The rise of the Tudors is the stuff of myth. Edward IV has suddenly and tragically died, and his brother has seized the throne and imprisoned his nephews. Margaret Beaufort is attainted for treason against her new King, Richard III, and is under house arrest. Her son, the heir of Lancaster, is abroad, exiled, separated from his mother most of his young life. The Dowager Queen Elizabeth Woodville is trapped in sanctuary with her five daughters, her eldest the Princess Elizabeth of York, now the rightful heir to the throne in the eyes of many after the disappearance of her brothers. Two powerless women make a pact. They gamble with their lives, and that of their children. Henry Tudor will come from over the sea and claim his inheritance, he will take the throne and his princess for a bride.

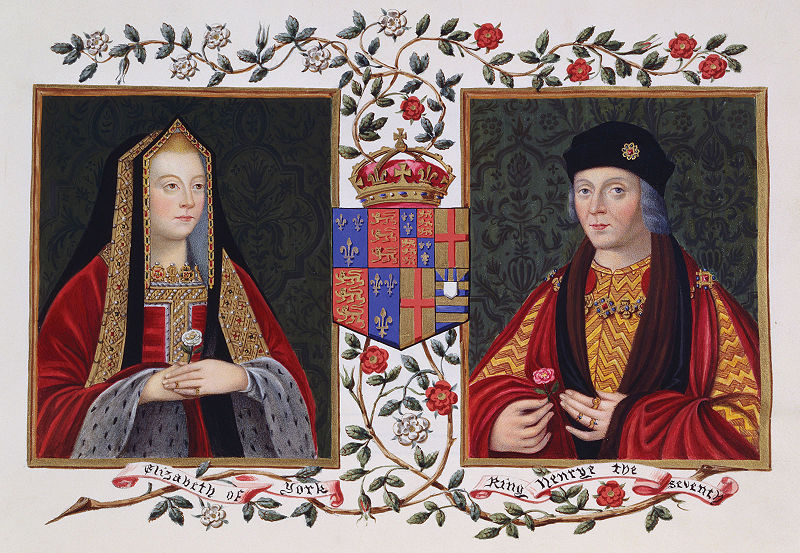

In 1483 Margaret purchased a manuscript of the thirteenth-century French romance Blanchardin and Eglantine ‘the noble acts and feats of war by a noble and victorious prince named Blanchardin… for the love of a noble princess called Eglantine…and of the great adventures, laborous anguishes and many other great diseases of them both before they might attain for to come to the conclusion of their desired love’ from William Caxton 1 Was she thinking of her future daughter-in-law, the beautiful Princess of York and her son? It would be many months before Henry Tudor would reach England. He came with an army made up largely of mercenaries, he was about to fight his first ever battle against a brilliant military commander with an army twice the size of his. But the last York brother fell in battle and against all odds an unknown Welshman would take the throne of England and rescue his beautiful princess. Henry VII has descended from the ancient Kings of Britain. He has won the throne against insurmountable obstacles, surely he must have been chosen by God. The marriage between Henry VII and Elizabeth of York would unite the House of Lancaster and York and heal the wounds of a nation torn apart by faction wars for almost three decades.

A Fairytale Marriage

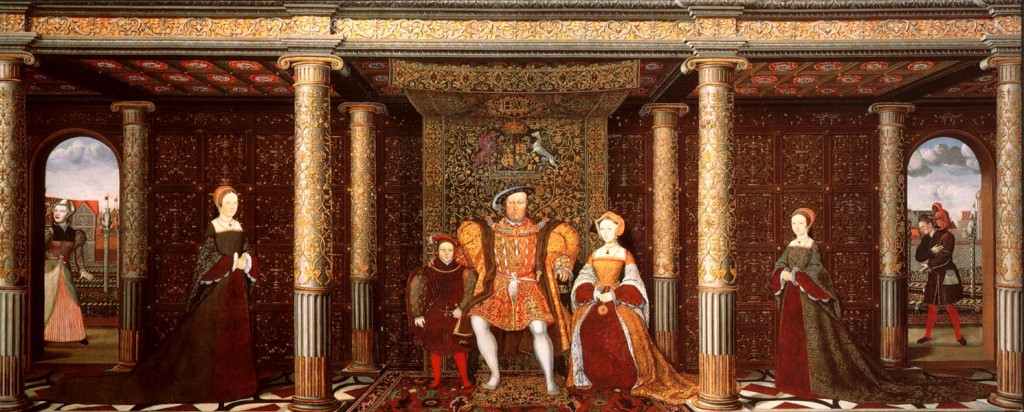

A young Prince Henry must have been regaled with these sorts of romantic tales of his brave father and his beautiful mother. Perhaps he was told tales of his courageous grandmothers. He certainly would have heard stories of his grandfather’s battles during the Wars of the Roses. But Henry’s childhood would be much easier. Henry VII, who had spent most of his life a penniless exile with only his uncle Jasper Tudor by his side, was now blessed with a relatively peaceful nation, and the perfect wife. Not only was Elizabeth of York beautiful, gracious and kind, she was intelligent and cultured and the couple shared many interests. Also, of the utmost importance, she gave Henry VII a family. Young Henry was only the spare heir, his older brother Prince Arthur was sent to Wales to establish his own household and receive his education, and Henry stayed at the family home of Eltham Palace with his sisters. Henry VII and Elizabeth had created a lavish court in the Burgundian style, no doubt modelled on the glamorous court of Elizabeth’s famously good-looking and charismatic parents, Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. Henry would see his parents enjoying music and entertainment together, gaming and hunting, they shared a love of books, learning and theology. Henry himself would grow to love the same things. The Tudors would entertain lavishly on important occasions, Twelfth Night, Christmas and New Years with performers generously rewarded by the treasurer of the King’s chamber. Every summer solstice bonfires would burn through the few hours of darkness, with bold young men leaping over them and often receiving a scorching for their daring. 2

The middle-ages had ended with the Battle of Bosworth. The Tudors would put down the swords and pick up the books.

A Family Home

The reign of King Henry VII was not all smooth-sailing of course, he dealt with several rebellions during the early years of his reign that put his family in danger. During the Cornish rebellion of 1497 Queen Elizabeth would flee to her mother-in-law’s house with her small son, and they would then spend five days in the Tower of London with the rebels within earshot. At age five Henry was perhaps a little too young to understand the gravity of the situation, however, and may have thought it a bit of an adventure with his beloved mother.

Elizabeth was a hands-on mother, like her own mother had been. She was the product of a love-match, her father famously outraging the nobility by taking a beautiful commoner for his wife. Her parents were devoted to each other, despite her father’s many mistresses and Elizabeth was raised in a close and loving family. Young Henry would grow up in the same environment. Elizabeth may have lived the luxurious life of a Queen, but she still enjoyed domestic pursuits. While she employed a French embroiderer, Robinet, she embroidered the King’s garter robes herself. 3 While Henry VII and Elizabeth were rarely parted, he liked to keep his wife by his side when he travelled, even on diplomatic missions.

Erasmus described visiting the family home, Eltham Palace, during his first visit to England in 1499 and encountering the royal children in the hall.

“In the midst stood Prince Henry, now nine years old and having already something of royalty in his demeanour, in which there was a certain dignity combined with singular courtesy. On his right was Margaret, about eleven years of age, later married to James, king of Scots; and on his left played Mary, a child of four, Edmund was an infant in arms.”4

Henry VII and Elizabeth were ambitious for their children’s education. Prince Arthur’s education was modelled on the programme that had been drawn up for Elizabeth’s own brothers. Henry would take up a classical curriculum under poets such as Bernard André and John Skelton, and would be heavily influenced by Desiderius Erasmus and Thomas More. However, it was his mother who taught him his basic skills of reading and writing. On the 2nd of November 1495, Henry VII paid £1 ‘for a book bought for my Lord of York’. Henry was only four and a half and there is no trace of a formally appointed tutor. David Starkey concludes that it was Elizabeth who taught Henry to read. His handwriting was quite unlike that of his known teachers, and in some ways very like his sister’s handwriting and Starkey suggests it was also Elizabeth who taught her children to write. Elizabeth herself had received a remarkable education for a fifteenth-century woman. 5

A Hateful Intelligence

Henry had experienced death at a tender age. His sister Elizabeth died when he was only four, and he would also lose his brothers Edmund and Edward. 6 Infant death was far more common in the middle-ages but their deaths would have of course affected him. But when Henry was eleven true catastrophe struck his family. His newly-married eldest brother Prince Arthur died unexpectedly at age sixteen. Arthur, named to strengthen Henry VII’s alleged descent from the ancient British kings, was considered the great hope of the Tudor dynasty. His death was a grievous blow to Henry VII and Elizabeth. Young Henry had shared a nursery with his brother briefly, but as age six Arthur had been sent off to his own household in Wales. It was his mother’s death less than a year later that would have a terrible impact on Henry.

For never, since the death of my dearest mother, hath there come to me more hateful intelligence. . . . It seemed to tear open again the wound to which time had brought insensibility – Henry VIII to Erasmus 7

The Vaux Passional has been in the National Library of Wales since 1921, but it was only last year the significance of the first illumination in the manuscript was discovered. It is now believed that the illumination is a depiction of the Tudor family grieving the late Queen Elizabeth. “The only occasion when there were three children (one boy and two girls) in the Tudor court was after the death of Arthur in April 1502, and before Margaret’s marriage to James IV of Scotland in August 1503. Next comes the black head-dresses worn by the girls, the black-draped bed under black hangings, the broken ‘lock’ (possibly symbolising the breach by death in the mortal marriage), the crying figure (with reddish hair), and the king’s black dress (under his robe),” said Dr Maredudd ap Huw. 8 The crying figure in the top left corner is thought to be one of the earliest representations of Henry VIII. While Henry’s grief at his mother’s death has long been known, it is a rather remarkable depiction of a young Henry grieving for his beloved mother. His mother’s death would change his father. Henry not only saw, but felt the true impact of his brother and mother’s death within a year of each other. When his mother’s gentle influence was gone, the “dark prince” we now associate with the last few years of Henry VII’s reign would emerge, and Henry, now the heir to the throne, would spend the next few years cloistered in his father and grandmother’s overprotective shell, his carefree childhood snatched from him.

The Quest for a Perfect Wife

Henry VII would join his beloved wife only six years after her death. By this time Prince Henry and his father had grown somewhat distant, and when Henry came into his own, he came into it with a vengeance. His father was not mourned for long. The people rejoiced when Henry VIII took the throne, and with a flourish he executed his fathers two main advisers and married his brother’s widow. Katherine of Aragon had spent the years since Prince Arthur’s death in increasing penury. After Arthur’s death her betrothal to Henry had been quickly arranged, but then her mother died. Katherine became the victim of a power struggle between two kings, Henry VII and her own father Ferdinand of Aragon. But Henry VIII, who had escorted the beautiful Princess Katherine to her wedding when he was an eleven year-old boy, was now determined to play the role of chivalrous knight and sweep her off her feet. She was still young and beautiful and only six years older than her intended groom. She was a princess of the greatest monarchy in Europe. Katherine was raised from birth to be royal, was intelligent and pious and she came from fertile stock. Just like his dearest mother. What more could Henry want from a wife?

The cataclysmic events that would lead to Henry abandoning his wife and the break with Rome will always overshadow the early, happy years of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon. They were young, in love and led a lavish lifestyle, just as Henry’s parents had done. Katherine’s second pregnancy was successful, and gave Henry a prince. Little Henry, Duke of Cornwall, is often forgotten. When he was born the public fountains flowed with wine, tournaments and celebrations were planned. King Henry VIII was in his element. But tragically, little Prince Henry would die only a month later. Katherine spent the next eight years desperately trying to give her husband an heir. Katherine only had one live birth, a girl, and by the 1520’s Henry was despairing that he would never leave the succession secure.

Henry did not, as is often assumed, “tire” of Katherine simply because she was ageing and no longer able to conceive. Had his first son lived this would not have been an issue. Francis I may have called Katherine “old and deformed” (“deformed” meaning overweight) but Francis was a varlet who drove his own wife to an early grave by using her as a brood-mare while he slept around. Despite a handful of affairs Henry was a devoted husband. Henry’s own mother had lost her youthful figure due to her many pregnancies. The same would happen to Katherine. Henry was not concerned with his wife’s looks or age, Henry was concerned that more than fifteen years of marriage had failed to produce an heir, or a son, in any case. He had a healthy daughter, Princess Mary was much beloved by his subjects. But Henry convinced himself that he was being punished by God for marrying his brother’s widow. He dwelt more and more on the succession.

Queen Elizabeth of York did not live to see her son crowned. Had she outlived her husband she may have lived on to see her son marry Katherine of Aragon, perhaps her gentle influence may have rubbed off on her son. It is sad to speculate what Elizabeth would have made of her son’s disastrous marriages. Henry VIII really only wanted what his parents had, a loving marriage blessed with many children. Henry, in fact, thought himself in love with all of his wives, even the ill-fated (or fortunate if you like) Anne of Cleves. But love was not enough. They must give him a son. He did not get his heart’s desire for almost three decades. It was his third wife Jane Seymour that gave him the son he longed for. While even today people find it difficult to imagine what Henry saw in the plain, pale and meek Jane, it was Jane who finally achieved what his mother had achieved. She had given her husband a prince.

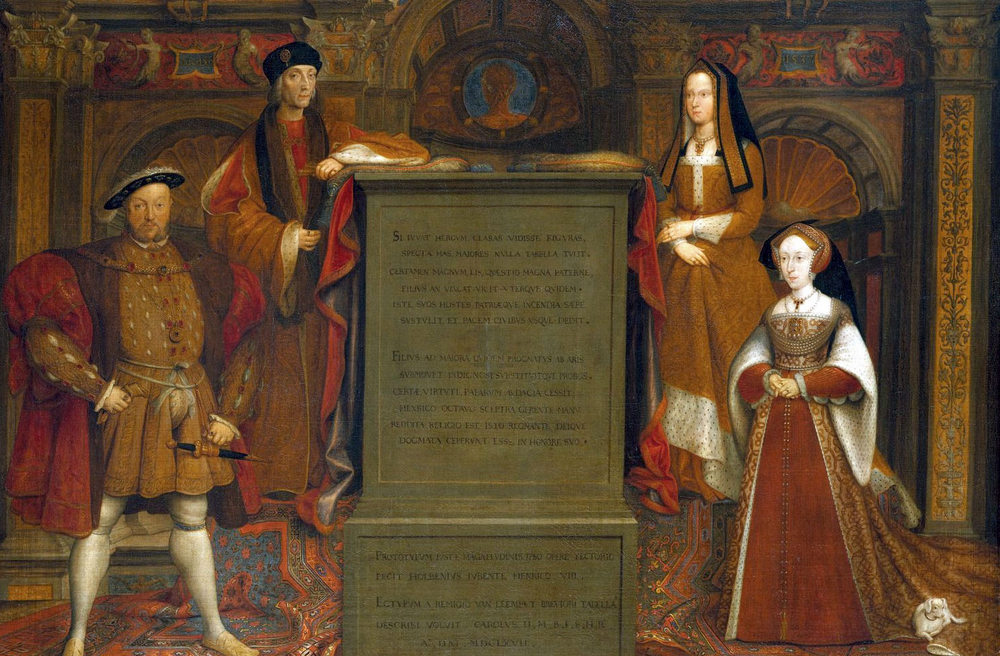

But Jane died from complications after childbirth. Jane could no longer give him the complete family he craved. Another two disastrous marriages would follow. It was Henry’s sixth wife Catherine Parr who would finally give Henry some of the stability he longed for. Catherine brought together his three children, all of different mothers, and forged a close family. All of Henry’s children, Mary, Elizabeth and Edward loved their stepmother dearly, and could finally enjoy something of a normal family existence. But Catherine never gave Henry a child, he was too old and sickly to father children by then. It is why Henry chose to be buried with Jane Seymour, and not his last wife Catherine. Henry called Jane Seymour his “true wife”. It was Jane Seymour who was immortalised in Henry’s family portrait, long after her death. It was Henry’s ideal, the ideal that his own parents had created.

- The Funeral Sermon of Margaret, Countess of Richmond and Derby … Preached By Saint John Fisher pg 179 ↩

- Okerlund, Arlene Elizabeth of York Palgrave Macmillan 2011, pg 136-139 ↩

- Weir, Alison Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen, Jonathan Cape 2013, pg 271 ↩

- Okerlund, Arlene Elizabeth of York Palgrave Macmillan 2011, pg 136 ↩

- Starkey, David, Henry – Virtuous Prince, Harper Perennial 2009, pg 118-19 ↩

- The birth and death date of Edward Tudor is unrecorded ↩

- The Letters of Henry VIII ↩

- History Extra Portrait may show young Henry VIII ↩