The Bayeux Tapestry Museum

The Bayeux Tapestry is perhaps the most famous of ancient comic strips. It depicts events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England, 1064-1066, culminating in the Battle Of Hastings, and the struggles between William Duke of Normandy, (later William the Conqueror) and Harold Godwinson, Harold II of England, after the death of Edward the Confessor, in some 50 images, with captions or titles in Latin.

While referred to as a tapestry, The Bayeux Tapestry is, in fact, an embroidery. It is dyed wool yarn embroidered on linen. It is also often assumed the tapestry originated in Bayeux. Its importance as an historical artifact was rediscovered by scholars in 1729, where it was displayed annually in Bayeux Cathedral, in Normandy, Northern France. The earliest reference to the tapestry occurs in the records of the cathedral, in a 1476 inventory.

The origins of the tapestry are the subject of much debate. Traditional French legend has it that was made by William The Conqueror’s wife, Queen Mathilda, and her ladies-in-waiting. In France it is sometimes referred to as La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde. However, recent scholarship has concluded that it was commissioned by William’s half-brother, Bishop Odo, who after the conquest was made Earl of Kent, and often sat as Regent when William was away in Normandy. Bishop Odo built Bayeux Cathedral in the 1070s, it was dedicated in 1077, so it seems likely the tapestry was commissioned to be displayed in the cathedral to honour William, but as Odo’s power-base was Kent, and some of the Latin of the titles apparently displays some Anglo-Saxon accents, and Anglo-Saxon needlework was renowned at the time, it is probable that it originated in Kent, made by Anglo-Saxon seamsters. There are many other theories, even a suggestion by Andrew Bridgeford, in 1066: The Hidden History Of The Bayeux Tapestry, that it was designed and made in England and the images given secret meanings to insult and undermine Norman rule.

With its bright colours, intricate embroidery, incredible size, it is a truly remarkable historical artifact. The accuracy of the history it depicts is again, subject to much debate. It has been commonly assumed that King Harold died at Hastings with an arrow in his eye. However, there is evidence that the arrow was a later addition to the tapestry, added during a repair, that there may have been a lance in that part of the picture prior to the arrow. One of the conventions of the strip form of depiction is that the same character is not shown twice in the same frame, another that someone dying is shown falling or lying. So there is some debate as to whether the two figures in the scene both represent Harold. Another medieval convention held that an injury to the eye indicated an oathbreaker or perjurer. The arrow in the eye could have been purely symbolic. Thus the entire tapestry is written in a language of symbolic gestures the meanings of which many are lost to us today.

It has been listed by UNESCO as one of the Memories Of The World, a register of the world’s most significant historical documents, and is now kept in the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux, in the Old Grand Seminary in the centre of Bayeux, France.

The Bayeux Tapestry Museum displays the entire length of the tapestry in a long gallery. It also features displays on the making of the tapestry, and the history surrounding it, has educational rooms for study and school groups, with quarter sized replicas of the tapestry to allow for close study and examination.

It is centered in the beautiful town of Bayeux, with pleasant walks, parks and gardens, and the historic Cathedral close by.

The Belgian Comic Strip Museum

To many people Belgium is most famous for chocolates. There is a Musée du Chocolat in the ancient town of Bruges, and Belgian chocolates are known throughout the world. Bordering France, Germany, the Netherlands and tiny Luxembourg, and a mere step away from England across the channel, it has always been the crossroads of Europe, a center of trade and communication, with three official languages, French, German and Dutch, further divided into numerous dialects of Flemish Dutch and Belgian French and Flemish German and countless other world languages spoken. It’s not surprising that the visual means of storytelling, the universality of the comic strip, has been perhaps Belgium’s other most famous export.

The Adventures Of Tintin, the story of the world travelling, mystery solving young reporter, by Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi (who wrote under the name Hergé) first appeared in 1929 as a comic strip in the children’s supplement to the Belgian newspaper Le XXe Siècle, was later serialized in Belgium’s leading newspaper Soir, continued in its own Tintin magazine (René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo, creators of Asterix, had their first big success with Oumpah-pah, which appeared in Tintin magazine) and became the series of 24 comic albums we know today with the creation of Studio Hergé in 1950.

The Smurfs (in French Les Schtroumpfs), were created by Belgian cartoonist Pierre Culliford (who wrote under the name Peyo) in 1958. A Schtroumpf first appeared in Peyo’s earlier comic, Johan et Pirlouit, the story of a brave young page and his sidekick in medieval times, who met the small, blue skinned, magical gnome like characters in the story the The Flute with Six Holes. The name developed purely by chance. While dining with fellow cartoonist André Franquin, Culliford forgot the French word for salt, and asked Franquin to pass the Schtroumpf, (pronounced somewhat like the German word for sock Strumpf). They spent the weekend bantering back and forth with the nonsense word, their wordplay, the use of the world Schtroumpf as a substitute for other words, was a feature that carried on with The Smurfs. The Les Schtroumpfs characters became popular and soon had their own series. Later in Dutch translations Schtroumpfs, became Smurfs, and the name Smurfs was adopted in the English version. One could perhaps speculate that the Smurfs floppy hats derived from the German meaning of their original name. Another suggestion is that their hats are Phrygian caps, worn by the people of the Anatolian region during Roman times, which became known as Liberty caps (you will see them depicted in art from the French and American Revolutionary periods), probably through a confusion with the Pileus, the felt cap worn by freed Roman slaves. However, it seems much more likely the hats are simply somewhat mushroomish camouflage for the small, gnomish creatures.

The Belgian Comic Strip Museum not only celebrates the Franco-Belgian tradition, of which Tintin, The Smurfs, and Goscinny and Uderzo’s The Adventures Of Asterix are the best known internationally. It explores the comic strip art in all its variety, from children’s fables and adventure stories, American superheroes and underground comix, sci-fi strips and graphic novels of the 70s and 80s. Asterix first appeared in the Franco-Belgian Pilote magazine, who also published American underground legend Robert Crumb, and French high SF & Fantasy artist, Philippe Druillet, perhaps most familiar in magazines like Heavy Metal. It has permanent exhibits on the Franco-Belgian tradition, the wider History and Art of the comic strip, a look at the incredible Art Nouveau building designed by Victor Horta in which the centre is housed. Recent temporary exhibits include a look at the work of American innovator Wil Eisner, creator of The Spirit, who coined the term graphic novel to describe his later explorations of urban life in books like A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories, The Building, Dropsie Avenue, and others.

The Museum is also one of the first to use Google’s Open Gallery platform, which can be used to create online archives and virtual exhibitions. You can view their Open Gallery exhibition here.

The Belgian Comic Strip Centre also has a library, study rooms, a gallery, conducts conservation work and offers activities and guided tours.

The Belgian Comic Strip Center – Museum is located in the magnificent Waucquez Warehouse, designed by Victor Horta for textile baron Charles Waucquez and opened in 1906, at 20 Rue des Sables, Brussels.

The Cartoon Art Museum

In 1987 Charles M Schulz, creator of Peanuts, made an endowment to a group of comic book and cartoon art enthusiasts in San Francisco. In the preceding few years the group had been organizing exhibitions with artwork from their own collections, a museum without walls, celebrating cartoon art in all its diversity that proved to be hugely popular. With the endowment the museum established premises in San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Gardens cultural district.

Since that time The Cartoon Art Museum has held over 100 exhibitions and produced 20 publications exploring the diversity of cartoon art in magazines, animation, comics, graphic novels, underground zines, and book illustration.

Past exhibitions have looked at 100 Years Of Chuck Jones, La Raza Comica – The Latino-American in the Comic Arts, 60 Years Of MAD Magazine, they champion a great many small press and independent works, as well as covering the giants of the field, with celebrations of Superman’s 75th anniversary, the art of Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, and the Art Of DreamWorks Puss In Boots.

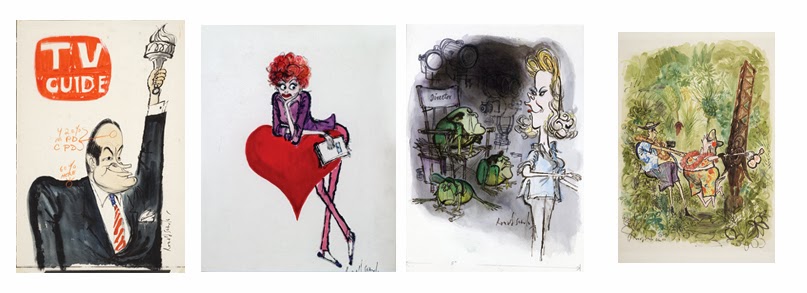

Currently they are running exhibitions on English cartoonist Ronald Searle; titled Searle in America, creator of St Trinian’s and other bitingly humorous satirical cartoons. Searle was working in the US in the 60s, producing cartoons for the leading magazines of the day Life, Holiday, Look and others, applying his wry wit to American politics, the Kennedy v Nixon campaign, the characters and casinos of Las Vegas, even drawing on the set of popular TV shows like Bewitched and F-Troop. Animator Matt Jones, curator of the exhibition, and host of the Ronald Searle Tribute website, has gathered a collection of rare and extraordinary Searle material, much of it unseen since first publication in the late 50s and early 60s.

Also showing until March 16, 2014 is Grains Of Sand: 25 Years Of The Sandman, a retrospective looking at Neil Gaiman’s extraordinary saga, one of the most critically acclaimed series of all time, that was published in monthly issues from 1989 to 1996 by DC Comics/Vertigo.

And last but not least Sam and Max – Swift and Mirthful Justice: The Art of Steve Purcell looks at the often kooky noir adventures of the canine and lapine detectives. The fedora wearing dog and rabbit-ish investigators Sam & Max have tangled with all sorts of ludicrous criminal elements and absurd paranormal monsters in Purcell’s fantastical version of New York City. They’ve appeared in comics, computer games, TV series and an Eisner Award winning webcomic. If you haven’t seen Sam and Max, you have missed a delightful absurdist adventure.

The Cartoon Art Museum is located at 655 Mission St, San Francisco, California. It holds over 6,000 pieces of original cartoon and animation art, a comprehensive research library, and five galleries of exhibition space. They host a range of events including book signings, lectures, cartooning classes and workshops, and exhibitions.