It would be tempting to suggest that George Boleyn has been the victim of a certain amount of stereotyping over the centuries. But then one would have to also suggest that we have a clear picture of George Boleyn. That what we have seen of George in the pages of history has been more than glimpses, that what has survived of George Boleyn is more than fragmentary. That somehow his words and deeds have resonated through history and become ingrained in popular culture, and thus we could fit George into one of those neat little stereotypes we reserve for historical figures.

It would be tempting to suggest that George Boleyn has been the victim of a certain amount of stereotyping over the centuries. But then one would have to also suggest that we have a clear picture of George Boleyn. That what we have seen of George in the pages of history has been more than glimpses, that what has survived of George Boleyn is more than fragmentary. That somehow his words and deeds have resonated through history and become ingrained in popular culture, and thus we could fit George into one of those neat little stereotypes we reserve for historical figures.

The fact is much of what we have seen of George Boleyn until now is shaped by fiction. Perhaps he has really been the victim of various fictional tropes, the tragic victim, the arrogant courtier, the uncaring husband. Perhaps in the ongoing battle to exonerate his sister, Queen Anne Boleyn, historians relegate the seemingly unassuming figure of George Boleyn to the sidelines. But did more of George Boleyn survive than we realise?

It only takes the dedication of one person, or in our case two, to explore the lives of shadowy historical figures and bring them to life. Now years of exhaustive research have culminated into this vivid, encompassing and thoroughly convincing portrait of a man that history has forgotten. Clare Cherry and Claire Ridgway join us today to discuss their new biography George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat.

You two met and began corresponding through Claire’s Anne Boleyn Files website, how did your George Boleyn project come about?

Clare Cherry– I started researching George towards the end of 2006/beginning of 2007, because I found him quite intriguing. At first it started for my own pleasure and I had no intentions of that research turning into a book. As I did more research, however, I became more and more interested in the man, and more and more concerned about how he was portrayed in fiction and how much he was unfairly demonised. The project became a book length manuscript which I sent to Claire early in 2010. She liked it, but at that stage it needed work doing to it and properly editing. Claire added to it from her own research and it went from there.

What was your perception of George Boleyn before you started researching him?

Claire Ridgway– I figured that he’d probably been maligned as much as Anne Boleyn had and that the “picture” I had of him in my head was probably way off base even though it wasn’t based solely on fictional portrayals. Through my research into Anne, I knew that George was a diplomat and had a career in his own right, but I didn’t realise just how important he’d been and how many embassies he’d undertaken.

Can you tell us about discovering Edmond Bapst’s biography of George?

Can you tell us about discovering Edmond Bapst’s biography of George?

Clare Cherry– I found a reference to Bapst in a biography of Anne by Marie Bruce. It’s the first time I had ever come across it. I bought the book, which was a very old copy that was almost falling apart and left brown stains on everything it touched, including a table cloth and my hands! I was mortified to discover it was in French and there was no English translation. As I don’t speak French it took me about three months trying to translate it as best I could. When Claire became involved in the project she got it professionally translated, which was a blessing.

George’s successful career is often attributed to Henry VIII’s relationships with George’s sisters. Can you tell us about George’s early career at court?

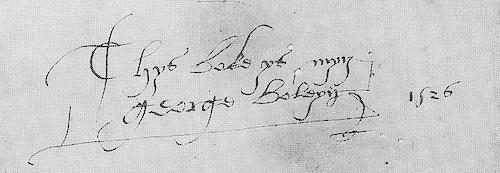

Claire Ridgway – The first record of George Boleyn attending the royal court of Henry VIII is as a child during the Christmas festivities of 1514-15. In around 1516 he was appointed as one of the King’s pages. The earliest extant record of George as an adult at court is in April 1522, when he was about 18, when he and his father received a joint grant of various offices that had belonged to the executed Duke of Buckingham. It is probable that he took a permanent position at court around this time. George lost his position as page in January 1526, following Cardinal Wolsey’s Eltham Ordinance, but was made the King’s cupbearer as compensation. As cupbearer, he would have served the King at all state occasions and would have travelled around with the King, as he did in 1528 when the King and Queen fled to Waltham Abbey to try and escape the sweating sickness.

In 1528, George was appointed an Esquire of the Body, Master of the Buckhounds and keeper of the Palace of Beaulieu, and he was knighted in 1529 and granted several other offices. He was appointed as ambassador to France in October 1529 and carried out his first embassy.

You’ve examined the marriage of George and Jane Boleyn and Jane’s alleged role in the trial in depth. Why do you think their marriage has always been depicted as unhappy, and rather than this myth diminishing over time it has in fact become even more sordid?

Clare Cherry– I think the beginnings of the belief that the marriage was unhappy stem from Jane being thought to be responsible for bringing Anne and George down on false allegations of incest. Obviously if that were true than she would have to have disliked her husband enough to bring about his death, which leads to the inevitable conclusion that the marriage was unhappy. However, there is no contemporary evidence to prove Jane to have given evidence save for telling Cromwell that Anne had confided in her about Henry’s sexual problems. If you take that away then there is no proof that the marriage was unhappy. George is accused of being a womaniser by Cavendish, but most courtiers had mistresses, including the King. That in itself doesn’t necessarily mean the marriage was particularly unhappy. But then fiction writers took the ‘unhappy’ marriage and ran with it. An evil vindictive Jane, and a promiscuous George makes good reading, and so the myth has been repeated over and over again, and with each retelling the marriage becomes more and more unhappy until we have George raping his wife and being cruel too her. There is no evidence to support any of that but the depiction of Jane and George has become entrenched by repetition, as has the portrayal of an unhappy marriage.

Can you tell us more about George’s role in the beginnings of the English reformation?

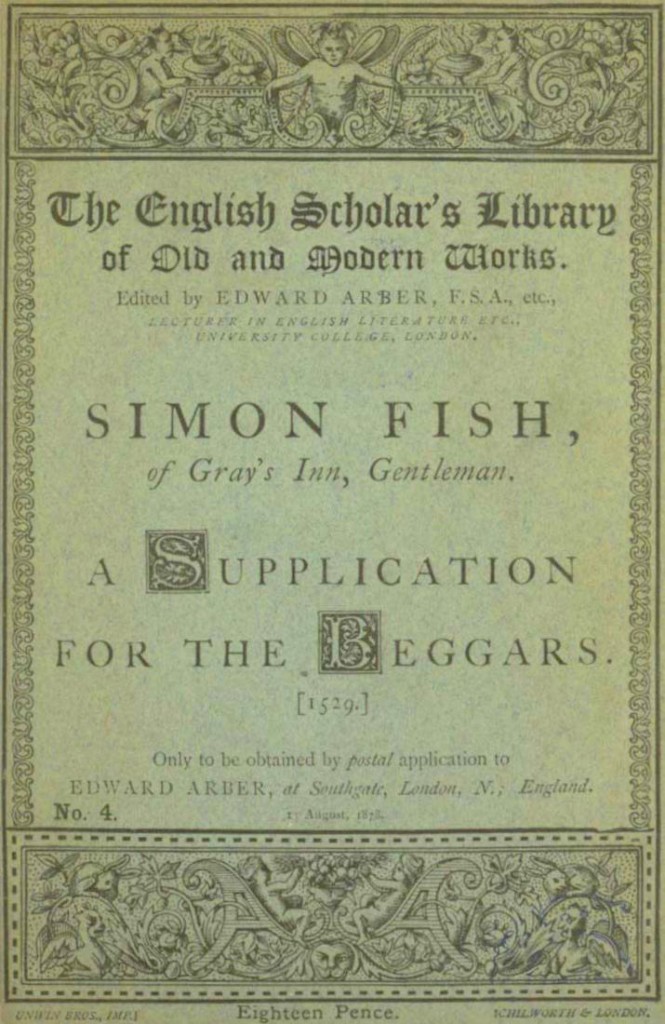

Claire Ridgway– In his scaffold speech, George described himself as “a setter forth of the word of God” and Clare and I believe that his influence in the religious changes which swept England in the mid-1530s has been largely overlooked. He may not have had Anne’s influence, but he did use his position to promote his religious views. According to Simon Fish’s wife, it was George who persuaded Anne to give Fish’s pamphlet, the evangelical and revolutionary A Supplication for the Beggars, to the King, who was impressed with the pamphlet and had a personal meeting with Fish some two years later.

George, Anne and their father financially supported Nicholas Heath, who became one of Thomas Cranmer’s evangelical circle, at Cambridge University. Heath became the rector of St Peter’s Church, Hever, the Boleyn family church, in 1531 and he worked closely with Archbishop Cranmer and Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham, in overseeing the Bible translations which became the 1539 Great Bible.

The manuscripts George prepared for Anne, which were based on texts by French reformer Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, are evidence of the religious ideas which were influencing the siblings. The recurrent theme of the texts was the doctrine of justification by faith, which is often seen as a Lutheran doctrine but which Lefèvre was writing about years before Martin Luther. The imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, complained that George insisted on entering into religious debate whenever he was being entertained by him, and described his discussions as “Lutheran”, so George obviously enjoyed ‘evangelising’.

The Reformation Parliament of 1529-1536 was responsible for passing the main pieces of legislation which led to the English Reformation and although George was not called to Parliament until February 1533, he maintained a prominent role in the Reformation from 1530 until his death and his attendance was highly impressive.

We know that Anne and George Boleyn were close, but what was George’s relationship with his brother-in-law Henry VIII like?

We know that Anne and George Boleyn were close, but what was George’s relationship with his brother-in-law Henry VIII like?

Clare Cherry – George was introduced to Henry as a 10 year old and soon afterwards became his page. By 1525 he was Henry’s personal page, losing his position in the Eltham Ordinances. He later became Gentleman of the Privy Chamber in 1529. I think Henry liked George in his own right, and wouldn’t have suffered his constant company unless he did. The Privy Purse Expenses show money being paid out to George for a variety of sports and pastimes, showing George spent a great deal of time with the King. I also think Henry appreciated George’s talents as a politician and diplomat. This is proved by the positions of trust George was given at such a young age. Henry liked and respected him.

How was George perceived by his peers towards the end of his life?

Claire Ridgway – Thomas Wyatt, in his poetry on the executions, wrote:

“Some say, ‘Rochford haddest thou not been so proud

For thou great wit each man would thee bemoan,

Since it is so, many cry aloud

It is a great loss that thou art dead and gone.”

So perhaps he was seen as proud and arrogant by some, but still “many” mourned his death so he must have been popular and well-liked. There is no evidence that he had become unpopular before his fall.

Was the any chance George could have escaped being implicated along with his sister Anne, or did his close relationship with her pose too much of a threat?

Clare Cherry – I think, once Henry thought George and Anne were talking about him in a disrespectful manner, that George had no hope of surviving. I don’t accept that Henry genuinely believed the incest allegation. I think it was derived at out of spite and malice; Henry’s not Cromwell’s. The incest charge was so implausible that I find it difficult to accept it derived from Cromwell. It was that charge which caused the most raised eyebrows and disbelief, and if that wasn’t true then it cast doubt on the other convictions. I think it was most definitely Henry’s work, so no, I don’t think George had any hope of survival.

Is it fair or even realistic to expect that Thomas and Elizabeth Boleyn could have tried to intervene on their children’s behalf?

Claire Ridgway– We know that Sir Francis Weston’s family fought for Weston’s release, offering money and getting the French ambassadors, Jean, Sieur de Dinteville, and Antoine de Castelnau, Bishop of Tarbes, to intercede on their behalf, so the Boleyns could have tried to intervene. However, we don’t know for sure that they didn’t try. Documents which had belonged to Thomas Cromwell were mutilated and/or destroyed in the Ashburnam House fire of 1731, so perhaps a letter from Thomas Boleyn was destroyed then – we don’t know. I think they would have known that there was no hope anyway, they’d seen it all before.

Can you tell us what you think George’s conduct during his trial tells us about his character?

Clare Cherry– George faced his trial with bravery and composure, despite the fact he knew he was going to die. Likewise, he faced death with equal bravery and composure. He gave a lengthy and impassioned speech in support of his religious views, and I think he was admired for that. He acted in accordance with protocol, and did it with aplomb. I think his downfall tells us a great deal about the character of a man who was only around 32 at the time, and was being put to death for a crime most people knew he hadn’t committed.

Why was George’s execution speech so important and what do you think it tells us about life in Henry VIII’s court?

Claire Ridgway– In his scaffold speech, George warned everyone present to use him as an example, especially his fellow courtiers. He warned them “not to trust in the vanity of the world, and especially in the flatterings of the Court, and the favour and treacheries of Fortune”, which he said raised men up only to “dash them again upon the ground”. George knew that there were others at court who were riding high in the King’s favour at the moment but who would also come to a sticky end. One day the King would love you, the next you’d be in fear of your life – just look at the examples of Cardinal Wolsey, Thomas More, Nicholas Carew, the Seymours…

As we write in our book, “His positions of favour and power had resulted in sycophantic flattery by friends and enemies alike, and he had swallowed it whole. He had waltzed around the court with an air of arrogance in the certainty of his position, and because of his confidence in himself and the respect in which he was held. Yet those same people who had fawned over him were here now, watching him die. It was all false, and only at the very end did he realise this.”

The King’s favour was fleeting, that was one of George’s messages that day.

What do you hope readers will take away with them from your book?

Clare Cherry– I hope readers will see George in a different light to how he is depicted in fiction. I hope he will be seen as a competent courtier, diplomat and politician, who was charming, witty and intelligent. I hope people will come away with a new-found respect for him.

W

Visit the official George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat website at georgeboleyn.com

To win a copy of George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat leave a comment below before midnight Friday 30th of May.

You have eleven chances to win a copy of George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat over eleven days on the George Boleyn Virtual Book Tour. Here’s the schedule.

Monday 26 May – Anne Boleyn: From Queen to History where we share what the sources tell us about George Boleyn the man.

Wednesday 28 May – The Tudor Tutor, where we share our thoughts on George’s relationship with Henry VIII.

Thursday 29 May – Susan Higginbotham’s History Refreshed blog, where we talk about George’s position as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports.

Friday 30 May – QueenAnneBoleyn.com, where we’re interviewed about George and our book by Beth von Staats.

Monday 2 June – The Lady Jane Grey Reference Guide, where we discuss how we came to be writing this book together.

Tuesday 3 June – On the Tudor Trail, to answer 20 questions.

Wednesday 4 June – The Tudor Cafe for a Q&A session.

Thursday 5 June – TudorHistory.org, where we share our favourite primary sources.

Friday 6 June – The Tudor Roses, where we share an extract from our book about George’s love of falconry.

Saturday 7 June – Gareth Russell’s Confessions of a Ci-devant, where we look at George Boleyn’s scaffold speech.

Clare Cherry lives in Hampshire with her partner David. She works as a solicitor in Dorset, but has a passion for Tudor history and began researching the life of George Boleyn in 2006. She started corresponding with Claire Ridgway in late 2009, after meeting through The Anne Boleyn Files website, and the two Tudor enthusiasts became firm friends. Clare divides her time between the legal profession and researching Tudor history. Clare has written guest articles on George Boleyn for The Anne Boleyn Files, Nerdalicious.com.au, and author Susan Bordo’s The Creation of Anne Boleyn website.

Claire Ridgway is the author of the best-selling books ON THIS DAY IN TUDOR HISTORY, THE FALL OF ANNE BOLEYN: A COUNTDOWN, THE ANNE BOLEYN COLLECTION, and THE ANNE BOLEYN COLLECTION II, as well as INTERVIEWS WITH INDIE AUTHORS: TOP TIPS FROM SUCCESSFUL SELF-PUBLISHED AUTHORS. Claire was also involved in the English translation and editing of Edmond Bapst’s 19th century French biography of George Boleyn and Henry Howard, now available as TWO GENTLEMAN POETS AT THE COURT OF HENRY VIII.

Claire worked in education and freelance writing before creating The Anne Boleyn Files history website and becoming a full-time history researcher, blogger and author. The Anne Boleyn Files is known for its historical accuracy and Claire’s mission to get to the truth behind Anne Boleyn’s story. Her writing is easy-to-read and conversational, and readers often comment on how reading Claire’s books is like having a coffee with her and chatting about history.

George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat by Clare Cherry and Claire Ridgway, 2014

George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat by Clare Cherry and Claire Ridgway, 2014

Buy George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat

George Boleyn has gone down in history as being the brother of the ill-fated Queen Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII, and for being executed for treason, after being found guilty of incest and of conspiring to kill the King.

This biography allows George to step out of the shadows and brings him to life as a court poet, royal favourite, keen sportsman, talented diplomat and loyal brother. Clare Cherry and Claire Ridgway chart his life from his spectacular rise in the 1520s to his dramatic fall and tragic end in 1536.