Dr Gillian Polack and Dr Katrin Kania join us on their book tour for The Middle Ages Unlocked : A Guide to Life in Medieval England, 1050-1300, a fascinating book brimming with everything you need to know about everyday life in the Middle Ages. From the government and the military, to religion, education, employment, architecture, food and drink, clothing and travel and so much more, The Middle Ages Unlocked offers something for every interest. Today Dr Katrin Kania shares her passion for tools and crafts with us, along with some wonderful photos.

I’ll make a confession for you, right at the start: I’m a tool nerd. I love tools. I enjoy researching them, seeing them in use, and buying them. Tools are a central thing for crafts, and thus a central thing for craft research, so I am a happy woman indeed: I get to research archaeological tools, reconstruct them, and use them.

Sometimes my tools are really simple. For instance, when I do band-weaving, I’ve been known to use any old thing for a shuttle: pieces of cardboard, pieces of wood, even bits of cloth. I’ve also woven by just taking the spool of silk thread that I was using as weft and passing that back and forth through the shed. Yes, I have one or two nice and beautiful wooden shuttles somewhere, but they are attached to some of my eternally-in-progress projects (maybe I should say “non-progress”) and so they’re all bound up. And I don’t need my shuttle to be beautiful or have a sharp straight edge because I beat the shed with my finger, or in some cases with another tool. When I do need a shuttle these days, I usually go for a very small and lightweight one cut from calf parchment. Why? They are cheap, easy to replace, and when I drop one it doesn’t weigh enough to distort the band by tugging on the weft thread as hard as a wooden shuttle would.

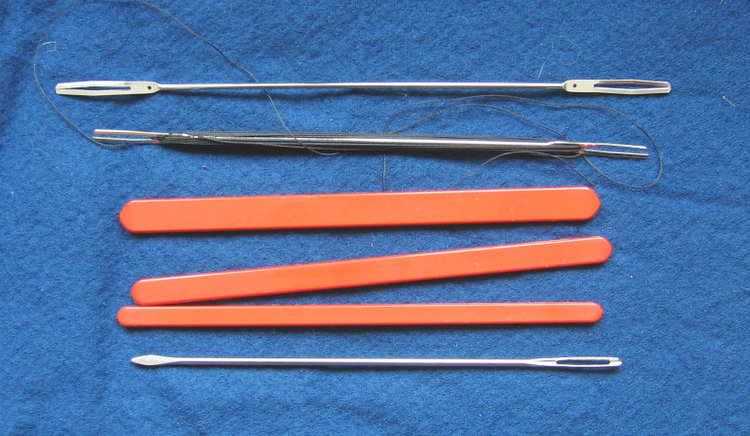

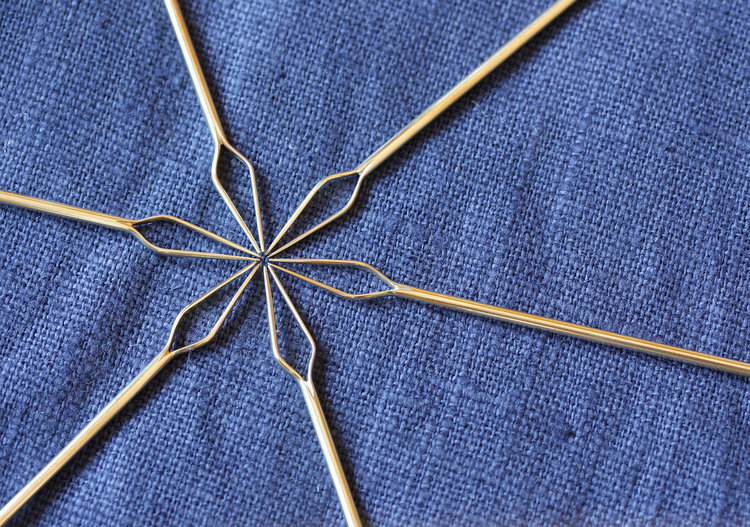

In other instances, though, I go for the best thing available. When I do filet netting, I work with thin silk threads, making small mesh nets, and my tool for this is a replica of a fourteenth century find from London. There’s nothing similar to it on the market today. Yes, you can buy something that is called a “netting needle set” from Prym, but comparing that to the medieval tool is like comparing a sledgehammer to a pair of tweezers.

I’m also the happy owner of a really good yarn winder, and of a spiffy reel modeled after Japanese reels. I used to work with the usual four-armed adjustable swift and was quite content with it… until I had pestered my friend and accomplice, Sabine the Dyer, to dye some really thin silk yarns with natural dyes for me. Sabine did the job, cursing all the while, and I joined her in the Song of Woe when I was trying to wind the yarn off onto spools. It just did not work at all with the normal swift, so I got my hands on a Schacht Goko, which does get the job done. (There’s still some cursing left in the job, but now it works.)

So, for me, sometimes the technique determines the tool. Sometimes the materials do. Sometimes it’s a question of what tool I started the job with, as I’ve gotten used to one thing and changing it would break my work flow.

Getting used to tools, that’s another really interesting aspect. When you use one specific tool a lot, you get attached to it. You know exactly how it fits in your hand, how to wield it, when to adjust or sharpen something. You know how it interacts with different materials, or different angles. It becomes an extension of your hands, even of your self. When that tool is mislaid, yes, you could do with another – but it’s not the same, and you feel it.

Medieval tools show much the same variety. There are very simple tools and gadgets and very high-end ones (like the netting needle). On some tools, you can see the traces of a lifetime of use; others (such as crucibles) have a limited life-span and get discarded once they wear out. When tools are recovered from archaeological digs, they are often corroded from lying in the soil for a few hundred years and it can be hard to see traces of use-wear on them. We do have some evidence, though: highly polished stones that were probably used to burnish something; bone weaving tablets with grooves worked into the material around the holes; punches with burred heads, indicating they’ve been hit with a hammer and more than once.

For an archaeologist, these traces of tool wear are a wonderful help for crafts research. You can see how far some tools were worn down, and sometimes how they were used, or get an indication of the materials they might have been used on. Put this research together with the analysis of tool marks on finished and semi-finished objects, and you have so much to explore and learn. It also provides the basis to venture into some experiential archaeology (that’s when you use tool replicas and appropriate materials and techniques to make things or just fool around) and experimental archaeology (that’s when you look for answers on a specific question with help of an experimental, reproduceable set-up designed just to answer that question).

Apart from all of this, however, there’s something more to seeing old tools for me. It connects me to so many other craftspeople that came before me. People who may have loved their craft or hated it (or both, at times). People who were utterly brilliant at it and people who muddled along. People who tried out new tools, new materials, new techniques and people who stuck with the old-fashioned methods because obviously that is the only way you ever do it. People who always got the best tools and people who muddled along with some rickety improvised thingummy that barely did the trick, but at least they knew how it worked.

And here I am, today, trying to gain experience in crafts almost forgotten these days, sometimes muddling along and sometimes feeling quite competent. My tools? Some barely do their job, but I’ve not gotten around to replacing them. Some are top-notch. Some are in-between. Looking back at the medieval tool finds and what the craftspeople did with them, I think I’m in good company.

Pictures ©Katrin Kania. Do not reproduce.

The Middle Ages Unlocked : A Guide to Life in Medieval England, 1050-1300 by Gillian Polack and Katrin Kania, foreword by Elizabeth Chadwick, published by Amberley Publishing 2015.

To our modern minds, the Middle Ages seem to mix the well-known and familiar with wildly alien concepts and circumstances. Unlocking the Middle Ages provides an introduction to this complex and dynamic period in England. Exploring a wide range of topics from law, religion and education to landscape, art and magic, between the eleventh and early fourteenth century, the structures, institutions and circumstances that form the basis for daily life and society are made accessible. Drawing on their expertise in history and archaeology, Dr Gillian Polack and Dr Katrin Kania look at the tangible aspects of daily life, ranging from the raw materials used for crafts, clothing and jewellery to housing and food, to bring the Middle Ages to life. Unlocking the Middle Ages dispels modern assumptions about this period, revealing the complex tapestry of medieval England, its institutions and the people who lived there.

Click here to buy The Middle Ages Unlocked with Free Worldwide Shipping

Click here to buy The Middle Ages Unlocked for Kindle

Dr Katrin Kania is a freelance textile archaeologist and teacher as well as a published academic who writes in both German and English. She specialises in reconstructing historical garments and offering tools, materials and instructions for historical textile techniques. Find her website at www.pallia.net and her blog at togs-from-bogs.blogspot.com. She also tweets under @katrinkania.

Dr Gillian Polack is a novelist, editor and medieval historian as well as a lecturer. She has been published in both the academic world and the world of historical fiction. Her most recent novels include Langue[dot]doc 1305 and The Time of the Ghosts (both Satalyte publishing). Find her webpage at www.gillianpolack.com and her tweets under @GillianPolack.