Elizabeth Norton has brought us intriguing and compelling historical studies and biographies, looking at both the famous and infamous Queens of England, the consorts of King Henry VIII, his mistress and the mother of his first son Elizabeth Blount, and other equally remarkable but lesser known figures; the elusive Anglo-Saxon queen Elfrida, the great Tudor matriarch Margaret Beaufort. In her latest book, she continues to bring us a unique perspective of the historical female experience. The Lives of Tudor Women gives a fascinating behind-the-scenes look into the lives of women through the “Seven Ages” of life, from childhood, to youth, to old age, from the lives of the great and good, to the family and working life of ordinary women.

Elizabeth Norton has brought us intriguing and compelling historical studies and biographies, looking at both the famous and infamous Queens of England, the consorts of King Henry VIII, his mistress and the mother of his first son Elizabeth Blount, and other equally remarkable but lesser known figures; the elusive Anglo-Saxon queen Elfrida, the great Tudor matriarch Margaret Beaufort. In her latest book, she continues to bring us a unique perspective of the historical female experience. The Lives of Tudor Women gives a fascinating behind-the-scenes look into the lives of women through the “Seven Ages” of life, from childhood, to youth, to old age, from the lives of the great and good, to the family and working life of ordinary women.

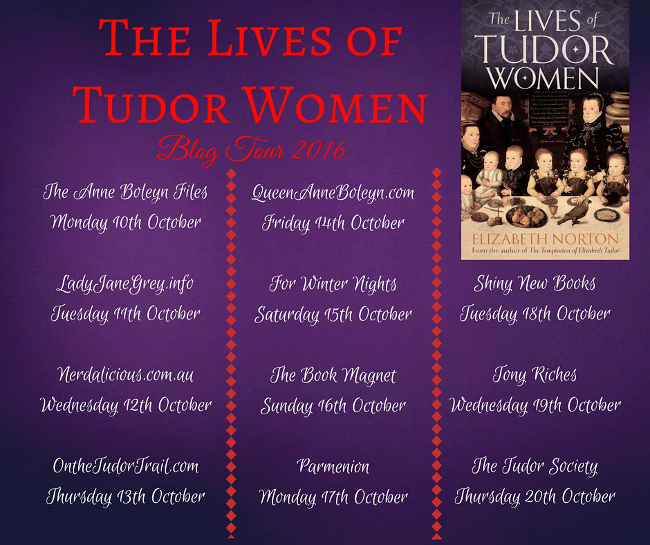

Elizabeth joins us on the third day of her The Lives of Tudor Women book tour to discuss the Seven Ages of Tudor Women.

The Seven Ages of Women by Elizabeth Norton

To the people of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century England, life could be divided into phases – the Seven Ages of Man, articulated most famously by Shakespeare, in As You Like It, as an infant, schoolboy, lover, soldier, the justice of the peace, the ageing retiree and, finally, the infirm elder. From the female perspective, those Ages could never apply in quite the same way, in an era when women were largely denied any official, public role; but even where the Ages differ, there are yet analogies. With fifty per cent of the Tudor population female and the dynasty reaching its glorious climax in the life of its greatest queen, the Seven Ages of Women are pertinent. Never before had an era in English history produced so many eminent and politically active women.

For most Tudors, the first of life’s seven ages, infancy, lasted up to around the age of seven, its early years characterised by Shakespeare as the time of ‘mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms’. The experience of both boys and girls in those first early years was superficially similar, but there were differences too. For boys, it began earlier – 46 days after conception – when the male soul was believed to enter the body and life began. It was later for girls – 90 days – a difference that began a lifetime of differential treatment.

Most Tudor parents wanted a boy and, as pregnancy progressed, they would search for signs that their wish had been gratified. It was theoretically possible, asserted some physicians, to tell the sex, since boys occupied a right chamber to a sub-divided womb and girls the left. This segregation was, of course, a myth (‘but dreams and fond fantasies’), as others rightly realised. Nonetheless, even more enlightened physicians were prepared to assert that carrying a girl was harder work. The mother would therefore have ‘a pale, heavy, and swarth countenance, a melancholic eye’. For the first years after birth, however, there was little to distinguish a boy from a girl. They wore the same clothes, shared the same nurseries and many of the same toys. Tudor parents – like modern ones – found infants adorable, with contemporaries speaking of their ‘sweet baby-talk’ and the delightful first word ‘mamma’. The first age was one of play for all levels of society.

At seven, a Tudor girl was generally regarded as entering her second age, that of adolescence. For Shakespeare, this was the time of the ‘whining schoolboy with his satchel’, ‘creeping like snail unwillingly to school’. It is an engaging image, but it held less true for girls. In the early Tudor period girls were, for the most part, taught informally at home. By the 1530s, it was becoming fashionable for the gentry and nobility to educate their daughters, with the well-heeled leaders of court and county seeking to emulate the example of Thomas More in the education of his three highly accomplished daughters.

Upper class girls could expect a private tutor or, perhaps, being sent to board in a nunnery or the home of a female tutor. Girls were barred from the universities, but a tiny handful were permitted to attend grammar schools. More widely, girls attended the small mixed schools held in many parish churches, where they would learn reading, writing and accounting. A census of the poor taken in Norwich in 1570 shows that even the most impoverished girls were permitted to attend school for a time, although most were pulled out of education to undertake work by the time they were ten.

For most girls, formal education had ended by at least their mid-teens. At that stage, almost everyone boy and girl left home for some form of service. Upper class girls went to serve in the households of their social betters, while those lower down the social scale usually entered into contracts of domestic service.

For Tudors, the third age began around fourteen and was, in Shakespeare’s words, the time of ‘the lover, sighing like furnace, with woeful ballad’. This phase of later adolescence and early adulthood, when the possibilities of love stretched out promisingly, could last for fourteen years, taking a man or woman up to the age of around twenty-eight. It was also thought to be a dangerous time, when young people were most prone to sin. They needed the guiding hand of someone in authority as they negotiated the end of their childhoods.

This was particularly the case for girls, cautioned writers such as the educationalist Juan Luis Vives. Young women should appear in public as rarely as possible, he considered, since their good name and reputation ‘seem to hang by a cobweb’. The danger was that ‘if some slur has attached to a girl’s reputation from men’s opinion of her, it usually remains forever and is not erased except by clear proofs of her chastity and wisdom’. On the successful maintenance of a girls’ reputation hung all her marriage prospects.

Upper class marriage was largely approached as a business arrangements, with the young couple’s fathers haggling over dowries and jointures. Nonetheless, it was expected at all social levels that there should be some liking between the couple, with matches procured when one party was ‘beaten and compulsed’ seen as ungodly. Only a promise to wed and consummation were required to make a valid marriage, although it was prudent for the young couple to secure some witnesses to their vows. Elizabeth I’s cousin, Catherine Grey, learned this to her cost when the fact of her marriage was disputed following the death of one witness and the disappearance of the other.

In an age where knowledge of contraception was rudimentary, motherhood usually swiftly followed marriage. Married women occupied themselves in running their households, raising their children and assisting in their husbands’ businesses. A knowledge of cookery was considered essential by contemporaries, while women were also supposed to have some skills as medicine-makers.

In the Tudor conception, the fourth age of life, beginning around the age of twenty-eight, was traditionally a time of action. For Shakespeare, it was represented by the very masculine image of ‘a soldier, full of strange oaths, and bearded like a pard’. Women, of course, were almost never soldiers. Yet, this phase of adulthood – when they were settled as wives and mothers, or staring in the face of spinsterhood, or experiencing the great independence of widowhood – could become a time of great dynamism and self-realisation. Widows very frequently took over their husbands businesses, such as Katherine Fenkyll, a London draper who took her own apprentices and ran a successful operation. By her old age, she was regularly placed at the top table at the exclusive Drapers’ Company’s annual feasts, in spite of the fact that – as a woman – she could not be a member.

For William Shakespeare, the fifth age of Man was that of ‘the justice’, an official heading towards comfortable retirement. For men, it was the time to reap the rewards of a life well spent: the age of contentment and middle-aged spread. It was in this phase of life that male office-holders were at the height of their power and prestige, patronising the youths that they once had been.

There is little equivalent for Tudor women. No woman entered the Tudor ‘establishment’ to serve as justices of the peace, judges or Church officials. But the nature of the establishment was becoming less stable, and the consequences affected women too. The Reformation, which swept away centuries of tradition in England, also destabilised the lives of many women. From the 1530s, doctrine and the Church became the sites of controversy – and ones in which women, too, sometimes felt they had to take sides.

Margaret Cheyne, Lady Bulmer, who was burned for her part in the Pilgrimage of Grace was one such woman. So too were Anne Askew, who was burned as a heretic by Henry VIII and her friend, Joan Bocher, who was one of only two Protestants burned for heresy during the reign of the equally Protestant Edward VI. During that same reign, Edward’s Catholic half-sister, Princess Mary, came close to fleeing England thanks to her own experience of religious persecution. Yet, she presided over the next regime that burned Elizabeth Cooper and Cecily Ormes at Norwich for their Protestant faith. Under the Protestant Elizabeth I the Catholic Margaret Clitherow was pressed to death at York, while countless others of her female co-religionists endured fines and other penalties for recusancy. The quick-fire changes of religion in the mid-Tudor period caused dramatic changes in the lives of women.

The sixth age of life was the start of old age, believed contemporaries. For some it could be active, even liberating. More commonly, it was regarded, as by Shakespeare, as the time when a man was shifting ‘into the lean and slippered pantaloons,/ With spectacles on nose and pouch on side’. Clothes once filled by muscle had become too large; the once ‘big manly voice’ had turned ‘again toward childish treble’. This sixth age – that of the young-old – was often portrayed as a sad one, of decline and loss, but carrying a sense of the ridiculous, too, as ‘pantaloon’ suggests. It could be this way, too, for women. Perhaps it was so, also for the ageing Elizabeth I, who increasingly came to symbolise her age, and sought to appear ageless as she increasingly covered her face with toxic white lead and her sparse grey hair with wigs. It was claimed that if she happened – by accident – to glance into a looking-glass, ‘she would be strangely transported and offended, because it did not still show her what she had been’.

Worse was, however, to come and the seventh age must have seemed a poor reward to those who managed to survive Tudor infancy, childbirth, disease and accidents. To Shakespeare, the final age was the ‘last scene of all, that ends this strange eventful history’, characterised by ‘second childishness and mere oblivion/ Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything’. In medieval literature, too, the image of a ‘second childhood’ was a common one – if not descending into outright senility, then, like children, contemporaries asserted, the very elderly were foolish and lacking judgement.

The seventh age was a particularly vulnerable time for women, who were always viewed with suspicion. The writer of the wildly popular Women’s Secrets felt able to assert that post-menopausal women were venomous, thanks to a build-up of toxins in their bodies. It was no great leap from that to accuse an elderly neighbour of witchcraft – a concern to many of the aged female poor in Tudor England. There was also no prospect of retirement and the Tudor old worked until physically incapable of doing so. Only a place in a charitable institution could ensure that the poor could enjoy their final years in some comfort.

There was also no prospect of retirement for Elizabeth I, who was approaching seventy in the early years of the seventeenth century. To her subjects, she had become ‘that good old princess the now queen, the eldest prince in years and reign throughout Europe or our known world’, but it was also clear that time was running out. The Tudor dynasty reached its seventh age in the person of the elderly Elizabeth I. It ended on 24 March 1603 in a darkened chamber at Richmond Palace with the old queen’s last gasping breath.

The Lives of Tudor Women by Elizabeth Norton, Published by Head of Zeus 2016

The Lives of Tudor Women by Elizabeth Norton, Published by Head of Zeus 2016

The turbulent Tudor age never fails to capture the imagination. But what was it actually like to be a woman during this period? This was a time when death in infancy or during childbirth was rife; when marriage was usually a legal contract, not a matter for love, and the education of women was minimal at best. Yet the Tudor century was also dominated by powerful and characterful women in a way that no era had been before. Elizabeth Norton explores the seven ages of the Tudor woman, from childhood to old age, through the diverging examples of women such as Elizabeth Tudor, Henry VIII’s sister who died in infancy; Cecily Burbage, Elizabeth’s wet nurse; Mary Howard, widowed but influential at court; Elizabeth Boleyn, mother of a controversial queen; and Elizabeth Barton, a peasant girl who would be lauded as a prophetess. Their stories are interwoven with studies of topics ranging from Tudor toys to contraception to witchcraft, painting a portrait of the lives of queens and serving maids, nuns and harlots, widows and chaperones.

The Lives of Tudor Women available now from Book Depository Amazon US and Amazon UK

Elizabeth Norton is a British historian, specialising in the queens of England and Tudor period. She is the author of the bestselling The Temptation of Elizabeth Tudor (Head of Zeus/Pegasus, 2015), as well as biographies of four of Henry VIII’s six wives and England’s Queens: The Biography (Amberley, 2010). She has a double first class degree from the University of Cambridge and a masters degree from the University of Oxford’.

Follow Elizabeth on her Website, Twitter and Facebook