She was the daughter of one of the most powerful men of the Middle Ages, a Princess of Lancaster by the age of fourteen, a widow at fifteen, and a royal Duchess of York by the age of sixteen. And just over a decade later, Anne Neville became the Queen of England. She remains one of the most elusive women in history. Was Anne Neville truly a hapless victim in the political games of the Wars of the Roses, or did she have ambitions of her own? Amy Licence joined us for a fresh look at Anne Neville, Anne the survivor, the wife, the mother and the woman behind the throne of the most notorious King of England.

It seems incredible that Anne Neville was married to Prince Edward of Lancaster and King Richard III, yet she remains one of our most elusive Queens. Was it difficult to research Anne considering the lack of contemporary accounts?

Very difficult indeed, there was so little surviving and because of this, so many myths had arisen in literature and film. So I had to strip back to what was known, which is not much, then consider what reasonably might be inferred and start from there.

Rather than cast Anne as the unwilling victim in her first marriage you argue that her time as a Lancaster Princess may have shaped her later ambitions. Could we speculate that her time with her mother-in-law Queen Margaret of Anjou, a powerful and independent woman, had some influence on her?

I think it is very likely. As Warwick’s daughter, Anne knew the destiny to which she had been raised; a dynastic match was always on the cards for her, it was just a question of with whom. There is no reason to suspect that Anne wasn’t ambitious; fourteen year old girls can be very focused and driven as I recall. Much has been made of Anne marrying into the family of her former enemy, Margaret, but there were many alliances made that crossed the boundaries of prior rivalries and hatreds. Anne’s marriage to Edward made her Princess of Wales and, for a period of around nine months, she lived closely with Margaret, when she was planning her return to England and the dramatic events that followed. Anne was a witness to all that. However, I do think it equally likely that Anne learned by negative example from Margaret, that she used her as a model for good and bad qualities. For the decade after marrying Richard, Anne doesn’t seem to have been particularly ambitious and perhaps, having seen Margaret’s troubles, she was content to live quietly. Once there was a chance for the throne though, she may have recalled the ex-Queen’s swift and decisive action, so I think the influence was formative yet selective.

Anne’s situation after her husband’s death was desperate, her father and father-in-law were also dead, her mother-in-law imprisoned and her mother fled to sanctuary. Her sister Isabel and her husband were keeping her captive and trying to cheat her out of her inheritance, how frightening must all this have been to a fourteen year-old girl?

Anne was in a state of limbo after Tewkesbury. She would have been grieving the losses of her husband and father but yet, she was aware that women were not treated in the same way as man during these conflicts. You only need to look at the “punishments” meted out to Margaret Beaufort to see what women could get away with by virtue of their gender. Anne was brought before Edward IV after Tewkesbury but this was her old family friend, whom she had known as a child. Regardless of the way her father had turned against him, Edward was unlikely to react with severity to a young girl in her situation and very quickly, she was released into the custody of her sister. From then, the situation opened up a new chapter for Anne; she could try and make a new marriage and that would change her fortunes again. We really do have to think about women making career marriages then, like Margaret Beaufort did and, as unsentimental as it sounds, widowhood was also an opportunity. It seems likely that Clarence was unwilling to let her remarry but the extent of Isabel’s involvement and her relationship with Anne at that point is not clear by any means.

Is there any real case for the claim that Richard abducted Anne against her will? After all it seems the plans were made carefully between them, and as you stated, marrying the King’s brother was her best chance of securing her rightful inheritance.

There is no case to believe this, it goes against what was actually in Anne’s best interests at the time. The Croyland Chronicle contains the story of her being hidden as a kitchen maid by George, but there is no other contemporary corroboration that Anne did not welcome the match. It was definitely in her interests to marry Richard, on a financial and social level. The alternative was to remain in Clarence’s household at an age when she was ready to be remarried and perhaps to be matched with a husband of his choice. She may well have taken an active role in negotiating with Richard and after she left Clarence’s property, she went into sanctuary. If she had any doubts about marrying Richard, she was in a safe, independent place and he would not have been able to insist on the marriage going ahead. This suggests to me that Richard helped her get there, as it was actually Clarence who opposed the match, which divided the Warwick daughters’ inheritance. Richard could help Anne achieve what was rightfully hers and she could bring him her father’s northern supporters; it appears to have been a mutually beneficial arrangement.

Do you think the lack of contemporary accounts of Anne may have fuelled the speculation that her marriage was an unhappy one or is it more to do with the blackening of Richard’s name in general?

I think this stems from the rumours that circulated about her death and her childbearing record. There is no evidence to suggest an unhappy marriage and the correlation that is often cited, between having a large family and the closeness of a couple, is an oversimplification. Richard’s supposed cruelty towards Anne has stemmed from depictions such as Shakespeare’s and references in chronicles to rumours that he supposedly poisoned her, which were very useful for Tudor writers. The few examples we do have of their married life show them working together in terms of local administration and religion but then, as we must be aware, this would be the expectation of a married couple of their rank. No one knows what goes on behind closed doors, and then, as now, only two people ever know what a particular marriage is like.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

You said that Anne and Richard’s only son Edward had been a bond, which broke them with his death. Aside from the rumours of his plans to marry his niece, it was said he was considering a divorce, if Anne’s health had not declined so suddenly do you think he would have tried to put her aside so he could remarry and try for another heir?

It is very difficult to speculate about this one. We do know that the ambassadors for the proposed Portuguese match departed from court only six days after Anne died, which suggest Richard was already thinking about the possibility of fathering more heirs during her lifetime. I think we have to separate out Richard the man from Richard the king; he may have still loved Anne on a personal level but remaining married to her would have jeopardised his security on the throne. A king without an heir was vulnerable and as she grew weaker in the spring of 1485, it became clear that she would bear no more children. It would have been essential to the king to have a son, so it is entirely likely that he may have considered putting Anne aside. He is reputed to have muttered something to this effect in the summer of 1484 to Archbishop Rotherham, who claims he also regretted Anne’s unfruitfulness in front of various noblemen, although it can’t be verified. This doesn’t mean he didn’t care for her; in fact, it was probably heartbreaking for them both.

Although it may sound improbable, do you think that Anne’s death may have contributed somewhat to Richard’s downfall, and he may have perhaps kept the loyalty of his people had they not been speculating about him being responsible for her death?

I don’t think that is improbable, quite the opposite; there were rumours to that effect which can’t have helped his cause. After the Elizabeth of York scandal, Catesby and Ratcliffe warned Richard that the north would rise up against him if he married his niece, in the belief that he had poisoned Anne in order to do so. The fact that Richard was forced to make a public declaration to the contrary shows that he took the threat of these rumours seriously. In an era of imperfect communication, such tales could take a hold of the popular imagination and sway people’s thinking, especially in areas that were loyal to Warwick’s name. I think Anne’s death was a major personal blow to Richard but it was damaging on a wider scale for the potential it gave his enemies to exploit the situation.

Visit Amy Licence at His Story Her Story

Writing about medieval and Tudor history, with a particular interest in women’s lives and experiences. I’m the author of four books and have also written for The Guardian, BBC History website, The New Statesman, The Huffington Post, The English Review and The London Magazine. I appeared in a BBC2 documentary “The Real White Queen and her Rivals” and have been interviewed numerous times live on radio. I’ve also been shortlisted twice for the Asham Award for women’s short fiction. @PrufrocksPeach

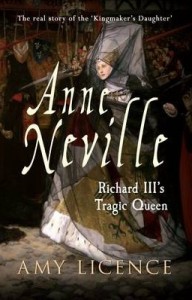

Anne Neville: Richard III’s Tragic Queen by Amy Licence. Published by Amberley Publishing May 2013

Buy Anne Neville: Richard III’s Tragic Queen.

Shakespeare’s enduring image of Anne is one of bitterness and sorrow. She curses the killer of her husband and father, before succumbing to his marriage proposal, bringing to herself a terrible legacy of grief and suffering an untimely death. Was Anne a passive victim? Did she really jump into bed with the enemy?