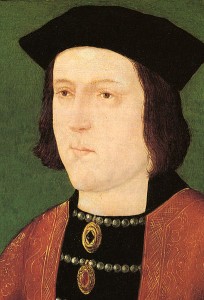

The secret marriage between a Duchess and a Squire may have raised a few eyebrows in 1437, but no one was expecting Jacquetta and Richard Woodville to become members of the most powerful family in England. A long happy marriage, and fourteen children later, their world was turned upside-down when their eldest daughter Elizabeth made her own secret marriage. The King of England, Edward IV, had fallen in love and married an impoverished widow, Elizabeth Woodville.

The secret marriage between a Duchess and a Squire may have raised a few eyebrows in 1437, but no one was expecting Jacquetta and Richard Woodville to become members of the most powerful family in England. A long happy marriage, and fourteen children later, their world was turned upside-down when their eldest daughter Elizabeth made her own secret marriage. The King of England, Edward IV, had fallen in love and married an impoverished widow, Elizabeth Woodville.

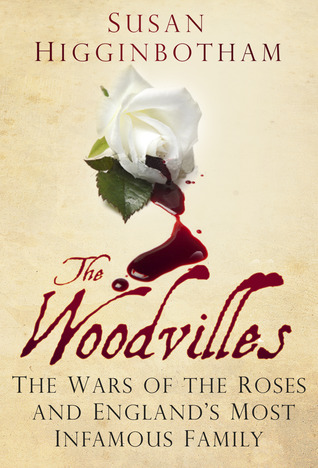

Branded as social upstarts, greedy, grasping and manipulative, the Woodvilles have been denigrated for centuries. Fortune may have taken them to the throne of England, but years of war and the betrayal of their brother-in-law would destroy them. Susan Higginbotham joins us to discuss her new book, a study of the real Woodvilles, the family behind the myth.

Why did you decide to research the Woodvilles as a family?

Back when I was writing my first novel, I began to read historical fiction a great deal, and as the Wars of the Roses had intrigued me for some time, I naturally began to read a lot of novels set during this time period. The Woodvilles were almost always negatively depicted there. I began to ask myself, “Were they really so bad?” and that led me to began doing my own research.

The Woodvilles were quite a large family, did you find it difficult to research any particular family members?

Except for Katherine, Elizabeth Woodville’s sisters are a historical blank—we know genealogical information about them, but very little else. That wasn’t a surprise, of course, given the fact that women’s lives of this period generally aren’t as well documented as men’s. I would have liked to have found out more about Richard Woodville, the third Earl Rivers, the least known of Elizabeth’s brothers, but he lived life well out of the spotlight, it seems.

Why is it that the Woodville family has managed to be so maligned over the centuries?

I think there are several reasons. One reason, I think, is pure snobbery, the sense that the Woodvilles were getting rather above themselves. Another is the existence of stories such as that involving the ruin of Sir Thomas Cook and the execution of the Earl of Desmond, which until relatively recently were accepted without being subjected to scrutiny. Another reason is the influence that historical fiction has had on popular culture. Novels set in this period published in the past few decades have been overwhelmingly sympathetic to Richard III, and since fiction lends itself to portrayals of people as heroes or villains, the Woodvilles, as the forces aligned against Richard, have come naturally to fill the role as villains.

Jacquetta’s second marriage was for love, to a man far below her social status. Did her secret marriage to Richard Woodville cause much scandal at the English court? They seemed to be back in favour quickly enough.

It doesn’t seem to have made much of an impression at the English court, probably because Jacquetta, who had not borne John, Duke of Bedford, any children during their short marriage, was of no dynastic importance to the English after his death. Had she given Bedford a son, who would have therefore been in the royal succession, the reaction might well have been stronger.

There is evidence of animosity between Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick and the Rivers well before Edward IV married Elizabeth Woodville. You described how he dragged them from their beds in the middle of the night to publicly humiliate them, what was the cause of the enmity between them?

At that point, the enmity was factional—Richard Woodville, Lord Rivers (Elizabeth’s father) had remained loyal to Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou. Warwick at this time was in Calais, the captaincy of which had been given to Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, who was attempting to dislodge Warwick from the town. Rivers was in the process of gathering a fleet to come to his aid when he and his son Anthony were taken in a surprise attack and hauled to Calais—sooner, as one chronicler wrote with delightful snideness, than they had planned on arriving there.

Jacquetta appears to have been close to Queen Margaret of Anjou, and Jacquetta and Richard had a prominent position at the Lancaster court. How difficult do you think it was for them to have to swear fealty to a new king?

I imagine it was very difficult. But they had a large family, many of whom were still young children, to consider, so pragmatism had to overcome sentiment. It was a choice a lot of people made after the devastating battle of Towton.

The second secret marriage in the Woodville family is a rather more famous one. You stated the common people had no problem Elizabeth Woodville as their new queen, despite her less lofty heritage, how did the marriage affect both Edward and Elizabeth’s relationship with their nobles?

Warwick’s relationship with Edward, of course, was damaged by the king’s marriage, and by the marriages of her family members that followed, such as that of the young and wealthy Duke of Buckingham to Katherine Woodville instead of to one of Warwick’s own daughters. But the Crowland Chronicler, for one, thought that it was differences over foreign policy that was the chief cause of the men’s estrangement. I think there would have been friction even if Edward had made a conventional marriage to a foreign princess, simply because Edward, who had come to the throne in 1461 when he was not quite 19, was maturing and becoming more of his own man.

There were many advantageous marriages arranged for members of Elizabeth Woodville’s family after she married the king, this has given her the reputation of being “grasping” and “manipulative” and somehow Edward seems to have had no say at all. How accurate is this assumption?

She certainly used her position to the advantage of her family—but she was hardly unique in this. Part of the problem was that unlike a foreign queen whose relations remained overseas, Elizabeth had plenty of family in England to help up the ladder. But she was more restrained than she’s often given credit for. No marriages were arranged for her brothers Richard and Edward or for her son Richard Grey, and their landed gains were fairly modest as well.

I find it very unlikely that Edward was manipulated by Elizabeth. He replaced Anthony Woodville as governor of Calais with Lord Hastings, to Anthony’s chagrin, so he clearly was able to act against the wishes of the family when it suited him.

On that note many historians make a great deal of Elizabeth being a social climber and a commoner, how much of that is taken from contemporary evidence? Would you say historians have managed to blacken her name as much as, and if not more, than her contemporaries did?

There’s no doubt that the disparity in Edward’s and Elizabeth’s social positions shocked contemporaries—there’s plenty of evidence to that effect. At least the couple’s marriage did Henry VIII the service of paving the way for his own controversial marriage to Anne Boleyn!

To answer your second question, I can do no better than to cite an excellent article by A. J. Pollard, “Elizabeth Woodville and Her Historians.” Pollard notes that two historical traditions have grown up around Elizabeth Woodville: one of the femme fatale, the other of the mater dolorosa—both “male constructs of types of women.” It’s the femme fatale—the manipulative woman using her sexual hold over Edward to bend her to his will—that has held sway over the past few decades, despite the dubious evidence for it.

On the other hand, more recently, historians like Anne Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs have done a great service in re-evaluating Elizabeth, but as Pollard points out, after 500 years of Elizabeth’s being pushed into one mould or to the other, it’s a challenge to find the real woman.

After the Earl of Warwick had executed Jacquetta’s husband and son, he then tried to accuse her of witchcraft. Why do you think he used that particular charge?

Assuming that the evidence against Jacquetta—the images that she allegedly made—was manufactured, I think he used the witchcraft charge in 1469 because such charges had been effective in the past against high-ranking women—Joan of Navarre, Henry IV’s queen, and Jacquetta’s own sister-in-law from her first marriage, Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester. And Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth was so out of the ordinary that a plausible case could be made that Jacquetta had used witchcraft to bring it about, although we don’t know whether this played into the charges brought in 1469. The possibility that Jacquetta was dabbling in magic can’t be ruled out, of course, but it should be remembered that the accusations, which Jacquetta vigorously denied, came at a very politically expedient time, and the case against her crumbled once Edward IV got free of Warwick.

This is a good time to point out that despite the association of Jacquetta’s family, the house of Luxembourg, with the legend of Melusine the water-witch, there’s no evidence that Jacquetta took more than an ordinary interest in the story. She owned a manuscript of the tale, part of a collection of various texts, but it was a popular work that could be found in the libraries of other ladies as well.

Elizabeth Woodville had to seek sanctuary several times during the tumultuous years of war during her marriage. The public seemed to support Elizabeth Woodville whenever she was under threat, does this not say something about her character, that she was able to hold the love of her subjects after so many years?

I wouldn’t say that she was loved by her subjects—her daughter Elizabeth of York was far more popular–but she certainly had admirers, such as the Crowland Chronicler, who described her as a “most benevolent queen,” and she was in many ways an exemplary royal consort, bearing children regularly, performing good works, and interceding with the king. Even in the turmoil of 1483, she and her family had their allies, and the belief that her sons had been murdered by Richard III sparked a rebellion and ultimately would bring an obscure exile, Henry Tudor, to the throne.

Elizabeth Woodville suffered a great deal of tragedy during her life, we could assume she was relieved after Richard III was defeated and her daughter became the next Queen Consort of England. However Henry Tudor didn’t seem to want her to rest on her laurels. How do you think she may have felt about Henry trying to arrange her marriage to the King of Scots?

I wish I knew! Given the enmity between the English and the Scots, it would likely have been a daunting prospect.

The Woodville men don’t seem to get as much attention as the women in the family. They had prominent military and court careers, did you come across anything in your research that stood out to you?

I hadn’t realized before I researched my book what an active part Anthony Woodville played in defending London in 1471 against the Bastard of Fauconberg. After the high drama of Barnet and Tewkesbury, this battle gets overlooked, as does Anthony’s role in it. I also was delighted to find a contemporary description of his father’s role at Towton.

So out of a family of strong women and talented military officers, which Woodville would you want by your side in battle?

Probably Edward Woodville. As his conduct in Brittany shows, he would fight until the last gasp.

Visit Susan at History Refreshed and find out more about her books at susanhigginbotham.com.

Visit Susan at History Refreshed and find out more about her books at susanhigginbotham.com.

I am the author of two historical novels set in fourteenth-century England: The Traitor’s Wife: A Novel of the Reign of Edward II and Hugh and Bess. Both were reissued in 2009 by Sourcebooks.

My third novel, The Stolen Crown, is set during the Wars of the Roses. It features Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, and his wife, Katherine Woodville, as narrators. My fourth novel, The Queen of Last Hopes, features Margaret of Anjou, queen to Henry VI, and is set mainly in the earlier years of the Wars of the Roses. It was released in January 2011. My fifth novel’s, Her Highness, the Traitor, heroines are Jane Dudley, Duchess of Northumberland, and Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, who respectively were the mother-in-law and the mother of Lady Jane Grey.

Buy The Woodvilles by Susan Higginbotham.

Buy The Woodvilles by Susan Higginbotham.

From an acclaimed historical fiction author comes the first nonfiction book on the notorious and perennially popular Woodville family, investigating such controversial issues as the fate of the Princes in the Tower and witchcraft allegations against Elizabeth and her mother. In 1464, the most eligible bachelor in England, Edward IV, stunned the nation by revealing his secret marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, a beautiful, impoverished widow whose father and brother Edward himself had once ridiculed as upstarts. Edward’s controversial match brought his queen’s large family to court and into the thick of the Wars of the Roses. This is the story of the family whose fates would be inextricably intertwined with the fall of the Plantagenets and the rise of the Tudors: Richard, the squire whose marriage to a duchess would one day cost him his head; Jacquetta, mother to the queen and accused witch; Elizabeth, the commoner whose royal destiny would cost her three of her sons; Anthony, the scholar and jouster who was one of Richard III’s first victims; and Edward, whose military exploits would win him the admiration of Ferdinand and Isabella. This history includes little-known material such as private letters and wills.