May, 1940 and things looked bad for Britain. Very bad indeed.

The bulk of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), combined with assorted allied units, was being driven backwards into an ever shrinking pocket of land around the French coastal town of Dunkerque (Dunkirk). The German Army had swept through France smashing through all resistance placed before it with astonishing speed. The fall of France was inevitable and the destruction of the remaining elements of Britain’s Army seemed equally unavoidable.

However, salvation was at hand and it originated from a most unlikely source; a series of tunnels built during the Napoleonic Wars deep below Dover Castle.

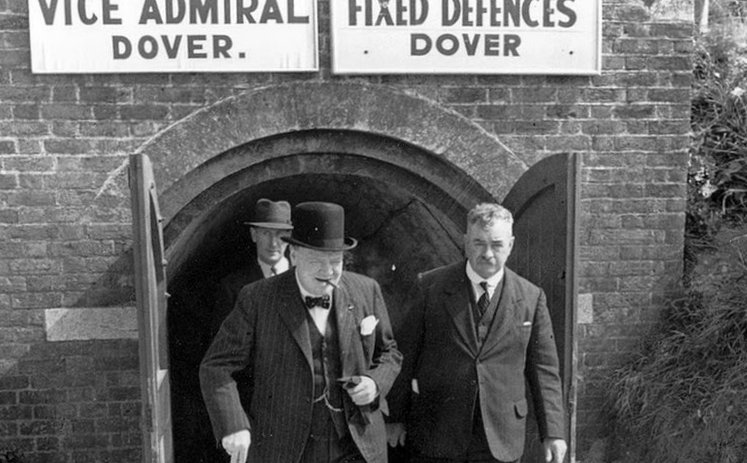

© Imperial War Museum

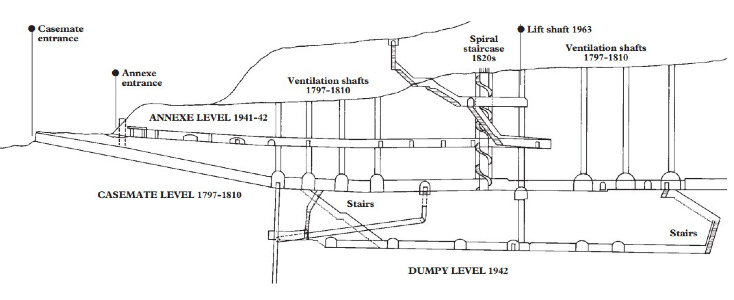

Originally built as barracks to accommodate an additional garrison to deal with the threat of any French invasion, they were capable of housing some 2,000 men around 20 metres below the level of the cliff top. Napoleon never invaded and the tunnels were then taken over by the Coast Blockade Service, a small unit assembled to combat smuggling in the area. After their headquarters was moved closer to the shore the tunnels were effectively closed, being used only for storage and emergency billeting over the course of the next 110 years. During 1938 it became obvious to most of our military leaders that war with Germany was a strong possibility and, in an astute move, the tunnels below Dover Castle were reopened and adapted as a bomb-proof and secure Naval Headquarters. At the outbreak of war these headquarters became responsible for the command of the Channel coast and it was here that Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay and his staff planned and supervised the rescue of allied troops from the beaches of Dunkirk, under the operational codename of Operation Dynamo. Between 27th May and 4th June 1940 over 338,000 British and allied troops were rescued from the beaches of Dunkirk, in an operation masterminded from beneath Dover Castle.

Hermann Goering had promised that his Luftwaffe would destroy the British on the beaches at Dunkirk, but in relying on this promise for too long, and possibly also becoming cautious due to a British-led counter attack on the 21st May, Hitler allowed his army’s advance to slow and even stop for a period of days. This breathing space allowed Ramsay the chance to organise an evacuation on a massive scale with the British Navy, under RAF protection, rescuing the bulk of the trapped army from under the noses of the Germans. The British Navy were also famously assisted in this endeavour by many small, privately owned boats, known as the “little ships”. So, with a lot of planning, acts of enormous courage, some good fortune and some inexplicable errors by the Germans, the “miracle” of Dunkirk had been achieved.

Dunkirk was, of course, a defeat bordering on disaster, with the loss of all heavy weapons and transport, and of 243 assorted vessels and 106 fighter aircraft involved in the evacuation. But this defeat had somehow been made to look like a victory, in much the same way that, during the Zulu War some 61 years before, Rorke’s Drift had allowed the nation to largely ignore the humiliation suffered at Isandlwana only a day earlier. Whilst Dunkirk had been a defeat, Britain still had an army and the rescue of so many fighting men meant that Britain could fight on. Without them the pressure on Churchill to make peace may have proved irresistible.

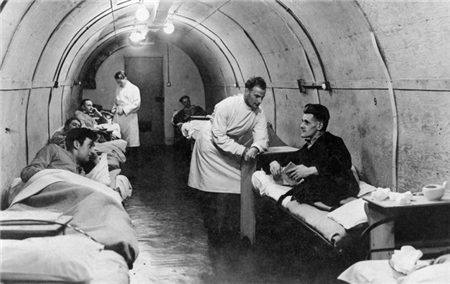

During 1941 the tunnels were further adapted with an Annexe level being excavated and used as a dressing station; containing two operating theatres and basic patient accommodation. A military telephone exchange was also installed during 1941, enabling direct communication with vessels, as well as air-sea rescue craft; thus enabling greater efficiency in rescuing pilots that had been shot down in the Straits of Dover. The switchboards of this exchange were in constant use during this time and a new tunnel had to be created alongside them in order to house the massive batteries and chargers that were required in order for them to function.

By 1942 a decision was made to locate a combined headquarters in the tunnels incorporating all three services – Army, Navy and Air Force – and this larger network of tunnels, codenamed Dumpy level, was dug 15 metres below the original tunnels and completed in 1943. After the war the headquarters was closed and Dover Castle’s role at the heart of England’s defence, via its network of tunnels, was for the time being to remain secret.

Almost as soon as the tunnels were closed the onset of the Cold War led to them being reopened, as they were adopted by the Home Office as one of 12 emergency Regional Seats of Government which would take charge of the country in the event of nuclear attack. Large sums of money were spent adapting Dumpy level at the heart of the operation, equipping it with generators, plant, furniture and numerous stockpiles of stores. This prospective safe haven for 300 government officials and military chiefs remained in place until 1986, when it was finally decided that, along with many other drawbacks in housing this facility in tunnels that were in generally poor condition, the chalk cliffs themselves would be unable to provide any protection from the effects of radiation.

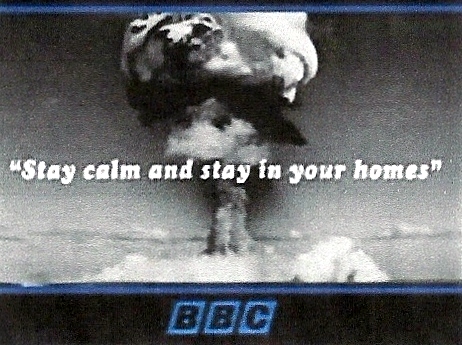

Secret exercises carried out by NATO from Dumpy just days before the start of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 revealed just how unprepared Britain would have been in dealing with the aftermath of a nuclear strike. Indeed for many years during the Cold War there seemed to be an almost naive stance as to just what the effects of a nuclear conflict would be.There are the famous (or should that be infamous?) government information films (part of the Protect and Survive series) of what to do prior to and during a nuclear attack. Narrated by Patrick Allen they contain invaluable survival advice for members of the public, such as building a shelter under the stairs as a “fallout room”, shutting windows and drawing the curtains. If caught out in the open during an attack, then throwing yourself onto the ground and covering your head with your clothes is the recommended course of action. Call me pessimistic, but armed with such information I don’t think things would have worked out too well.

It might seem inconceivable to anybody under the age of 30, but between the years 1949 up until the mid 1980’s there was a real and continuous threat of annihilation, or at best the end of the world as we knew it.The world may have changed regarding a nuclear apocalypse, but the fears essentially remain the same, with the most likely world’s end scenario now envisaged through natural or terrorist unleashed disease.

It might seem inconceivable to anybody under the age of 30, but between the years 1949 up until the mid 1980’s there was a real and continuous threat of annihilation, or at best the end of the world as we knew it.The world may have changed regarding a nuclear apocalypse, but the fears essentially remain the same, with the most likely world’s end scenario now envisaged through natural or terrorist unleashed disease.

Most of Dover Castle’s network of secret tunnels is now open to the public and an interactive display of the events before and during Operation Dynamo accompanies the visitor during their tour of the tunnels. There is a shorter, but still impressive display of a wartime medical emergency in the Annexe level operating theatre. Separate and specific tours are periodically available to view what was effectively the nuclear bunker at Dumpy level.

Dover Castle’s wartime tunnels are worth a visit on their own and whilst being a fitting tribute to the skill and bravery of those that worked and lived underground during WW2, they also provide a chilling reminder of what could have been if the Cold War had escalated into WW3.

Dover Castle on Twitter @EHdovercastle

Dover Castle Facebook page

Neil Kemp is a keen and passionate amateur historian and prize winning photographer who lives in Margate, on the North Kent coast in the United Kingdom. Before retiring he worked both with and at Margate Museum, overseeing budgets on a number of historical projects.