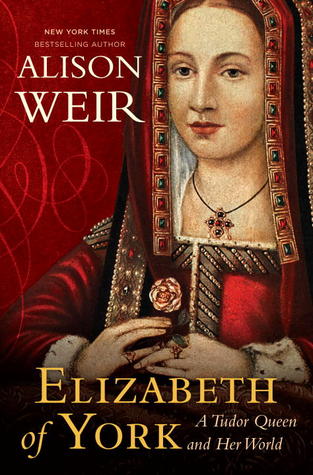

Queen Elizabeth of York is famous for her beauty and her kind, gentle nature. The tragedy and hardships she overcame to become Queen are often overlooked, her strength of character diminished. Elizabeth has become the captive princess who awaited the menfolk to determine her future, the long-suffering Queen kept powerless by her husband. Historian Alison Weir’s new biography Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen re-examines her life, showing us the woman who may have intrigued to put her betrothed on the throne and topple her uncle from power, in contrast to the image of a passive princess that has been created over the centuries.

Queen Elizabeth of York is famous for her beauty and her kind, gentle nature. The tragedy and hardships she overcame to become Queen are often overlooked, her strength of character diminished. Elizabeth has become the captive princess who awaited the menfolk to determine her future, the long-suffering Queen kept powerless by her husband. Historian Alison Weir’s new biography Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen re-examines her life, showing us the woman who may have intrigued to put her betrothed on the throne and topple her uncle from power, in contrast to the image of a passive princess that has been created over the centuries.

Alison Weir joined us to discuss just how instrumental Elizabeth of York was in shaping her own destiny.

You have written books on the Princes in the Tower and the Wars of the Roses. What was it like returning to these subjects and looking at the events through Elizabeth of York’s eyes?

It’s fascinating to view them from another person’s perspective, especially that of a woman who had very little power yet was integral to the high power politics of her day. Most of my research on her was done before I wrote those earlier books, so my task was to update it and re-evaluate it in the light of more recent work on the period. That meant re-examining the mystery of the fate of Elizabeth’s brothers, the Princes in the Tower, because it had such a crucial bearing on her life.

The attitudes towards Richard III have evolved a great deal over the years, in particular he has been depicted as quite a romantic hero in fiction over the last few decades and lately we have seen his relationship with Elizabeth of York depicted as a sexual one. Do you think fiction authors are sensationalising the relationship between uncle and niece?

Richard III seems to have a strange charisma for many, despite the weight of evidence against him. I understand that, but it does concern me that some people get very emotional about him. After all, he died nearly 550 years ago, and his character is something of an enigma. So much that is written about him is subjective. The last thing I would see him as is a romantic hero! It would be less surprising if people got worked up about the dreadful fate, let alone murder, of the two dispossessed princes, whom Richard disinherited on dubious grounds and imprisoned. But I put my hand up to depicting Richard’s relationship with Elizabeth as a sexual one, in my book The Princes in the Tower (1992). I don’t take that view nowadays. But when I was researching that book, A.N. Kincaid’s new translation (or rather, reconstruction) of the controversial letter on which that theory rests had not long been published, and for the first time historians could read how Elizabeth declared that she was the King’s in heart, in thought, in body and in all. The words ‘in body’ had never appeared in previous versions of the letter, so it looked as if they had been censored. I was not the only historian to interpret them as referring to a sexual relationship. But on reflection I think they mean something else entirely. I haven’t read any fictional treatment of the relationship between Richard and Elizabeth, but I’ve read plenty that portray Richard’s marriage to Anne Neville as a love story – for which there is no evidence – so it would not surprise me if his relations with his niece have been sensationalised. For which I fear I must bear some of the blame!

When Richard III publicly denied any intention to marry his niece and began to arrange a Portuguese alliance, offering Elizabeth’s hand in marriage, you note that this would “leave her family without a friend in high places”. Do you think that despite the fact that Richard III had overthrown her family and bastardised her that Elizabeth still saw herself as the rightful heir to throne?

Yes, all the evidence points to that. The letter cited above, and the poem describing Elizabeth’s efforts to raise men for Henry Tudor – neither of which should be lightly dismissed – both show her manoeuvring to become queen of England, which, in the eyes of many Yorkist legitimists, she was.

You’ve taken a close look at Elizabeth’s role in the events before Bosworth and the possibility that she enlisted Lord Stanley, her future father-in-law, to aid her, noting that a marriage to Henry Tudor seemed “the best way to satisfy her ambition, restore her rights and safe-guard her kinsfolk”. Do you think Elizabeth had a more active role in trying to determine her own fate than we have been led to believe?

Yes, I do. I place some credence on the sources cited above, which show Elizabeth actively working behind the scenes to achieve her ambition. Internal evidence in both the letter and the poem indicates that both have factual substance, although there is a degree of dramatic licence and exaggeration in the poem.

You called the marriage between Elizabeth and Henry VII the “most successful and stable marriage made by any of the Tudors.” It was clearly a loving marriage and a very popular one, and much of Henry’s bad reputation developed after her death, do you think this is largely to do with Elizabeth’s nature and that she was a good influence on him, and in many ways an ideal wife and Queen Consort?

I would say that Elizabeth was in every sense an ideal wife and consort. She met every contemporary expectation. The sources show that she was a loving, kind and gentle woman, and as such she must have been a force for good in Henry’s life. That she had influence with him is evidenced by the numerous gifts to her from powerful persons who clearly thought that her patronage was worth having. And the fact that Henry’s character degenerated after her death speaks volumes.

One thing that seems to frustrate historians and readers alike is the fact that Elizabeth of York never made a public statement on the identity of Perkin Warbeck, the pretender who was posing as her dead brother Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York. Why do you think she stayed silent on the matter?

Elizabeth never publicly involved herself in politics. Whatever she did say was uttered in private, and it is hard to imagine her suggesting to a beleaguered Henry VII that Warbeck might really be her brother, even if she did entertain that suspicion. To have done so might have shattered the trust that the couple had built up over the years, and cast doubts on her loyalty. By the time Elizabeth set eyes on Warbeck, he had confessed to not being her brother, so there was no need for her to make any pronouncement on that.

You have made a fascinating connection between Elizabeth and Sir James Tyrell, the man who is said to have confessed to murdering her brothers, the Princes in the Tower, when Elizabeth made a visit to the Tower of London. You also noted a visit to Wales on her final progress and you surmise she may have still been looking for answers on the fate of her younger brothers. Do you think that Elizabeth truly had not known what happened to her brothers and that it may still have been haunting her?

I think she probably knew as much as Henry Tudor, Buckingham and Margaret Beaufort – that Richard III had intended to have the Princes killed (as he may well have confided to Buckingham, who promptly deserted him), and assumed, along with them, that he had done so. But the uncertainty, coupled with stories that the Princes survived, which emerged in Henry VII’s reign, and the claim of Warbeck, probably led her to wonder. Speculation in Elizabeth’s lifetime focused more on how they had died rather than on who killed them, because most people believed that Richard III had been responsible. The exact nature of their fate may have been what haunted her. If she did hear from Tyrell that he had arranged their murder, she might have sought corroboration elsewhere, possibly at Raglan. But we are way into the realms of speculation here.

Do you think Elizabeth of York was integral to the success of the Tudor dynasty?

Yes, certainly. Support for Henry Tudor was largely based on his consolidating his claim, and conquest, by marrying her, and her popularity helped to lay the bedrock of the dynasty’s success. Henry VII may not have acknowledged the dynastic debt he owed to her, but Henry VIII did, recognising that his claim to the crown rested largely on his descent from his mother.

Visit Alison’s official website alisonweir.org.uk and her historical tours website alisonweirtours.com

Visit Alison’s official website alisonweir.org.uk and her historical tours website alisonweirtours.com

Alison Weir on Twitter @AlisonWeirTours

Alison Weir Facebook Fan Page

Alison Weir is the top-selling female historian (and the fifth best-selling historian overall) in the United Kingdom, and has sold over 2.3 million books worldwide. Born in London, she was educated at the City of London School. Later, she trained as a teacher, with history as her main subject. But her great love of history had been born some years earlier, after reading her first adult novel at the age of fourteen. After that, she took up history as a hobby. Alison had a career in the Civil Service before her first book, Britain`s Royal Families, came out in 1989. She has since written fourteen other history books, including The Six Wives of Henry VIII, The Princes in the Tower, Lancaster and York, Children of England, Elizabeth the Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry VIII: King and Court, Mary Queen of Scots and the Murder of Lord Darnley, Isabella She-Wolf of France, Katherine Swynford, The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn and Mary Boleyn:“The Great and Infamous Whore”. Alison has also published four historical novels, Innocent Traitor, The Lady Elizabeth, The Captive Queen and her latest book, A Dangerous Inheritance. Her latest biography is Elizabeth of York (November 2013). Until 1997 she ran her own school for children with special needs, and has a special commitment to promoting adult literacy. In 2010 she published a short book, Traitors of the Tower, for the Quick Reads series for emergent adult readers. In 2012 she founded her own historical tours company, Alison Weir Tours Ltd. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences and an Honorary Life Patron of Historic Royal Palaces, and is married with two adult children.

Elizabeth of York: A Tudor Queen and Her World published by Ballantine Books (US edition) available now.

Buy Elizabeth of York: A Tudor Queen and Her World

Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen published by Jonathan Cape (UK)

Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen published by Jonathan Cape (UK)

Buy Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen