“…a legend tells how Zeus winged his way to my mother Leda’s breast, in the semblance of a bird, even a swan, and thus as he fled from an eagle’s pursuit, achieved by guile his amorous purpose, if this tale be true. My name is Helen, and I will now recount the sorrows I have suffered.”

-Euripides, Helen

Some say that Zeus once fell in love with Nemesis, and pursued her over the earth and through the sea. Though she constantly changed her shape, he violated her at last by adopting the form of the swan, and from that egg she laid came Helen, the cause of the Trojan War.

-Robert Graves, The Greek Myths

Zeus, ruler of the Olympian Gods, was an adulterer, rapist and deceiver, and Greek mythology presents him as such. Mythology may have romantic themes, but the telling is always straightforward. A rape is a violation, a deceit. There is nothing ambiguous about it. Therefore, the story of Leda and the Swan should be read in its historical and mythological context. The well-known version sees Zeus adopt the form of a swan, an animal which was considered sacred, and deceive Leda, variously known as Nemesis or even Zeus’s daughter, Tyche.1 Whoever the protagonist, the myth always ends in violation.

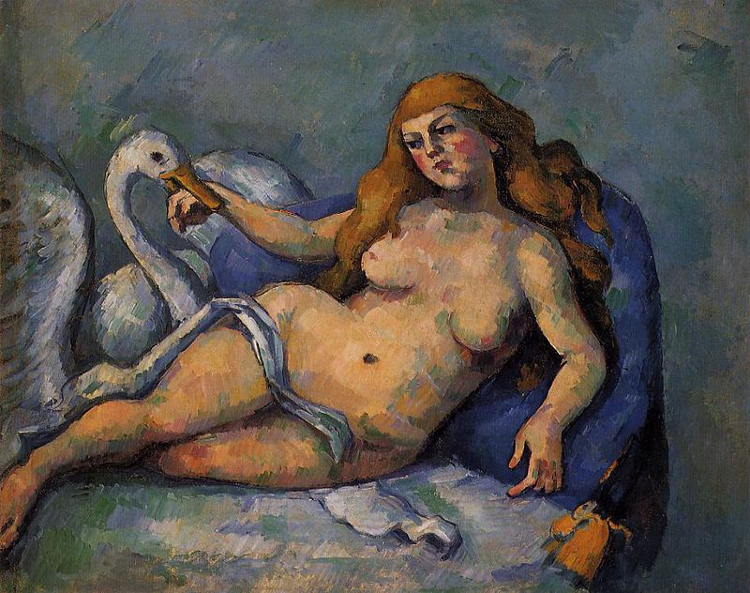

Leda has long been an artist’s muse. There have been many, many revisionist tellings of her plight, only some are far removed from the original myth, and various readings of those texts complicate matters further. Commonly thematic is the eradication of violence from Leda’s plight, Leda’s encounter with Zeus becomes an erotic one, where Leda in an active participant, rather than the victim of a rape. The beauty of Zeus’s form as the swan and its many representations in paintings and sculpture, who also often depict Leda in sexual acquiescence,2 may, in fact, be the real muse.

Still, many of the adaptations of Leda and the Swan continue to depict Leda as the sacrifice. A notable exception is Hilda Doolittle, or H.D.’s, Leda. The poem opens with a rich description of the swan, immediately attracting the reader to his beauty. His breast is ‘soft’,3 thus, inviting, rather than oppressive. The poem unfolds languidly, with images of caresses, floating, drifting, evoking a long sun-drenched afternoon of lovemaking. Leda is completely preoccupied with her pleasure, crying Ah kingly kiss—/no more regret/nor old deep memories/to mar the bliss. As the poem concludes the swan’s breast is warm and quivering, reflecting the ecstasy of orgasm – the same breast that, in other adaptations of Leda, is used with force against its victim.

The poem lacks the authenticity of Leda’s experience. H.D.’s poetical imagery was based on the American landscapes of her youth.4 Leda is now in a landscape and experience familiar to the poet, not to the protagonist. There are many feminist readings of H.D.’s Leda, yet by revising Leda’s experience to an erotic one, H.D. has not necessarily empowered her, rather the poem has restrained Leda, exploring only a ‘restricted terrain of sensibility’.5 The use of ‘regret’ and ‘memories’ must be questioned. Leda casting off ‘regrets’ might represent her embracing her sexuality, and the ‘memories’ society’s fettering of women’s sexual freedom; yet when the protagonist’s tale has long been one of violation, casting off supposed regrets makes her complicit in her own assault. By casting off regrets and memories Leda is ‘giving in’ to her sexuality, therefore it is suggested that non-consensual sex can still be desired by the victim, and that women only refused sex because of societal restraint.

Leda – Robert Graves

Heart, with what lonely fears you ached,

How lecherously mused upon

That horror with which Leda quaked

Under the spread wings of the swan.Then soon your mad religious smile

Made taut the belly, arched the breast,

And there beneath your god awhile

You strained and gulped your beastliest.Pregnant you are, as Leda was,

Of bawdry, murder and deceit;

Perpetuating night because

The after-languors hang so sweet.6

Robert Graves’ translation of the Greek myth described Leda’s encounter with Zeus as a ‘violation’. Yet his poem is underpinned by the role of female complicity. Graves’s protagonist desires the act Perpetuating night because/The after-languors hang so sweet. Many male poets have adapted Leda’s story, and many male readings of those poems lean towards Leda as the instigator, some even posit Leda as the rapist. W.B. Yeats’s Leda and the Swan has been heavily analysed, with some readings displaying distinctly male sexual anxieties.

W.C Bardwell thinks that Yeats’s Leda remains ambiguous and never really makes clear who the rapist is, even offering the suggestion of a ‘third party’ rapist.7 Bernard Levine suggests that Zeus was so ‘staggered’ by Leda’s beauty he was ‘forced’ to rape her; optimistically suggesting that ‘the girl may be construed as struggling in such a way as to have forced ‘her nape’ into ‘his bill’ making him helpless’ 8 John F. Adams claimed that Leda ‘actively participates in the sexual experience’ and ‘takes a kind of mastery over the man. . .There is almost a suggestion of the infant in this god’s heart beating against the captive but still maternal breast of Leda, a feeling which is not, I believe, unusual for the female in her sexual climax’. 9 Adams claims that Yeats’s poem gives an insight into ‘the female’s passive role in sex’ and ‘the mystery of woman’s passive pleasure in being violated’.10 C.F Macyntire further compounds a male fear of female sexuality by wishing that ‘Dante put Leda in his seventh circle, where she richly belonged for having violated nature’.11

Leda and the Swan – W.B. Yeats

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop? 12

Yeats’s poem is, in fact, a traditional telling of Zeus’s rape of Leda, and focuses on the trauma without ambiguity. The poem opens with violence A sudden blow” knocks Leda staggering. The swan then traps Leda’s neck in his bill, and “holds her helpless breast upon his breast. Yeats asking How can those terrified vague fingers push/The feathered glory from her loosening thighs? could be construed as ambiguous, Leda’s thighs may be ‘loosening’ with desire, yet this takes the line out of context. It is clear, overall, that Yeats is depicting, not only a rape, but a discarding of the victim after the act. Yeats closes the poem asking Did she put on his knowledge with his power/Before the indifferent beak could let her drop? Yeats, an Irishman, may be using Leda as an image of resistance to colonial oppression. Janet Neigh notes that the poem ‘conveys a resistance to colonial occupation; even after the violence, Leda manages to stay on her feet.’13 When Yeats asks Did she put on his knowledge with his power?, he references the Imperial myth of biological superiority, cleanliness, education and assimilation used to justify colonial violence. It is a far cry from the ‘evil temptress’ readings of his Leda.

Leda – D.H. Lawrence

Come not with kisses

not with caresses

of hands and lips and murmurings;

come with a hiss of wings

and sea-touch tip of a beak

and treading of wet, webbed,

wave-working feet

into the marsh-soft belly 14

D.H. Lawrence’s short poem Leda depicts the attacker, rather than the attack itself. Lawrence avoids placing himself in Leda’s role, yet he focuses on her victimisation, the key image, deception. Come with a hiss of wings/and sea-touch tip of a beak/and treading of wet, webbed, wave-working feet/ into the marsh-soft belly. The soft noises announce Zeus’s stealthy arrival, his feet working their way into Leda’s belly represent the penetration, or violation of her body.

Of the male poets who have explored the Leda myth, Helen Sword suggests that ‘these same poets proved conspicuously unwilling, in their literary responses to the Leda myth, to place themselves fully in the imagined role of the female’.15 Rainer Maria Rilke’s Leda 16 poses this problem in that it identifies directly with the attacker – and suggests an excusion of his actions. As if some sort of madness has overtaken the swan, the narrator claims that before he could probe what it meant to be and to feel in this strange way. And what gaped wide in her”[…]”he asked for the one thing that she/ tangled in resisting him, could no longer/withhold. Not asserting if Leda could ‘no longer withhold’ from Zeus because he had overpowered her physically, or if she herself had been overcome with desire, leaves the attack ambiguous.

Sword observes that “Women writers confronting the Leda myth[…]might reasonably be expected to identify, at least in imagination, with Leda and her plight”.17 Janet Neigh notes that “the hybridity of the swan, as both masculine and feminine as well as animal and divine, coerces readers to identify with the figure.”18 Although the gender is most often specified (almost all of the poems discussed here refer to the swan in the male) the ‘hybridity’ is suggested in the animal form that Zeus has taken on, rather than a specification of gender. The image of the swan is aesthetic, a beautiful creature, an image that lacks the urgency of the violence had the attacker been portrayed as a man.

Modern female poets offer some fascinating images of Leda. Lucille Clifton’s Leda 3 19 jeers You want what a man wants/next time come as a man/or don’t come, referencing the restriction of sexual freedom for women. Nina Kossman’s poem Leda 20 presents a powerful ancestral memory hung in lulled air like an ancestor’s soul, heavy,/ languid, and waiting for an infusion of flesh, but Kossman’s Leda is still not in control of her destiny. Leda’s fate, the mother of the nation of myth makers/the generation of myth transforming itself into memory is her diminishment. She has become her children’s light/gentler than her memory but still not in her full command, Kossman’s Leda has become a mother to her children, but her own self is not fully realised.

Mona Van Duyn’s Leda 21 suffers an even more mundane fate. Van Duyn opens the poem quoting the last two lines of Yeats, answering his question Did she put on his knowledge with his power/Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?. Not even for a moment answers Van Duyn, he knew, for one thing, what he was/When he saw the swan in her eyes, he let her drop. Van Duyn presents a Leda who is so unimportant, after her violation, used and discarded, that she was not ‘abstract enough’ for a romantic death of any sort. Instead She married a smaller man with a beaky nose/and melted away into the storm of everyday life. Leda is weakened here by becoming ordinary.

Barbara Bentley’s powerful take, Living Next to Leda 22 sees the tragic loss of Leda’s sanity, presenting a bleak look at a rape victim whose voice is not heard. This Leda has suffered severe mental trauma after her attack, she can still hear the swan, even though swans are mute. But Leda insists she can hear them as white sound. The narrator tells us that Leda had a nervous tic triggered by/sparrows that twitched in her garden./She said they flitted about like bits of grit/granted flight. The narrator is sympathetic, she cleans feathers off Leda’s window when Leda cannot bear to touch them herself, she makes her tea, yet she calls her Crazy Leda who heard swans with the conspiratorial air of a neighbourhood gossip. Yet none of this tells the reader what had happened to Leda, it is only in the closing lines of the poem that the narrator reveals her secret, when she visits Leda in the mental asylum. Soon, the narrator says, there will be twins while the bastard that did this flies free. These various female poets present Leda as a victim, not only of a sexual assault, but on a wider scale, as a victim of a patriarchal society. There is nothing in the experience that empowers Leda, because Leda is a victim.

Revisions of the Leda myth have and continue to present Leda as a victim. Leda was a sacrifice to both sexual violence and divine will, which places her at the mercy of patriarchy on both levels. Modern eyes place too much emphasis on the negative aspect of the word ‘victim’, and the attempt to empower Leda with sexual freedom by appropriating her rape misses the point. As modern revisions show, Leda’s story is wider than the myth, it can encompass much of the female experience. Leda did fall pregnant with both her husband and Zeus’s children the night of her rape. But it was her divine child, Helen, whose beauty started the Trojan war, a child born in violence, who endured violence, and who sometimes ends in violence, encompassing the fate of of so many of her sisters.

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths: The Complete Edition, Penguin Books 1992 pp. 125-126 ↩

- Sword, Helen, ”Leda and the Modernists,” PMLA, Vol. 107, No. 2, 1992, pp. 306 ↩

- H.D., “Leda” Poetry Foundation ↩

- Debo, Annette, ‘H.D’s American Landscape: The Power and Permanence of Place, South Atlantic Review, Vol 69, No 3/4(Fall 2004) pp. 4 ↩

- Rainey ‘Canon, Gender, and Text: The Case of H.D.’ College Literature, Vol. 18, No. 3, Teaching Minority Literatures (Oct., 1991), pp. 115 ↩

- Graves, Robert, “Leda” in Kossman, Nina, (ed) Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths, Oxford University Press 2001 pp. 16 ↩

- Bardwell, W.C., “The Rapist in “Leda and the Swan”, South Atlantic Bulletin, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Jan., 1977), pp. 63 ↩

- Sword, ‘Leda and the Modernists’ pp. 307 ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Yeats, William Butler, “Leda and the Swan” in Kossman, Nina, (ed) Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths, Oxford University Press 2001 pp. 17 ↩

- Neigh, Janet, “Reading from the Drop: Poetics of Identification and Yeats’ ‘Leda and the Swan,’” Journal of Modern Literature Vol. 29, No. 4 (Summer, 2006), pp. 149 ↩

- Lawrence, D.H., ‘Leda’ in Kossman, Nina, (ed) Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths, Oxford University Press 2001 pp. 16-17 ↩

- Sword “Leda and the Modernists” pp. 312 ↩

- Rilke, Rainer Maria, “Leda” in Kossman, Nina, (ed) Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths, Oxford University Press 2001 pp. 16 ↩

- Sword”Leda and the Modernists,”pp. 306 ↩

- Neigh, Janet, “Reading from the Drop’ pp. 149 ↩

- Clifton, Lucille, “Leda” in Kossman, Nina, (ed) Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths, Oxford University Press 2001 pp. 18 ↩

- Kossman, Nina, “Leda” in Kossman, Nina, (ed) Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths, Oxford University Press 2001 pp. 18 ↩

- Van Duyn, Mona, “Leda” in Kossman, Nina, (ed) Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths, Oxford University Press 2001 pp. 17 ↩

- Bentley, Barbara, “Living Next to Leda” in Kossman, Nina, (ed) Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths, Oxford University Press 2001 pp. 19 ↩