There is something quite magnificent about seeing Shakespeare done properly. Especially the comedies. Raucous, ribald, rude and rambunctious, done properly a Shakespeare comedy is quite improper. No one does it better than the thespians of The Globe Theatre. Of course a trip to Shakespeare’s own theatre (well, a modern reconstruction as close as practically possible to the original) in Southwark, England, to take in a performance on a Saturday night, is for most of us, probably a once in a lifetime opportunity. Fortunately the good fellows of The Globe have committed three of their most brilliant and uproarious performances to film. Henry V, Twelfth Night and The Taming Of The Shrew, which we caught recently at the Palace Theatre, Brighton.

There is something quite magnificent about seeing Shakespeare done properly. Especially the comedies. Raucous, ribald, rude and rambunctious, done properly a Shakespeare comedy is quite improper. No one does it better than the thespians of The Globe Theatre. Of course a trip to Shakespeare’s own theatre (well, a modern reconstruction as close as practically possible to the original) in Southwark, England, to take in a performance on a Saturday night, is for most of us, probably a once in a lifetime opportunity. Fortunately the good fellows of The Globe have committed three of their most brilliant and uproarious performances to film. Henry V, Twelfth Night and The Taming Of The Shrew, which we caught recently at the Palace Theatre, Brighton.

From costume to staging, the entire production is gloriously medieval. The simplicity lends an authenticity to the experience that is breathtaking. The performances are more than just captivating, they are enthralling. You will find yourself with the actors on the stage, and in amongst the audience, and you will feel a shared experience with audiences from some 500 years ago. Not just a cinema or a theatre performance. Almost a time machine. Also, afterwards, your face will ache from laughter, and you will feel an irresistible urge to stride about DECLARING EVERYTHING IN A MANNER MOST ARCHAIC, AND LOUD, like a theatre actor of the oldest school. You may frighten the cat, the neighbours, and receive bemused or mortified looks from partners or children. It will be worth it.

For many of us our experience of Shakespeare in the theatre is probably limited to stilted high school performances, or ‘artistic’ college interpretations. Unfortunately Joss Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing has a little of the latter. Transposing Renaissance Sicily to sophisticated modern California just doesn’t quite ring true.

For many of us our experience of Shakespeare in the theatre is probably limited to stilted high school performances, or ‘artistic’ college interpretations. Unfortunately Joss Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing has a little of the latter. Transposing Renaissance Sicily to sophisticated modern California just doesn’t quite ring true.

Presented in a cool monochromatic B&W again seems an odd choice. It has been reported that B&W was somehow a reference to the screwball comedies of the 1930s. With its intimate, fly-on-the-wall and occasionally voyeuristic point of view, its heritage feels more like the classic jazzed up versions of Shakespeare from the 1960s, such as Basil Dearden’s brilliant take on Othello from 1962, All Night Long. The passion of Shakespeare demands colour, or at least contrast.

Whedon famously invited his cast during breaks in production on the TV shows Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Angel to his home to read Shakespeare. Perhaps part socializing and part acting workshop. And it seemed to pay off, his cast of young actors brought a passion, a drama and wit worthy of the Bard to the now classic TV shows. Whedon’s Much Ado had its genesis in those sessions. The film was shot at his home in Santa Monica, over two weeks in October, 2011, while on a break from post production on Marvel’s The Avengers. The brief filming schedule seems to have resulted in some knee-jerk criticism, with claims that it feels like a ‘pet project’. There are many great films shot on a tight schedule, Stephen Spielberg’s Duel, the epic Russian Ark, the low budget horror successes The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity. Roger Corman’s cult classic from 1960, The Little Shop Of Horrors was infamously shot in two days and one night. Shooting to schedule is based on planning and logistics, and with Whedon’s extensive TV experience, he is doubtless a master of the art. As a basis for criticism it is invalid.

Do the social mores and sexual politics of Renaissance Italy or Elizabethan England translate to 21st century California? No. Marriage amongst noble families was more often than not an alliance; intimately tied to social status, political power and business advancement. While the play encompasses wry, witty and even soulful contemplations on gender roles, the ‘battle of the sexes’ that perhaps in many ways is still relevant today, in other ways it is not. The transposition to the same era, the same social milieu, the same landscape as Calfornication, renders the necessary controversies irrelevant. Watching Joss Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing, one finds oneself wishing for palatial Italian scenery, imagining Renaissance costumes, and transforming American twangs to English accents. Conversely, perhaps a complete rewrite of the text, from the language of Shakespeare to that of modern California, while maintaining the story, may have resulted in an insightful classic rather than an entertaining curiosity.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F6QV0UAifXQ

The influence of Shakespeare on fantasy and sci-fi, especially in television, cannot be underestimated. From Doctor Who to Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Shakespeare provides a ready source of witty rejoinders, enthralling plots, profound quotes, and archetypal characters to lend a little cleverness or gravitas to any episode.

The influence of Shakespeare on fantasy and sci-fi, especially in television, cannot be underestimated. From Doctor Who to Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Shakespeare provides a ready source of witty rejoinders, enthralling plots, profound quotes, and archetypal characters to lend a little cleverness or gravitas to any episode.

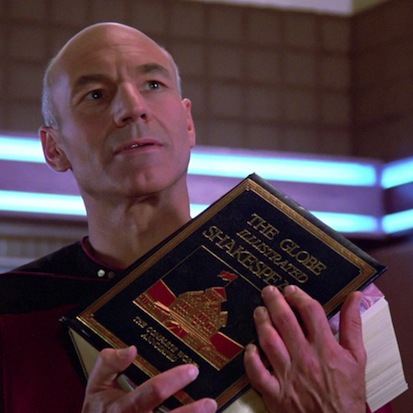

The influence on Star Trek goes beyond a few select phrases. Characters quote Shakespeare, episodes are given significance by being titled after variations of well known Shakespearean phrases, entire episodes have plots directly transposed from Shakespeare. Episode 13 of the original series, The Conscience Of The King, features a murder mystery akin to Hamlet, with the leader of a Shakespearean acting troupe the chief suspect in a massacre. What captures the imagination is the notion that in the distant future, space-borne Shakespearean acting troupes will still wander from planetary settlement to settlement, presenting the Bard’s work, as strolling players have done since Elizabethan times. Even the Klingons claim Shakespeare as their own, (clearly, the very name expresses the Klingon warrior spirit) and long before Jean-Luc Picard’s commanding voice was heard on the bridge of the Enterprise, Patrick Stewart was a Shakespearean actor. He joined the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1966, the same year the original Star Trek series was first broadcast.

Captain Kirk has boldly taken Shakespeare, to quote the popular phrase, “where no man has gone before.” William Shatner’s The Transformed Man, his debut album released in 1968, combining spoken word, poetry, and Shakespearean soliloquies counterpointed with contemporary music, is a work of genius on so many levels, whether it is good Shakespeare is a moot point. It’s epically kitschy, outrageously dramatic, purely surreal, filled with a hope and an artistry perhaps reflective of its times.

Captain Kirk has boldly taken Shakespeare, to quote the popular phrase, “where no man has gone before.” William Shatner’s The Transformed Man, his debut album released in 1968, combining spoken word, poetry, and Shakespearean soliloquies counterpointed with contemporary music, is a work of genius on so many levels, whether it is good Shakespeare is a moot point. It’s epically kitschy, outrageously dramatic, purely surreal, filled with a hope and an artistry perhaps reflective of its times.

His later renditions of popular songs, from Elton John’s Rocket Man, Blur’s Common People, David Bowie’s Space Oddity and Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, in the inimitable Shatner style, somehow kitsch and ironic and yet powerful and genius at the same time, just further cements his status as a living legend. The Transformed Man is Shakespeare at its most improper. And yet there is something about it that is utterly compelling. Watch it, I dare you. You will think it’s terrible. You will smile. You will wonder. You will be confounded. You may experience shivers, you will experience joy. You will never be the same.