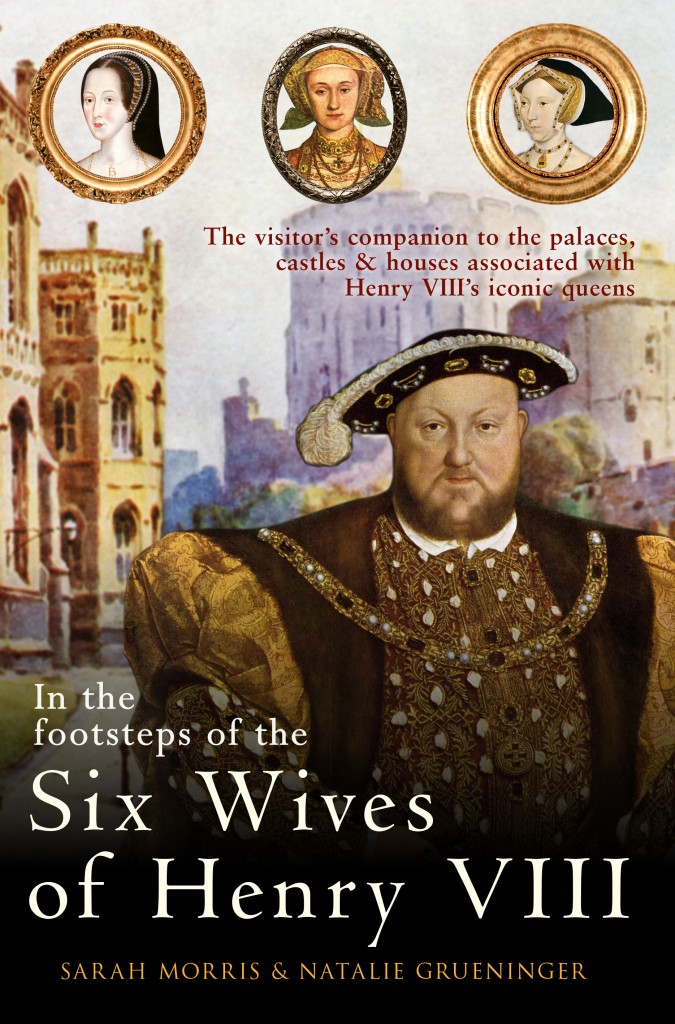

In 2014 Natalie Grueninger and Sarah Morris took us on a unique journey through the life of Queen Anne Boleyn, exploring the historical places associated with Anne and sharing their experiences so Tudor enthusiasts could follow in Anne’s footsteps. Now Natalie and Sarah have returned with a new perspective on Henry’s Tudor consorts, through the buildings connected to them, and that connected them to each other. Natalie and Sarah join us today to discuss their latest book In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII.

How did you decide on locations for this book?

Natalie: We decided to concentrate on a handful of the most interesting or revealing locations connected to each of Henry’s wives, and where possible, focus on locations that are still standing and can be visited by the Tudor enthusiast. Unlike our first book, In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, which is a comprehensive guide to historic sites associated with Anne, this book is more ‘a best of’.

In deciding on locations for our book, we also tried to pick places that would allow us to shed light on the early years of each queen consort, in particular those of Katherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves.

The first part of the book is on principal royal residences. You’ve noted major events that happened to each of Henry VIII’s consorts in these palaces. It felt a bit eerie reading about all of these important moments in these women’s lives, only connected by bricks and mortar. How did it feel when you were looking at everything that had happened behind those walls?

Natalie: It was intriguing, I suppose, to come to see that so much of the personal drama of Henry VIII’s reign played out at a handful of royal residences, and to discover just how intertwined the lives of these women were. Over the years, the wives were replaced but the buildings, for the most part, remained the same – silent witnesses to all the upheaval and politicking. Just imagine all that a place like Hampton Court, Whitehall or Greenwich witnessed during the sixteenth century.

Henry tried to remove all references to his former consorts from the decorative elements of his palaces, however, their memories were imprinted in the very fabric of the buildings. No amount of refurbishment could change that. Just think that in the same chamber built for Katherine of Aragon at Hampton Court Palace, Anne Boleyn very likely gave birth to a stillborn child in the summer of 1534. This is the very same room in which Jane Seymour would later give birth to Prince Edward, and eventually die.

Try as he might have to completely forget certain events, in the quiet moments, especially when his health was failing him, the past must have descended all around Henry.

Which of the principal royal residences are most important to you as writers?

Natalie: I feel most connected to Hampton Court Palace. Of course this has to do with the fact that more survives of HCP than of any other Tudor palace. I can go there today and see things that the Tudors saw and touch things that the Tudors touched – utterly amazing. I’m sure, though, that if Greenwich or Whitehall were still standing, I’d have a difficult time choosing a favourite!

It was lovely to read about Katherine of Aragon’s childhood residences, which do you think have the most connection with her young life?

Natalie: This is difficult to answer because Katherine’s family was constantly on the move, however, I think that the Alhambra in Andalusia, a sprawling and breathtaking palace and fortress complex built by the Nasrid kings in the thirteenth century, is particularly important to Katherine’s story because it’s where she lived for much of the last two years of her life in Spain. From within the Alhambra’s rust-coloured walls, Katherine wrote love letters to her betrothed, Prince Arthur, and prepared for her journey to England.

Years later, when Katherine fulfilled her destiny of becoming England’s queen, she adopted the pomegranate as her personal heraldic symbol. The fruit, with its abundance of reddish seeds, had long been a symbol of fertility, but it was also the symbol of Granada. It was a city that Katherine saw for the last time when she was 15 years old but carried with her in her heart until her dying day.

Buckden was not one of Katherine’s happier residences, why do you think the village of Buckden feels so close to Katherine today?

Sarah: Emotional loyalties run deep and although countless generations have come and gone at Buckden, that soul connection to Katherine endures. The feeling is palpable for those who wish to follow in her footsteps. Certainly, those locals with an interest in their village’s history speak about her with affection and the deepest respect, even to this day.

Katherine was, of course, always a popular queen with the English, despite her Spanish heritage. But this bond was forged before England’s great rivalry with Spain. One historian has written that the fresh faced princess who arrived in England reminded the people of her English ancestry with her fair hair and blue eyes. Despite Katherine’s inability to provide the country with a male heir, she remained a dignified queen and loyal wife. There was little anyone could do to dislodge her halo. Henry and Anne Boleyn’s perceived ill treatment of Katherine only served to deepen people’s sympathy for the discarded queen.

We must imagine Buckden in the sixteenth century, a tiny village lying adjacent to the Great North Road, at some distance from London. The impressive palace of Buckden would have been the centre of village life. It must have been the event of the century to have the king’s discarded wife turn up on their doorstep! One can only imagine how she would have been the ‘talk of the town’. Far away from the intrigues of London, it is not hard to see how the village folk rallied around the ageing queen, a picture of piety and devotion. In a time when most people never even saw the reigning monarch, here was Katherine in the flesh. At this point, it was no longer just gossip about the ‘King’s Great Matter’, this was personal. Katherine became their queen and somehow that loyalty has remained imprinted on the fabric of the village, even though her contemporaries are long gone.

You have found a few new residences that Anne Boleyn visited, can you tell us a bit about them?

Natalie: Yes, we’ve included four new locations associated with Anne Boleyn: Haseley Court, Buckingham, Hunsdon House and Chertsey Abbey. In 1529, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn stayed at Haseley for two days while en route to Grafton Regis in Northamptonshire. Identifying the exact house in which they lodged was not easy, as at the time Haseley was divided into four: Latchford, Rycote, Great Haseley and Little Haseley, and all possessed some form of manor house. However, after examining all available evidence, we concluded that the royal couple most likely stayed in Little Haseley, at the home of Sir William Barentyne.

Like Haseley, Buckingham proved a less than straightforward location to research. We know for certain that Henry and Anne overnighted in Buckingham on 9 September and again on 24 September 1529, but where exactly they stayed was not recorded in the household accounts. Again, after much investigation, we concluded that the available evidence pointed to the couple having lodged at the home of Henry Carey, the son of William Carey and Mary Boleyn, who was just three at the time of the visit.

Hunsdon House, on the other hand, was less of a mystery. The house, where the court stayed on a number of occasions, was luxurious and grand, and one of the most important residences of fifteenth century England, as reflected by its string of illustrious owners: Edward IV, Richard III, Sir William Stanley and Margaret Beaufort. After Margaret’s death, the house passed to Thomas Howard on his elevation to the dukedom of Norfolk, and then to his son and heir, Thomas. Eventually, it fell into the hands of Henry VIII, who transformed Hunsdon into a house of palatial proportions.

The last of the ‘new’ Anne Boleyn locations is Chertsey Abbey. This was once one of the greatest abbey’s in England, rivalling the likes of Reading and Glastonbury. Both Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn lodged within its ancient walls. Today very little survives of this once great monastic complex.

There is a lot of mythology surrounding Wolf Hall, which dates well before the novel or television series named after it. Why do you think people are so fascinated by it?

Sarah: Well, I think you have nailed it in the question; it is the legend of the place that intrigues so much. That legend tells us that it was at Wolf Hall that Henry first laid eyes on Jane. I don’t believe that is true, by the way. Jane had been serving at court for some years before that fateful visit. However, it may well be that it was at Wolf Hall that there was some shift in attitude toward the Seymour’s eldest daughter. If that legend is true, then it is here that we date the beginning of Anne’s downfall, the point at which Jane finally wrestled away Henry’s dying affections from the woman who had once so overpowered the king with her charms – Anne Boleyn. Furthermore, it seems incredible that ‘plain Jane’ managed to dislodge a woman of such potency at all. After all, Anne was a force of nature compared to Jane’s apparently insipid character.

And yet was she so passive? She was certainly very different, but who was she really? I always feel Jane remains more elusive than the dominating characters of Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn or Katherine Parr, all of whom left strong legacies of their characters. So we have to look a little harder with Jane, and it was at Wolf Hall, during Jane’s early life, that we can find more clues about the genesis of the woman she would become. Firstly, it was whilst researching Wolf Hall and its remoteness, (once sited on the edge of the Severnake Forest in the heart of the Wiltshire countryside), that I began to appreciate the parochial nature of Jane’s isolated upbringing. I was also intrigued by the obvious similarities in character between descriptions of Jane’s mother, Margery Wentworth, as a young woman and Jane as queen. It seemed to me she was very much fashioned from the same clay. Everything about Jane at Wolf Hall speaks of a traditional, conservative upbringing. It is the ability of these locations to fashion a picture of the early forces that melds a person’s character which I find most intriguing. However, if you think Wolf Hall is beguiling from the legend alone then think again; I was surprised to find how much the energy of the place drew me in when I visited, even though very little remains. It is indeed as if the place has a story to be told and refuses to pass into obscurity.

Where did you feel the most connection with Jane Seymour?

Sarah: Actually, it was at a place that I strongly suspect most people have never heard of – Chester Place – a grand mansion that once stood in the footprint of the present day Somerset House in London. There is not one single brick of Chester Place remaining above ground to this day. In its heyday, it must have been a place of some significance though, for it was here that the ambitious Seymours first established their permanent base in London. Located adjacent to the Thames, just one mile from Whitehall, this prestigious location had previously been home to the Bishop of Chester. However, as the power of the clergy ebbed away during the latter part of Henry’s reign, new men at court, epitomised by the ambitious Edward Seymour, gained increasing influence with the king. A number of similar properties along the Strand were wrested away from their respective bishoprics and gifted to powerful families of the day whose cache was in the ascendency. Chester Place was one such location, with Edward and his heavily pregnant wife, Anne Stanhope, moving in on 14 February 1537.

I loved this place for a number of reasons. Firstly, I knew nothing about it when I first starting researching locations associated with Jane. In general, lost palaces and houses are amongst the most fascinating to me, often because knowledge about the buildings and events which took place there has been lost along with their physical demise. I believe this is true of Chester Place. It is like setting out on a veritable treasure hunt – one where you have no idea what you will uncover!

In this instance, we knew that this was one of the few recorded locations visited by Jane as queen. What made it all the more special was the fact that the visit was in relation to a private family event, (which is rarely commented upon), and because of the unexpected information about the event uncovered in a contemporary source – the original Seymour Papers, stored today at Longleat House.

Jane was to be godmother at the christening of a girl named in the queen’s honour. It was particularly thrilling to uncover the true identity of this child in the aforementioned documents as almost all (if not all), official sources cite that the child was male and named Edward. It was one unexpected myth that we were able to debunk.

This high society christening was blessed not only by the presence of the queen but her step daughter, Princess Mary, and soon-to-be brother in law, Thomas Cromwell, both of whom were also acting as god parents. The Seymour Papers opened up tantalising insights into the layout of the house and the preparations for the christening. Combining this with research around the sixteenth century rite of baptism, I felt that I was able to get up close and personal at a moment when Jane was at her zenith; just pregnant herself, and one hopes enjoying the thought of finally holding her own child in her arms, it is at Chester Place that we catch a rare glimpse of the private life of the enigmatic Jane Seymour.

You made some really interesting discoveries about Anne of Cleves’ early residences and the set of heraldic panels. Do you feel you know a lot more about Anne now?

Sarah: In comparison with some of Henry’s other, more vocal wives, it is easy to brush over Anne of Cleves as a woman of little interest. I think many people will empathise with this notion. For me personally, having spent so much of my time previously writing about Anne Boleyn, I confess that when I started researching Anne of Cleves for the latest book I did not feel as if I knew her at all well. So in many ways, this was an exciting undertaking. I wondered just who I would discover and whether my opinions on ‘the Flanders’s Mare’ would change. However, I also approached this part of the book with some trepidation. I knew that in order to unlock the secrets of Anne’s early years, I would need a considerable amount of help as neither Natalie nor I can speak German or Dutch, both languages relevant to Anne’s time prior to her arrival in England. Thankfully, an abundance of generosity from all sorts of people along the way helped me piece together the story of the first twenty-four years of her life.

I know I have spoken of this before, but after having written two ‘In the Footsteps’ books, I feel very strongly now that if you want to truly understand each of Henry’s queens, the place to look is in those locations that nurtured them as children. Delving deeply into the social and cultural milieu which existed in these places at the time, gives a rich picture of the forces that must have influenced their later personalities; the events that took place, the customs of court or family life, the people and ideas they came in contact with, and even the type of buildings they lived in all provide important clues. So, for example, my research really impressed upon me the predominantly female environment in which Anne was raised; the close and loving relationship between her parents; the strict and rather restrained etiquette of the German, ducal court and the limited education of women in academic or outdoor pursuits. Anne emerged from all this as a kind, loving person, eager to please. I came to know her as a gentle soul with a good heart. It is difficult to imagine her harming anyone. I learnt to appreciate her values of subtlety, purity and modesty which were so venerated in women in her homeland at the time. It was also painfully obvious how ill-equipped she was for life as queen consort at the English court – she could not hunt, hawk, dance or sing, for example. All attributes considered essential in an aristocratic English lady at the time.

So yes, I do feel much closer to Anne, and I have a tremendously soft spot for her. She is a woman of many worthy qualities and I hope those who have read, or will read, the book will come to appreciate them as much as I have.

What do you think the heraldic panels tell us about Anne of Cleves?

Sarah: The panels are unique. It was incredible to uncover their true origins and such a privilege to know that these were once commissioned by Anne herself to adorn a high status room in one of her dower properties; the most likely contender being the King’s Manor at Dartford. As Jonathan Foyle (the architectural historian who worked closely with us around unlocking the mystery of the panels) stated, nothing of the domestic environment of the royal household of the time was thought to have survived – until now. They represent a new national treasure.

The carvings themselves are of exquisite quality; they are a statement of status and affluence. The style of the carving is ‘counter-reformation classicism’, which means they were carved at some point during the reign of Queen Mary (1553-1558). Whilst we have written extensively about 150 or so Tudor buildings over the course of the two books, the opportunity to get so close to a set of artefacts that are so directly related to one of our protagonists is rare. It gives us a ‘living’ insight into the interior of one of Anne’s palaces, the panels most likely decorated a long gallery or closet. What it reaffirms is that Anne was a wealthy woman, who despite some financial difficulties managed to maintain a lifestyle of privilege right up until the end of her life.

We tend to focus on Catherine Howard’s unhappy demise rather than her reign. What are some of the happier residences connected with the young queen?

I know that for many, Hampton Court Palace conjures up images of Catherine’s screaming spectre, however, it was within the palace’s russet-coloured walls that Catherine spent many happy days, including her one and only Christmas and New Year as queen, when her discarded predecessor, Anne of Cleves, publically acknowledged her. For the first six months of their marriage, a besotted Henry VIII showered his young bride with lavish gifts, including ‘a jesus of gold containing 32 diamonds’, ‘a purse of gold enamelled red, containing 8 diamonds set in goldsmith’s work…’ and a stunning necklace dripping with diamonds, rubies and pearls.

In August the couple set off on a royal progress from Windsor, stopping at Reading, Ewelme, Notley, Buckingham and Grafton. September was spent largely at Ampthill and in October the newlyweds visited Dunstable, St Alban’s and The More, before returning to Windsor on 20 October. How exactly Catherine passed her time while on progress is unknown, however, the French ambassador Charles de Marillac reported in September 1540 that there was nothing being spoken of at court, except for ‘the chase, and the banquets to the new Queen’, so she was clearly enjoying herself! In November, he wrote that ‘the new Queen has completely acquired the King’s grace, and the other [Anne of Cleves] is no more spoken of than if she were dead’. These were indeed happy times for Queen Catherine.

Katherine Parr had quite a full life before becoming a queen. What do some of the earlier residences connected with Katherine reveal about her?

Sarah: The most striking thing to me about Katherine Parr’s earliest years is the degree of stability she experienced as a child. Katherine moved from London to the verdant Hertfordshire countryside when she was about 5 years old. There, the family took up residence at Rye House. Although extremely modest in size compared to the grand palaces she would later occupy as queen, it was avant-garde in terms of the fabric from which it was made, being one of the earliest examples of brickwork in England.

Katherine would live at Rye for the next twelve years, until she left to become the wife of Edward Borough of Gainsborough. Until that point, it is clear that she lived a life of privileged domesticity. Unlike Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn or Anne of Cleves there was no itinerant court to follow. Katherine, her siblings and cousins (who were educated alongside her in the schoolroom at Rye) must have known every nook and cranny of the building, every meadow and glade that surrounded it. Unlike Catherine Howard, Mistress Parr was the benefactor of a strong parental presence throughout her early years. While Katherine unfortunately lost her father soon after moving to Hertfordshire, it seems that Lady Parr was determined to provide this stability and continuity for her children, returning periodically from court and her role as lady in waiting to Catherine of Aragon to lavish love upon all the Parr children. The strength of the bond she created is evident in the close relationship that Katherine maintained with her mother until Lady Parr’s death in 1531. In this I see the origins of Katherine’s ability to nurture strong, loving relationships that surely would serve her well in both her second and third marriages. It seems to me that her mature, grounded adult character in every way was a product of all these early influences.

All of this would have had a tremendous influence on Katherine’s character, but we cannot overlook the final piece of the jigsaw. Katherine received the most advanced education available to girls of the time. Following on from Thomas More’s example with his own children, the humanist curriculum at Rye was diverse, including several languages, probably mathematics and medical lore, rounded off with training in the noble courtly pursuits of hunting and hawking. Katherine was an intellectual tour de force for a woman of her time, and all this we can see nurtured in the school room at Rye.

While Katherine’s intellect and passion for religious reform are well-known, her role as a mother to her step-children, two of whom had lived in great instability, is often underrated. Which residence do you connect with Katherine as a mother?

Sarah: For me, that has to be Snape Castle in North Yorkshire. Katherine was twenty two years old when she married for the second time. Her new husband was Lord Latimer of Snape, a man who was twice her age. He had two children from a previous marriage; Margaret and John, who were nine and fourteen years old, respectively, at the time of Katherine’s arrival. Of course, Katherine would become step mother to three royal children following her marriage to Henry in 1543, but this was her first taste of motherhood and it turned out to be a difficult and challenging training ground.

We know something of these experiences on account of Katherine’s later writing, where she describes the difficult and selfish nature of ‘younglings’. This is clearly a reference to the experiences with her stepson, John, who proved to be a challenging teenager. As an adult he would be charged with rape and murder. Quite in contrast was her relationship with Margaret, the younger of the two siblings, who obviously relished a mother-figure entering her life; the two would remain close until Margaret’s death at Greenwich in 1546.

Yet forging a relationship with her step children was not the only challenge for Katherine at Snape. It was here that Katherine found herself alone, as guardian of the two children and in the midst of the uprising which would become known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. Katherine, herself only in her mid twenties, was taken hostage along with Margaret and John by a group of angry Northern rebels, insisting that Lord Latimer show himself and his allegiance to the cause. Latimer had to hurry north from London, fearing for his family and property. It must have been a relief to see her husband arrive at the castle gates. Thankfully, there is no record that the family came to any harm.

So what new projects are on the horizon?

Natalie: I’m currently working on two books for The History Press that will be published in the UK in 2017. The first is a guide to historic sites in London, associated with the Tudors, provisionally entitled ‘Discovering Tudor London’, and the other is a colouring book for adults inspired by the ever-fascinating Tudor dynasty, called ‘Colouring History – The Tudors’. The latter is a collaboration with a friend and talented illustrator, Kathryn Holeman.

Sarah: I am taking some time away from history related projects at the moment to concentrate on my ‘other life’ in leadership development. I do have the next book in mind – and when the time is right, I’d very much like to write it. However, there are no immediate plans to get that project underway.

In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII is available now from:

Free Shipping Worldwide from Book Depository

This guidebook takes a fresh perspective on the tale of Henry VIII’s six wives, by taking you on a journey through a selection of manors, castles, and palaces that played host to Henry’s unforgettable queens. Explore the Alhambra Palace in Spain, childhood home of Katherine of Aragon; stand in the very room at Acton Court, where Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII publicly dined; walk the cobbled grounds of Hampton Court Palace, which bore witness to both triumph and tragedy for Jane Seymour; visit Dusseldorf in Germany, birthplace of Anne of Cleves; travel to Gainsborough Old Hall in Lincolnshire, where Henry VIII and Catherine Howard rested on their way to York in 1541 and wander the picturesque gardens and panelled rooms of Sizergh Castle in Cumbria, where Katherine Parr spent time in mourning, after the death of her first husband.

Each location is covered by an accessible and informative narrative, which unearths the untold tales and documents the artifacts, as well as providing practical visitor information based on our first-hand experiences of visiting each site. Accompanied by an extensive range of images, including family trees, maps, photographs and sketches, this book brings you closer than ever before to the women behind the legends, as it takes you on your own personal and illuminating journey in the footsteps of the six wives of Henry VIII.

Natalie Grueninger

Natalie Grueninger is a researcher, writer and educator, who lives in Sydney with her husband and two children.

Natalie Grueninger is a researcher, writer and educator, who lives in Sydney with her husband and two children.

She graduated from The University of NSW in 1998 with a Bachelor of Arts, with majors in English and Spanish and Latin American Studies and received her Bachelor of Teaching from The University of Sydney in 2006.

Natalie has been working in public education since 2006 and is passionate about making learning engaging and accessible for all children.

In 2009 she created On the Tudor Trail (www.onthetudortrail.com), a website dedicated to documenting historic sites and buildings associated with Anne Boleyn and sharing information about the life and times of Henry VIII’s second wife. Natalie is fascinated by all aspects of life in Tudor England and has spent many years researching this period.

Her first non-fiction book, co-authored with Sarah Morris, In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, was published by Amberley Publishing and released in the UK in late 2013. Natalie and Sarah have just finished the second book in the series, In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII, due for publication in the UK on 15 March 2016 and on Amazon US on 19 May 2016.

You’ll find Natalie on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Dr Sarah A. Morris

Sarah is a creative soul, as well as an eternal optimist who generally prepares for the worst! She is an advocate of following the heart’s deepest desire as a means to finding peace and happiness. To this end, her writing is a creative expression of her joy of both learning and educating.

Sarah is a creative soul, as well as an eternal optimist who generally prepares for the worst! She is an advocate of following the heart’s deepest desire as a means to finding peace and happiness. To this end, her writing is a creative expression of her joy of both learning and educating.

Drawn by an inexplicable need to write down the story of Anne Boleyn’s innocence, she published the first volume of her debut novel, Le Temps Viendra: a novel of Anne Boleyn in 2012; the second volume followed in 2013. That same year, her first non-fiction book, co-authored with Natalie Grueninger called, In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, was also published. Hopelessly swept away by an enduring passion for Tudor history and its buildings, her latest book, the second of the In the Footsteps series entitled, In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII, is due to be published by Amberley Publishing in the UK on 15th March 2016 and in the US on 19th May.

She lives in rural Oxfordshire with her beloved dog and travelling companion, Milly.

You’ll find Sarah at www.letempsviendra.co.uk, or via her blog, This Sceptred Isle https://letempsviendra.wordpress.com/.