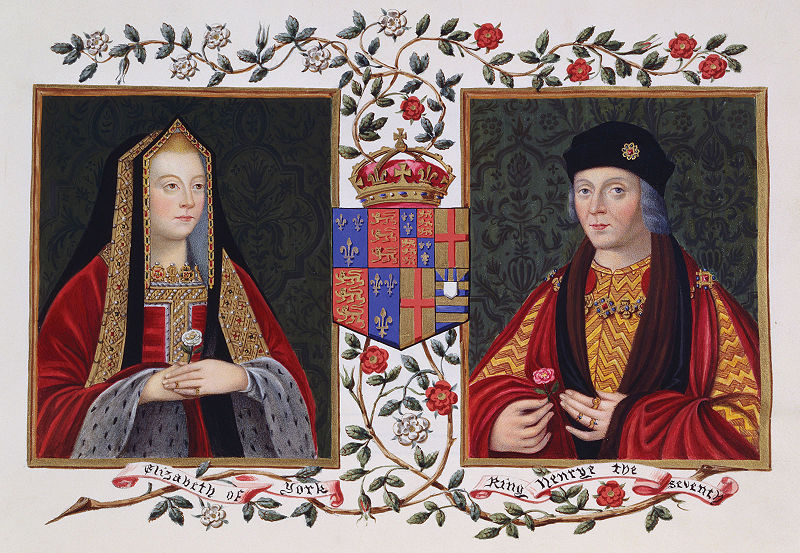

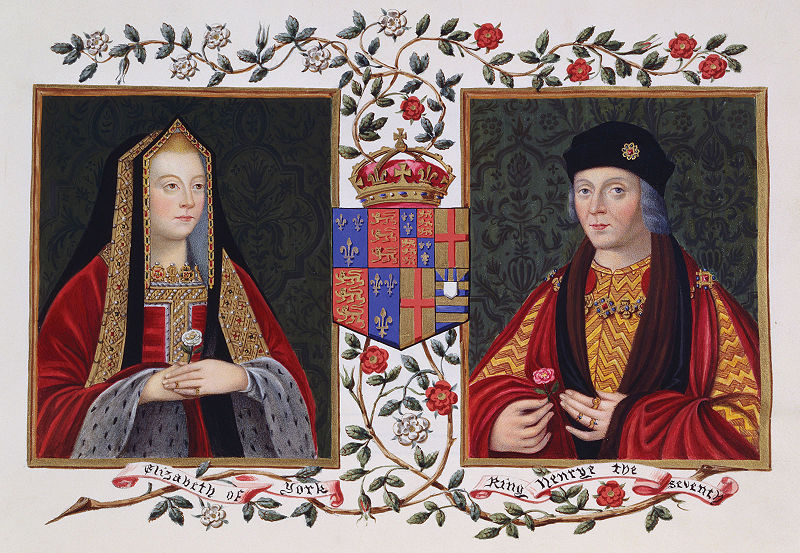

Elizabeth of York was the product of a love match. Her parents King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville had a long and happy marriage and Princess Elizabeth would be raised in a loving environment with many siblings. Her own marriage was a dynastic one. Her betrothal to Henry Tudor was arranged by their mothers during their suffering under King Richard III. The marriage would unite the houses of Lancaster and York, ending decades of war. It was a successful marriage, the most successful in the Tudor dynasty, and by all contemporary accounts Henry and Elizabeth had a close relationship. Yet historians have continued to perpetuate the myth that Elizabeth of York was subjugated by her husband and her mother-in-law, deprived of wealth and power.

Elizabeth of York was the product of a love match. Her parents King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville had a long and happy marriage and Princess Elizabeth would be raised in a loving environment with many siblings. Her own marriage was a dynastic one. Her betrothal to Henry Tudor was arranged by their mothers during their suffering under King Richard III. The marriage would unite the houses of Lancaster and York, ending decades of war. It was a successful marriage, the most successful in the Tudor dynasty, and by all contemporary accounts Henry and Elizabeth had a close relationship. Yet historians have continued to perpetuate the myth that Elizabeth of York was subjugated by her husband and her mother-in-law, deprived of wealth and power.

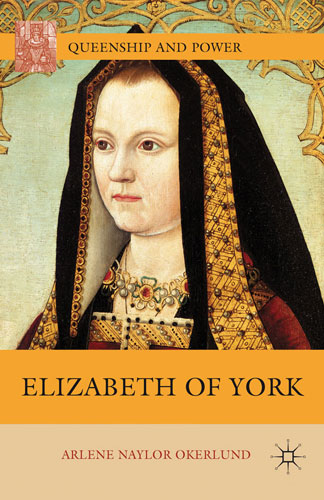

Professor Arlene Okerlund joins us to discuss the truth about the marriage of Elizabeth of York and Henry VII.

You have written books on both Elizabeth of York and her mother, Elizabeth Woodville. Elizabeth of York has always been seen as one of the most beloved Queens of England, and her mother one of the most notorious, why do you think the opinions of both women are so disparate?

Much of the answer lies in historiography. As the title to my biography of Elizabeth Wydeville indicates, she was a queen consort slandered in her time by political enemies, especially Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. His political screed against the “covetous, seditious” Wydevilles formed the basis for the Wydeville reputation that lasted into our own century. Similarly, when Richard III seized the throne in 1483, political propaganda accused the Wydevilles of being “low born” (a charge easily refuted by looking up the lineage of Elizabeth’s father Richard Wydeville, Lord Rivers, and her mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, in the Complete Peerage). Such claims hardly differ from modern negative political attacks that specialize in character assassination. What initially intrigued me was the fact that some subsequent historians–even until today–accepted such propaganda as truth without evaluating its source, its context, or the perspective of its perpetrator.

Elizabeth Wydeville had political enemies, but she also had supporters during her lifetime. To cite just a few examples: during the readeption of Henry VI, a London butcher provided half a beef and two muttons each week to sustain her household even though she was no longer queen. After Edward IV regained the crown, the Speaker of Parliament praised the Queen for her conduct during his exile. During Richard III’s coup, the Abbot of Westminster Abbey protected Elizabeth and her five daughters at considerable risk to himself. Unfortunately, historians have tended to accentuate the negative reports, rather than the positive. Sometimes they deliberately distorted the record: claims of her “greedy, grasping” character, for instance, partially originated in the Thomas Cook affair, where she was blamed for demanding “queen’s gold,” even though the Great Chronicle clearly states that she forgave the fine.

Her daughter Elizabeth of York, on the other hand, escaped direct political attacks during her lifetime. She was a child during the rebellion of Warwick, too young to feature in the negative propaganda against Edward IV and her mother. Further, marriage to the princess Elizabeth could add credibility to any claimant’s quest for the throne, a good reason not to besmirch her reputation. Although Richard III and his Parliament did declare her to be illegitimate (a general indictment that applied to all of Edward’s children), the king then invited Elizabeth to join his Court where rumors of their marriage became so rife that he had to deny them in a public meeting. A bit of inconsistency in Richard’s actions, but an indication of the position that Elizabeth, the princess, enjoyed.

When Henry VII married Elizabeth and united the houses of York and Lancaster, the people of England looked to that union as a means of ending decades of war. The queen’s gracious, cultured personality won the affection of her subjects, contributed to Henry’s success as king, and added to her popularity. Elizabeth of York was a rare queen who received mostly good publicity during her lifetime, a factor reflected in her subsequent reputation.

How do you think the many tragic events in the young Elizabeth’s life helped shape her as a queen?

Life early taught Elizabeth that she had to cope with events over which she had no control. At age 3, her holiday in Norwich was interrupted by Warwick’s capture of Edward IV—changing dramatically the child’s luxurious, royal life to one of “scant state.” A year later, Elizabeth and her two sisters (ages 3 and 1) found themselves living in the even more straightened confines of Sanctuary, where her mother gave birth to Prince Edward.

Further, her father used her as a pawn in his political games. Twice, she was betrothed: at age four to George Neville (Edward IV’s peace offering to Warwick) and at age nine to the Dauphin of France. Jilted at age 16 (when Louis XI cut a better deal with Maximilian), the princess was left bereft when Edward IV unexpectedly died.

Emotional turmoil during the summer of 1483 added to Elizabeth’s lessons in life: once again living in Sanctuary, she saw her two brothers disappear into the Tower (never to be seen again), learned of the executions of her uncle Anthony Wydeville and her half-brother Sir Richard Grey, and suffered Parliament’s declaration that she was a “Bastard.”

The mature Elizabeth of York emerged from a childhood where she learned to survive overwhelming tragedies. Those lessons helped her prevail during the decade of rebellions against Henry’s reign–and later when coping with the death of her son Arthur.

Although the marriage between Henry VII and Elizabeth of York famously united the houses of Lancaster and York, do you think that the constant rebellions in the name of York throughout their marriage may have placed a strain on their relationship at times?

It is dangerous to speculate about strains in marital relationships—especially from a distance of five centuries and vastly changed expectations of the marriage contract. Too frequently such speculation merely projects our own attitudes and expectations on to others.

As my answer to the preceding question indicates, Elizabeth’s entire life was afflicted by uncertainty and threats, both personal and political. The decade of rebellions against Henry merely continued a pattern with which she was well acquainted. I will only observe that all evidence of the life Elizabeth shared with Henry indicates an unusually close, loving, and happy relationship.

A common tradition surrounding Elizabeth of York is that she was subjugated by her husband and mother-in-law. Your book goes a long way towards dispelling many of the myths surrounding Elizabeth of York, how has this perception of her evolved?

Perception derives from observed actions, which are interpreted by the observer and often promulgated as general truths. The Spanish ambassador reported, for instance, that Elizabeth did “not like” the influence that his mother wielded over the king—evidence of Elizabeth’s subjugation. But the ambassador also described collaborative efforts by the queen and her mother-in-law, which indicate a positive and cooperative, rather than a hierarchical relationship. Unfortunately, the ambassador’s negative report established the general perception, while the more positive facts were ignored. Historians, again, have perpetuated such perceptions.

Similarly, Henry’s “delay” in marrying Elizabeth and in scheduling her coronation has led to claims that he was not treating his queen with the respect and honor she deserved. When I analyzed the timeline of events and the factors pertinent to both their marriage and Elizabeth’s coronation, however, reasons for each schedule became clear and compelling.

Too often, selected and incomplete details form the basis of perception. All evidence must be evaluated before a conclusion can be drawn, which is what I attempted in my biography of Elizabeth of York. I also quote at some length from contemporary documents (to the displeasure of some critics), allowing readers to evaluate for themselves the evidence leading to my conclusions.

Your exhaustive study of Henry VII’s privy purse accounts show us that he was not the miser he is made out to be when it came to spending on his family, and he spent a fortune on Elizabeth of York’s wardrobe. Where does the myth of mended gowns and tin buckles on her shoes come from?

Actually, Elizabeth’s tailors did mend her gowns (all velvet, incidentally). Such thrift is not a sign of penury or miserliness, but a sensible means of preserving elaborate gowns carefully crafted from expensive fabrics. If the myth implies that Elizabeth lacked the appropriate dress and accoutrements for a queen of England, a quick review of her “Privy Purse Expenses” (available free on-line via Google books) will dispel that misunderstanding.

Queens had an income and household independent of their husbands and were expected to manage this themselves. Elizabeth did seem to struggle with money earlier in her reign and Henry VII kept adding to her dower over the course of her life to try and supplement her income. Why do you think she struggled with her finances early on in her reign?

Based on what we know about Elizabeth’s finances, she always struggled with insufficient funds. Her Privy Purse expenses for the last year of her life indicate that vendors were only partially paid and that the queen had borrowed money from lenders. When she died, the queen’s plate was pledged for a loan of £500 to pay her attendants. Part of the problem derived from Elizabeth’s generosity—she freely gave tips to attendants and subjects, alms to the poor, donations to shrines, and gifts to religious devotees. She supported her sisters, lent money to the king, and bought jewels and gowns for herself. Elizabeth of York simply spent more than she received as income.

Early in Henry’s reign, the problem was different, more systemic: the king had to develop a financial model that would support the kingdom, as well as the household of himself and his queen. His first Parliament restored the dower of Queen Dowager Elizabeth Wydeville, an act politically essential to re-establish her royal position and the regal heritage of her daughter. Those lands and their income, however, constituted the traditional source of funds for the queen’s household, depriving Elizabeth of York of that support. Not until early in 1487 did Henry transfer the queen’s traditional dower to his wife (creating much historical speculation about why he was “punishing” the Queen Dowager). Because Elizabeth of York lived with Henry much of the time, an independent income for her household became less urgent.

You’ve shown us that Elizabeth and Henry did not like to be parted; they frequently travelled together and had a close relationship with no hint of scandal throughout their long marriage. They also had their younger children close at hand. Do you think that their past experiences may have helped forge a bond between them and that they worked together towards a stable dynasty and happy family life?

Elizabeth of York grew up surrounded by family—sisters, brothers, aunts, uncles, cousins. In the midst of rebellions and tragedies, her mother, Elizabeth Wydeville, always kept her children close, nurturing and supervising their care.

Henry Tudor, on the other hand, lost his father before birth, hardly knew his mother, and became a ward of William, Lord Herbert, at age five. He spent his childhood at Raglan Castle in the midst of the Herbert family where he was well educated, but seldom visited by his mother. At age 14, he was forced to flee to Brittany, where he and his uncle Jasper spent 14 years in exile separated from family and country, effectively under house arrest.

The backgrounds of Elizabeth and Henry could hardly be more different, making psychological explanations of the bond they forged—and a bond it certainly was—difficult. They did, however, share the experience of political uncertainty that precluded any sense of personal security. Perhaps they sought that security in each other. Certainly the scribe’s report of their response to Arthur’s death reveals the intensity of their bond and their shared love.

Do you think Elizabeth of York was integral to the success of the Tudor dynasty?

Elizabeth of York contributed enormously to Henry’s success. The union of Lancaster and York promised an end to decades of war, economic uncertainty, and domestic chaos—all of which were fervently sought by a tired, dispirited nation. The presence of Elizabeth by Henry’s side symbolized a new peace, a message Henry visibly and symbolically advertised throughout England with the red-and-white Tudor rose, which fast became the icon of his dynasty.

Equally important, Elizabeth’s calm, quiet demeanor steadied both her husband and the nation through continuing rebellions and crises. Her generosity, her love for the arts, her cultured presence sent a quiet message that transcended civil conflict and family feuds. Elizabeth’s subjects loved her and called her “the gracious queen.” At her death, she was mourned by the entire nation. No one, however, wept more than her husband, Henry VII.

Arlene Okerlund has written Elizabeth Wydeville: The Slandered Queen, published by The History Press, and Elizabeth of York published by Palgrave Macmillan.

Arlene Okerlund has written Elizabeth Wydeville: The Slandered Queen, published by The History Press, and Elizabeth of York published by Palgrave Macmillan.

Visit Arlene at San Jose State University.

Arlene Okerlund, Professor Emerita of English, retired after a career of teaching Renaissance literature at San José State University in California. After several years in the classroom, she served six years as Dean, College of Humanities and the Arts, and seven years as Academic Vice President before returning to her first loves of teaching and research. The author of scholarly articles on Shakespeare, Spenser, Marlowe, Donne, and Dryden, Professor Okerlund also writes for popular audiences, including the newsletter of the Peninsula Banjo Band with which she plays tenor banjo.

Currently, she teaches at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at Santa Clara University and lectures at The Institute for the Study of Western Civilization in California.

Buy Elizabeth of York by Arlene Okerlund

Buy Elizabeth of York by Arlene Okerlund

This book tells the story of the queen whose marriage to King Henry VII ended England’s Wars of the Roses and inaugurated the 118-year Tudor dynasty. Best known as the mother of Henry VIII and grandmother of Elizabeth I, this Queen Elizabeth contributed far beyond the act of giving birth to future monarchs. Her marriage to Henry VII unified the feuding houses of Lancaster and York, and her popularity with the people helped her husband survive rebellions that plagued his first decade of rule. Queen Elizabeth’s gracious manners and large family created a warm, convivial Court marked by a rather exceptional fondness between the royal couple. Her love for music, literature, and architecture also helped inspire England’s Renaissance.