Would Scorcese have received an Oscar sooner if he’d directed Clockers? Would The Golden Compass have gone on to be the epic three movie event it should have been if they had stuck with Tom Stoppard’s script? We take a closer look at these and other great films that could have been.

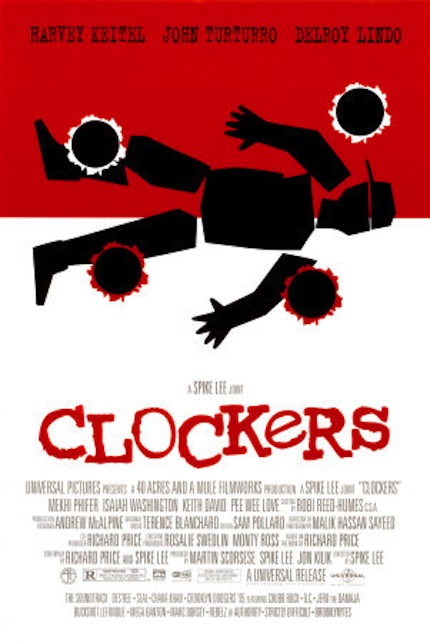

Clockers, 1995, Directed by Spike Lee

Martin Scorcese was slated to direct, Clockers, and the story has all the hallmarks of a Scorcese classic. An unexplored piece of New York history, a society stratified by ritual and code, endemic violence, guilt, corruption and redemption. Scorcese would have brought some of his signature force to a story of an individual, displaced within his culture, in a story that seems almost tailor made for him.

Martin Scorcese was slated to direct, Clockers, and the story has all the hallmarks of a Scorcese classic. An unexplored piece of New York history, a society stratified by ritual and code, endemic violence, guilt, corruption and redemption. Scorcese would have brought some of his signature force to a story of an individual, displaced within his culture, in a story that seems almost tailor made for him.

It’s deleterious when the choice of the director becomes part of the marketing. Even more so when the race of the director becomes a part of the marketing. Shows you what can happen can happen when producers and marketeers have too much say in the work of auteurs. Don’t get me wrong, I love Spike Lee. In fact he could be a Scorcese character. For me there’s little higher praise. Spike Lee was great when he was doing his cool jazzy hip hop Brooklyn clash of cultures thing, Do The Right Thing, She’s Gotta Have It, Mo’ Better Blues, but in Clockers he couldn’t leave a certain kind of middle class intellectualism behind. Clockers wasn’t about a clash of cultures. It was about a culture imploding because of drugs and violence, and a few people, caught in the middle. Based on Richard Price’s novel that explored the drug and crack culture that blighted black neighborhoods like a consuming alien force from the 70s and into the 90s. Price, famed for books like The Wanderers, and screenplays like The Color Of Money, (directed by Scorcese) went into the hoods to write the novel. Not surprising, he grew up in housing projects in the North East Bronx. Price went on to work on The Wire, and this brought the grim and gritty urban monster right into our living rooms, into our faces, which is what the novel did, and what the movie should have done. Spike Lee’s felt a little too suburban. Lee was born in Atlanta, Georgia his mother was a teacher of arts and black literature, his father a jazz musician and composer. He moved to Brooklyn when he was young. Perhaps not far physically from The Bronx, but with its tree line streets and pleasant Brownstone buildings, a million miles culturally from high rise tenements and derelict wreckage filled lots – the milieu of Clockers. I’m not saying that a filmmaker’s cultural and experiential heritage should inform everything they do, but to some extent it is inevitable. The most significant thing Spike Lee seemed to do was change Vanilla Yoo-hoo to Chocolate Moo. The flavour of the beverage is not a political statement. However, Strike’s consumption of Vanilla Yoo-hoo, his stuttering are elements Lee changed that were not only crucial to the character, but crucial to the plot. Scorcese would have brought the air of menace, of chaos barely held in check, of impending violence, he would have returned the film to its origins, the mean streets.

The Golden Compass, 2007, Directed by Chris Weitz

Sir Tom Stoppard is the author of ground breaking, award winning plays like Rosencrantz And Guildenstern Are Dead, Travesties, Arcadia, The Coast Of Utopia, and award winning screenplays and adaptations including A Separate Peace, Brazil, Empire Of The Sun, Shakespeare In Love, Anna Karenina, author of numerous plays for the small screen and radio, he’s also uncredited on the screenplays for Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade, Star Wars III: Revenge Of The Sith and Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow. Which is to say he brought not inconsiderable experience to the project when he penned the initial adaptation of the script for Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass. Stoppard’s script was rejected as being too weighty, as dealing with issues such as the corrupt Majesterium, a sort of ruling religious government and inquisition in Pullman’s books. Of course Stoppard has often addressed issues of human rights, censorship, the fight against oppression, political freedom, as well as being renowned for wit, intelligence, philosophy and humour in his work.

Sir Tom Stoppard is the author of ground breaking, award winning plays like Rosencrantz And Guildenstern Are Dead, Travesties, Arcadia, The Coast Of Utopia, and award winning screenplays and adaptations including A Separate Peace, Brazil, Empire Of The Sun, Shakespeare In Love, Anna Karenina, author of numerous plays for the small screen and radio, he’s also uncredited on the screenplays for Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade, Star Wars III: Revenge Of The Sith and Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow. Which is to say he brought not inconsiderable experience to the project when he penned the initial adaptation of the script for Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass. Stoppard’s script was rejected as being too weighty, as dealing with issues such as the corrupt Majesterium, a sort of ruling religious government and inquisition in Pullman’s books. Of course Stoppard has often addressed issues of human rights, censorship, the fight against oppression, political freedom, as well as being renowned for wit, intelligence, philosophy and humour in his work.

Stoppard seemed a perfect fit. However, dealing with the religious and philosophical issues that were central to the books, themes inextricably entwined with the adventure story of Lyra and Will, had the producers running scared. They wanted to back away from the controversial religious aspects of the story. Unfortunately that was the heart of the story as well. The producers went with the script by the brother of the director, probably best known for his work on American Pie. This is a heartwarming American family comedy whose whose high points include having sex with a pie, someone eating that pie, and a discussion of inserting a flute in one’s orifices at band camp. These rather American concerns seem somewhat at odds with issues of free will, spirituality, the nature of man, the nature of existence that were the themes of the books, and of Stoppard’s equally weighty script.

It really does beggar belief how anyone thought a script from the author of a peurile teen comedy could somehow do justice to a work that addressed some of the most important issues of the last 500 years.

Nevertheless, the film that resulted wasn’t bad. The performances from the actors, and the way Pullman’s alternate world was realised was brilliant. But it was disappointing. It lacked the depth, the heart of the matter that could have made it great. What resulted was an adventure for 7 to 12 year olds. The books were a deep and moving adventure exploring faith, love and creation. The film, Tom Stoppard’s film, could have been too. If this film were a person in Pullman’s universe, you’d probably figure they had been captured by Gobblers and had their Daemon split away by intercision. It lost the essential spark, creativity, curiosity. The questioning of authority that is one of the book’s central themes. The result was merely a tale of a little girl who runs away with gypsies to save her friend. Perhaps like the BBCs TV adaptation of True Tilda by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch. Tom Stoppard’s The Golden Compass could have been so much more.

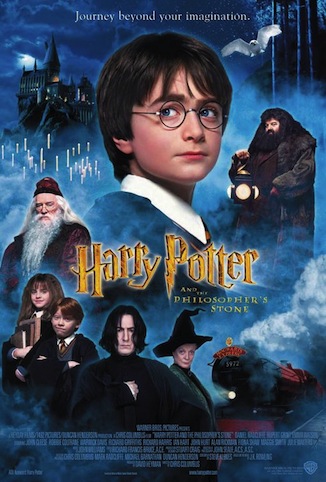

Harry Potter And The Philosopher’s Stone, 2001, Directed by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus brought a little Disney with him to the production of the first Harry Potter film. Exactly what it didn’t need. Hogwart’s looked like a castle themed restaurant, not an ancient school steeped in tradition and magic. Richard Harris, who we loved in everything else he ever did, brought weariness to the role of Dumbledore. Yes, the rest of the casting was brilliant, but that was entirely done by producer David Hayman. But the kind of slapstick hijinks Columbus managed quite well in Home Alone just didn’t cut it for this quintessentially English children’s school tale. While an English director is not absolutely required, what is required is someone with a feel for the peculiar eccentricity of the English. Who better than Terry Gilliam, who spent his formative years with the most eccentric of all English performing troops, Monty Python. Co-directing with Terry Jones Monty Python And The Holy Grail, then the Pythonish productions Jabberwocky, before moving on to his own particular style of surreal modern fantasies, Time Bandits, Brazil, 12 Monkeys, The Brothers Grimm and The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus amongst others.

Christopher Columbus brought a little Disney with him to the production of the first Harry Potter film. Exactly what it didn’t need. Hogwart’s looked like a castle themed restaurant, not an ancient school steeped in tradition and magic. Richard Harris, who we loved in everything else he ever did, brought weariness to the role of Dumbledore. Yes, the rest of the casting was brilliant, but that was entirely done by producer David Hayman. But the kind of slapstick hijinks Columbus managed quite well in Home Alone just didn’t cut it for this quintessentially English children’s school tale. While an English director is not absolutely required, what is required is someone with a feel for the peculiar eccentricity of the English. Who better than Terry Gilliam, who spent his formative years with the most eccentric of all English performing troops, Monty Python. Co-directing with Terry Jones Monty Python And The Holy Grail, then the Pythonish productions Jabberwocky, before moving on to his own particular style of surreal modern fantasies, Time Bandits, Brazil, 12 Monkeys, The Brothers Grimm and The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus amongst others.

Gilliam expressed his philosophy in an interview with novelist Salman Rushdie, “Well, I really want to encourage a kind of fantasy, a kind of magic. I love the term magic realism, whoever invented it – I do actually like it because it says certain things. It’s about expanding how you see the world. I think we live in an age where we’re just hammered, hammered to think this is what the world is. Television’s saying, everything’s saying ‘That’s the world.’ And it’s not the world. The world is a million possible things.”

Gilliam’s often explored themes of the struggle between spirituality, the creative, the imaginative and cold, modern rationality, and characters thrown from the mundane to the extraordinary, and finding themselves battling a cold, authoritarian power are an excellent match for the Harry Potter universe. J K Rowling has long been a fan of Gilliam’s work and he was her first choice to direct Harry Potter. Warner Bros. decided to go with Chris Columbus. Columbus is known for popular but essentially gimmicky films such as Gremlins, Goonies, Mrs Doubtfire and Home Alone. Lacking the sort of explorations of life, death, love and meaning essential to the books. Gilliam, and the rest of the world, was amazed at the decision, “I was the perfect guy to do Harry Potter. I remember leaving the meeting, getting in my car, and driving for about two hours along Mulholland Drive, just so angry. I mean, Chris Columbus’ versions are terrible. Just dull. Pedestrian.”

David Yates, director of the last three (and best) of the Harry Potter films, paid homage to Gilliam; his designs for the Ministry Of Magic controlled by the fascist-like Death-Eater faction were reminiscent of Gilliam’s totalitarian bureaucracy in Brazil. Gilliam has said, in retrospect he probably wouldn’t have liked working on any project where the size of the budget tends to bring interference from studio executives. We’re sure, with Jo Rowling’s support, and perhaps an Expelliarmus or two, the Warner execs intermeddlesomeness could easily have been discouraged.

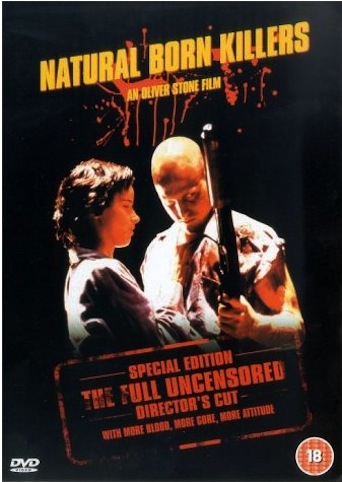

Natural Born Killers, 1994, Directed by Oliver Stone

Natural Born Killers could have very easily been Quentin Tarantino’s first film, the ultimate pop serial killer tabloid freakshow. He wrote the original screenplay, which was heavily modified, resulting in Oliver Stone’s somewhat strained version. The talent, Juliette Lewis, Woody Harrelson, Robert Downey Jnr, was spectacular. Stone is no slouch himself when it comes making a a good movie; Salvador, Platoon, JFK, Wall Street, Born On The Fourth Of July and more are all intense examinations of American life. So there was no obvious reason why the film wouldn’t be brilliant.

Natural Born Killers could have very easily been Quentin Tarantino’s first film, the ultimate pop serial killer tabloid freakshow. He wrote the original screenplay, which was heavily modified, resulting in Oliver Stone’s somewhat strained version. The talent, Juliette Lewis, Woody Harrelson, Robert Downey Jnr, was spectacular. Stone is no slouch himself when it comes making a a good movie; Salvador, Platoon, JFK, Wall Street, Born On The Fourth Of July and more are all intense examinations of American life. So there was no obvious reason why the film wouldn’t be brilliant.

When Stone first approached the script, he saw it as straight crime action, perhaps something like Bonnie and Clyde meets Kalifornia, but as the project developed, the sideshow of the media on stories like the O J Simpson case, the Menendez brothers case, the Rodney King beating and the FBI/ATF assault on the Branch Davidian sect in Waco, Texas, and the role of the media in glorifying and marketing violence for the sake of ratings, he changed the direction from action to a satirical critique of the media’s obsession. Curiously enough Tarantino’s script focused more on Robert Downey Jnr’s character, trashy journalist Wayne Gale. Stone’s crime action take on it had refocused on the killers, Mickey and Mallory, but in coming full circle, again focusing on the tabloid media aspect, even in the almost psychedelic hacked-up channel-surfing on amphetamines style of the film, (it had near 3000 cuts, most films have 600-700) it still seemed to flatten. Perhaps it had become too televisual rather than cinematic. As a satire on how violence is exploited and serial killers are adored by the US media, perhaps it became the very thing it was satirising.

Tarrantino said “It’s not going to be my movie, it’s going to be Oliver Stone’s, and God bless him. I hope he does a good job with it. If I wasn’t emotionally attached to it, I’m sure I would find it very interesting. If you like my stuff, you might not like this movie. But if you like his stuff, you’re probably going to love it.” Stone took a psychedelic blow torch the American media’s love affair with violence, while Tarrantino tends to revel in that violence, to give it a certain comic book cool to his charcters, they are never the caricatures that they became in Stone’s version.

Stone initially follows Tarrantino’s script, introducing Mickey and Mallory, a couple in the depths of their folie a deux, murdering and mayhemming their way across the USA, gaining cult celebrity status. Tarrantino’s script centres on the central plot, as hypocritical and cynical reporter Wayne Gale schemes to interview the killer couple for his exploitative tabloid TV show American Maniacs. Scenes then cut back and forth between the crucial events that established Mickey and Mallory’s progress and fame, from their crime spree to capture, to an amzing courtroom scene which almost turns the tables. Finally culminating in the interview for American Maniacs, where the killers critiquing the culture that has made them, escape in the midst of prison riot and bloody chaos, with Gayle as their prisoner.

It’s essentially the same story, but without Tarantino’s twisted take on the traditional biopic structure, the climactic life event to which everything was building, resluting not in interview and execution but rather escape, renewal and retribution. Stone’s version lost focus, lost impact, lost dramatic tension.

Stone’s film is always worth another view, but essentially it becomes a scattered bunch of scenes lost in the flickering ADD channel-surfing morass of the modern media. It merges with the media it critiques, rather than standing out as the powerful narrative it could have been.

John August, writer of Go, Titan AE, Charlie’s Angels, Big Fish, The Corpse Bride, Dark Shadows, Frankenweenie and others, co-writer of the novelisation of Natural Born Killers has said when he first read Tarantino’s original screenplay, he had to immediately flick back to the start and read it again; it was best script he’s ever read. It could have been Tarantino’s most incisive, most serious, his first and greatest film.

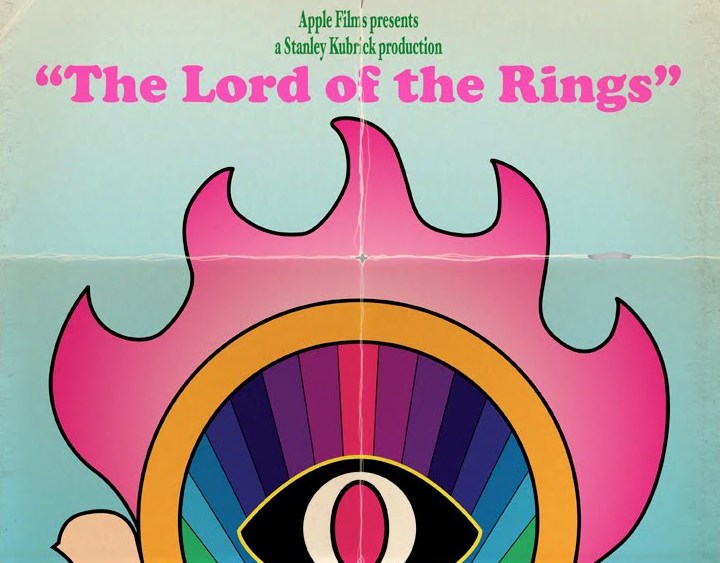

The Lord Of The Rings, 1978, Directed by Ralph Bakshi

Before you curse me for an oaf with the sensibilities of an orc, let me repeat that; Ralph Bakshi’s Lord Of The Rings – the animated film from 1978. No I am not insulting Peter Jackson’s masterpiece or in anyway saying it had many poor choices. That’s another battle.

Bakshi was known for cult animation films including Fritz The Cat, Heavy Traffic and Wizards in the 1970s, and had worked on more conventional animation for TV before that, shows such as Heckle & Jeckle, Deputy Dawg, Spider-Man and Mighty Mouse. In conjunction with producer Saul Zaentz, he brought all that experience, both good and bad, to the Lord Of The Rings. Some of the artwork for his LOTR has great charm, great appeal, some of it is frankly bizarre. As a film it is fundamentally flawed. Yes, for many years it has had a cult following of dedicated Tolkien fans, shown at conventions, watched on video at epic D&D gatherings. But that’s because, at the time their was nothing else available. The odd mix of traditional cel animation with hybrid overpainted rotoscoped footage just never worked. In his previous film Wizards, a battle between the forces of fantasy and Nazis, set in a distant future, Bakshi used the same rotoscoping techniques to save money. Painting over stock footage of advancing German forces, he produced the same kind of heavy black and red enemy we see in his LOTR. As the Orcs march on Helm’s Deep you quite expect to see tanks and Nazis with them. Many characters were left out, And due to running out of money and a dispute with United Artists, the film was incomplete, ending after Helm’s Deep.

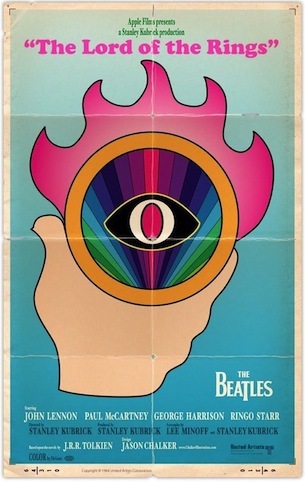

The final release was disjointed, inarticulate. While some of the cel animation had a certain charm, and some of the rotoscoped live action was quite intense and surreal, together it was like a Rankin-Bass special on bad brown acid. How much better would it have been on something more pure, and it could have been, because, in 1969 The Beatles and Stanley Kubrick considered making an animated version of The Lord Of The Rings.

It wouldn’t have been LOTR as we know it, but it would have been magnificent. Kubrick had directed legendary cult classics Dr Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey, amongst others, The Beatles’ The Yellow Submarine, directed by George Dunning and with art design by Heinz Edelman, produced by United Artists and King Features in 1968 was a runaway hit, ‘delighting both adolescents and esthetes alike’ according to Time magazine. When the Beatles learned that Tolkien had sold the rights to United Artists in 1969, they proposed the project to Stanley Kubrick. Kubrick turned it down, telling John Lennon he thought the novel could not be adapted into a film due to its immensity. Tolkien also objected to the involvement of The Beatles. While John Lennon had long been a fan of Tolkien’s work, the reverse was not the case. In a 1964 letter to Christopher Bretherton ,Tolkien complained of the noise in his formerly quiet Oxford street, “in a house three doors away dwells a member of a group of young men who are evidently aiming to turn themselves into a Beatle Group. On days when it falls to his turn to have a practice session the noise is indescribable.” Did this unknown musician prejudice Tolkien and prevent the creation of a masterpiece, the one psychedelic film to rule them all?

Check out more of Jason Chalker’s artwork here.