This week’s venue will need little introduction as it is not only one of the most iconic buildings in England, but also arguably the most beautiful.

Canterbury Cathedral was founded in 597 by Augustine who duly became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. The original cathedral was destroyed by fire in 1067, just a year after the Norman invasion. Rebuilding took place under the auspices of the first Norman archbishop, Lanfranc, in 1070 and the new cathedral was finished in 1077. Subsequent alterations, improvements and necessary repairs due to fire damage, meant that the second Canterbury Cathedral was not fully restored until 1184.

Further extensions, repairs and modifications continued to be made over the centuries and still continue to the present day, with a constant need for conservation and preservation works now being of paramount importance in order to maintain the cathedral’s condition and protect it from the ravages of time and modern-day pollution.

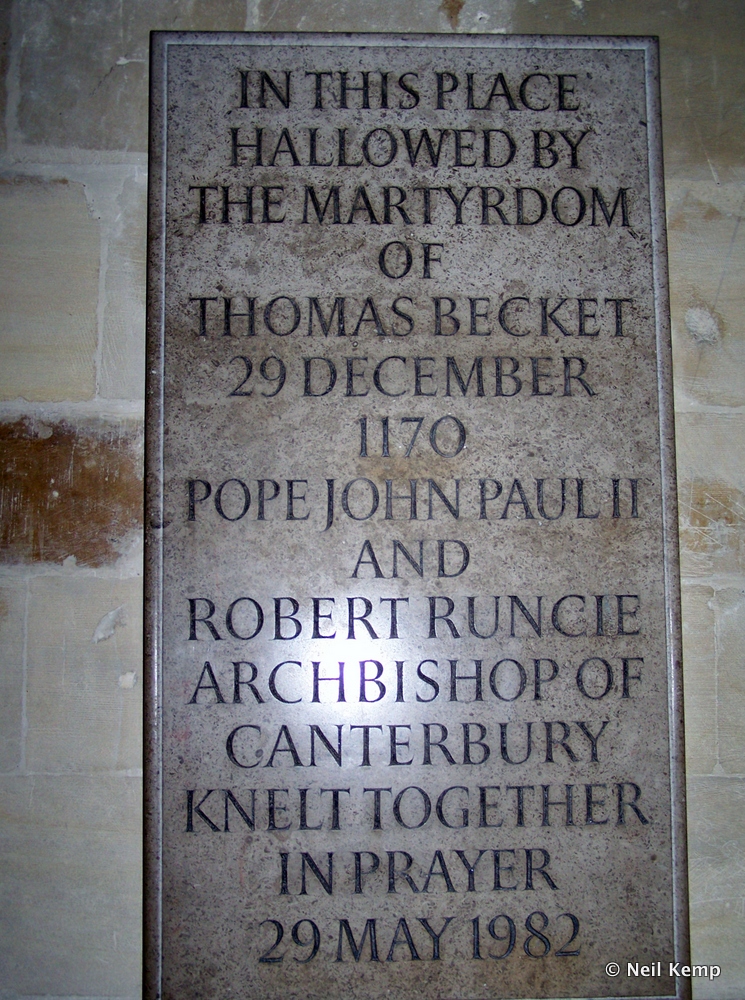

One of the most infamous episodes in English history took place in the cathedral on the 29th December, 1170, when the archbishop, Thomas Becket, was murdered by four knights, who mistakenly believed they were carrying out the wishes of the king, Henry II. The subsequent veneration of Becket made the cathedral a place of pilgrimage, this brought in much wealth, but also the need for expansion.

One of the most infamous episodes in English history took place in the cathedral on the 29th December, 1170, when the archbishop, Thomas Becket, was murdered by four knights, who mistakenly believed they were carrying out the wishes of the king, Henry II. The subsequent veneration of Becket made the cathedral a place of pilgrimage, this brought in much wealth, but also the need for expansion.

From 1180 until 1184 the present Trinity Chapel was constructed, being designed to house the shrine of St Thomas Becket, and a further extension was also added to house relics of Becket, which was said to include the top of his skull, struck off during his murder.

Although both the chapel and extension were completed by 1184, Becket’s remains were not moved from his tomb in the crypt until 1220.

Becket’s shrine was placed immediately above his original resting place in the crypt and consisted of a marble plinth raised on columns, atop of this Becket’s remains were placed in an iron box and contained inside a wooden chest, which was then laid over with gold. Other treasures were added to the chest over the years, including jewels sent as offerings by sovereign princes, whilst many other valuables were placed nearby. The chest was kept covered most of the time, but this cover was raised when a sufficient number of pilgrims had gathered, allowing them to gaze with awe at the bejewelled container of Becket’s mortal remains.

Much income was derived from the many pilgrims who made their way to Becket’s shrine, believing it to be a place of healing and their journeys were later immortalised in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

In 1538 Becket’s shrine was removed by order of Henry VIII and the cathedral itself ceased to be an abbey shortly afterwards, during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, which was also implemented by the royal command of Henry VIII. Whilst the destruction of Becket’s tomb almost appears to be an act of unnecessary spite on Henry’s part, it probably had as much to do with his venal desires, as the confiscated treasures of the shrine needed two full coffers and 26 carts in order to be carried away.

More wanton acts of vandalism took place under Puritanical rule, which included the smashing of many of the cathedral’s stained glass windows. Repairs started immediately upon the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, but took until 1704 to be completed.

Today Becket’s shrine is marked by a single candle, close by another significant interment in the Trinity Chapel, that of Edward Plantagenet, perhaps better known as The Black Prince.

The last major alterations to the cathedral occurred in 1834, when the original Norman northwest tower had to be demolished due to structural concerns. This was replaced with a perpendicular style tower in keeping with the southwest tower, which effectively now made them twin towers.

For many years there was no charge to enter either the cathedral or its precincts, however the modern world has somewhat forced its way into this spiritual institution and now any visitor to the cathedral must pay. Whilst appreciating the needs of the cathedral, I did find the sum of £9.50 rather steep, but having said that, the average tourist from afar (perhaps we should call them modern-day pilgrims) would consider the price cheap and well spent in order to view this iconic landmark of English history. Canterbury as a whole is totally geared up to the tourist industry, indeed it has no other, and the prices charged across many venues would make many a local blink in disbelief. So, do the visitors to Canterbury Cathedral get value for their money? It is a question that is unanswerable in reality, as it will be a very individual experience to anybody that enters this magnificent building. Indeed, it may appear somewhat unseemly to even pose the question, but it would seem that the cathedral, like most of the retail outlets in Canterbury itself, have now concluded that the average tourist has plenty of spare cash and the pursuit of that cash now seems paramount.

Upon entering the cathedral one is immediately met with an information desk in the form of a bookstall, keen to sell you a general guide to the cathedral. A helpful tool or an opportunity to make money? The many donation boxes that used to be in evidence when entry to the cathedral cost nothing still remain in situ, obviously for those that believe they haven’t yet paid enough in order to enter this building. The final clincher comes upon leaving. You duly follow the exit signs, which also indicate the cathedral gift shop. It is only when you reach the end of your destination that you realise that you actually have to exit through the gift shop. How many people will walk straight through without making a purchase, I wonder? In fairness, I must add that a fundraising appeal was set up in 2006 in order to raise the eye-watering sum of 50 million pounds with which to protect and enhance Canterbury Cathedral’s future as a religious, heritage and cultural centre. That is going to take an awful lot of gift sales, entrance fees and donations and as such the new commercialism of Canterbury Cathedral can perhaps be forgiven.

My big question is; why isn’t more state and lottery funding being used to protect one of Britain’s best known landmarks? It seems that the goodwill of the public is once again being used to fund schemes that should surely be the prerogative of heritage funding in some form.

Having made my way into the cathedral purely to view its contents and beauty, one immediately comes across the perpendicular style nave. It is marvellous in its simplicity and yet awesome to view, as one instinctively looks upwards to the magnificent ceiling of the nave. Advancing through the nave and up to the next level you enter the Trinity Chapel, and the rather gloomy lighting only seems to make the viewing of the candle marking Becket’s shrine even more poignant.

Having made my way into the cathedral purely to view its contents and beauty, one immediately comes across the perpendicular style nave. It is marvellous in its simplicity and yet awesome to view, as one instinctively looks upwards to the magnificent ceiling of the nave. Advancing through the nave and up to the next level you enter the Trinity Chapel, and the rather gloomy lighting only seems to make the viewing of the candle marking Becket’s shrine even more poignant.

The crypt is, as you would expect, even darker and exudes an air of reverence and respect which every visitor unquestioningly adheres to. Contained at one end of the crypt is a military chapel, and it was rather thought-provoking to see the tattered remnants of many regimental colours and to think of the sacrifices made by so many over the years in order that I, and the many others around me, could choose what to do and when to do it in complete freedom. Above this level, but below the level of the nave, are the cloisters and one can imagine the thousands of footsteps that have walked those stones before.

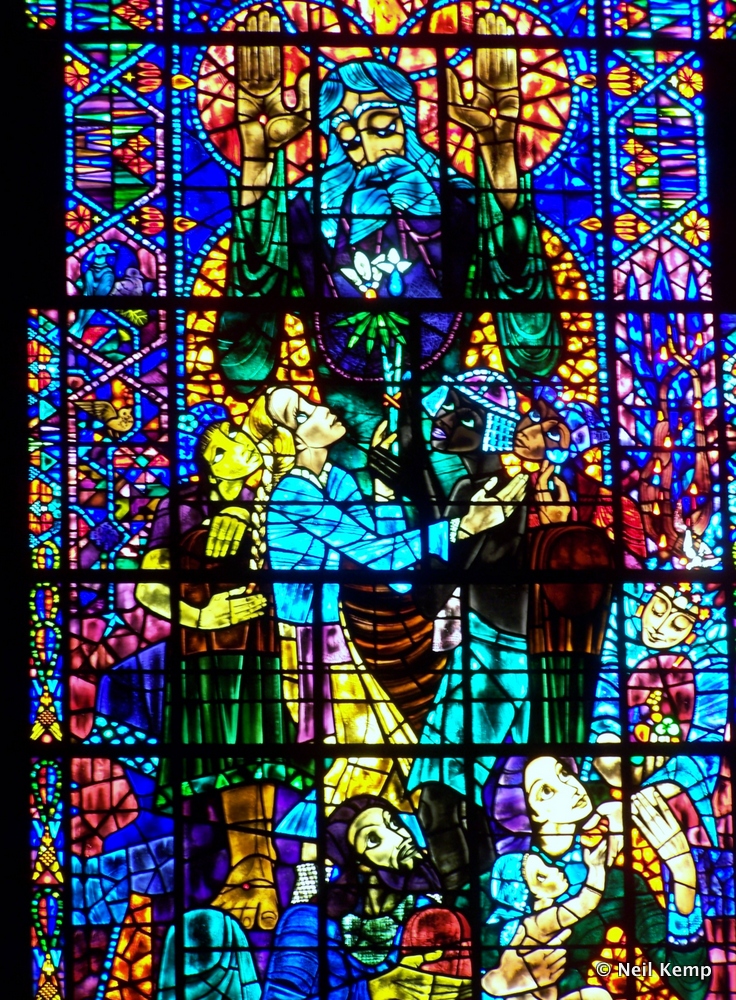

The stained glass windows are, of course, magnificent, but many are constantly under repair through necessity and thus the tourist will be forever marginally disappointed.

The external as well as the internal structure of Canterbury Cathedral is a wonder to behold, but it does take a surprisingly short time to see most of what there is to see, inside and out. I had remembered Canterbury Cathedral to be so much more, but then our memories of the past often deceive. It is what it is, a building to worship in and house the dead. It is, of course, so much more in spiritual, educational and historic terms, but to view in the here and now, one mustn’t expect too much. The main beauty of the cathedral is the building itself, not what is housed inside, and if one remembers that then you will probably consider your £9.50 well spent.

As I departed through the gift shop, I mused that it would be a wonderful experience to sit in such a magnificent building and listen to the choir in full voice. An experience such as that would be truly priceless, even to an old cynic such as me.

Making my way along Canterbury’s narrow, medieval streets, close to the old city wall that still stands impressively guarding the cathedral’s precincts, I thought of the epitaph that marked the tomb of The Black Prince:

Such as thou art, sometime was I.

Such as I am, such shalt thou be.

I thought little on th’our of Death

So long as I enjoyed breath.

But now a wretched captive am I,

Deep in the ground, lo here I lie.

My beauty great, is all quite gone,

My flesh is wasted to the bone.

Suddenly, even the pre-Christmas commercialism that seemed to exude from every business didn’t appear out-of-place, and it seemed churlish and venal to count the cost of visiting such a marvellous building.

It is worth remembering that life is good, but sometimes it takes a perspective on death to make us realise this universal truth.

Neil Kemp is a keen and passionate amateur historian and prize winning photographer who lives in Margate, on the North Kent coast in the United Kingdom. Before retiring he worked both with and at Margate Museum, overseeing budgets on a number of historical projects.