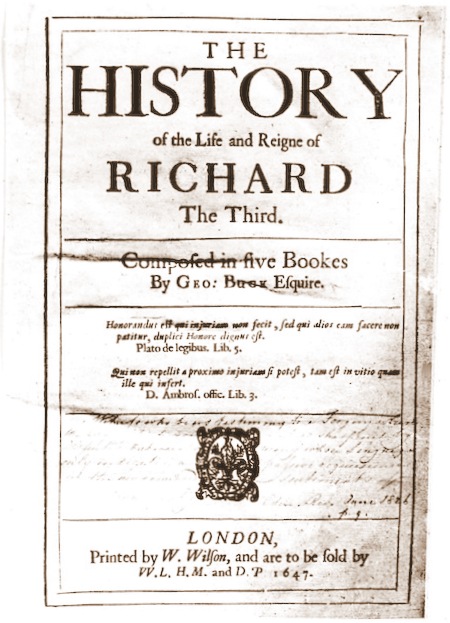

Extreme interpretations are usually unhelpful, as very few real people, if any, conform to such black and white interpretation. It is vital to remember we are dealing with an actual human being, a composite of many influences, who was subject to the interplay between free will and external pressure. None of us can know what it was like to be a medieval King, let alone one in the situation Richard found himself in 1483, so I think it is essential to keep an open mind. However, I do think it is essential that the extremes exist, partly in order to define the spectrum between them, but also to redress the years of anti-Ricardianism that followed his death. The reassessment of his reputation which began in the seventeenth century served a useful purpose in that it made people question certain assumptions. But it did serve its purpose back then and has laid the foundation for a more balanced approach today. It doesn’t really have a place in today’s historical analysis.

You also discussed Richard III’s ‘cultural afterlife’. He is a historical figure that seems to create a lot of division, and even a rivalry between Tudor enthusiasts and Richard III enthusiasts. Why do you think he inspires so much controversy?

It’s true, people do feel passionately about Richard. I think this has come partly out of a perceived injustice in the way he was treated in the past and a certain sympathy we have for the underdog. There is also the Bosworth issue; the juxtaposition of Richard as the embodiment of loyalty with the possibility that he was betrayed by those on whom he should have been able to rely: this evokes a good deal of indignation. The lack of contemporary sources has made him something of an enigma in relation to some of the biggest mysteries of English history and his brutal death on the battlefield cut short his life and reign. There is always a fascination with figures who die young, who seem in many ways to have held great promise but were unfulfilled. I suspect many people see Richard as a romantic figure who facilitates speculation and therefore, wish fulfilment. Then there have been so many persuasive films and novels, playing on our empathy and drawing sympathetic characters. When we look at historical figures through a romantic lens instead of aiming at an academic detachment, controversy is unavoidable.

Your next book Cecily Neville Mother of Kings is on Richard III’s mother, can you tell us a bit about it?

Your next book Cecily Neville Mother of Kings is on Richard III’s mother, can you tell us a bit about it?

When I initially started researching this book, drawn to understand the woman who had raised such an incredible family, I thought I had set myself an impossible task. I couldn’t see how I could fit together any sort of coherent narrative based on the slender facts I’d read about her in books about the times. However, as I trawled through all the contemporary documents, through the Parliamentary, Patent and Close Rolls, I began to turn up references to her properties, payments and movements that let me establish a framework. I was able to work out where she was at certain times and who was with her. I found things out about her family and early life, the first years of her marriage and her years as the mother of two kings. She had a large family, which was very important to her and I have explored the points where her life intersected with that of her siblings, children, grandchildren and descendants. But it has taken a lot of painstaking searching through primary sources, including a lot of contemporary satirical verses that I’ve not seen used by other historians when exploring the lives of the Yorks. Sarah Gristwood, author of Blood Sisters, was kind enough to read the book recently and said she was blown away by the amount of material I had uncovered.

What are you working on next?

I’m now working on a book about Henry VIII’s wives and mistresses, which will not just be rehashing the narrative of his life, but exploring the female experience. I’ll be drawing on the kinds of details that people liked in my first book In Bed with the Tudors; ritual, custom, women’s health, beliefs about sexuality and childbirth etc and setting these women in the wider context of gender politics of the day. It should be ready in time for Christmas, fingers crossed, but it’s going to be a long one.

With thanks to Amberley Publishing.

Visit Amy Licence at His Story Her Story

Visit Amy Licence at His Story Her Story

Amy Licence on Twitter @PrufrocksPeach

Amy Licence Facebook Fan Page In Bed With the Tudors

Writing about medieval and Tudor history, with a particular interest in women’s lives and experiences. I’m the author of four books and have also written for The Guardian, BBC History website, The New Statesman, The Huffington Post, The English Review and The London Magazine. I appeared in a BBC2 documentary “The Real White Queen and her Rivals” and have been interviewed numerous times live on radio. I’ve also been shortlisted twice for the Asham Award for women’s short fiction.

Richard III: The Road to Leicester by Amy Licence. Published by Amberley Publishing 2014

Richard III: The Road to Leicester by Amy Licence. Published by Amberley Publishing 2014

Buy Richard III: The Road to Leicester Free worldwide shipping at Book Depository (currently sold out on Amazon)

Following the dramatic announcement that Richard III’s body had been discovered, past controversies have been matched by fresh disputes. Why is Richard III England’s most controversial king? The question of his reburial has provoked national debate and protest, taking levels of interest in the medieval king to an unprecedented level. While Richard’s life remains able to polarise opinion, the truth probably lies somewhere between the maligned saint and the evil hunchback stereotypes. Why did he seize the throne? Did he murder the Princes in the Tower? Why have the location and details of his reburial sparked a parliamentary debate? This book will act as both an introduction to his life and reign and a commemoration to tie in with his reburial.