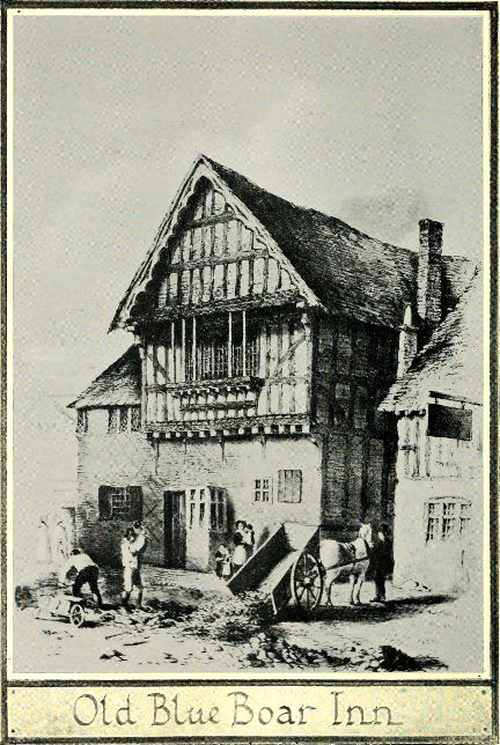

There is a popular legend that, prior to the battle of Bosworth, King Richard III spent the night of 20-21 August (and possibly also the night of 19-20 August) in Leicester, at an inn, later known as the ‘Blue Boar’, but which at that time may have been called the ‘White Boar’ in Northgate Street, a fine timbered building in the town centre. The implication behind this story appears to be that, since the inn bore Richard’s own personal badge as its sign, it may have had some pre-existing connection with the king.

It is true that some medieval inns did have established connections with aristocratic patrons, being either owned by them and run by a tenant ‘landlord’ on their behalf, or enjoying the patronage of a particular nobleman on a regular basis. The present writer has previously researched such evidence in respect of Sir John, Lord Howard, later Duke of Norfolk. ‘We know, from his household accounts, where Howard stabled his horses when he and his entourage were in Colchester. The Bell, The Bull, The Hart and The Swan Inns are mentioned in this connection’.1

In addition:

When passing through Chelmsford, Howard and his emissaries tended to use inns on the southern outskirts of the town.2Of the Chelmsford inns known to have been used by Howard and his retinue, three, the Cock, the Lion and the (White) Hart were located at the southern end of the High Street, between the river Can and Springfield Road.3 These were not notably salubrious establishments. Robert Snell, landlord of the Cock in the 1470s was frequently in trouble for tipping refuse into the ‘Gullet’.4 Just across the road, Nicholas Hyde, the landlord of the Lion reportedly deposited forty cartloads of excrement in the river Can in 1482.5 The Angel, another inn used by the Howard retinue, was much nearer the town centre, in Tindal (or Conduit) Street.6 The other two Chelmsford inns mentioned in the Howard accounts, the Key and the Swan, remain unidentified. Either their existence was short-lived, or they must later have changed their names.7

However, except for the Lion in Chelmsford, there is no evidence that the inns in Colchester and Chelmsford sponsored by John Howard had names which echoed his heraldic symbols. Nor is there any evidence that Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III) sponsored inns in this way.

The claim that Leicester’s ‘Blue Boar’ inn (which unquestionably existed under that name in the sixteenth century) had previously been called ‘The White Boar’, but that its name was altered following Richard III’s defeat at the battle of Bosworth, is traceable as far back as John Speede.8 However, no contemporary evidence survives to substantiate the existence of a Leicester inn called the ‘White Boar’ in the fifteenth century. Even the earliest surviving mention of the Leicester inn under the name of ‘The Blue Boar’ dates only from the 1570s.

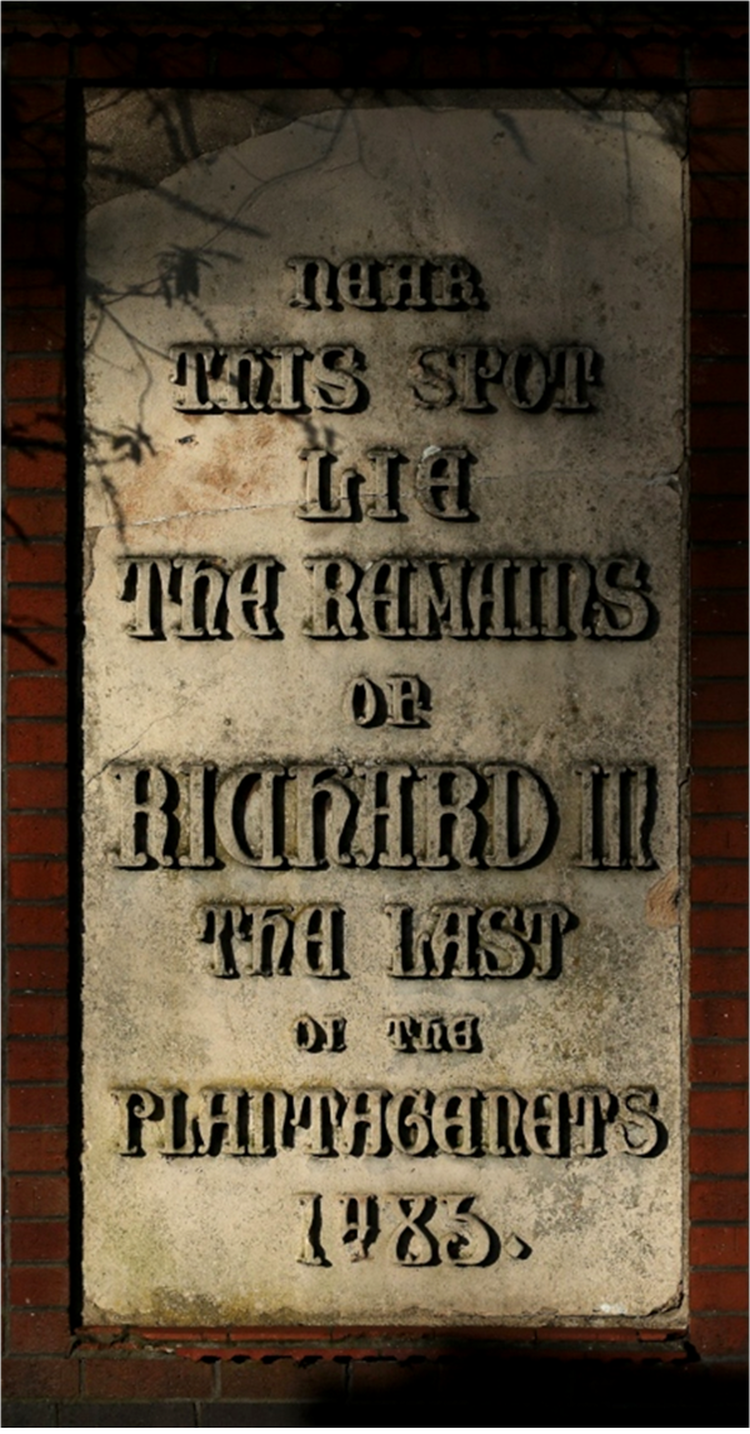

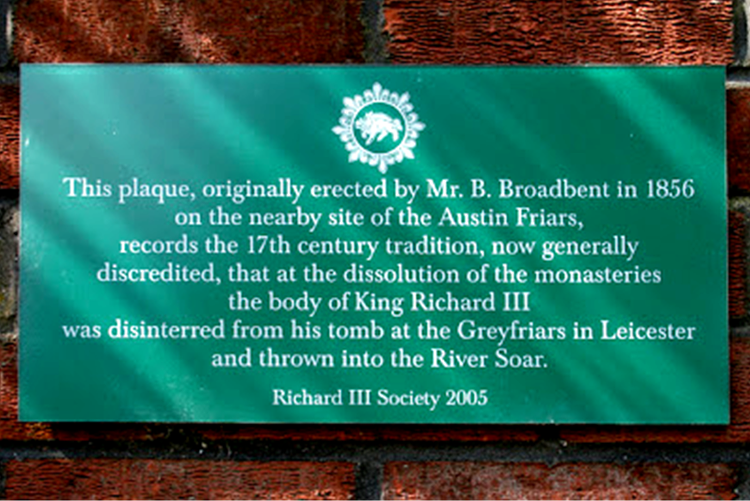

Significantly, John Speede is also the earliest surviving written source for the legend that Richard III’s body was dug up at the Dissolution and taken to the river Soar. Speede’s account said that the body was reburied under Bow Bridge. Later accounts changed the story, producing a claim that the bones had been thrown into the river. This legend was formally regarded as highly significant and credible in Leicester. In the nineteenth century it led to the erection of a large stone plaque near Bow Bridge, which states that Richard III’s remains lie somewhere nearby.

In the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century the story was reprinted on various occasions by the Leicester Mercury:

Richard was buried in a stone coffin in the chapel of the Grey Friars Fransiscan [sic] Abbey [sic], which was sited near the present cathedral. The defeated king was not allowed to rest in peace though. The story goes that Richard’s body was later dug up and hurled unceremoniously into the River Soar from Bow Bridge. But the story does not end there. Almost 400 years later in 1830, when foundations were being excavated for a new Bow Bridge, two skulls were found. One had a gash across the cranium. Later carbon dating proved the owner would have lived about 1500. Was this the skull of Richard III, the last King of England to lead his troops into battle?9

Legend has it that the king’s body was dug up from his tomb in Greyfriars, and flung in the Soar by an angry mob, fifty years after his death in 1485 on Bosworth Field. At least two skulls or sets of bones are said to belong to the king. One set was taken from a Leicester Museum in the 19th century and another is thought to be in the hands of a private collector.10

Although the research of the present writer disproved this story,11 leading to the granting to him of permission by Leicester City Council to erect – via the Richard III Society – a modern corrective-statement plaque beside the Victorian stone plaque near Bow Bridge, this obviously did not convince everybody in Leicester.

Thus in September 2012, when the remains which proved to be those of Richard III had been found on the Leicester Greyfriars site, Richard Buckley, leader of the ULAS team of archaeologists who had been employed by the Looking for Richard Project to carry out the excavation, once again stated, on his exhumation request form, that ‘Richard III … may subsequently have been exhumed and thrown into the nearby River Soar after the Dissolution in 1538’.12

Significantly, Leicester historians made specific connections between the traditional ‘body in the river’ story – which was definitively proved false in 2012-13 – and the traditional account of Richard III’s stay at the Boar Inn. For example, in respect of the first story, Billson wrote that ‘tradition has recorded that, when the monastery of the Grey Friars was dissolved, the remains of Richard the Third were taken from his tomb, and thrown over the Bow Bridge into the river Soar’.13 Regarding the second story, Billson’s account was as follows:

Passing down the ancient High Street on his tall white charger, [Richard III] is said to have drawn rein, before reaching the High Cross, at the Blue Boar Inn, a beautiful building, with a tall gable front and a projecting balcony of carved oak, which stood on the western side of the street, at the corner of the lane leading to the Hall of the Guild Merchant, and which was demolished about eighty-four years ago. Here, in the large front chamber, according to tradition, Richard spent that night; and a bedstead, on which he is supposed to have slept, became famous at the beginning of the 17th century as one of the curiosities of Leicester. The local tradition is unsupported by any authority, but it is not contrary to known facts. It has been asked why the King did not sleep at Leicester Castle, where he had stayed just two years before; but a campaigner, on the eve of a decisive battle, may have had several reasons for preferring to pass the one night in a less ostentatious place of sojourn. At any rate, there is no evidence of his having slept elsewhere. On this point Kelly made some very just remarks. ‘Whatever may have been the reason’, he wrote, ‘for the King’s sleeping at an Inn, as there is nothing beyond mere supposition to invalidate its truth, we confess that we believe in this, as we would in all local historical traditions not contradicted by positive evidence, from a conviction that no such tradition, although it may in process of time become exaggerated by oral transmission, is without some foundation of truth; and more especially one connected with so tragic an event as the last visit of Richard III, all the particulars connected with which must have made a deep and lasting impression on the minds of the inhabitants of the town, who would naturally transmit them to their descendants’.14

Despite the assertions of Billson and Kelly, it is, in fact, highly contentious whether Richard III really stayed at a ‘Boar’ inn (of any colour) in Leicester in August 1485. The story is rendered questionable by the lack of evidence for the existence of such an inn at the date in question, and by the fact that the king was assembling his army at the time. Much more significant, however, is the very solid evidence which indicates that Richard himself (both as Duke of Gloucester and as King), his predecessor and elder brother, Edward IV, and his second cousin and successor, Henry VII, all seem to have stayed at Leicester Castle on their recorded visits to the town.

Some modern authorities have asserted that Richard III would have been unable to stay at Leicester Castle in 1485 because the castle was falling apart. One recent account claims that ‘on his previous visits to Leicester, Richard had stayed in the Castle but by 1485 that was starting to fall into disrepair’.15 Yet this is at variance with other published accounts (see below). Also new evidence, comprising the regularity of royal visits during the previous twenty-five years, has now been assembled by the present writer. This argues strongly against the assertion that by 1485 Leicester Castle was in decay. The evidence will be presented in detail shortly.

The earliest surviving privy seal documents of Henry VII date from September 1485 (by which time he had left Leicester and reached London). Nevertheless, it seems probable that, following his victory at the battle of Bosworth, Richard III’s enemy and successor, Henry VII, also stayed at Leicester Castle. The new king had the body of his dead predecessor put on display in Leicester, and this seems to have been at the Church of Our Lady of the Newark, just by Leicester Castle. ‘The Newark’s enclosed situation and nearness to the castle, where he was staying, made it an ideal place for Henry Tudor to show his rival’s dead body’.16

‘There is little evidence of building activity at any of Henry VII’s houses during the first nine years after his accession’.17 However, the castles of ‘Bolingbroke, Clitheroe, Halton Lancaster, Leicester Knaresborough, Monmouth, Pickering, Tickhill and Tutbury owed their continued preservation chiefly to the fact that they were the administrative centre of the great estates belonging to the Duchy [of Lancaster]. … If, as at Hertford, Lancaster and Leicester, the castle stood in the county town, then its hall provided accommodation for the county court, and it is for judicial purposes that portions of the two latter castles have remained in use up to the present day’.18

Moreover, Billson states specifically that ‘the destruction of mediaeval Leicester began with the passing of the Plantagenets and the dismantling of Leicester Castle’. 19

The last authentic record of its occupation seems to be a letter written by Richard the Third to the King of France, which is dated August 18th, 1483, ‘from my Castle of Leicester’. In the reign of Henry VII it fell into disuse. When John Leland saw it, sometime about the year 1536, it had already lost its ancient pride. ‘The Castle’, he wrote, ‘standing near the West Bridge, is at this time a thing of small estimation’. Royal Commissioners, appointed by Henry VIII, reported that it was rapidly deteriorating; and, although a Constable of the Castle was nominated, little was done to prevent its decay. The only part preserved was the great Hall. The spacious yard of the Castle, which so many a time had been gay with the flower of England’s chivalry, began to be made use of as a pound for enclosing stray cattle and horses and swine. Thus, in the year 1533, some countrymen, who threatened that they would come into the town to trade there against the regulations, were informed by the Bailiff that, if they did so, their horses should be ‘set in the Castle’, and they themselves punished.20

Even so, in 1609 part of Leicester Castle was still ‘used by the Justices of Assise and for a dwelling house for the keeper’.21

The rival modern allegation that Leicester Castle was decaying in the second half of the fifteenth century is in marked contrast to the stories reported about another royal castle, not far away, at Nottingham.

In 1461 Edward of York was proclaimed King, and throughout the 22 years of his troubled reign the banner of the White Rose waved from the [Nottingham] Castle, towers. His adherents met within its precincts for many a merry revel or for solemn conclave, and went forth to many a fierce conflict from within the shadow of it’s [sic] ancient walls. For Edward IV had a great liking for Nottingham, and it was here that he first proclaimed himself King. He enlarged and beautified the Castle, carrying almost to completion the work of his predecessors, and made it his chief residence and military stronghold. In addition to the Norman fortress on the highest part of the plateau (the site of the present Art Museum), the whole of the space now known as the Castle Green formed at this time the inner ballium, surrounded by beautiful buildings, protected by a dry moat, with portcullis and drawbridge, with fantastically sculptured ‘beasts’ and ‘giants’ on the parapet, and all the recognized means of defence; in fact, it was now looked upon as one of the largest and most magnificent castles in the land, and a secure retreat in time of danger.

Edward’s love for the place was perhaps only exceeded by that of his brother Richard, who completed with loving care what little remained to be done at the time of Edward’s death. The great tower at the N.W. angle — ‘the most beautiful part and gallant building for lodging’, as Leland termed it — had been carried up for three storeys in stone, and Richard completed it by erecting ‘a loft of tymbre with round windows (i.e. bow windows) also of tymbre, to the proportion of the aforesaid windows of stone, “which were a good foundation for the new tymbre windows’.22

It might be assumed from this that the Yorkist kings stayed at Nottingham Castle far more often than they did at Leicester Castle. But in fact this was not the case, as can clearly be seen by comparing the present writer’s newly discovered evidence for the frequency of Edward IV’s stays at Leicester Castle (Appendix 1) with the same evidence for the frequency of his stays at Nottingham Castle (Appendix 2).

The main source for fifteenth century royal stays in Leicester Castle comprises the surviving privy seal documents at The National Archives. These show that from Thursday 8 April 1462 (the Thursday before Palm Sunday), King Edward IV was staying in Leicester. Moreover, from Monday 12 April the surviving sources state specifically that Edward was resident at Leicester Castle. He stayed at the castle over Easter and remained there until 7 July.23 Indeed, he may even have stayed there a day or two longer. At all events, the king seems to have spent about thirteen weeks (3 months) residing at Leicester Castle on this occasion. He was there again on Monday 7 May 1464. This was a much shorter visit. On this occasion Edward IV stayed at Leicester Castle for a week, until (and including) Monday 14 May.24 By 15 May he was in Nottingham. However, he returned briefly to Leicester in July.25

The king stayed at Leicester Castle again in August 1468. He had previously been staying at Fotheringhay Castle, but he had arrived at Leicester Castle by Wednesday 10 August, and he remained there for two weeks. He was still at Leicester Castle on 24 August, but by 25 August he had returned to Fotheringhay.26

Edward IV passed through Leicester again twice in 1470. There is no real evidence that he spent the night there on the first of these two occasions.27 However, he was apparently resident at Leicester Castle once again, probably for at least nine days, in July and August 1470. He arrived in Leicester by 28 July, and left shortly after 6 August.28 He also seems to have spent a short time in Leicester in March 1471, after his return to England from his exile in the Low Countries.29

In 1473 Edward IV was again expected to go to Leicester. According to Sir John Paston, ‘men sey the Qwyen with the Pryce shall come owt off Walys, and kepe thys Esterne with the Kyng at Leycetr’.30 Although Sir John expressed some doubts about this visit, about ten days later, he reported that the king was then riding towards Northampton, and stated once again that after Easter Edward would be spending a good deal of time in and around Leicester31 And this certainly appears to have been the case. Easter fell that year on Sunday 18 April. Edward was at Leicester Castle early in May 1473,32 and again towards the end of June and in the first two weeks of July.33

The king was also at Leicester Castle in March 1473/4,34 and again in 1476.35 The summary of Edward IV’s visits to Leicester is listed in Appendix 1 – Edward IV in Leicester (see below).

Although Edward is not recorded as having been at Leicester Castle after 1476, his younger brother, Richard, is reported to have stayed at Leicester Castle during his visits to or through the town as Duke of Gloucester.36 Later, as King of England, Richard III, spent three or four nights in Leicester in August 1483, and the evidence seems clear that on that occasion he stayed at Leicester Castle.37 He appears to have been in Leicester again on 22 and 23 October 1483,38 though on this occasion the castle is not specifically mentioned. During a brief en route visit in July 1484, Richard seems simply to have called briefly at Leicester Abbey, without spending the night in Leicester,39 and four months later he issued a privy seal warrant in the town of Leicester,40 but again there is no conclusive evidence that he spent the night there.

This brings us to August 1485, when Richard III spent probably two nights in Leicester. Given his and his elder brother’s previous accommodation on visits to Leicester, and the fact that the young king was in command of – and was co-ordinating the assembly of – his army, the logical assumption would appear to be that he stayed once again at Leicester Castle on the nights of 19 and 20 August, as did his rival and destroyer, Henry VII, on the nights of 22, 23 and 24 August. Since Leicester still retains surviving remains of its castle – while absolutely nothing remains of the Boar Inn – it seem curious that Leicester historians appear to prefer to reassert the alleged royal connection with the lost inn, which lacks any evidence, when they could instead commemorate the genuine and documentable association of Yorkist kings with Leicester Castle.

Appendices

Appendix 1 – Edward IV in Leicester

Appendix 2 – Edward IV on Nottingham

References

- J. Ashdown-Hill, Mediaeval Colchester’s Lost Landmarks, Derby 2009, pp. 145-46. ↩

- The route between London and Colchester did not necessitate a visit to Chelmsford town centre. One had only to pass through the hamlet of Moulsham, cross the bridge over the river Can, into the southern end of the High Street, and then, instead of continuing northwards towards the market place and the church (now Chelmsford Cathedral) one turned right, crossing the river Chelmer and taking the Colchester road via Springfield. ↩

- H. Grieve, The Sleepers and the Shadows, vol. 1, (Chelmsford: Essex County Council / Chelmsford Borough Council, 1988), p. 75. ↩

- The waterway which ran between the Can and the Chelmer. Snell’s widow persisted in the same offence, as did the new landlord, William Carr, who took over the premises in 1482. ↩

- Grieve, The Sleepers and the Shadows, vol. 1, pp. 87-88. ↩

- Grieve, The Sleepers and the Shadows, vol. 1, p. 174, only documents the existence of this inn from 1620, but the Howard accounts prove beyond question that it was functioning in the second half of the fifteenth century. ↩

- L.J.F. Ashdown-Hill, The client network and connections of Sir John Howard (Lord Howard, first Duke of Norfolk) in north east Essex and south Suffolk, unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Essex, 2008, part 5. ↩

- Speede’s account is cited in J. Throsby, Memoirs of the Town and County of Leicester, Leicester 1777, p. 61, n. b. ↩

- Alex Dawson, Leicester Mercury, Thursday 2 March 1995 ↩

- Ben Farmer, Leicester Mercury, Wednesday 11 May 2005. ↩

- J. Ashdown-Hill, The Fate of Richard III’s Body http://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/myths_legends/england/leicester/article_4.shtml, and The Last Days of Richard III, Stroud 2010, 2013, chapter 12. ↩

- A. J. Carson (ed.), Finding Richard III – the Official Account, Horstead 2014, p. 83 ↩

- C.J. Billson, Mediaeval Leicester, Leicester 1920, p.103, present writer’s emphasis. ↩

- Billson, Mediaeval Leicester, pp. 178-79, citing W. Kelly, Royal Progresses and Visits to Leicester, Leicester 1884, present writer’s emphasis. ↩

- History of the Blue Boar http://www.le.ac.uk/richardiii/history/blueboarinn.html (consulted September 2014). ↩

- A.F. Sutton & L. Visser-Fuchs, ‘The Making of a Minor London Chronicle in the Household of Sir Thomas Frowyk (died 1485)’, Ricardian, vol. 10, no. 126, September 1994, pp. 86-103 (p. 97), present writer’s emphasis. ↩

- H.M. Colvin, J. Summerson, M. Biddle, J. R. Hale & M. Merriman, The History of the King’s Works, vol. 4, 1485-1660, part 2, London (HMSO) 1982, p. 1 ↩

- H.M. Colvin, D.R. Ransom & J. Summerson, The History of the King’s Works, vol. 3, 1485-1660, part 1, London (HMSO) 1975, p. 179, citing Levi Fox, Leicester Castle, Leicester 1944, pp. 30-35. ↩

- Billson, Mediaeval Leicester, p. 200. ↩

- H. Gill, A Short History of Nottingham Castle, 1904, http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/gill1904/charlesi.htm (consulted October 2015). ↩

- Colvin, Ransom & Summerson, The History of the King’s Works, vol. 3, p. 405. ↩

- H. Gill, A Short History of Nottingham Castle, 1904, http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/gill1904/charlesi.htm (consulted October 2015). ↩

- TNA, PSO 1/22; TNA, C 81/791. ↩

- TNA, C 81/798. ↩

- 25 July – TNA, C 81/798. ↩

- TNA, PSO 1/31; TNA, C 81/820. ↩

- 31 March 1470, TNA, C 81/831. ↩

- TNA, PSO 1/34; TNA, C 81/832. ↩

- J. Bruce, ed., Historie of the Arrivall of Edward IV in England, London 1838 p. 8. ↩

- J. Gairdner, ed., The Paston Letters, 1904, Reprinted Gloucester 1983, vol. 5, p. 179. ↩

- Gairdner, ed., The Paston Letters, vol. 5, p.181. ↩

- TNA, C 81/844. ↩

- TNA, C 81/845. ↩

- TNA, C 81/847. ↩

- Thursday 11 July 1476, TNA, PSO 1/42. ↩

- ‘Richard often stayed at Leicester Castle when visiting the city(sic)’. Discover Richard III, pamphlet published by Leicester Shire promotions, Leicester 2003, last page. ↩

- R. Edwards, The Itinerary of King Richard III 1483-1485, London 1983, p. 6, citing Harl. 433, vol. 2, pp. 8-10, and TNA (PRO) C 81/886. ↩

- Edwards, The Itinerary of King Richard III 1483-1485, p. 9, citing CPR pp. 367, 375. ↩

- Edwards, The Itinerary of King Richard III 1483-1485, p. 22, citing TNA (PRO), C 81/898. ↩

- Edwards, The Itinerary of King Richard III 1483-1485, p. 27, citing TNA (PRO), C 81/901. ↩