This week we have been discussing the festive season in Tudor England, and largely the nobility’s version of Christmas, with celebrations and games and lavish banquets marking the end of a fasting period – fasting which was by no means arduous for the wealthy. Christmas was the one time of year the poor could be guaranteed a plate of meat, at Christmastide the working classes would be provided with a good meal and entertainment from their Lord. The homeless would have access to poor relief and food during the festive period. So how is it that the Little Match Girl died, frozen in the snow, on New Year’s Eve, three centuries later?

In Tudor times “vagrant” children could be seized by any adult who purported to teach them a trade, with permission from the parents being unnecessary. The Tudors also supposed there were simply two kinds of poor, those who begged because they could not work and those who enjoyed ‘the lifestyle’, called ‘sturdy beggars’. A contemporary description of a ‘rogue’ goes to great lengths describing how, if given clean clothing, the vagrant would sell it to pocket the money and still appear poor enough to beg.1 Three centuries later begging was still illegal in many cities, and the Little Match Girl’s father would have sent her out begging in the hope that she would garner more sympathy than his adult self. The poor and homeless have been treated as invisible for centuries. Society has never been structured for the poor to be treated with respect, let alone the homeless.

Published just before Christmas in 1845, The Little Match Girl was conceived when Hans Christian Andersen received a packet of three illustrations with a request that he create a story from one of them. Andersen chose an illustration by Danish artist Johan Thomas Lundbye that showed a girl selling matches. The drawing had already appeared in an 1843 calendar accompanied by the charitable plea, “Do good when you give.” Andersen, who was brought up in a poor household and forced to fend for himself from an early age, was thinking of his mother’s own experience; she was also raised in dire poverty and she was often sent out to beg. When she had no luck, she would hide under a bridge and cry. Andersen said that “As a child, I imagined all of this so clearly and I cried about it”. And so this tragic tale of poverty was written in less than a week while the now-successful Andersen was staying with the Duke of Augustenborg at Graasten Castle, in Jutland.2

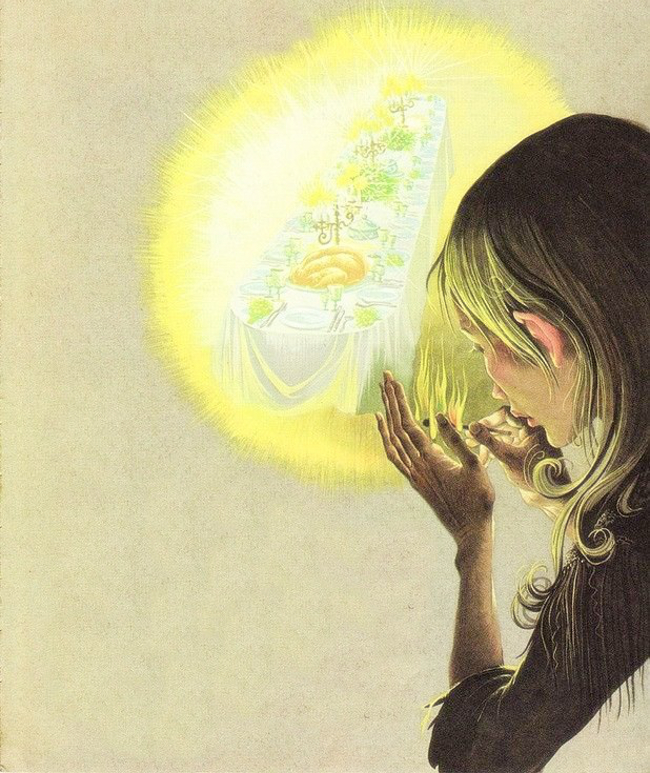

The Little Match Girl tells the story of a young girl forced out onto the streets on New Year’s Eve to sell matches, a cover for begging. Having not sold anything all day, lost her shoes and rapidly beginning to freeze, she is too scared to return home, where her father will likely beat her. So the Little Match Girl takes shelter in a nook between two houses, and begins to strike the matches for warmth. She sees visions of a warm stove, a roast dinner and finally her grandmother, “the only person who had been nice to her”. And after she strikes the last match:

“Grandma!” the little girl called out. “Take me with you! I know you’ll be gone when the match goes out — gone like the warm stove, the wonderful roast goose, and the big beautiful Christmas tree.” She quickly lit the rest of the matches in the bunch; she so wanted Grandmother to stay. The matches burned with such brilliance that they were brighter than the light of day. Grandmother had never been so beautiful or so tall; she lifted the little girl in her arms, and they flew higher and higher in light and joy. There was no more cold, no hunger, no fear — they were with God.

But in the cold dawn, the girl sat in the nook by the house. She had rosy cheeks and a smile on her lips: She was dead, frozen to death on the last night of the old year. New Year’s morning brightened over her little body, sitting with her matches; most of the bunch had been burned. She had wanted to get warm, people said. No one knew the beauty she had seen or in what glory she had gone with her old grandmother into the joy of the New Year.3

While the social commentary of The Little Match Girl is evident, Andersen believed he had given her a happy ending in the afterlife, with a version of his own beloved grandmother accompanying her into the arms of the Christian God.4 Not everyone was convinced. One translator sought to change the ending, telling readers that “The little match girl on that long ago Christmas Eve [sic] does not perish from the bitter cold, but finds warmth and cheer and a lovely home where she lives happily ever after.”5 Although it is often said that the ending has been changed by many translators, most versions retain the original. However, there is one alternate ending to The Little Match Girl that can be found in another kind of fairytale, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess.

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess has always suffered a little in comparison to The Secret Garden, despite the latter being a traditional and fairly pedestrian tale of the spoiled child coming good after a dose of fresh country air and common sense. A Little Princess has its own traditional roots, a riches-to-rags-to-riches Cinderella type tale, only with a far more serious and complex little heroine. Sara Crewe was once a girl of immeasurable wealth, now left a destitute orphan in the cruel hands of her headmistress Miss Minchin, who treats her like a slave; alongside the scullery maid Becky. Both girls are often deprived of food, and comfort each other in the squalid conditions they are forced to live in, the freezing cold and damp attic rooms at the top of the school.

But it is Guy Clarence who gets the ball rolling. Sarah often looks in on a family she has named ‘The Large Family’ as she goes about her errands, yearning for a family to love again.

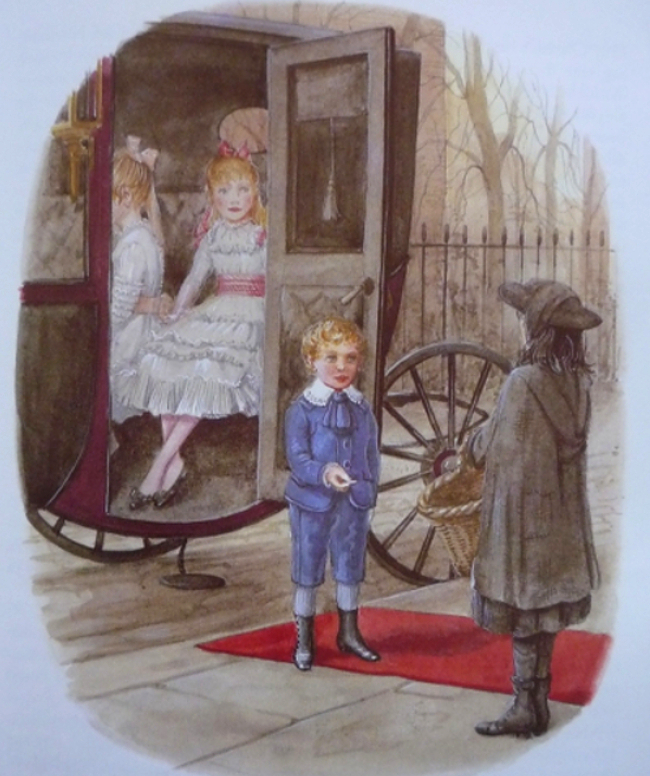

It was Christmas time, and the Large Family had been hearing many stories about children who were poor and had no mammas and papas to fill their stockings and take them to the pantomime—children who were, in fact, cold and thinly clad and hungry. In the stories, kind people—sometimes little boys and girls with tender hearts—invariably saw the poor children and gave them money or rich gifts, or took them home to beautiful dinners. Guy Clarence had been affected to tears that very afternoon by the reading of such a story, and he had burned with a desire to find such a poor child and give her a certain sixpence he possessed, and thus provide for her for life. An entire sixpence, he was sure, would mean affluence for evermore. As he crossed the strip of red carpet laid across the pavement from the door to the carriage, he had this very sixpence in the pocket of his very short man-o-war trousers; And just as Rosalind Gladys got into the vehicle and jumped on the seat in order to feel the cushions spring under her, he saw Sara standing on the wet pavement in her shabby frock and hat, with her old basket on her arm, looking at him hungrily.

He thought that her eyes looked hungry because she had perhaps had nothing to eat for a long time. He did not know that they looked so because she was hungry for the warm, merry life his home held and his rosy face spoke of, and that she had a hungry wish to snatch him in her arms and kiss him. He only knew that she had big eyes and a thin face and thin legs and a common basket and poor clothes. So he put his hand in his pocket and found his sixpence and walked up to her benignly.

“Here, poor little girl,” he said. “Here is a sixpence. I will give it to you.”

Embarrassed at her shabby state, Sara tries to refuse the sixpence, but Guy Clarence is so insistent that she cannot bear to break his heart. She wears his sixpence around a string on her neck as a keepsake. It is weeks later during the bitterly cold winter when Sara has the good fortune to find a fourpenny bit in the snow, just outside a bakery, and this one she can spend. But she also encounters a little figure in the snow.

It was a little figure more forlorn even than herself—a little figure which was not much more than a bundle of rags, from which small, bare, red muddy feet peeped out, only because the rags with which their owner was trying to cover them were not long enough. Above the rags appeared a shock head of tangled hair, and a dirty face with big, hollow, hungry eyes.

Sara knew they were hungry eyes the moment she saw them, and she felt a sudden sympathy.

“This,” she said to herself, with a little sigh, “is one of the populace—and she is hungrier than I am.”

The child—this “one of the populace”—stared up at Sara, and shuffled herself aside a little, so as to give her room to pass. She was used to being made to give room to everybody. She knew that if a policeman chanced to see her he would tell her to “move on.”

Sara clutched her little fourpenny piece and hesitated for a few seconds. Then she spoke to her.

“Are you hungry?” she asked.

The child shuffled herself and her rags a little more.

“Ain’t I jist?” she said in a hoarse voice. “Jist ain’t I?”

“Haven’t you had any dinner?” said Sara.

“No dinner,” more hoarsely still and with more shuffling. “Nor yet no bre’fast—nor yet no supper. No nothin’.

“Since when?” asked Sara.

“Dunno. Never got nothin’ today—nowhere. I’ve axed an’ axed.”

Just to look at her made Sara more hungry and faint. But those queer little thoughts were at work in her brain, and she was talking to herself, though she was sick at heart.

“If I’m a princess,” she was saying, “if I’m a princess—when they were poor and driven from their thrones—they always shared—with the populace—if they met one poorer and hungrier than themselves. They always shared. Buns are a penny each. If it had been sixpence I could have eaten six. It won’t be enough for either of us. But it will be better than nothing.”

“Wait a minute,” she said to the beggar child.

Sara goes in to the bakery to purchase four penny buns, and the kind-hearted baker gives her six.

“I’ll throw in two for makeweight,” said the woman with her good-natured look. “I dare say you can eat them sometime. Aren’t you hungry?”

A mist rose before Sara’s eyes.

“Yes,” she answered. “I am very hungry, and I am much obliged to you for your kindness; and”—she was going to add—”there is a child outside who is hungrier than I am.” But just at that moment two or three customers came in at once, and each one seemed in a hurry, so she could only thank the woman again and go out.

The beggar girl was still huddled up in the corner of the step. She looked frightful in her wet and dirty rags. She was staring straight before her with a stupid look of suffering, and Sara saw her suddenly draw the back of her roughened black hand across her eyes to rub away the tears which seemed to have surprised her by forcing their way from under her lids. She was muttering to herself.

Sara opened the paper bag and took out one of the hot buns, which had already warmed her own cold hands a little.

“See,” she said, putting the bun in the ragged lap, “this is nice and hot. Eat it, and you will not feel so hungry.”

The child started and stared up at her, as if such sudden, amazing good luck almost frightened her; then she snatched up the bun and began to cram it into her mouth with great wolfish bites.

“Oh, my! Oh, my!” Sara heard her say hoarsely, in wild delight. “OH my!”

Sara took out three more buns and put them down.

The sound in the hoarse, ravenous voice was awful.

“She is hungrier than I am,” she said to herself. “She’s starving.” But her hand trembled when she put down the fourth bun. “I’m not starving,” she said—and she put down the fifth.

The little ravening London savage was still snatching and devouring when she turned away. She was too ravenous to give any thanks, even if she had ever been taught politeness—which she had not. She was only a poor little wild animal.

“Good-bye,” said Sara.

When she reached the other side of the street she looked back. The child had a bun in each hand and had stopped in the middle of a bite to watch her. Sara gave her a little nod, and the child, after another stare—a curious lingering stare—jerked her shaggy head in response, and until Sara was out of sight she did not take another bite or even finish the one she had begun.

Sara’s act of kindness has a far bigger effect than she could have imagined. When Sara has her fortune back and has been adopted by her late father’s friend, she visits the bakery once more. There she learns that after the baker saw Sara give the little beggar girl five of her buns, the baker invited the girl in to get warm. Anne, as the little beggar girl is called, now lives at the bakery and the baker-woman confesses to Sara that ” I’m bound to say I’ve given away many a bit of bread since that wet afternoon, just along o’ thinking of you—an’ how wet an’ cold you was, an’ how hungry you looked; an’ yet you gave away your hot buns as if you was a princess”. And Sara asks Anne to be in charge of giving away bread to beggar children on her behalf. Anne is now a member of society as she deserves to be, no longer invisible. And thus, Sara Crewe saved the Little Match Girl from freezing to death in the snow.

Sources:

Frank, Diana Crone & Frank, Jeffrey, The Stories of Hans Christian Andersen, Duke University Press 2005

Pound, John, Poverty and Vagrancy in Tudor England, Longman 1986

Marvels & Tales Vol. 20, No. 2, “Hidden, but not Forgotten”: Hans Christian Andersen’s Legacy in the Twentieth Century, 2006