No, I have not suddenly become some sort of Scientifical Creationist, invoking an existential timescale accelerated to match the speed of life in what is probably the late part of the Anthropocene era. Rather, it is the eminent scientific journal, Nature, (itself not unfamiliar to ludicrous propositions), which was first published on the 4th of November, 1869, that has reached its sesquicentennary.

Oddly enough, that first issue began with something we would seldom associate with science today — the admonitions of two romantic poets; a motto under the header, from Wordsworth;

To the solid ground of Nature trusts the Mind that builds for aye.

Then a page, in two neat columns, of aphorisms from Goethe, describing the metaphorical figure in all her conundrums and complexities, ending with this;

She wraps man in darkness and makes him for ever long for the light. She creates him dependent upon the earth, dull and heavy; and yet is always shaking him until he attempts to soar above it.

Nature, published by Alexander Macmillan and edited by Norman Lockyer, began as a popular journal, aimed at a curious and newly educated public, with no lesser purpose than through the promotion of science, to change the world. Its early contributors were liberal, progressive, sometimes controversial; supporters of Charles Darwin’s theories on the descent of man and evolution by natural selection, theories by no means accepted by much of the established scientific community, let alone a still dubious public.

In a world that had barely left behind a kind of superstitious, agog clamouring at inexplicable signs and portents, that still quailed at the return of Halley’s Comet in 1819, Nature, combining literature, journalism, science and adventure, instead sought reason. In the confluence of rational inquiry, and the explication of the natural world in all her details, a new kind of wonder, suited to the spirit of a new and burgeoning world. A world where human-made engines now unified the civilised world, and where the divine might still be found in the intricate unfolding of a butterfly’s wing, if not in a hurricane. Of course, today, we still might find, in the wing, the divine, but in the hurricane, lent power through science, our own reckless, grasping hand.

From being a populist organ of gentleman scholars and amateur scientists, Nature, through the years, has evolved into a more rigorous multidisciplinary journal.

Rigorous and prestigious as it is, I doubt today you would find a loosely quipped anecdote, like Darwin’s of Thursday, 3rd April, 1873, addressing some flimsy critique of his theory of inheritance of traits in natural selection, where he describes how the renowned ornithologist, Audubon, “kept a pinioned wild goose in confinement, and when the period of migration arrived, it became extremely restless, like all other migratory birds under similar circumstances; and at last it escaped. The poor creature then immediately began its long journey on foot, but its sense of direction seemed to have been perverted, for instead of travelling due southward, it proceeded in exactly the wrong direction, due northward.”

His other evidence that traits are inherited, not through physical transmission, from the learned experience of the parent to offspring, but from some as yet unknown inherent means, is both more scientific, and more cruel; he recounts an experiment in which pigeons were pricked with a needle in the base of the brain. “Birds thus treated roll over backwards in convulsions, in exactly the same manner as do the ground-tumblers; and the same effect is produced by giving them hydrocyanic acid with strychnine. One pigeon which had its brain thus pricked recovered perfectly, but continued ever afterwards to perform summersaults like a tumbler, though not belonging to any tumbling breed.”

Darwin thought it was something in the brain that recorded such behaviours, where the trait of the species was passed on, regardless of whether any particular antecedent partook of that behaviour. It was Nature, in 1953, only 80 years later, in a paper by Crick and Watson, that indelibly brought the solution to that puzzle; that all that we are, from our appearance, to our behaviours, even to our strange curiosities and predilections for self-destruction, at their roots, are recorded in the twisting coil of the DNA molecule. Prick us and do we not bleed? Or fall over backwards, writhing on the floor?

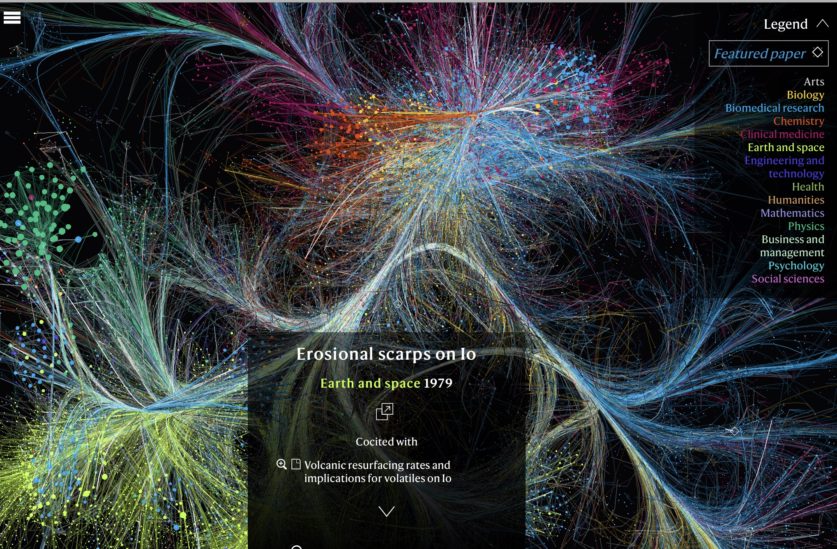

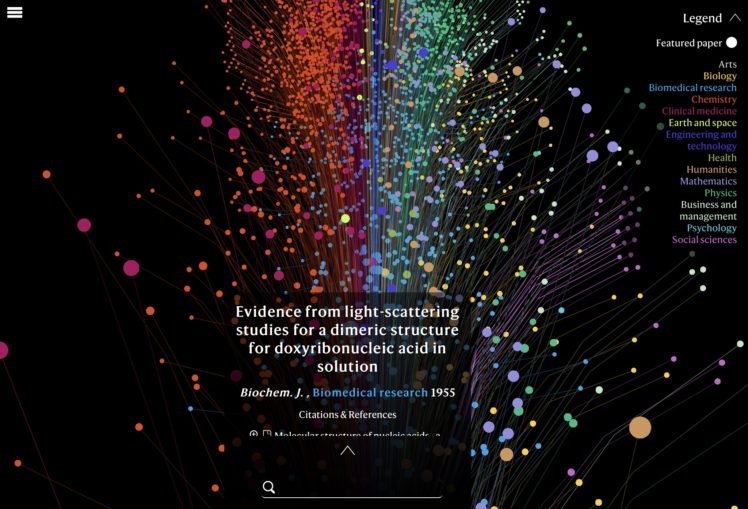

Nature has gone on to be the most cited scientific journal of all time, and to celebrate 150 years of that research, they have created an interactive map, like a collection of nerve fibres, pricked through with historic moments, or perhaps a galaxy, where those cited papers are the suns and the planets, mapping a universe that in some ways defines where we are now, but in others, reminds us; this is the late, late Anthropocene era, made great by our relentless inquiry, also, perhaps, made the last by them.

Maybe, after all, science still needs to first listen to the poets.