Stan Lee, creator of Spider-Man, X-Men, The Hulk, The Fantastic Four, and maybe half the comic books you’ve ever heard of said in a recent interview about the creation of the Fantastic Four, “I tried to violate some of the usual comic book rules. I felt I wouldn’t give them secret identities because I’ve always felt if I had a super power, which is not to say that I don’t, there’s no way I would want to hide the fact I mean, I’m a conceited guy. I’d run around, “Hey, look at me. I’m super.” I wouldn’t wear a mask and I certainly wouldn’t walk around in a stupid costume.”

Stan Lee, creator of Spider-Man, X-Men, The Hulk, The Fantastic Four, and maybe half the comic books you’ve ever heard of said in a recent interview about the creation of the Fantastic Four, “I tried to violate some of the usual comic book rules. I felt I wouldn’t give them secret identities because I’ve always felt if I had a super power, which is not to say that I don’t, there’s no way I would want to hide the fact I mean, I’m a conceited guy. I’d run around, “Hey, look at me. I’m super.” I wouldn’t wear a mask and I certainly wouldn’t walk around in a stupid costume.”

However, even the public persona of an ordinary person creates a second self, the second self of the maskless super hero, is itself a mask. As Freud has it, the alter ego, the mysterious double, the stranger within is created by repression, giving a mask to that hidden face, allows it to emerge, gives design and reign to all the hidden desires, the suppressed conflicts, the instinctual urges, creating both villain and hero.

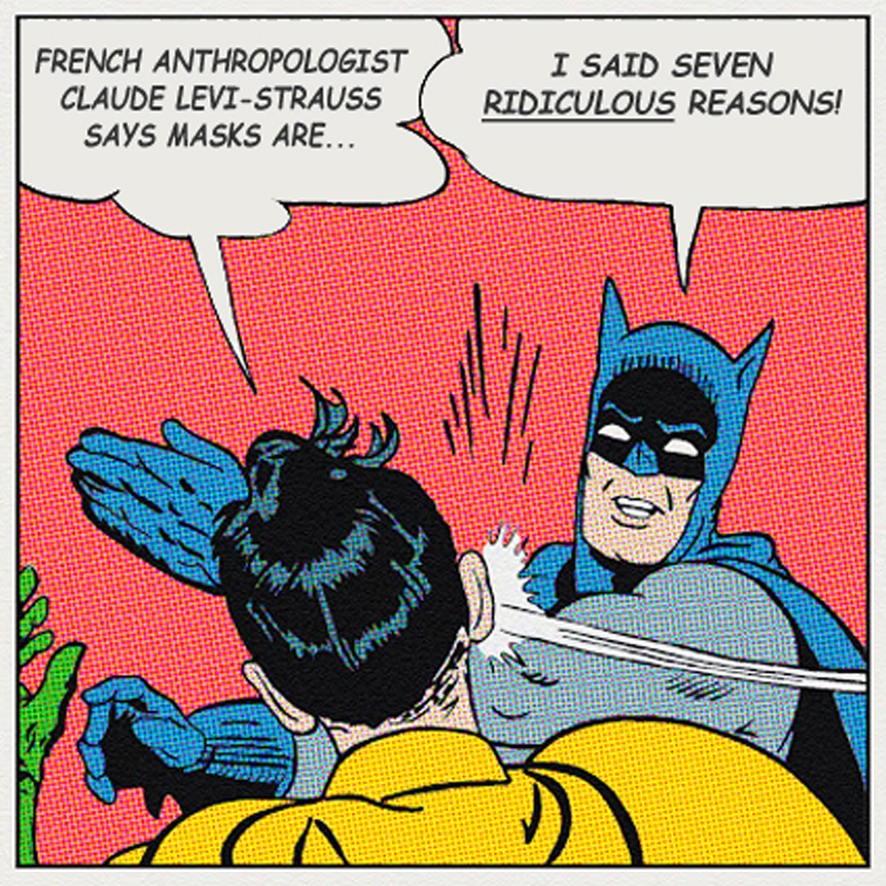

As with French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, who in The Way Of The Mask, a study of the cultural significance of masks amongst native American peoples of the Pacific Northwest, found that masks and their myths were inseparable, that seemingly disparate characters “echo and transform each other,” and that in different cultures the structure of myths were essentially the same, involving opposed forces, which were resolved or mediated often by a masked trickster. Curiously enough, in the complex mythologies of comic books, in which heroes can become villains and vice versa, both can take on the role of trickster.

Whether the mask is as simple as paint, or as complex as a persona, whether it has origins in indigenous cultures, the ancient mythologies of the Greeks or the Norse, the DC or the Marvel Universe, while sometimes we may not recognize each other, we will always find familiarity, shared humanity in the masks we all wear.